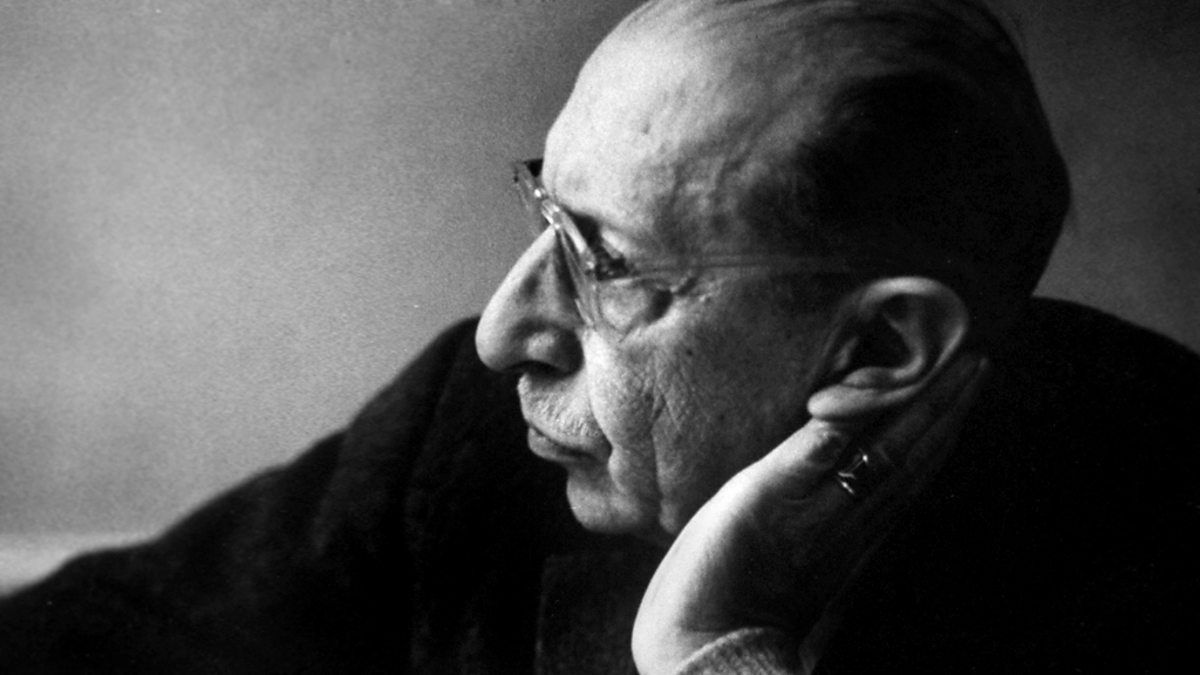

Igor Stravinsky on Film Music

Source: The Musical Digest, Vol. 28, No. 1 (September 1946), pp.

4, 5, 35, 36

Igor Stravinsky on Film Music as Told to Ingolf Dahl

What is the function of music in moving pictures? What, you ask, are the particular problems involved in music for the screen? I can answer both questions briefly. And I must answer them bluntly. There are no musical problems in the film. And there is only one real function of film music – namely, to feed the composer! In all frankness I find it impossible to talk to film people about music because we have no common meeting ground; their primitive and childish concept of music is not my concept. They have the mistaken notion that music, in "helping" and "explaining" the cinematic shadow-play, could be regarded under artistic considerations. It cannot be.

Do not misunderstand me. I realize that music is an indispensable adjunct to the sound film. It has got to bridge holes; it has got to fill the emptiness of the screen and supply the loudspeakers with more or less pleasant sounds. The film could not get along without it, just as I myself could not get along without having the empty spaces of my living-room walls covered with wall paper. But you would not ask me, would you, to regard my wall paper as I would regard painting, or apply aesthetic standards to it?

Misconceptions arise at the very outset of such a discussion when it is asserted that music will help the drama by underlining and describing the characters and the action. Well, that is precisely the same fallacy which has so disastrously affected the true opera through the "Musikdrama." Music explains nothing; music underlines nothing. When it attempts to explain, to narrate, or to underline something, the effect is both embarrassing and harmful.

What, for example, is "sad" music? There is no sad music, there are only conventions to which part of the western world has unthinkingly become accustomed through repeated associations. These conventions tell us that Allegro stands for rushing action, Adagio for tragedy, suspension harmonies for sentimental feeling, etc. I do not like to base premises on wrong deductions, and these conventions are far removed from the essential core of music.

And – to ask a question myself – why take film music seriously? The film people admit themselves that at its most satisfactory it should not be heard as such. Here I agree. I believe that it should not hinder or hurt the action and that it should fill its wallpaper function by having the same relationship to the drama that restaurant music has to the conversation at the individual restaurant table. Or that somebody's piano playing in my living-room has to the book I am reading.

The orchestral sounds in films, then, would be like a perfume which is indefinable there. But let it be clearly understood that such perfume "explains" nothing; and, moreover, I can not accept it as music. Mozart once said: "Music is there to delight us, that is its calling." In other words, music is too high an art to be a servant to other arts; it is too high to be absorbed only by the subconscious mind of the spectator, if it still wants to be considered as music.

Furthermore, the fact that some good composers have composed for the screen does not alter these basic considerations. Decent composers will offer the films decent pages of background score; they will supply more "listenable" sounds than other composers; but even they are subject to the basic rules of the film which, of course, are primarily commercial. The film makers know that they need music, but they prefer music which is not very new. When, for commercial reasons, they employ a composer of repute they want him to write this kind of "not very new" music – which, of course, results in nothing but musical disaster.

I have been asked whether my own music, written for the ballet and the stage, would not be comparable in its dramatic connotation to music in the films. It cannot be compared at all. The days of Petrouchka are long past, and whatever few elements of realistic description can be found in its pages fail to be representative of my thinking now. My music expresses nothing of realistic character, and neither does the dance. The ballet consists of movements which have their own aesthetic and logic, and if one of those movements should happen to be a visualization of the words "I Love You," then this reference to the external world would play the same role in the dance (and in my music) that a guitar in a Picasso still-life would play: something of the world is caught as pretext or clothing for the inherent abstraction. Dancers have nothing to narrate and neither has my music. Even in older ballets like Giselle, descriptiveness has been removed – by virtue of its naiveté, its unpretentious traditionalism and its simplicity – to a level of objectivity and pure art-play.

My music for the stage, then, never tries to "explain" the action, but rather it lives side by side with the visual movement, happily married to it, as one individual to another. In Scènes de Ballet the dramatic action was given by an evolution of plastic problems, and both dance and music had to be constructed on the architectural feeling for contrast and similarity.

The danger in the visualization of music on the screen – and a very real danger it is – is that the film has always tried to "describe" the music. That is absurd. When Balanchine did a choreography to my Danses Concertantes (originally written as a piece of concert music) he approached the problem architecturally and not descriptively. And his success was extraordinary for one great reason: he went to the roots of the musical form, of the jeu musical, and recreated it in forms of movements. Only if the films should ever adopt an attitude of this kind is it possible that a satisfying and interesting art form would result.

The dramatic impact of my Histoire du Soldat has been cited by various critics. There, too, the result was achieved, not by trying to write music which, in the background, tried to explain the dramatic action, or to carry the action forward descriptively, the procedure followed in the cinema. Rather was it the simultaneity of stage, narration, and music which was the object, resulting in the dramatic power of the whole. Put music and drama together as individual entities, put them together and let them alone, without compelling one to try to "explain" and to react to the other. To borrow a term from chemistry: my ideal is the chemical reaction, where a new entity, a third body, results from uniting two different but equally important elements, music and drama; it is not the chemical mixture where, as in the films, to the preordained whole just the ingredient of music is added, resulting in nothing either new or creative. The entire working methods of dramatic film exemplify this.

All these reflections are not to be taken as a point-blank refusal on my part ever to work for the film. I do not work for money, but I need it, as everybody does. Chesterton tells about Charles Dickens' visit to America. The people who had invited him to lecture here were astonished, it seems, about his interest in fees and contracts. "Money is not a shocking thing to an artist," Dickens insisted. Likewise there will be nothing shocking to me in offering my professional capacities to a film studio for remuneration.

If I am asked whether the dissemination of good concert music in the cinema will help to create a more understanding mass audience, I can only answer that here again we must beware of dangerous misconceptions. My first premise is that good music must be heard by and for itself, and not with the crutch of any visual medium. If you start to explain the "meaning" of music you are on the wrong path. Such absurd "meanings" will invariably be established by the image, if only through automatic association. That is an extreme disservice to music. Listeners will never be able to hear music by and for itself, but only for what it represents under the given circumstances and given instructions. Music can be useful, I repeat, only when it is taken for itself. It has to play its own role if it is to be understood at all. And for music to be useful to the individual we must above all teach the self-sufficiency of music, and you will agree that the cinema is a poor place for that! Even under the best conditions it is impossible for the human brain to follow the ear and the eye at the same time.

And even listening is itself not enough, granted that it be understood in its best sense; the training of the ear. To listen only is too passive and it creates a taste and judgment which are too general, too indiscriminate. Only in limited degree can music be helped through increased listening; much more important is the making of music. The playing of an instrument, actual production of some kind or another, will make music accessible and helpful to the individual, not the passive consumption in the darkness of a neighborhood theatre.

And it is the individual that matters, never the mass. The "mass," in relationship to art, is a quantitative term which has never once entered into my

considerations. When Disney used Sacre du Printemps for Fantasia he told me: "Think of the number of people who will thus be able to hear your music!" Well, the number of people who will consume music is doubtless of interest to somebody like [impresario] Mr. [Sol] Hurok, but it is of no interest to me. The broad mass adds nothing to the art, it cannot raise the level, and the artist who aims consciously at "mass-appeal" can do so only by lowering his own level. The soul of each individual who listens to my music is important to me, and not the mass feeling of a group. Music cannot be helped through an increase in quantity of listeners, be this increase effected by the films or any other medium, but only through an increase in the quality of listening, the quality of the individual soul.

In my autobiography I described the dangers of mechanical music distribution; and I still believe, as I then did, that "for the majority of listeners there is every reason to fear that, far from developing a love and understanding of music, the modern methods of dissemination will . . . produce indifference, inability to understand, to appreciate, or to undergo any worthy reaction. In addition, there is the musical deception arising from the substitution for the actual playing of a reproduction, whether on record or film or by wireless transmission. It is the same difference as that between the synthetic and the authentic. The danger lies in the fact that there is always a far greater consumption of the synthetic which, it must always be remembered, is far from being identical with its model. The continuous habit of listening to changed and sometimes distorted timbres dulls and degrades the ear, so that it gradually loses all capacity for enjoying natural musical sounds."

In summary, then, my ideas on music and the moving pictures are brief and definite:

The current cinematic concept of music is foreign to me; I express myself in a different way. What common language can one have with the films? They have recourse to music for reasons of sentiment. They use it like remembrances, like odors, like perfumes which evoke remembrances. As for myself, I need music for hygienic purposes, for the health of my soul. Without music in its best sense there is chaos. For my part, music is a force which gives reason to things, a force which creates organization, which attunes things. Music probably attended the creation of the universe.