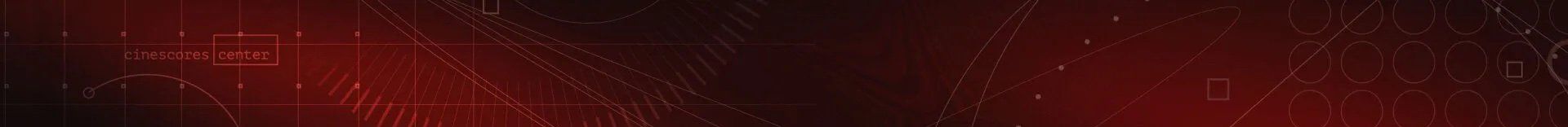

David Raksin 1912-2004 / under the patronage of the Raksin estate

David Raksin's is a complicated personality. It has more facets than even the circular point of view of a Picasso could concentrate into a single portrait. On the one hand Raksin is a wit, a wag, a wisecracker. He delights in puns, aphorisms, and anecdotes in which he himself is the central character. Humor gives way to indignation and sarcasm when he talks about critics who find fault with his music. For such detractors of his art, like the one who summed up the score for FOREVER AMBER with the adjective "loud," he invents verbal Schrechlichkeits of vivid and sometimes obscene imagery. Famous indeed are his lunch-table jeremiads, with which he invokes divine wrath upon evildoers in the film industry, in domestic politics, and in the councils of nations. At times he abandons himself to Hamlet's somber moods, or he will play, in his imagination, the role of a Manfred or a Job. Although he is suspected of enjoying these moods more than he ought, he is ever ready to be de-livered from them by a fine concert, a s

Before the age of talking pictures, continuous music played by large orchestras, theater organs, or pianos accompanied the so-called silent films. It is thus possible to view the advent of the synchronous sound track as marking the beginning of an era in which movie music has become increasingly subordinate to dialogue and sound effects. To be sure, the end of the musical silent era was not universally applauded, even by non musicians. D. W. Griffith, for example, was unwilling or unable to adapt his cinematic technique to sound films, believing that only music - and he had strong ideas, for better or for worse, about what was appropriate - should accompany his celluloid dramas. And there were others, besides those unhappy actors and actresses who could not perform speaking parts, who approached (or retreated from) the possibilities of sound with distrust or hostility. Among the skeptics were two comedians, Charlie Chaplin, who continued to give music the leading voice in his pictures (e.g., MODERN TIMES), an

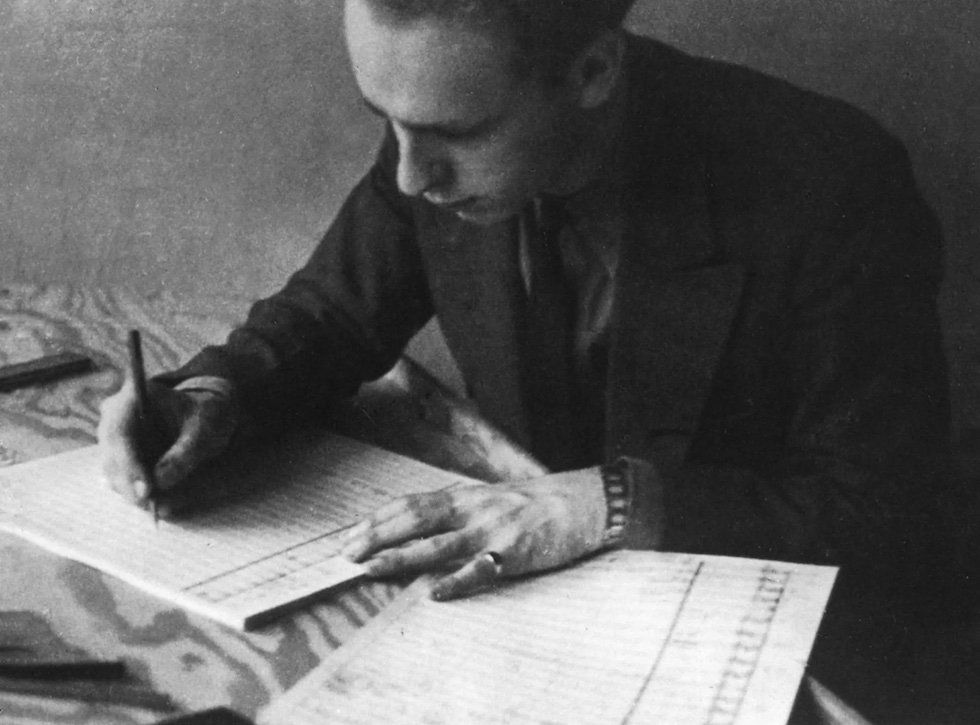

The new adventure began on August 8, 1935, four days after my twenty-third birthday, with a telegram from Eddie Powell, addressed to me “care Harms Inc.” in New York City. Since I was in Boston, arranging and orchestrating music for AT HOME ABROAD, a show that was in its pre-Broadway tryout, the people at Harms forwarded the wire to me.

One of the most respected of all American film composers - both for his music and his celebrated wit - Raksin began his long and distinguished movie career in 1935, when he came to Hollywood to assist Charlie Chaplin with the music of MODERN TIMES. He composed music for more than 100 films, including LAURA (1944), whose theme became one of the most-recorded songs in history with more than 400 different versions.

Radio program recordings

David Raksin, was writer and host of his own KUSC program in Los Angeles, The Subject is Film Music, in the 1970s. It included tribute shows to Korngold, Steiner, Newman… who were then gone, but had live hour interviews with those Raksin could round up including Rozsa, Fielding, Friedhofer, Kaper, Mancini, Bernstein etc. Raksin would introduce the show and the guest and then they would usually go over a chronology of the composer’s work, stopping occasionally to play a music cue illustrating the work in question. The music usually came from the limited LP soundtrack examples for each or, in some cases, Charles Gerhardt’s RCA series. The Hugo Friedhofer interview was produced by radio station KUSC around 1979 or 1980.

Behind the Screen

Some years ago, in the course of a lecture at the University of Southern California, I was trying to explain that empathy, or identification with the feelings of his characters, is an inner resource indispensable to a film composer. I suggested that talent for career in film composing might be partially assessed through a “Hecuba Test”. The reference was of course, to the soliloquy ("O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!”) in Act II of HAMLET wherein the Prince, his own feelings in deep bondage, marvels at the passion with which the First Player invests the contrived emotionality of a playwright. Says Hamlet:

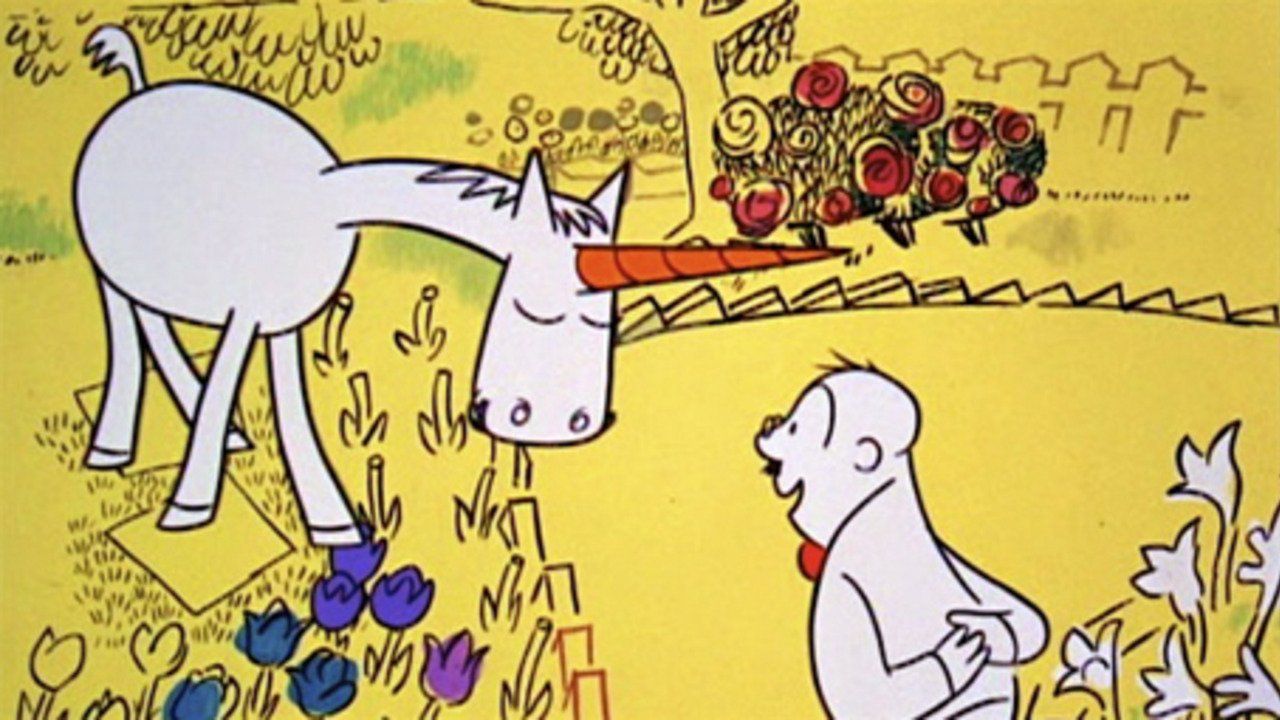

James Thurber’s modern fable The Unicorn in the Garden first appeared in the New Yorker on October 31, 1939. David Raksin composed a charming score for chamber orchestra and recorder for the 1953 United Productions of America film. The studio elected to recreate Thurber’s original illustration style. The Unicorn in the Garden has sparse dialogue, because Raksin tells the story with the sounds. Raksin’s score calls for a recorder to be the thematic voice for the silent unicorn. Members of the animation field voted The Unicorn in the Garden one of the fifty greatest cartoons of all time.

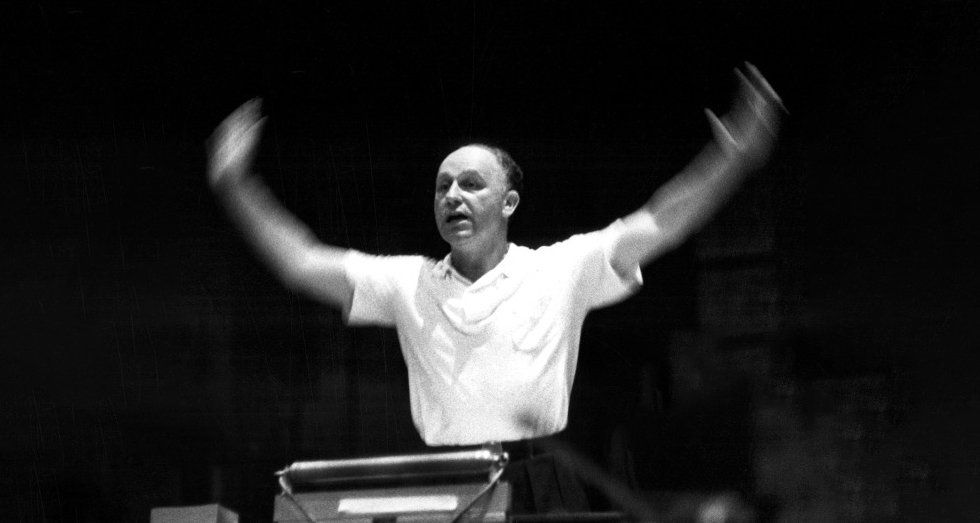

Raksin said he accepted the assignment because executive producer Stuart Millar was an old friend. Due to the usual TV complications involving last-minute changes, Raksin had just two and a half weeks to write 35 minutes of music for a 31-piece orchestra. “I worked literally 18 to 20 hours every day. Which is what we used to do all the time - because we had this stupid, prideful idea that we could absorb any amount of punishment and we could make up for ineptitudes in scheduling, which naturally don't take human endurance into consideration. So it was a hassle.” But, he was quick to add, “it's still fun to compose, to solve the problems of a movie like this.”

Interviews

At the age of 81, David Raksin appears to be a remarkably vital and busy man; he’s the president of The Society for the Preservation of Film Music and a teacher of film music theory and technique at USC. He took time off in October to come to Belgium as a guest of the International Film Festival in Ghent. This interview took place on Sunday morning, October 17, in a noisy hotel lobby. Of a quiet composure – he has seen and heard it all – but very outspoken in his views, he talked to us (Paul Van Hooff, Sybold Tonkens and I) about his career. Later on that same day I met him briefly outside the Festival Headquarters and he asked me about the architectural features of the town (Raksin also teaches urban ecology).

This interview is an edited version of a longer, formal oral history interview that forms part of the Oral History Collection at the Weill-Lenya Research Center. At the time of the interview, Peggy Sherry was Associate Archivist at the Research Center. She is now Reference Librarian/Archivist, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries.

Counterpunch

What is the function of music in moving pictures? What, you ask, are the particular problems involved in music for the screen? I can answer both questions briefly. And I must answer them bluntly. There are no musical problems in the film. And there is only one real function of film music – namely, to feed the composer! In all frankness I find it impossible to talk to film people about music because we have no common meeting ground; their primitive and childish concept of music is not my concept. They have the mistaken notion that music, in "helping" and "explaining" the cinematic shadow-play, could be regarded under artistic considerations. It cannot be.

I live in a land where deference towards one's elders is scarcely the rule; young people grow up to think in terms of a man's essential worth rather than his seniority. "Essential worth" is, of course, a fancy generalization. It is a variable, a term that permits too many subjective responses. Nevertheless, the essential worth of a man like Igor Stravinsky is hardly disputable – when he is writing music. In the role of critic, however, his greatness is questionable. His recent pronouncements make this abundantly clear.

Letters

Letter to the Editor, Sight And Sound - Sir. - Several months ago you were kind enough to appreciate in a review of RIGHT CROSS the brief music I composed for that film. I wonder if you have any idea how gratifying it is to find that one’s work in a small film has not gone unnoticed? What pleased me most, however, was that you identified me as the composer of the score of FORCE OF EVIL. I am so accustomed (perhaps I should say “inured’’) to being introduced as the composer of LAURA that it was a real thrill to find someone who remembers FORCE OF EVIL and the music I wrote for it. This is my favourite score, and the picture was, to me, a fine film, misunderstood here and mishandled by those who released and were to have exploited it.

As a man who long ago discovered that ASCAP is an anagram of ASPCA, and who is therefore against flogging of dead cats, I wish to point out that most anti-Hollywood generalizations will simply not hold water. It is quite disconcerting to find people who ordinarily shy away from generalizations leaping to embrace the obvious and tiresome canards about Hollywood.

Reviews

Does any other composer tell as many entertaining anecdotes about his music as David Raksin? How he came to write his famous LAURA melody is the stuff of legends. Add to this Raksin's humorous tale of first playing his theme to THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL on the piano for Andre Previn, who was clearly underwhelmed. (“It was confused and confusing,” Previn writes in his autobiography, 'No Minor Chords.' “The harmonies tumbled over one another, and the melody was a snake.”) Raksin was discouraged, but days later was able to finally record the theme with full orchestra on the MGM soundstage. Previn, who was nearby, overheard the music and rushed up to congratulate him on such a lovely work. When the rather irritated Raksin pointed out that Previn's reaction to his piano version had been quite opposite just a few days previous, Previn could only respond: “Well… the way you played it, who could tell?!”

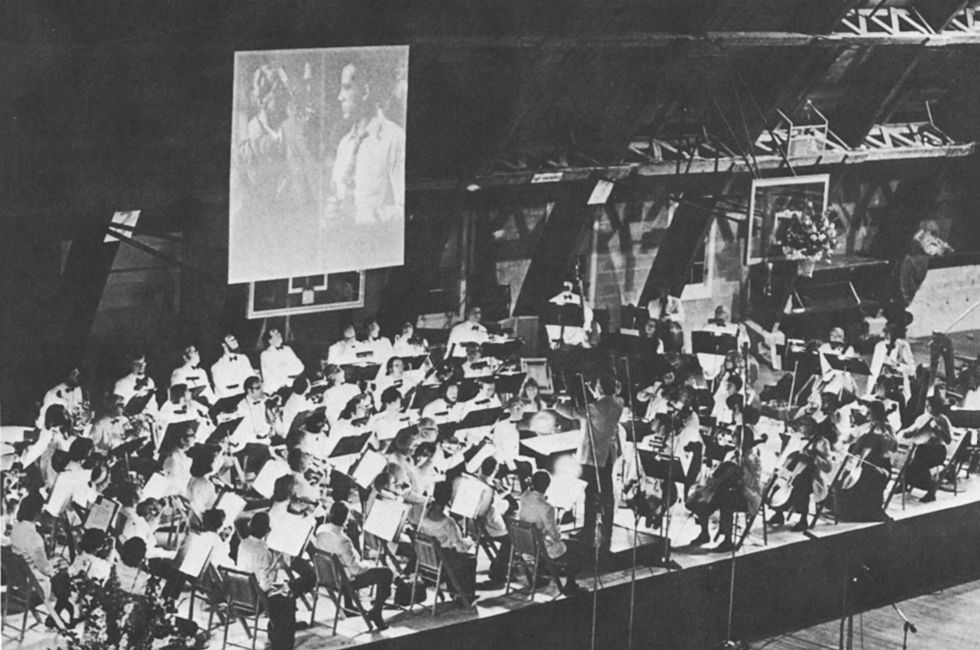

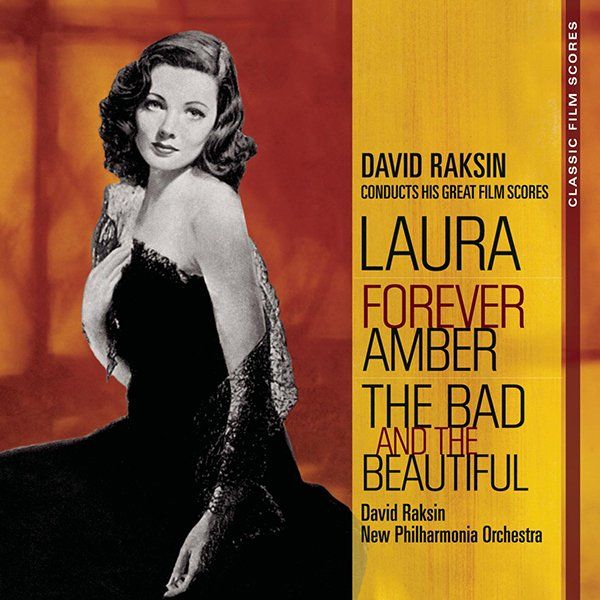

For myself, one of the highlights of the marvellous RCA Classic Film Score Series recorded back in the 1970s (and subsequently reissued in CD format) was GD81490 - David Raksin conducts his Great Film Scores: Laura; The Bad and the Beautiful and Forever Amber. That album was beautifully recorded and the playing of the New Philharmonia was first class. If you can find a copy of this CD grab it; it is crammed with memorable music - the haunting "Nocturne" from The Bad and the Beautiful, with its lovely clarinet solo, is worth the price of the CD alone - and Raksin's notes about his own music are revelatory particularly the poignant story about how he came to write his famous Laura theme. The Suite from Forever Amber, on the RCA disc is of 25 minutes duration and includes the very best from Raksin's score. Now, this new CD has nearly 65 minutes of music and every one of them is worth listening to - of how many (or rather how few) scores could you say that? I cannot pay this music a greater tribute.

Of all the albums in this great series, this has to be one of my favourites. The music is simply glorious. David Raksin’s film music album was one of the late entries in RCA’s 1970s Classic Film Score series - the original LP album was RCA Red Seal ARL1-1490. It was the only one not to have been recorded by Charles Gerhardt and the National Philharmonic Orchestra. David Raksin not only conducts his own scores but contributes the album notes. These essays are a fascinating and enlightening insight into the experiences of a composer working in Hollywood during its Golden Age. Raksin’s biographical details are also included as another erudite note by Christopher Palmer.

Two Weeks in Another Town (M-G-M, 1962) was a sort of sequel to The Bad and the Beautiful directed by Vincent Minelli for M-G-M in 1952. That celebrated film was Hollywood on Hollywood, the lid taken off seamier side of life there – the tack behind the glamour. The film gathered Oscars for screenwriter, Charles Schnee, Robert Surtee’s cinephotography, for its art direction, and for Gloria Graham’s supporting actress performance as Rosemary Barlow the unfaithful wife of writer James Lee Barlow played by Dick Powell. The star, Kirk Douglas, as Jonathan Shields (a role modelled on David O’ Selznick) was nominated for a Best Actor Oscar. The illustrious cast also starred Lana Turner as Georgia Lorrison (a role modelled on O’ Selznick’s wife and protégé, Jennifer Jones) and included Walter Pidgeon, Barry Sullivan and Gilbert Roland.