David Raksin Remembers Kurt Weill

David Raksin working in his studio. Photo: Peggy Sherry

Originally printed in the Kurt Weill Newsletter, vol. 10, no. 2 (Fall 1992), pp. 6-9.

Copyright by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music. Posted with permission. © All rights reserved.

David Raksin Remembers Weill, Where Do We Go From Here?, and “Developing” Film Music in the 1940s

An Oral History Interview with Peggy Sherry

This interview is an edited version of a longer, formal oral history interview that forms part of the Oral History Collection at the Weill-Lenya Research Center. At the time of the interview, Peggy Sherry was Associate Archivist at the Research Center. She is now Reference Librarian/Archivist, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries.

2 October 1991. Ms. Sherry’ began by showing David Raksin the first few pages of the short score of the music for WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?, the 1945 Twentieth Century-Fox release with music by Weill and lyrics by Ira Gershwin.

Mr. Raksin, how did you come to work on WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Alfred Newman assigned me to this picture because Kurt had written the score with, as you say, lyrics by Ira Gershwin. The picture has an interesting sidelight in that originally they had intended to cast Danny Kaye as the lead, along with some very well-known comedian. But what happened, I guess, was that Zanuck and Goldwyn (the heads of competing studios) couldn’t agree on a loan of Danny. So they got Fred MacMurray in his place, who was really not all that bad. Fred MacMurray was very musical, you know. He played the saxophone. The picture was not particularly distinguished, which is a shame, because the music and lyrics were fun. I enjoyed working on it.

Part of Kurt Weill’s deal was that the underscoring [the back ground music to the action on screen] had to be based on his music, exclusively. No other composer’s music could be used. So Al Newman (who knew that I had grown up learning about musicals, which are really a very, very separate, and a fine art) assigned me to it. I notice on this score that I am credited with writing “Magic Smoke” and “The Genie.” This is slightly embarrassing for me. Of course I wrote them, but I had no idea I would ever get credited with them. I’m not even sure it’s legal. The whole picture should have been credited to Kurt, you know. Even what everybody else wrote. That’s not fair, but who am I to demand fairness? Who are they to be fair? Well, OK, I did write those bits and pieces. And, for copyright reasons, they all had to have names.

I went through the picture, writing the various sequences the way one does in underscoring - using Kurt’s material, rather than my own, except in these little things. We were in such a jam on this picture that you wouldn’t believe it, and I think Dave Buttolph was even brought in to do a reel or two. I don’t know how much he did, but I know that he did some, thank heavens. He was brilliant.

Do you know how Weill got hired to do the picture?

I haven’t the vaguest idea. I think Bill Perlberg wanted somebody to work with Ira, and, of course, Kurt and Ira had already done LADY IN THE DARK. Weill was something. He was a real marvel, you know, loved by everybody as a person. He was trusted by musicians, and musicians are not quick to admire other people.

So Weill had a reputation in Hollywood?

He had a reputation everywhere as a first-rate guy. Absolutely. And we did not know how first-rate he was. We knew that he was a marvelous song writer, that he was an adroit musician who knew how to develop stuff. It wasn’t until later that I realized he had studied with Busoni and had written a violin concerto and all these other marvelous pieces. In fact, very few people knew about any of it.

I remember that [the radio cantata]

Lindbergh's Flight was done here in Hollywood. We had a group that used to meet one night a week in an art gallery out on Sunset Strip. I still remember “Schlaf Charlie.” You know, Charlie Lindbergh is falling asleep, and then this sort of genie, or demon, or whatever it is, wants him to fold up; kind of encourages him to fall asleep, which is, of course, all wrong.

Who was in the group?

It was a group of artists, musicians, and writers. The head guru was a guy named John Davenport, who eventually, I think, became an editor of Life magazine. He was an English bird with the appropriate accent. One of his associates was Jerome Moross, the composer, and Jerry knew about Kurt Weill’s music. All I knew about him was, of course, the

Dreigroschenoper and

Mahagonny, stuff like that. Jerry Moross put me on to his music, so I got to know all those things, and I used to sing them all the time for people and loved them very much. Then I came across

Lindbergh's Flight. They did it here with just piano accompaniment and some wonderful guy singing the lead role. It was good. The text is by Bertolt Brecht, of course.

That’s correct.

Brecht. Not God’s gift to integrity and niceness. Oh, everybody knew about him. He was a very, very remarkable man, but he was also a drip. You know, he was a bounder.

You were a pretty young guy at the time that this movie was being made. Were you well acquainted with the world of composers at the studios?

Oh sure. Remember, I’d been out here since 1935. I came out to assist Chaplin on the music of MODERN TIMES, so I’d been out here about ten years by the time I went to work on WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

I gather it was kind of a rough world for a composer to find a niche.

Well, for me it wasn’t. I mean, I had my rough periods, but they were because I was construed as arrogant, which might even have been true. You see, people out here would call you arrogant if you would not automatically say yes every time a producer nodded. And I didn’t figure I was there for that reason. I was there to tell them what I thought as a musician. So there were times when I didn’t work. But, for the most part, everybody wanted me because I had started out with Chaplin.

I’d like to ask you some specific questions about this score. What part of the film-making process was it prepared for?

Oh, the score you have here is made after the film is totally finished. You don’t do the main title and all the underscoring until the picture is finished, or nearly finished. If you’re working on incomplete footage you’re going to have to do it over five times, and that’s just gruesome. There isn’t time or energy for that. Remember, this music is created under extreme duress. You get maybe four or five weeks to do something that should take three or four months

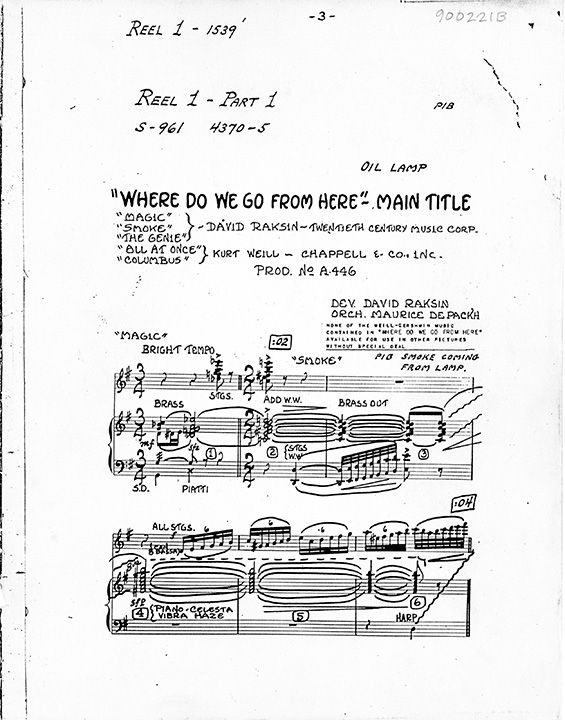

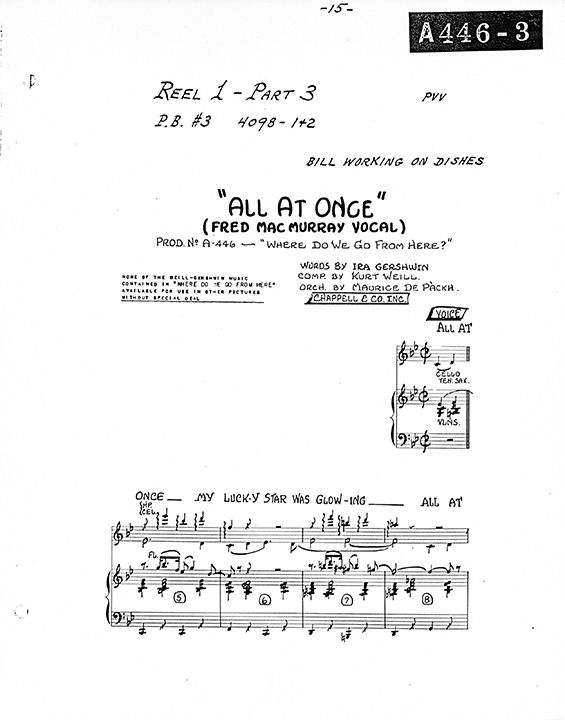

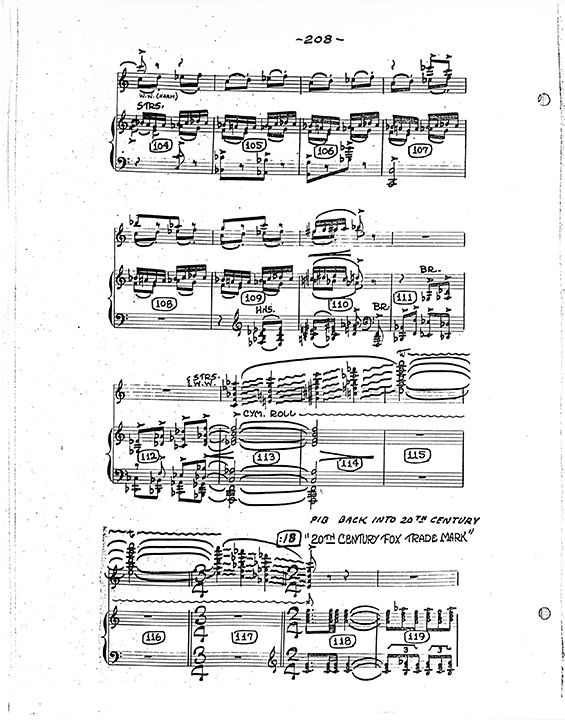

Pages from the short score of Where Do We Go From Here? Left to right: First page of the main title music, as developed by David Raksin; “All At Once,” as sung by Fred MacMurray; excerpt from the Finale, where Raksin introduced the Twentieth Century-Fox theme. Images provided by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music.

So, is this a conductor’s score?

This is what’s made from a conductor’s book. What it is, really, is a little Particell. It’s a reduction of the score. This one was probably done by a guy at Twentieth Century-Fox called Elton Kohler. He would manage, also under duress, to reduce all the stuff in the score down to a conductor’s book. There are a lot of places where it just says “brass.” It doesn’t say which brass, but that’s all there is.

Were there other scores?

Or is this, as far as you know, the only one that was left? Is this the only type of score that would have been preserved?

Well, of course, there were orchestral scores, made by Maurice de Packh from my sketches and made by various other guys like Eddie Powell - who probably orchestrated some of Kurt’s stuff - and Herbert Spencer. But, you know, there are conductor books all over the place. I have just a few, but they made them all the time.

So, when it says next to the title “Dev.,” what does that mean?

Devised, or developed. Let’s say you are starting with a composer’s thirty-two bar piece of music. There are times when you play the whole thirty-two bars. Other times you can’t do that because you have to adapt it to what the action is, and the action may call for all kinds of other stuff: stops and starts; changes and developments; doing the tune backwards, upside down, or whatever.

So you didn't work together with Weill.

No. I did not. I wish I had.

Since you did the developing for the underscoring, you worked on the music after he was finished with it?

Absolutely. He'd written all the music, and they gave it to me and said “go.” When you do development and devising, what you're doing is composing.

Can you explain to me the whole process, starting with the ideas in the composer's head and ending with the finished product of the film with the sound track?

Well, first, the composer gets assigned to the picture. He works with the producer and the director, maybe the script writer, and anybody else. (In this case, Weill probably would have worked with Darryl Zanuck, the head of the studio.) The composer and lyricist decide what they're going to do, where the music will be, and who's going to sing it. Then they work with guys from the music department, who will tell them the singing range and vocal capabilities of the cast, in this case Fred MacMurray. A pianist is assigned to MacMurray, and they try out the music to make sure it's OK for him. At that point, Ira and Kurt would have written any extra bars that are needed. (If there's going to be action, chances are they won't mess with that because they don't know how it's going to be cut, and it would be a waste of time to prepare music for any but the final version. They would leave that for a guy like me.) And then, when their songs are ready to go, they are recorded. Actually they're pre-recorded.

Do you know if Weill did any coaching during the pre-recording sessions?

I wouldn't think so. Usually, that came before. I can't remember who was under contract as a rehearsal pianist at the time, maybe it was Urban Thielmann. But let's say the rehearsal pianist taught MacMurray the song. Then Kurt and Ira would come in, and they'd sit with Ratoff and Bill Perlberg to listen to it, and Weill would have suggestions to make. If you're the composer, believe me, you have them.

What happens next?

The singer or actor goes on the stage and pre-records the song with Al Newman conducting, who is the best conductor we ever had here in town. Then they play that stuff back on the stage, and the actor lip-synchs while they film the whole thing. The picture is then put together, and they decide where they need underscoring. For that they talk to a guy like me.

And then you do the underscoring.

I do the underscoring…

With the development.

Yes, that’s right. Taking the material and developing it.

And stretching it out?

Yes, and cutting it down, dovetailing it, stuff like that. What you do is - if you’re really an honorable guy - you stick as much as you can to the composer’s music. In this case, as I said, it was possible until I got to the very end, where I had to diverge from that.

Sheet Music Cover and Kurt Weill in Hollywood in 1944, when Where Do We Go from Here? was being finalized by the studio.

Tell me about that. The divergence.

Well, at the very end of the picture, the hero - let’s say Fred - has been sentenced to death. And I think a guy who’s his rival for the affections of the girl is egging on the execution. Fred, at the last minute, manages to get away in a little cart - you know, drawn by a horse or a goat, or God only knows what. And he’s going like mad, while they’re pursuing him. And then ensues this chase through the centuries. You go to the sixteenth century, in which case he gets into a coach, drawn by several horses. Everybody’s costume changes. Then he goes into the seventeenth century, God only knows what he’s riding in there. Then the eighteenth century, then the nineteenth century, and finally, as he gets around to the twentieth century, he’s driving a Cadillac, or something like that. It makes kind of a tour and all of a sudden the screen says “Twentieth Century.” Well, there needed to be music for that. But after several days of working, I said to Al Newman. “I’m never going to be able to make this on Kurt's music. I can’t make the right kind of scherzi out of it. Sure, I can make anything fast, but it’s not going to work.” He said. “If you can't do it, I don’t think anybody else can either. So, why don’t you do whatever you want, and I’ll go in between you and the studio.” And so I did.

I remember the recording session; everybody was on the stage. I guess Grischa Ratoff must have been there, and Bill Perlberg. You know, it’s fun when you record. When we got to the last sequence of the chase (it’s done in pieces), all of a sudden “Twentieth Century” comes on, and you hear [he sings] the Twentieth Century-Fox signature, which Newman himself wrote. He nearly fell off the stand. I just thought it would be a funny thing to do, and it was. Everybody thought it was great, and Zanuck left it in. He would have thrown it out if he thought it was inappropriate. Anyhow, I did that bit, and all the rest of the finale. I was waiting to hear what Kurt would say, but I didn’t see him until maybe a year or so later.

Oh? Why not?

Well, he was already in New York, probably getting lessons in the method of living from Madame Weill. Anyway. I went to a concert down at the old Philharmonic Hall and, during intermission, I saw Kurt. I walked up to him, you know, figuring he’s not going to hit me on the head, although he might. He was with Maurice Abravanel, that wonderful old gent, that conductor. (They were very good friends, and I think somebody who was a buddy of theirs was conducting.) So I walked up to him, and he smiled, put his hand on my shoulder, shook my hand, and said “Very, very good.” I said, “What about the last sequence?” He just laughed: “I couldn't help wondering what in God’s name you were going to do with that, but it turned out very well.”

So after your contribution, what was left to be done?

Well, they did previews, and things like that, and they brought the picture back. Maybe they edited it a little bit. I mean, they wouldn’t think of leaving it alone so the music score wouldn’t get damaged, because I think in director’s and producer’s school they teach you, if you don’t mess around and louse up the score, you haven’t done your work.

How much control did you have over the editing?

Oh, I had no control over the editing whatsoever.

How about Weill?

He certainly could have expressed his opinion. And if he said, “Look, why did you cut out so and so? It’s important.” Perhaps he could have convinced them it was important to the story. But generally they didn’t really like it when we messed around with that.

And what about the success of the film?

I know very little about that. I’m sure that the snotty guys in New York looked down their noses at it. Sometimes the only way of knowing you’ve done the right thing is when they don’t like it. Because they’re really ignorant. If they weren’t ignorant, they’d be composers.

Whose idea was it to make this particular film into such a big musical film?

I haven’t any idea. Probably Bill Perlberg’s.

Did you know Weill personally? Did you see Weill often after that project?

No. I wish I had. I mean, I would have loved to. because he was such a charming, wonderful guy, and somebody I looked up to as well.

So, if you think about the other music of Weill that you know, how would you compare that with the music he wrote for WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Well, look, you’re asking the wrong guy, because I refuse to make a great differentiation among these things. If a man has the gift of being able to write in several different worlds of music, he is still the same man, and the same musical characteristics will appear there. Otherwise he’s a phony. You see? A guy like Aaron Copland writes things like

Rodeo, and then he writes the

Third Symphony, or the

Piano Fantasy. You cannot differentiate among those things. It’s ridiculous to do that.

You hear similarities, is that what you’re saying?

It’s not just that you hear similarities. You hear the man in them. The man remains constant. One time I was interviewing Aaron Copland, who was an old friend. I said to him, “Aaron, you know, it’s so odd. Here you are, a person who is universally loved, everybody in the profession loves you dearly, and yet, when I listen to your music, sometimes I hear all this implicit violence.” And he gave me one of those angelic smiles, and he said: “If it’s in the music, it’s in the man.” Same thing with Weill. His show music was the way it was because he was the man who studied with Busoni. You see, and he is the guy who wrote a violin concerto, and he is the guy who wrote

Lindbergh's Flight, To have that degree of sophistication and somehow do it so that it can be said in a simple way is marvelous, like one of those line drawings of Picasso.

So, suppose there are types and symbols and archetypes of Weill, the man, as you say, that are constant, and you wouldn’t necessarily say that there are themes or passages from his First or Second Symphony that show up in this film with Fred MacMurray?

I mean, it’s not as if one is being borrowed from the other? Yeah. The thing that remains consistent is the spirit of the composer. You’re going to hear certain things. Absolutely. Other guys tried to do them, you know, like Krenek, and, God forbid, Hanns Eisler. They would have died if they could have written a melody, a real melody, but never. Writing a tune is the scarcest thing in the world today. A real tune.