David Raksin: A Composer in Hollywood

Source: The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, Vol. 35, No. 3 (July 1978), pp. 142- 172

Published by: Library of Congress

With permission of the Library of Congress and the Raksin Estate

Before the age of talking pictures, continuous music played by large orchestras, theater organs, or pianos accompanied the so-called silent films. It is thus possible to view the advent of the synchronous sound track as marking the beginning of an era in which movie music has become increasingly subordinate to dialogue and sound effects. To be sure, the end of the musical silent era was not universally applauded, even by non musicians. D. W. Griffith, for example, was unwilling or unable to adapt his cinematic technique to sound films, believing that only music - and he had strong ideas, for better or for worse, about what was appropriate - should accompany his celluloid dramas. And there were others, besides those unhappy actors and actresses who could not perform speaking parts, who approached (or retreated from) the possibilities of sound with distrust or hostility. Among the skeptics were two comedians, Charlie Chaplin, who continued to give music the leading voice in his pictures (e.g., MODERN TIMES), and Stan Laurel, who did not have Chaplin’s musical sensibilities but made many classic two reelers that integrated sound with sight gags, thereby adapting successfully, if reluctantly, to the new genre.

In spite of a few early sound era experiments which omitted music entirely for the sake of realism - the popular 1929 version of THE VIRGINIAN with Gary Cooper comes to mind - sound films brought to Hollywood a kind of music making that is perhaps one of the most important and neglected phenomena in the history of American music. The quality of the music and its performance became film-making components for which the producers would have complete responsibility; and if they accepted this responsibility and worked well with their musicians, the dramatic timing of the scores could make a crucial contribution to the effectiveness of their films. That outstanding composers and performing artists were attracted to Hollywood indicates that the value of their contribution was appreciated, if not always well understood. Although some of their best work was discarded, mutilated, or wedded to films not equal to the quality of their scores, much of it was well used.

Therefore, it must be emphasized that our selections from David Raksin’s work, some of it cut from the final films for which it was written, were not made to demonstrate the insensitivity of film makers to good music. These examples from FORCE OF EVIL (1948), CARRIE (1952), SEPARATE TABLES (1958), and THE REDEEMER (1966) simply represent some of Raksin’s best pieces that are not available on records and which show how one of Hollywood’s best composers has solved, or attempted to solve, some of the problems of scoring films.

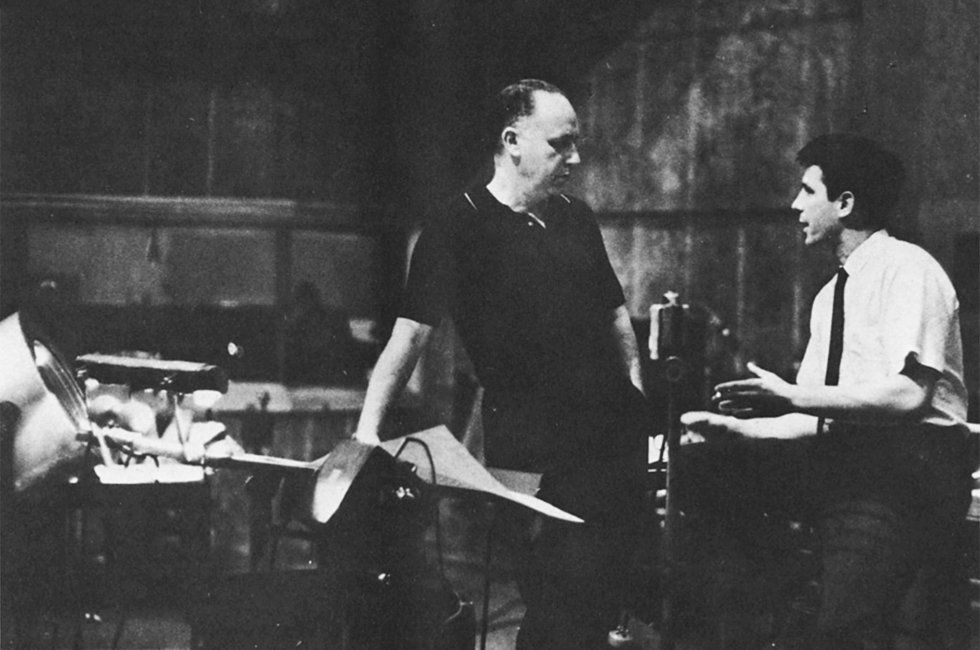

David Raksin’s score for the Otto Preminger film LAURA, released in 1944, launched both a remarkable song and its creator’s career as a recognized and sought-after composer. Raksin was already known in the music business as an outstanding professional, having worked in New York and Hollywood with Robert Russell Bennett, Alfred Newman, and Leopold Stokowski, among others. In Hollywood he had studied composition with Arnold Schoenberg and had done a variety of film work - from assisting Charlie Chaplin with the arrangements and orchestrations for MODERN TIMES to writing original motion-picture music. Always articulate and outspoken, his success with the film score and song “Laura” earned him a measure of respect that enabled him to work - and talk - as a composer in his own right. In spite of the fact that he has often had to maintain his integrity by taking stubbornly independent positions not calculated to ingratiate him with producers and directors, he has worked on more than one hundred films, including partial scores for some and the complete scores for about sixty features, and several hundred television programs - from dramatic series to documentaries.

Raksin neither preaches nor practices any theory of composing either pure or dramatic music. “I’m all too aware,” he has said, “that there’s hardly an idea or a concept in this world that doesn’t have an opposite pole which may be an equally viable alter native.”

As for those whose disdain for movie music precludes their having any theories about it at all (except that it must be bad), it is Raksin’s own music rather than his verbal eloquence - and he can be a virtuoso of the brutal epigram in defense of his art - which is the most effective response to their dismissing the validity of film music on the grounds that it is composed to order under pressure and restricted by the split-second timings imposed by visual, spoken, or other cues. While maintaining a high level of craftsmanship and applying the principle that film music must serve the picture’s dramatic purpose, Raksin has still been able to write music that can stand on its own. And, while the recorded excerpts which accompany this essay are intended to illustrate his dramatic ability, they can and should also be listened to for their intrinsic value as music, without reference to the films for which they were conceived.