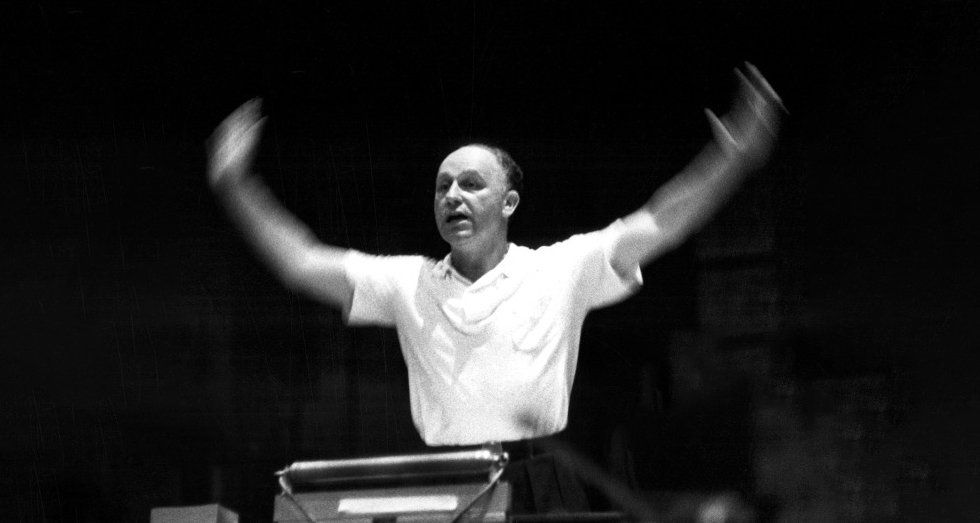

David Raksin

Source: Film Music Notes: September / October 1949

Publisher: New York: National Film Music Council

Copyright © 1949, by the National Film Music Council. All rights reserved.

David Raksin's is a complicated personality. It has more facets than even the circular point of view of a Picasso could concentrate into a single portrait. On the one hand Raksin is a wit, a wag, a wisecracker. He delights in puns, aphorisms, and anecdotes in which he himself is the central character. Humor gives way to indignation and sarcasm when he talks about critics who find fault with his music. For such detractors of his art, like the one who summed up the score for FOREVER AMBER with the adjective "loud," he invents verbal Schrechlichkeits of vivid and sometimes obscene imagery. Famous indeed are his lunch-table jeremiads, with which he invokes divine wrath upon evildoers in the film industry, in domestic politics, and in the councils of nations. At times he abandons himself to Hamlet's somber moods, or he will play, in his imagination, the role of a Manfred or a Job. Although he is suspected of enjoying these moods more than he ought, he is ever ready to be de-livered from them by a fine concert, a stimulating conversation or a compliment, preferably the last.

LAURA catapulted him to fame and fortune. For this highly sophisticated film melodrama dealing with the niceties of Park Avenue passions, Raksin invented the kind of tune that brings a blush to a maiden's cheek. It became a popular song by public demand. No sooner had Fox Studios released the picture than fan mail began pouring into the music department. What's that tune? Who wrote it? Enclosed please find twenty-five cents for a photograph of the composer. LAURA Clubs were being organized by college girls who sat through the picture three or four times in order to learn the melody and enjoy the guilty excitement of its luscious harmonies. This did not exclude appreciation on a somewhat higher plane: one of nearly 2000 fan letters came from a GI in France who was sure that he had heard the tune, perhaps in Beethoven? Made into a pop-song with lyrics by Johnny Mercer, LAURA sold over a half-million copies and more than a million records. It was on the Hit Parade for twelve weeks. And it was played by symphony orchestras, in luxurious arrangements such as the one recorded by Werner Janssen.

But LAURA, in spite of its earning power in royalties, was not an unmitigated blessing to its composer. Could its success be duplicated? Apparently not, at least so far, if one can judge by the comparative public apathy toward SLOWLY and FOREVER AMBER, the theme songs of subsequent pictures. At the same time Raksin cannot live LAURA down. "Can you write me another LAURA?" producers ask him when he presents himself as a candidate for a scoring job. It is some consolation that producers ask other composers the same question. Neither is it flattering for a composer to be referred to by columnists as a song-writer, especially when he has to his credit a number of orchestra and chamber-music scores and a large amount of music for films, radio and theatre. Raksin would have been glad enough to have been called a song-writer in the early days when he was making his way through the University of Pennsylvania playing saxophone and clarinet in dance bands and radio orchestras, or when he was working in New York as a member of the arrangers' staff at Harms, Inc. But after coming to Hollywood in 1935 to work on Chaplin's MODERN TIMES, his ambitions have been too serious and his achievements too noteworthy to be summed up by the term "song writing."

Among his colleagues, Raksin's extraordinary talent is ungrudgingly conceded. Ideas come abundantly although he subjects them to rigorous revision and polishing. During the working stages of a score, he courts the criticism of his friends and colleagues, and he follows it as often as not. He is prodigal of energy and pains no matter how unimportant a job may seem. The merest four-bar "bridge" for a radio drama is composed as thoughtfully as the main title for an epic. This is an economy of abundance, but hardly practical for composers less gifted and less conscientious than himself. What Raksin needs most at the moment, however, is a picture that will fully exercise his powers. FOREVER AMBER fell short of this requirement, for no music could have lifted this film out of the pit prepared for it by censorship, a mediocre script, and an undistinguished portrayal of the central characters. FORCE OF EVIL, though an excellent picture was not very successful; and the music, which was probably the best that Raksin has yet written, went unnoticed. Film criticism has not yet reached the point where it can discern the merits of a score in the context of a poor picture, although it frequently does this much for photography and acting and scenic designing. And music criticism has not yet reached the point where it is willing to give as much attention to a good film score as it gives to a mediocre symphony. But in this respect Raksin is no worse off than many of his colleagues.

On the whole, Raksin's music is as rich, luxurious and opulent as a tropical plant. Although it is consistently melodious, it tends somewhat to be over-written, laden with harmonic and contrapuntal complexity, and exotically orchestrated. Once, when he was studying with Arnold Schoenberg, he brought the master a few pages of a work-in-progress for examination and criticism. Schoenberg read it carefully, cocked his head to one side and said with disarming sweetness, "Don't you think this is just a little bit complicated?"

Whatever the complications were that Schoenberg was chiding him for, Raksin was doubtless too inexperienced a composer to recognize or correct them at the time. But he took the lesson to heart, finding as most composers do, that simplicity and directness are virtues very hard to come by. But every successive score of Raksin's marks a gain in this direction. Not that there is anything in them approaching austerity, anything to suggest that he might be contemplating a main title in two-part canon at the major seventh. For he deplores the pinched emotions being purveyed in the concert hall today by believers in "the cult of the inexpressive." He himself is a romanticist, in respect to both the emotional content of music and the techniques of composing it. This should not be construed as either a virtue or a vice, only as an inevitable manifestation of his personality. Still it must be acknowledged that one area of expressiveness is so far closed to him, the area of serenity, calm, repose. One is sometimes distressed by the constant movement of harmony and counterpoint, the entrances and exits of instruments, the crowding of musical events into a brief time-span. The still, small voice of contemplation is all too seldom heard. It seems hardly accidental that Raksin's current chore is the music for a Fox film called WHIRLPOOL.