An Interview with David Raksin

Source: Soundtrack Magazine Vol.13 / No.49 /1994

Publisher: Luc Van de Ven

Copyright © 1994. Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

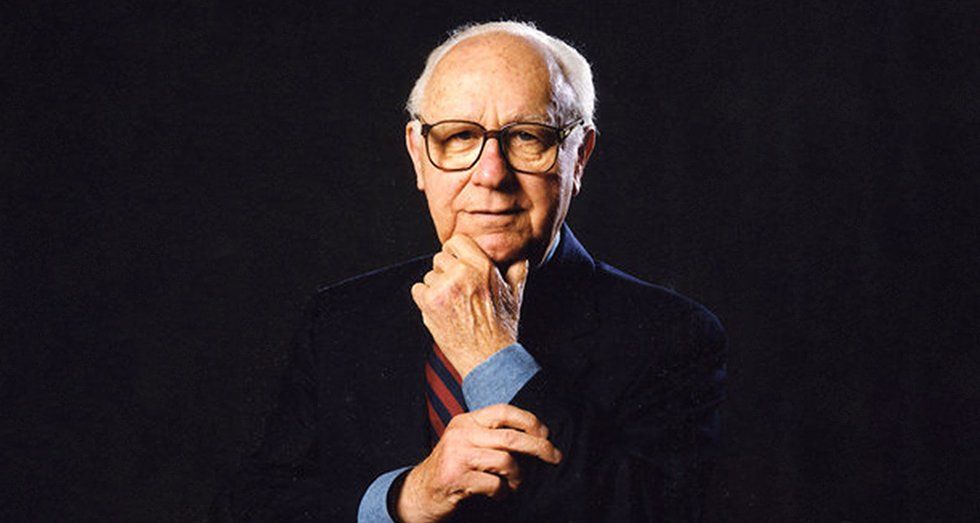

At the age of 81, David Raksin appears to be a remarkably vital and busy man; he’s the president of The Society for the Preservation of Film Music and a teacher of film music theory and technique at USC. He took time off in October to come to Belgium as a guest of the International Film Festival in Ghent. This interview took place on Sunday morning, October 17, in a noisy hotel lobby. Of a quiet composure – he has seen and heard it all – but very outspoken in his views, he talked to us (Paul Van Hooff, Sybold Tonkens and I) about his career. Later on that same day I met him briefly outside the Festival Headquarters and he asked me about the architectural features of the town (Raksin also teaches urban ecology).

Your first film work was for Charlie Chaplin on MODERN TIMES…

It happened because Charlie needed someone to work with him, because he didn’t know how to write music down and he also didn’t know how to develop material. He did have ideas. It’s not true that he didn’t have ideas; he just needed somebody to work with him. He always had people working with him on CITY LIGHTS, it was Arthur Johnston (Johnston wrote ‘Cocktail for Two’ and ‘Pennies from Heaven’) and on THE GREAT DICTATOR it was Meredith Wilson.

You were even fired…

Yes. That was about one week and a half after we had started working together. He was absolutely unable to cope with the idea that someone would dare to challenge him, differ with him. He was used to having absolute obedience. He was a total autocrat, everybody agreed with him and I didn’t. My idea was that I was there to be a musician, a composer and to make sure that the music was as good as it could be. He was appalled when I said: “Now Charlie, I think we can do better than that. Why don’t we change this…” and he fired me.

Alfred Newman got a look at the sketches I was making and he met me in a restaurant where I went with my friends Eddie Powell and Herbert Spencer (Eddie and I orchestrated MODERN TIMES). Al said to me: “I’ve been looking at your sketches and what you’re making of these little fragments and tunes is amazing. He would be crazy to fire you!” Al went to talk to Charlie; I got a call from Alf Reeves, a boss at Charlie’s studio and he told me to come back. I said I didn’t think so. “Don’t you like working at the studio?” he asked. “I love working with Charlie, but if I don’t have an understanding with him, the same thing will happen again. Unless I can do that I don’t want to come back.” So he arranged that and I made sure we were out of earshot, because if I had to say that to him in front of other people, I would have been challenging his authority. So we talked and I explained to him that if he wanted more stooges I wouldn’t want to be one of them and if he wanted a secretary he could buy one for nothing, but if he wanted somebody on the job 7 days a week in order to make sure the music was as first rate as possible, I would be glad to come back. So we started again and we worked together for more than 4 months.

The music was conducted by Alfred Newman…

Yes, he’s the best.

You worked a lot for Twentieth Century Fox in those days.

Yes, but later. I also worked for Al Newman when he was at United Artists and Goldwyn. Then I went to Europe to work on a show and when I came back I worked for Universal for a while, then I didn’t work for a while and eventually I went to Fox where I worked for a guy named Louis Silbers, who was head of the music department (he’s the guy who conducted Al Johson’s THE JAZZ SINGER and wrote a couple of famous songs). He was a journeyman musician and I didn’t like working for him, neither did anybody else. Eventually Al Newman came and took over at 20th Century Fox. He raised my salary considerably and I worked for him for several years. I left Fox in 1946 at which time my salary was $1,600 a week; which today would be equal to $7,000. Al couldn’t believe I was quitting, but I had to do it because otherwise Al and I would eventually never speak to each other again.

What was it like to work in a big studio with a big music department?

It was wonderful. There was a camaraderie that you would never believe. We worked together; we worked day and night, so we saw each other all the time. Some of us were such good friends we also saw each other outside the studio. There was a great respect for each other. I said many times that the most interesting thing about the profession is that we are friends. Johnny (Green) and André (Previn), we were all competitors, nevertheless we were friends. Because you admire the other guy’s work, that’s it! It is very nice to have people like that. In the 1930’s and early 40’s there was a group of us who used to meet at Eddie Powell’s house – he had some wonderful sound equipment – and we would play all the new records and sometimes we would have the scores and discuss them. It was great.

Were you also in touch with composers from the other film studios, such as Victor Young or Hugo Friedhofer?

Hugo and I were the closest of friends. Hugo orchestrated about one third of THE REDEEMER. He hadn’t been working and I was worried about him. Since I had orchestrated for him and he had orchestrated for me, I asked him. He said he had just been offered a film and I said he didn’t have to orchestrate for some guy if he could do his own picture. I tried to get several other guys to orchestrate for me, I tried Van Cleave, even my brother, but they were all busy and eventually I gave my sketches to the copyist and he copied the score from them.

You were not always credited in those days. What did you actually do, did you compose, did you orchestrate?

Mostly we never had time to orchestrate, but whenever possible I love to orchestrate. Composing is hard, orchestrating is fun. Some of those scores at Fox, we would come in on a Monday, look at a B-picture and on Thursday we’d record a score of 40-45 minutes. Buttolph, Mockridge and I used to write those scores in 3 days. We had very good orchestrators working for us, because there was no time to orchestrate. We made as good a sketch as we could, tell what instruments we required and we would come in on Thursday and record. They would never do that on an A-picture. An A-picture always had a single composer, but when AI Newman came in it was better, because he fought for us and we got up to 4 weeks.

You worked a lot with Mockridge and Buttolph, 2 underrated composers…

Mockridge was a very good composer, but David Buttolph was a marvel. They ought to release one of his scores, THE IMMORTAL SERGEANT. He was a much schooled composer, who studied composing and conducting in Germany. He was so good we used to have a joke about him, if Buttolph had a bad week he only did 3 pictures.

Some of your scores were conducted by Emil Newman…

Emil is listed as the conductor of LAURA, but actually it was conducted by his brother AI, because Emil was busy on some other pictures.

When you discussed the scores in those days, did you have to discuss things with the producer, the director, or…

Well, it depends. In the beginning, when I was working at Fox with Louis Silvers, we never saw the producer or director. We got the word from on high, and he would say so and so. If there was a difference of opinion we would sometimes talk to them on the phone, but it was not until I began work on LAURA that I actually came into contact with the producers or directors.

LAURA was your first big score.

Well, LAURA is the first one the public knew about. Before that I had done a lot of work, I was known in the profession. That’s how I had managed to wind up with LAURA, but LAURA was the first one I did that made a big smash and from then on I could call the shots.

How did you become involved with that film?

It’s a funny story. When I saw LAURA, the next day I had a conference with Otto Preminger and AI Newman. Preminger had tried to get the rights to use ‘Summertime’, but Ira Gershwin had refused to let him use it, so then he tried to get ‘Sophisticated Lady’ and that’s what he told me he was going to use. I told him it was wrong. Al Newman said: “You’ll never know what this guy will come up with, Otto, why don’t you give him a chance.” And one day I walked up with LAURA, and that was that.

After Fox, you went to MGM…

No, I freelanced. Even for a while I didn’t work at all. I spent several periods not working; because I was considered to be impossibly arrogant. It was only partially true.

Your music was too difficult, too sophisticated…

The violinists used to say they were afraid to put their fingers where it said. I was considered not only too far advanced as a musician, but also arrogant because I did not automatically agree with what directors said. I nevertheless made great friends among the producers, e.g. Richard Zanuck. After LAURA I could do no wrong and after FOREVER AMBER he was fascinated. AI Newman said to me Zanuck used to say: “What is that nut up to now?”

You also worked for Vincente Minnelli on THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL.

Yes and John Houseman. That was a marvellous experience. That tune, which is a famous tune, almost did not get in the film. Stephen Sondheim once told me it was the finest melody ever composed for a film. I came in and wrote it over a weekend, and I realized it was too complicated for me to show it on the piano to Minnelli and Houseman. So, Johnny Green, who was the head of the music department, allowed me to make a demonstration record with the orchestra. We did that and I went to John Houseman to play it. He was not in his office, so I went to Minnelli’s office where there was a phonograph and I played it. There were 2 other people in there and Minnelli and Houseman looked at one another and said: “What the hell is that!?!” When that happens you are in terrible trouble. What will the audience think? Fortunately these two other people, who both knew music, thought it was a beautiful piece and so I played it again and one more time and finally Houseman and Minnelli said: “That’s great!” Those two people were Adolph Green and Betty Comden and they are responsible for that piece still being in the picture.

You also scored several westerns. APACHE has a non-typical western score. What was it like, working with Robert Aldrich?

Bob Aldrich was very strange. He didn’t know what to make of that score and he wondered why there weren’t more melodies. “Look, you got this guy running around and shooting people in the throat with arrows, he burns down a fort and you want me to write melodies!” It was dumb, because there was a big melody in it played by a recorder.

WILL PENNY…

It’s one of my favourites, but it was also to some extent butchered by the ‘Great Mister Heston’. He put his nose in where it was not wanted and he ruined several scenes. There is one place where he is all tied up, lying in bed, trying to get out. The director, Tom Gries, (a marvellous man and one of my favourite directors) and the producer Walter Seltzer all agreed and the music department said, no music there, and I didn’t write any music, because silence would be better.

I went to see it later and I found out they had put music in it. They took it from other scenes and it sounds ridiculous. There were other things. ‘They were in trouble financially, because they were so far over budget. So Bill Stinson, the head of the music department and a wonderful music cutter (he had been my music cutter on CARRIE) asked me if I could write music we could use in several scenes. So I took a long scene at the end and I wrote the whole piece and I found out that if I took out a bar here and there, it would fit the cues in the other scenes too. So it was used in 2 or 3 different scenes and it was great fun to do that. It saved them a lot of money.

You also scored several cartoons, even Mr. Magoo cartoons.

I loved to do them. I did only one Mr. Magoo: SLOPPY JALOPY, but that’s one of my favourites and you can hardly hear a note of music in it. They didn’t tell me it was going to be nine tenths sound effects. The director, Pete Burness, told me the music had to be frantic, but there are rollercoasters and you don’t hear a damn note of music. In all I did 4 cartoons, including THE UNICORN IN THE GARDEN, MADELINE and GIDDYAP.

It’s rather strange, a ‘serious’ composer who writes music for cartoons. They were usually done by people like Carl Stalling or Scott Bradley.

I’m not serious! I’m kidding. Scott Bradley was a man of genius. He was the first guy of all of us whoever had a major article written about his work. It was written by an American-Swedish composer, Ingolf Dahl. Bradley was a wizard. He’s my favourite cartoon composer. He was a wonderful little mosey man, inventive, brilliant.

You are the President of the Society for the Preservation of Film Music. You are sitting on an enormous treasure, but very few CD’s are being released…

The reason is that we have no finances. We live from hand to mouth, because we live on the generosity of all of us. I give my time for nothing, so does everybody else. The same goes for Elmer Bernstein or Henry Mancini. This year we will honour Ennio Morricone.

For the first time you’ve chosen a European composer.

But we picked a wonderful one.

The Society has 600 members…

The thing is, we live off the proceeds of that one big banquet, and all of us work for nothing, we give our own equipment when it’s necessary and all kinds of people work for us for free. There is one generous fellow who wants to remain anonymous and every so often he gives us $10,000.

You are not supported financially by a grant from the American government?

Nobody supports anything. If people get wind of the fact that you are doing something worthwhile, you are in trouble. For instance, MGM, the studio about which all the horrible things they say about Hollywood are true, – they have a bureaucracy of such a nature that they would wear you out fighting the system.

But if you could release more CD’s, like the ‘Tribute to Jerry Goldsmith’ one, then…

It costs a lot of money to do that, even if we get cooperation, and we try to be as legitimate as possible.

Which of your own scores would you like to see released on compact disc?

THE REDEEMER and SEPARATE TABLES. In SEPARATE TABLES there is a scene I had to redo, because they couldn’t understand why I did it the way I did it. I saw it as the battle of the sexes.

You are also a teacher of film music at several universities.

I started teaching in 1952, but I have only been doing it regularly since 1956 at USC (University of Southern California). I’m still teaching now at UCLA (University of California – Los Angeles) and shortly at the UCC, Santa Barbara.

How do you teach film music composition and technique?

I teach two thirds the art of composing such as it is, because nobody teaches composing. I once talked to one of my former students who is now head of the music department at USC. I told him he should change the name of the course which is ‘Theory and Composition’ to ‘Theory and Computation’, because that is what they are actually teaching. Nobody teaches how to develop whereas I do. So they are learning composition from me and then I talk to them about how you make the film and play them my music and show them my sketches. I did a seminar recently about THE REDEEMER at the Museum of Modern Art and I brought not only the film, I brought my sketches. One scene was 20 minutes long and they looked at the music and I explained to them how I wrote it.

Miklos Rozsa did some seminars too…

He was actually the second. I started doing it first. When Mickey got busy he asked me to take over the program.

There is a famous anecdote about you and Hitchcock. When Hitchcock was making LIFEBOAT in 1944, the director felt that since the entire action of the film took place in a lifeboat, in the middle of the ocean, no music was necessary, where would the music come from? And you said, “Ask Mr. Hitchcock to explain where the cameras come from and I’ll tell him where the music comes from.”

I’ve sat in audiences where other people claimed. Roy Prendergast, one of the best- informed people, finally decided to find out who it was and found out that it was me. It’s a funny incident, but there’s the sheer arrogance. Another story: John Ford, an amazing tough guy, was once asked why he didn’t have more music in some pictures. He replied: “Listen, when I have a whole bunch of cowboys being chased by a whole bunch of Indians or vice versa, I don’t want the whole damn orchestra in there.” After all it’s ridiculous to say that. Music is a convention in film.

Have you written any concert works?

I’ve done some work for the Library of Congress. They gave me an award. Imagine an award by this prestigious organization which has given previous awards only to people like Bartok, Schoenberg, Shostakovich, and Stravinsky… I’ve written a book for them which was called ‘Wonderful Inventions’. But people keep asking me to write concert pieces from my film music, so I made a few and they played them.

Does a complete list of your film work exist?

No, I don’t have one; never wrote one, because I was always embarrassed. I never used to say anything about the Chaplin thing either, until I finally wrote and told the story at the instigation of Arthur Knight, the film critic. I’ve written several other articles since and some of them will be published by the Library of Congress in a memoir about George Gershwin. A lot of the scores I did originally were with Buttolph and Mockridge and we are not, always credited. For instance, I did about one third of THE BLUE BIRD. It’s an Al Newman score, but Al was busy working on 2 other pictures, so he gave me the themes and I wrote 3 or 4 reels and Buttolph wrote one reel, all based on Al’s material.

You’ve worked with Schoenberg…

I’ve actually written an article about that which was published in the Journal of the Schoenberg Institute. He was a wonderful, marvellous, very loving man. He was much more broadminded than most people thought he was. One time somebody was making disparaging remarks about Shostakovich and Schoenberg turned on him like a tiger and said: “Never speak like that about Shostakovich, he is a composer born.” He admired his music. Would you expect that? I would do lessons for him and I would sometimes show him the music I was doing and he was always very wonderful about it. And when I came to see him one day, he said: “What are you doing?” (Raksin imitates Schoenberg). I told him I had just been assigned to a picture about airplanes and he said: “You will not find an example in Schubert!” When we had finished the lesson and he was showing me out he said: “Like bees, only bigger”. He was charming. I used to play ping pong with him. He played pretty well and he played for blood. Much later I met him at a concert at UCLA and my wife and I were sitting next to him and he asked: “What are you doing?” I said: “Nothing that would justify the amount of time and work that you spent on me.” He looked at me as if I was a toad and he said: “LAURA! LAURA!” How the hell did he know LAURA, but he knew it and apparently he thought it was worth doing?

This week I’ve met 2 of the greatest film composers ever, Elmer Bernstein and you!

Elmer is one of my dearest friends. He is one of the most astonishing guys in the profession. For a while he got lost doing lousy pictures. Let me quote what Bernard Herrmann used to say: somebody once said to Benny: “Mr Herrmann, why do you do so many lousy pictures?” He turned and he said in that cranky voice of his: “Because if I didn’t do them, I would starve to death.”