Life with Charlie

Source: The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Summer 1983), pp. 234-253

Publisher: Library of Congress

Copyright © The Raksin Estate. Reprinted by permission.

The new adventure began on August 8, 1935, four days after my twenty-third birthday, with a telegram from Eddie Powell, addressed to me “care Harms Inc.” in New York City. Since I was in Boston, arranging and orchestrating music for AT HOME ABROAD, a show that was in its pre-Broadway tryout, the people at Harms forwarded the wire to me. It said:

HAVE WONDERFUL OPPORTUNITY FOR YOU IF INTERESTED IN HAVING SHOT AT HOLLYWOOD STOP CHAPLIN COMPOSES ALMOST ALL HIS OWN SCORE BUT CANT WRITE DOWN A NOTE YOUR JOB TO WORK WITH HIM TAKE DOWN MUSIC STRAIGHTEN IT OUT HARMONICALLY DEVELOP HERE AND THERE IN CHARACTER OF HIS THEME PLAY IT OVER WITH PICTURE FOR CUES WE WILL ORCHESTRATE TOGETHER NEWMAN CONDUCT STOP BEST CHANCE YOU COULD EVER HAVE TO BREAK IN HERE CHAPLIN FASCINATING PERSON ALTHOUGH MUSIC VERY SIMPLE AM SURE NEWMAN WILL LIKE YOU AND KEEP YOU HERE YOU SPENCER AND I CAN HAVE GRAND TIME WORKING TOGETHER STOP THIS OFFER TWO HUNDRED PER WEEK MINIMUM OF SIX TRANSPORTATION BOTH WAYS STOP YOU CAN STUDY WITH SCHOENBERG WHILE HERE I HAVE SOLD YOU TO NEWMAN BECAUSE FEEL HOLLYWOOD PROVIDES BEST OPPORTUNITY FOR YOUR DEVELOPMENT AS COMPOSER AND ORCHESTRATOR CAN ALSO GET YOU IN WITH MAX STEINER AT END OF THIS JOB IF YOU WISH ANSWER IMMEDIATELY BY WESTERN UNION REGARDS.

That yellow page, with its strips of uppercase letters pasted on, has reposed in my abandoned scrapbook for quite a while, and I will bet this is the first time I have looked at it - really looked - since I put it there so long ago. It is not likely that I shall ever get to ride one of those magnificent rockets to the moon; but I doubt that the moment that followed “We have ignition… we have lift-off!” could have been more thrilling to the fellows in the Columbia than the one after “ANSWER IMMEDIATELY” was to me.

There I was, fresh from the University of Pennsylvania, survivor of a harrowing year in New York City that included plenty of supper-less evenings - to remind me that not every young composer has it as easy as Felix Mendelssohn did. When the society dance band with which I had come to New York from my home in Philadelphia developed a case of chronic underemployment, the leader elected to withdraw to safer ground on the Main Line, and the band followed.

I was the only one who stayed in the big town, and I only managed that because our first saxophone player gave me what was left of a due bill as a farewell gift. This was a modest document which promised lodging and services in an equally modest Manhattan hotel in return for space in some trade magazine or journal. Hotels would tender these in lieu of cash payment for advertising. How my friend Milton Schatz, mellow-toned leader of the section in which I played tenor saxophone, came by this due bill I am not likely to discover at this late date; but it saved me. Although things got so bad for this one-more-unknown-too-many in a town already overloaded with them that I often went hungry, at least I had a place to sleep.

It was out of the question to seek help from home. My father was then struggling to recover from an illness that would eventually prove fatal. And I was too proud to appeal to anyone else for help. If I had also been homeless - on the street - I do not know whether my resolve would have held. But, secure in my spartan little room on Forty-eighth Street just east of Broadway, I dreamed my dreams and woke up happy and refreshed. After a while there were a few playing jobs with various pickup bands, and the word was passed around that there was a new "tenor man" available who could handle anything from the society repertoire to improvisation and was also a talented arranger. And thus began the series of breaks that eventually landed me on a network radio program, as arranger for the Fred Allen Show.

In those days radio was the top-dollar work for musicians, and the best programs hired the cream of the crop for their orchestras. The pianist of this one was the redoubtable Oscar Levant, with whom I soon struck up a friendship, probably based upon mutual curiosity and, on my part, an unsuspected ability to endure uncertainty; for friendship with Oscar was what platonic love with a minefield must be like. One evening the radio program was to feature my arrangement of Gershwin's “I Got Rhythm,” an ingenious concoction in which I had counterpointed several themes from that composer's An American in Paris to the melody of the song. Levant alerted Gershwin to listen, and when the program was over I had made a new friend (whom, however, I would not meet until several years later in Hollywood). George liked the arrangement enough to recommend me to his publishers, Harms, Incorporated, whose catalogs included nearly every important musical of that day. Among their clients were Jerome Kern, Vincent Youmans, Cole Porter, Arthur Schwartz, Harold Arlen, Vernon Duke, and Richard Rodgers - just about all of the leading lights of the American musical theater. They also maintained a distinguished staff of arrangers, including Robert Russell Bennett, Hans Spialek, Don Walker, and Conrad Salinger. Before he left for Hollywood, Eddie Powell had also been a member of this elite group, which I now joined; and it was in that capacity that I was in Boston, working on At Home Abroad, when Eddie's telegram arrived.

There are some excitements that transcend the professional's creed of playing it cool - appearing unruffled, or simulating imperviousness when circumstances are either too good or too bad to bear. And this qualified as one of those, which meant that I was allowed some leeway in demeanor, some youthful elation as the telegrams and telephone calls flew thick and fast. Hans Spialek came up to Boston to take over for me, which was a bit like having Babe Ruth batting for some promising rookie. In a few days I was aboard the Twentieth Century Limited, bound for glory and making the most of my new status as a member of the expense account aristocracy.

City skyline

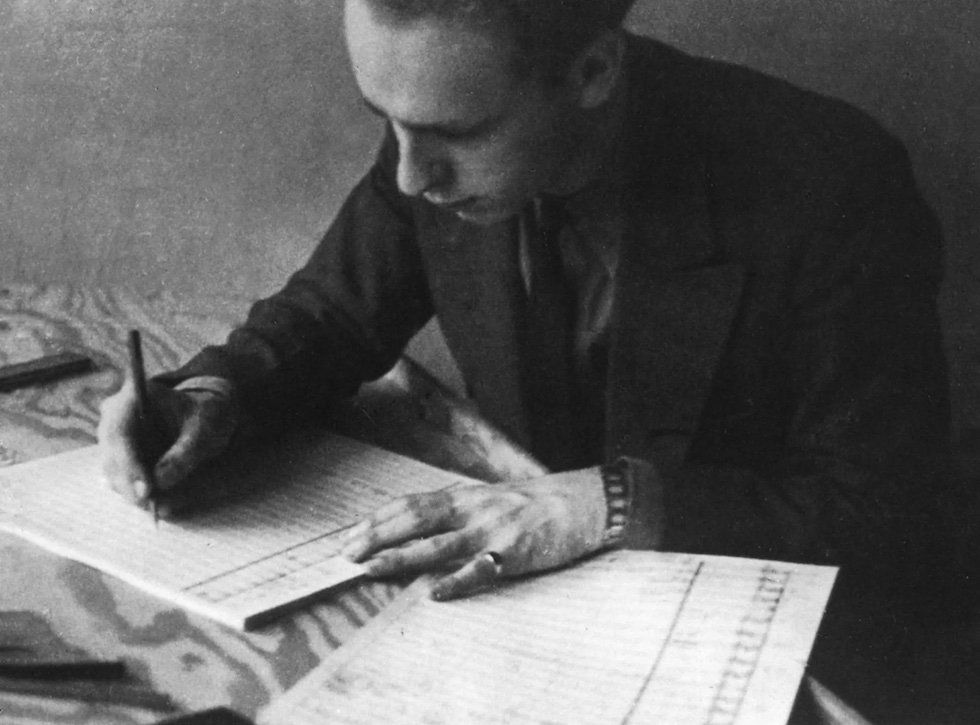

David Raksin, orchestrating a sequence for the MODERN TIMES score at the United Artists studio in 1935.

Photo by Carter de Haven, Jr.

Four lovely, sybaritic days later I arrived at the Pasadena station, to be met by two of the great masters of the orchestra whom our country has produced. Herb Spencer (who is mentioned in the telegram) is a brilliant musician who came to the United States from his native Chile to study and remained to make a great name for himself in our profession. Today he is the admired orchestrator of John Williams's scores for such films as STAR WARS and CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND. Eddie Powell is renowned for his elegant and fastidious work as orchestrator of Alfred Newman's film scores. What was, however, more important in August of 1935 was that he and Herb turned up to meet me in Eddie's new LaSalle convertible - which is an ideal way of impressing upon a traveler that he has made it to Hollywood. And indeed, when we glided down Sunset Boulevard into what seemed a veritable parade of convertibles filled with beautiful girls, I knew that I had come to the right place.

Paradise found, some might say - but not quite yet. I am not sure whether what happened next would have surprised the inhabitants of sixth-century Sybaris; but it came as a rude awakening when at dinner Powell and Spencer informed me that our next stop would be the United Artists Studio, where I would be pressed into service to help them make up the time they had expended on the welcoming festivities. It seemed that a recording had been scheduled for the next morning; Alfred Newman would be conducting the score of a new Goldwyn picture, BARBARY COAST, and Eddie and Herb still had a mountain of sketches to orchestrate before the copyists came in at 3:00 A.M. To be called upon so soon to lend one's talent in an enterprise for which one has no experience is quite a compliment. It is also unnerving.

Since Powell and Spencer were using the only two music studios on the United Artists lot, they took me over to a sound stage where there was a piano. Eddie gave me a list of the instruments that would be available at the recording and several very sparse sketches of film sequences written in a hand with which I was to become extremely familiar in time, the musical script of Al Newman. I had met him earlier that day - a small, intense, and dapper man who exuded power and strong cologne. He had asked a question, seemingly innocuous, about the way in which I viewed the assignment, the challenge of the project itself, and the prospect of working with one of the great film artists, Chaplin. It was soon obvious that my reply had left him wondering what his two associates could have been thinking when they recommended me; he appeared to be put off by my enthusiasm. This was not my first experience with the chill of disapproval but, had I been in his place, I would have judged any young man not inspired to rhapsodies by such good fortune to be temperamentally unfit for the job. Still, the encounter left me wondering what kind of man could have considered my response some kind of social gaffe.

And that disconcerting thought kept me company as I worked alone in the vast emptiness built to accommodate film scenery and production equipment. Eddie and Herb had generously started me out with the relatively easy task of making several string arrangements of a Stephen Foster melody that Newman was interpolating in the score of Barbary Coast. The sequences had already been timed to synchronize with the film footage, and my job was to make elaborate settings of the tune for a large group of strings. I was well prepared for that; but when from time to time the memory of Newman's raised eyebrow materialized I knew for sure that if my work turned out to be in any way below the standard which he set I would be on the train back to New York the next afternoon.

Fortunately, in such cases the work itself becomes the indicated therapy. I got lost in the intricacies of the task at hand, and when my two friends showed up near midnight, ostensibly to bring me coffee but actually to see how I was doing, it was evident from their expressions of approval that I had not disappointed them. Newman's chief copyist, Fred Combattente, arrived as I was finishing the last of the sequences and seemed relieved to find my manuscript legible.

After a few hours of sleep, Eddie, Herb, and I went together to the recording session on stage 7, where I witnessed for the first time Al Newman's virtuosity with an orchestra. The sound he got from his hand-picked ensemble was nothing less than gorgeous, and his ability to elicit beautiful and impeccable playing at extremely slow tempi was a revelation to me. For some reason, I failed to anticipate what this style of conducting would do for the notes I had set down during the long night, so that when he turned his attention to one of those sequences I did not immediately connect the glowing sounds that emerged from the orchestra with the monochromatic symbols I had written on the score pages. When he had read through the first of my arrangements, Newman put down his baton and summoned me to the podium, where he introduced me to his musicians in a manner that left me blushing.

Newman and I were to go through a relationship during the years when we worked together that was almost familial in its intensity; but at that moment a bond was established that survived serious differences of purpose between us. Many years later, after Al died, his son Tommy entered my class in composition at the University of Southern California. And one day, trying to explain to him why it meant so much to me to find the son of my old mentor in my class, I told him that I had at one time been another son of his father’s.

I think it was on the day after the BARBARY COAST recording that I went to Chaplin's headquarters, near the corner of Sunset Boulevard and La Brea, to meet the great man. The studio had a facade of one-story brick buildings with Tudor-style timbers inset (1); behind these were several moderate-sized film stages. In his projection room, a small theater, Chaplin awaited me. For some reason, it often seems to surprise me to find that great artists are really people. I have met perhaps more than my share of them, because so many have spent time in Hollywood, and I am always amazed that they somehow lack the wings, or the X-ray vision, or the noble proportions to which (some misconceived synapse keeps telling me) their genius entitles them. The man who stood before me was certainly exotic enough—from his abundant white hair to his anachronistic shoes with their high suede tops and mother-of-pearl buttons—and urbane to match. But he was neither twelve feet tall nor two-dimensional; yet, so charming and gracious that I was immediately captivated.

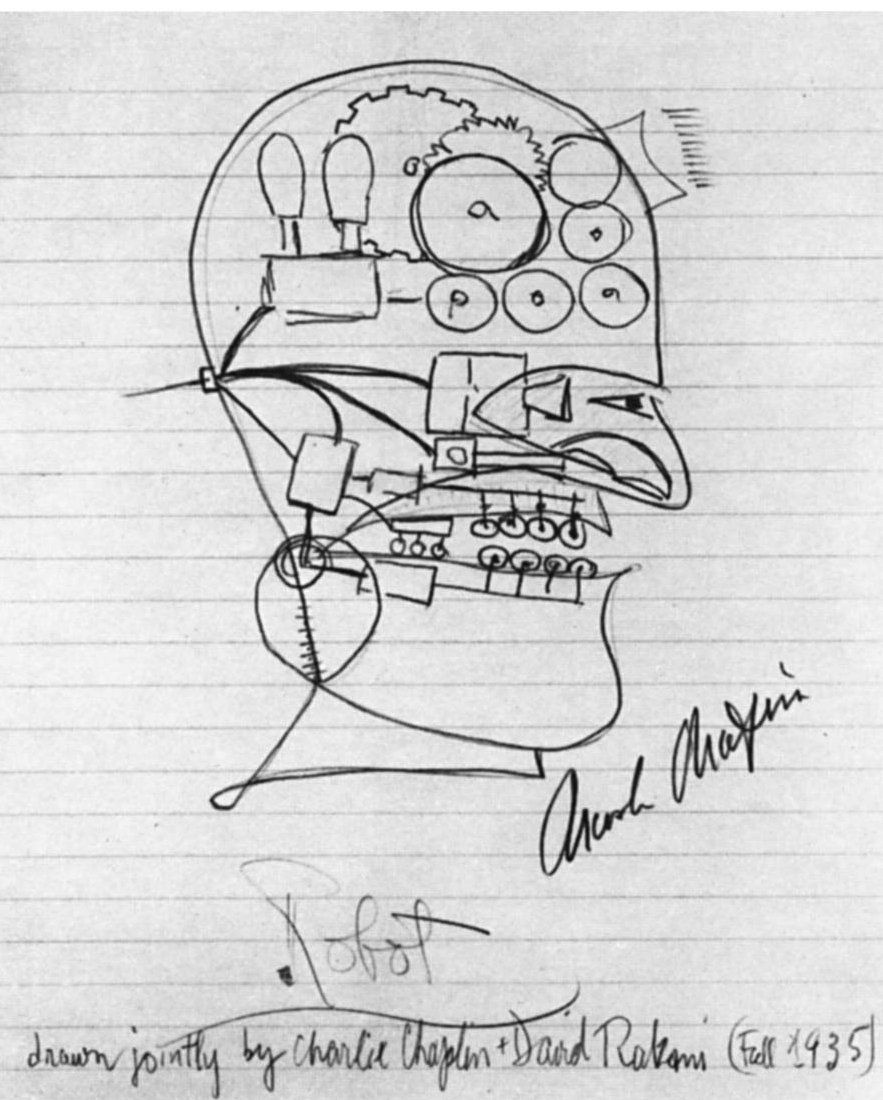

In the years since that meeting, it has never occurred to me to wonder how I appeared to Chaplin. But this article has sent me searching through my souvenirs for photographs and other memorabilia; and among the curiosities that surfaced was a page of yellow foolscap on which I copied down his very words, as related to me by the playwright, Bayard Veiller (2), to whom Chaplin introduced me one day at the Beverly Hills Brown Derby. According to Veiller, Charlie said, “They tell you, ‘I’ve got just the man for you - brilliant, experienced, a composer, orchestrator, and arranger with several big shows in his arranging cap’ - and this infant turns up!

”Since this happened before the decades during which it was revealed that talent is the exclusive province of the young, Charlie may indeed have had misgivings. If so, he overcame them sufficiently to show me the new film. MODERN TIMES was then in a first-final edit, meaning that substantial changes were now unlikely, although fine tuning could, and would, continue beyond production deadlines and right down to the wire; a measure of Chaplin's hard-won independence from the stranglehold of studio policy.

City skyline

David Raksin with Charlie Chaplin in the projection room of the Chaplin studio on LaBrea in 1952. Chaplin spent part of his last day in Hollywood reminiscing with Raksin. Courtesy of Francis O'Neill.

I loved the picture at once, and I laughed so hard at some of the scenes (particularly the feeding machine sequence) that some time later Charlie told me he had wondered whether I was exaggerating for his benefit. By the time that came up, however, he knew better; for after about a week and a half of working together a serious difference of opinion as to the precise nature of my job arose between us, and I was summarily fired.

Like many self-made autocrats, Chaplin demanded unquestioning obedience from his associates; years of instant deference to his point of view had persuaded him that it was the only one that mattered. And he seemed unable, or unwilling, to understand the paradox that this imposition of will over his studio had been achieved in a manner akin to that which he professed to deplore in MODERN TIMES. I, on the other hand, have never accepted the notion that it is my job merely to echo the ideas of those who employ me; and I had no fear of opposing him when necessary, because I believed he would recognize the value of an independent mind close at hand.

When I think of it now, it strikes me as appallingly arrogant to have argued with a man like Chaplin about the appropriateness of the thematic material he proposed to use in his own picture. But the problem was real. There is a specific kind of genius that traces its ancestry back to the magpie family, and Charlie was one of those. He had accumulated a veritable attic full of memories and scraps of ideas, which he converted to his own purposes with great style and individuality. This can be perceived in the subject matter, as well as the execution, of his story lines and sequences. In the area of music, the influence of the English music hall was very strong, and since I felt that nothing but the best would do for this remarkable film, when I thought his approach was a bit vulgar I would say, “I think we can do better than that.” To Charlie this was insubordination pure and simple—and the culprit had to go.

The task of informing me was given to Eddie Powell, in whose studio I was living at the time; and although he relayed the unhappy news as gently as possible it just about broke my heart. The next evening, Eddie and his wife, Kay, and Herb Spencer took me to a favorite Hollywood hangout, Don the Beachcomber's, for dinner. At one point I was so overcome with unhappiness that I walked to the doorway quickly and stood there struggling for control. Just then, someone tapped me on the shoulder, and when I turned around I saw it was Al Newman. “I've been looking at your sketches,” he said, “and they're marvelous - what you're doing with Charlie's little tunes. He'd be crazy to fire you.

”I was packing the next day when there was a phone call from Alf Reeves, an endearing old gentleman who had worked with Chaplin years before in the Fred Karno troupe and was now general manager of the studio. I went to see him, and he said that they wanted to hire me again. I replied that I would like nothing more, but that before I could give him an answer I wanted to talk to Charlie - alone - otherwise the same thing would happen again. So Charlie and I met in his projection room and had it out.

I explained that if it was a musical secretary he wanted he could hire one for peanuts; if he wanted more "yes" men, well, he was already up to his ears in them. But if he needed someone who loved his picture and was prepared to risk getting fired every day to make sure that the music was as good as it could possibly be, then I would love to work with him again. We shook hands, and he gave me a sharp tap on the shoulder - and that was it, the beginning of four and a half months of work and some of the happiest days of my life.

Charlie would usually arrive at the studio in midmorning, at which point the staff, which had been notified that he was en route, would spring into activity; Carter de Haven, Jr., the son of one of Chaplin's cronies (and now a film producer), would alert me. I would put aside the sketches of the previous day or so, on which I was working, and join Charlie in the projection room. Our equipment included a small grand piano, a phonograph, a portable tape recorder, a large screen for the 35 mm projectors, and a smaller one for the “Goldberg,” a projection movieola that could also back up in sync.

When he appeared, Charlie was generally armed with a couple of musical phrases; in the beginning, apparently because he thought of me as an innocent, he seemed to enjoy telling me that he got some of his best ideas “while meditating [raising of eyebrow] - on the throne, you know.” Innocent or not, few composers can afford to be squeamish about the loci of the muse, so unless one of us had some other idea that could not wait we would first review the music leading to the sequence at hand and then go on to the new ideas. First, I would write them down; then we would run the footage over and over, discussing the scenes and the music. Sometimes we would use his tune, or we would alter it, or one of us might invent another melody. I should say that I always began by wanting to defer to him; not only was it his picture, but I was working from the common attitude that since I was ostensibly the arranger the musical ideas were his prerogative.

Here it may be valuable to discuss the nature of the collaboration which Chaplin found necessary, and which has invariably been misinterpreted. For example, in an article by one of Chaplin's biographers, Theodore Huff (3), in the very first paragraph we read, “When CITY LIGHTS first appeared with the credit title ‘Music composed by Charles Chaplin’… [people] assumed that Chaplin was stretching it a bit in order that the public be certain that from him came everything in the film.” The fact is that in CITY LIGHTS, as in all of his films, Chaplin was assisted by another composer; in that instance it was Arthur Johnston (“Cocktails for Two,” “Pennies from Heaven”). I do not know how large a part Johnston played in that score, but I did discuss the music for The Great Dictator with the man who assisted Chaplain on that film.

The Great Dictator was Charlie's first real talkie; although he had used a sound track in CITY LIGHTS and MODERN TIMES, he had only been heard in the “Titina” sequence of the latter film. The composer who worked with Chaplin on THE GREAT DICTATOR was Meredith Willson (THE MUSIC MAN), an old friend who authorized me to quote him: “I know you will want to make it clear that Charlie was a very brilliant man, a very creative man. He would come into the studio they had given me to work in, and he would have ideas to suggest - melodies. After that, he would leave me alone. When he came in to see me again I would show him what I was doing, and often he would have very good suggestions to make. He liked to act as though he knew more music than he actually did, but his ideas were very good.” (It is interesting to note that in James Limbacher's book Film Music, p. 333, Chaplin and Willson are listed as co-composers of the score for THE GREAT DICTATOR.)

From Meredith's account of his experience, it seems clear that he had more to do with the score for THE GREAT DICTATOR than I had with MODERN TIMES. Charlie and I worked hand in hand. Sometimes the initial phrases were several phrases long, and sometimes they consisted of only a few notes, which Charlie would whistle, or hum, or pick out on the piano. Thus far, it does not seem too different from what Willson has recounted. But here the differences begin. Where Meredith retreated to his studio to write, I remained in the projection room, where Charlie and I worked together to extend and develop the musical ideas to fit what was on the screen. When you have only a few notes or a short phrase with which to cover a scene of some length, there must ensue considerable development and variation - what is called for is the application of the techniques of composition to shape and extend the themes to the desired proportions. (That so few people understand this, even those who may otherwise be well informed, makes possible the common delusion that composing consists of getting some kind of micro-flash of an idea, and that the rest of it is mere artisanry; it is this misconception that has enabled a whole generation of hummers and strummers to masquerade as composers.)

Theodore Huff and others to the contrary, no informed person has claimed that Charlie had any of the essential techniques. But neither did he feed me a little tune and say, “You take it from there.” On the contrary; we spent hours, days, months in that projection room, running scenes and bits of action over and over, and we had a marvelous time shaping the music until it was exactly the way we wanted it. By the time we were through with a sequence we had run it so often that we were certain the music was in perfect sync. Very few film composers work this way (Erich Korngold did work in a projection room, and a few others - Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and Jerry Goldsmith come to mind - used movieolas); the usual procedure is to work from timing sheets, with a stop clock, to coordinate image and music. But MODERN TIMES was my first job in Hollywood, and I did not learn the sophisticated system of visual cueing until I took my sketches to Al Newman's assistant, Charles Dunworth, who devised the “Newman” system. Dunworth took my timing and sync marks and transferred them to the film, so that during the recording sessions they would appear on the screen as streamers (white lines moving across the screen to indicate sync points) and punches (mathematically calculated holes punched in specific film frames.

Chaplin had picked up an assortment of tricks of our trade and some of the jargon and took pleasure in telling me that some phrase should be played “vrubato,” which I embraced as a real improvement upon the intended Italian word, which was much the poorer for having been deprived of the v. Yet, very little escaped his eye or ear, and he had suggestions not only about themes and their appropriateness but also about the way in which the music should develop, whether the melodies should move “up” or “down,” whether the accompaniment should be tranquil or “busy.” I recall an earnest discussion about a certain melody (or counter melody). I had suggested that we had already used the tune in the middle and upper registers and that it was time we played it in the lower register; by the time Charlie and I had explored the possibilities, we had eliminated the French horn as having too soft an edge, the trombone as being too declamatory, the bassoon as a bit too mild, and I think we wound up using a tenor saxophone there.

The result of this process was a series of sketches, quite specific as to principal musical lines and cueing to the action on the screen, but far from complete as to harmonies, subsidiary lines and voice leading, and instrumentation. While we were working at full momentum, it would have been foolish for me to keep Charlie standing there while I meticulously filled in all of the parts. So this first set of sketches was rather sparse, except that when an idea was clearly revealed I felt it worthwhile to speed write the whole thing immediately. Sometimes Charlie would attend to other matters while this was going on, or do his improvisations; more often than not he just stood around and kibitzed while I scribbled away. But most of the time I would settle for the shorthand sketch, and would either clean it up or rewrite it legibly in the mornings before he arrived at the studio or, if we had not worked after dinner, I would clear up my sketches at home; I often worked on weekends. (I still have a set of the rather primitive first sketches; but what has become of the more complete set from which Eddie Powell and I would later orchestrate the score for recording I do not know. I am afraid they may have been lost in the fire that destroyed the Powells' house in Beverly Hills.)

Sometimes in the course of our work, when the need for a new piece of thematic material arose, Charlie might say, “A bit of ‘Gershwin’ might be nice there.” He meant that the Gershwin style would be appropriate for that scene. And indeed there is one phrase that makes a very clear genuflection toward one of the themes in Rhapsody in Blue. Another instance would be the tune that later became a pop song called “Smile.” Here, Charlie said something like, “What we need here is one of those ‘Puccini’ melodies.” Listen to the result, and you will hear that, although the notes are not Puccini's, the style and feeling are.

When, in 1978, Prof. Charles Berg, of the University of Kansas at Lawrence, asked me if I would answer some questions about the music for MODERN TIMES, I thought at first to decline. Over the years I had tried to be exceptionally discreet on that subject (4). During the time when I worked with Chaplin, and for quite a while before and after, he was persona non grata with many people out here, partly as a result of his extreme independence and partly because of his politics, which were consistently (even deliberately) misinterpreted as radical. Much of the animosity toward him reflected the all too common wish to bring down an envied figure; the rest can be understood as the product of the Great Hollywood Lunatic Fringe.

I was reluctant to contribute to the process by which people in the limelight are made to appear fraudulent, although I knew that it was the very nature of the extravagant claims made on their behalf by the publicity machines that made the result almost inevitable. So for many years I said little or nothing, although I was often annoyed by the misinformation that flew about. While I was stewing in discomfort over Professor Berg's letter, some of my most trusted friends suggested that it was time to set the record straight; and I decided to try, without precipitating one of those Welles-Mankiewicz hassles. These days, when the authorship of everything from the Bible to the latest cretinous effusion is considered suspect, there has arisen a foolish and uninformed skepticism. In such a climate, some may be all too eager to accept what I have related above; but I am not much more comfortable with that than I am with the indiscriminate attribution of nearly everything according to the auteur theory. It might be worth recalling that when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences belatedly gave its award for music to the composers of the score for LIMELIGHT, the three Oscars went to Charles Chaplin, Raymond Rasch, and Larry Russell.

City skyline

Chaplin's sketch of "Earnest David" Raksin.

Thinking about my time with Charlie, I realize that at some time or other in my young life I must have done something exceptionally right to have been blessed with such good fortune. I cannot imagine a more auspicious and inspiring way of beginning a career in film music than working with an artist - and man - of his caliber; not only were we doing something worth doing, and in style, but the experience itself was unique. Most days we went to lunch at Musso and Frank's, a nearby restaurant that is to this day one of my favorites. Charlie, Henry Bergman (who appeared in many Chaplin films; in MODERN TIMES he is the portly gentleman who gives Charlie and Paulette jobs in his cafe), Carter de Haven, Sr. (who had been a famous actor, and was the father of actress Gloria de Haven), and I would travel in splendor in Charlie's limousine. We always sat in the same corner table in the back room and had the same rather bored waiter. Almost anyone else would have been elated at the prospect of serving an artist of such eminence, but this one was onto all of Charlie's tricks and affected to be unaffected by them. But I loved every minute of it.

Charlie had certain little songs with which he would order his lunch, and we learned to sing them along with him. One of them, to the tune of “I Want a Lassie,” went: “I want a curry; A ricy, spicy curry, With a dish of chutney on the side!” Another, to the melody of “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” went: “An I-rish Stew, with veg-e-ta-bles…!” All were performed with gusto. Diners who were startled by the sudden outbursts from the corner table seemed to be quickly mollified at the thought of enlivening their dinner conversations with accounts of their luncheon entertainment.

The long hours we spent in the projection room were even nuttier. When we got stir crazy from concentrating we would often let off steam by doing acting improvisations - the crazier the better. Just about anything could set us off, and Charlie used to say, “You're a born actor.” (This might have helped to explain things to some of my colleagues who were later moved by some of my music to wonder what I was doing in their business.) Charlie intended to do a film about the Haymarket riots, which took place in Chicago in 1886; it would have been a drama about a shameful period in American labor history, and I was going to play a man named Louis Lingg, who was jailed and, according to Charlie, was murdered there. Another film which would have provided him with a role made for his talent was about Napoleon, and he wanted me to play the writer Stendhal. I am willing to concede that the world has been somewhat more deprived by not seeing him in his role than by not seeing me in mine.

There were also diversions, dinners, visits to Charlie's house on Cove Way in Beverly Hills, where he had a projection room and an organ which we both played. He showed me a Burmese gong made of beaten brass shaped like an enormous jar; on its pedestal, it was taller than we were. I got him to lean against it, then walloped it with the wooden log which was used as a mallet - and Charlie went flying, from the strong vibrations. I read him a laudatory passage from a book by Elie Faure; he remained silent, and I said, "Isn't it amazing for a man to live to hear such things about himself!

”One weekend Charlie, Henry, and I boarded the Chaplin yacht, a sixty-five-foot motor cruiser called Panacea, where his captain, a tall Scandinavian named Andy, and his Japanese chef, George, awaited us. And off we sailed to Catalina Island, where we anchored off White’s landing. Charlie and I dived off the stern and swam for a while, after which we enjoyed the first of several sumptuous meals, on the aft deck. As twilight fell, Charlie played his accordion and generously offered me a turn at it. According to my notes, I must have done a bit too well, for Charlie was annoyed with me. Next day, Andy broke out the fishing gear, and within half an hour Charlie had hooked what must have been an enormous fish. We never did get to see it, but it was so big that later, when the tide was running in, and the bow of the yacht would normally have leaned into the tide, this fish kept the stern facing into the current. All of this was carefully observed by a ship named Velero III, which belonged to an oil man named Allan Hancock and was used for the study of marine biology. Charlie stayed with that fish - or whatever it was - for nearly nine hours and refused to let anyone else touch the rod until, as twilight came on, the line broke. This persistence was, I later realized, another side of the perfectionism with which he was obsessed.

Somewhere, in those days, there must have been a travel agent who served international celebrities and who worked from a map on which there must have been a magnetic pushpin indicating the southeast corner of Sunset and La Brea in Hollywood. (There is, of course, a much simpler and more logical explanation for the number of famous people who visited the studio: the fascination exerted by that extraordinary man.) Among the guests who came to be entertained in the projection room and for lunch were directors King Vidor, Rouben Mamoulian, and Harry D'Arrast; the documentarian Pare Lorentz; writers Marc Connelly and Alexander Woollcott; and a number of performers, including the British actress Constance Collier, who, after watching us fit music to a comedy scene, said, “I find this as bewildering as a football game.” To which I replied, "I had no idea we were so simple." This led Carter de Haven to take aim at me with, “When a man blows out his brains, and lives, he becomes a musician.” I turned to Charlie and found that he had assumed the attitude of an interlocutor in a vaudeville show, and was waiting for me to say something appropriately mean. I obliged with, “And if he dies, he becomes an actor.” Somewhere amid all of the carrying on I put Charlie's fedora on sideways and “did” Charlie doing Napoleon. He was mildly amused, but I was quite carried away and said to Miss Collier, “Isn't it a wonderful world where you can do this to a great man's hat!

”I loved to egg Charlie on, to provoke him into an improvisation - which was not too hard to do. And I especially enjoyed his fluent way with the argot of London costermongers, in which certain words are made to substitute for others with which they rhyme. I was listening to Charlie kidding with Alf Reeves one morning, and he said, “Oh, I'm all right, but my 'Obson's is givin' me trouble. I musta got me daisies wet.” Charlie liked to have me ask what all of that meant, but by then I had already learned from him that 'Obson's was cockney for HOBSON'S CHOICE (a play), and hence stood in for “voice.” In the same way daisies stood for “daisy roots,” and meant “foots.” Another time he said to Mr. Reeves, “I can hardly keep the minces open." (For "mince pies" rhymes with “eyes.”) And, “Can't wait till I get home and lay the barnet ["barnet fair" equals "hair"] on the titwillow ["pillow"] and go bo-peep ["to sleep"]." He also had a favorite, very rude poem that began, “While sittin' one day by the Anna-Maria [“fire”], a-toastin' me plates o' meat [“feet”], I 'eard a knock on the Rory O'Moore [“door”] which made me old raspberry beat [“rasberry tart” equals “heart”].

”On a more sober note - too sober, as it turned out - my old friend Oscar Levant, who was a member of the circle with which I ran in my spare time, told me one day that Arnold Schoenberg, with whom he was studying, was eager to meet Chaplin. I spoke to Charlie at once, and it was arranged for Schoenberg to visit the studio a few days later. The great composer appeared with Mrs. Schoenberg for the meeting. I greeted them at the gate and took them into the projection room, where I introduced them to Charlie. In no time at all it was evident that the conversation which ensued was heading for a stalemate. Schoenberg, with his strong sense of his own eminence and his intellectual rigor, seemed baffled by the disparity between Chaplin's preeminent position as a film artist and his casual urbanity. It was disconcerting for Schoenberg to find that the cinematic genius he admired so much did not affect the serious demeanor which is in some cultures the perquisite of greatness. And although Charlie was on his best gracious-host behavior, the feeling soon grew awkward and painful, and it was with a sense of relief that I saw the visit end.

City skyline

Charlie Chaplin, Gertrude and Arnold Schoenberg and David Raksin at the United Artists studio in 1935. Years later, Raksin became a student of Schoenberg's.

For a brief time, when Charlie was called away to attend to some studio business, I was left to entertain the Schoenbergs, and while we were talking music I summoned up the courage to ask him whether he would consider accepting me as a student. He responded that he would want to see some of my music first, and we left it at that. (It was only after several years had passed, during which time I had not felt up to approaching him again, that Oscar Levant said that “the Old Man” had been asking about me; this time I went to see him, and he accepted me.) After the Schoenbergs left, Charlie said to me, "You were curiously chaste…I tried to explain that the irreverent schoolboy was, finally, somewhat awed, but gave up in embarrassment.

Chaplin was actually an admirer of fine concert music. In our projection room there was a pretty good phonograph, and he had brought some of his recordings in from home. These included a Symphony in D by Mozart (I cannot remember whether it was the Paris, K. 297, or the Haffner, K. 385, but I think the conductor was Thomas Beecham); also, Prometheus, by Scriabin (Stokowski's recording); Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms (with the composer conducting, I believe); the First Symphony of “Szostakowicz” (I think I copied that spelling from the label of the album, and the recording was probably the one by Stokowski with the Philadelphia Orchestra); a Balinese gamelan recording; and finally, a recording of Prokofiev's Third Piano Concerto (with Piero Coppola conducting the London Symphony and the composer as soloist). This last piece figured in a practical joke that says something disconcerting about the brashness with which I sometimes behaved, as well as the almost fatherly tolerance with which Charlie put up with my peccadillos.

Charlie had a portable tape recorder. (I believe it is the same one visible in some of the photographs taken when the two of us were reminiscing about the work on Modern Times on the day in 1952 before he left to live in Europe.) Occasionally he would play something back for me that he had hummed into the machine, and he liked to tell his guests that he used it so as not to lose some good idea that might come to him when I was not around to write it down. I think that this irritated me because the way in which he said it was outside the scope of our bargain—it seemed to reduce me to the flunky I had no intention of being. One morning, when he was late getting to the studio and I had no sketches to clean up, I put some bits and pieces of the recorded works on tape by recording them from the phonograph. Naturally, this would have to be the day that Charlie turned up with his wife Paulette (5) and their guest - H. G. Wells, no less. As expected, at one point he delivered his little spiel about the magic machine and ended by saying, "Let's see what's on the tape," and turning it on at full volume. With which, out blasted the second theme of the first movement of the Prokofiev Third Piano Concerto—and for a moment I thought that this was going to be the end of me. But everybody else thought it was funny, which seemed to help Charlie past a bad moment. (Today, I think I deserved a swift kick, but I am just as happy that I never got it.)

If I do not have my events mixed up, that was also the day we took Wells over to the recording session after lunch. As we were leaving the projection room, Wells, who had apparently been hearing about me from Charlie, turned and said, “Red… very red, I'm told.” While I stood there agape over the idea that this futurist should find my politics other than quaint, that beautiful young woman, Paulette, said in her best eager voice, “Oh, yes!” And Wells, in the manner of a farceur delivering an exit line, said, “Ah… a nice, old-fashioned color,” and swept out the doorway.

The recording sessions were a unique combination of working time and social event. Charlie was at his best, in his most elegant finery, sitting near the podium, listening and carrying on, sometimes conducting a bit, and generally charming everyone with his antics. He was delighted with the way the score was turning out, and his euphoria was contagious. Al Newan liked to record at night, when the rest of the United Artists studio was shut down. Since the stage was soundproof, this could not have been because of a need to avoid the distraction of daytime activities. After a while, I realized that there is a quality of isolation which those of us who work at night experience, a psychological remoteness that provides blessed relief from the clamor of everyday banality, and that this was what Newman was after. And when, after three or four hours of intense concentration, an intermission was called, the entire orchestra of about sixty-five, the sound crew, and the rest of us would adjourn to an adjacent stage where tables had been set up and a supper was served in grand style by the staff of the best caterers in town, the Vendome. This period of congeniality must have been very expensive - supper for about eighty-five, five nights a week for several weeks—but it was surely worth it, for it helped to sustain the feeling that something special was afoot, something elegant and worth the effort.

Eddie Powell and I shared a problem which the others were spared. When the recording sessions were over, the musicians and the sound crew went off to get some rest, to be ready for the next evening's work. But Eddie and I had to keep one jump ahead of the copyists and the orchestra, so we would usually resume work on the next round of orchestrations when everyone else had gone home. Since this went on and on, after a while we were both ready to be carted away from sheer exhaustion. One day Al Newman said to me, “You look sick. Why don't you take the night off - skip the recording.” I must have been pretty well worn out to agree to miss the session, but it was either that or collapse. So I went off to dinner with a friend and then back to my apartment to listen to some music - and embarrassed myself by falling asleep.

When I arrived at the studio next morning, I learned that Al and Charlie had had a fierce argument at the session; they too were operating on ragged nerves, and after one bad take Charlie had accused the players of “dogging it” - lying down on the job. At this, Newman, who at the best of times had a hair-trigger temper, had broken his baton and stalked off the stage, and was now refusing to work with Chaplin. This was put to me in a way that reveals a sleazy side of studio politics. Several of Sam Goldwyn's younger executives, who knew all the gossip, told me that I would be expected to take over and conduct the remaining sessions. I realized later that they would have enjoyed watching me struggle with the temptation offered by such an opportunity, believing that it was certain to supersede whatever loyalty I might feel toward Newman. But I said that if what they had told me was true, then Charlie was at fault and owed Al and the orchestra an apology, and that I could not agree to anything that would hurt Al or weaken his position. As it turned out, the United Artists people invoked Powell's contract with them and had him complete the sessions. With Eddie conducting, I did most of the remaining orchestration, and the recordings concluded in a rather sad and indeterminate spirit. Eddie and I thought that this was not the way to end things, so we gave a big party for the orchestra, complete with the best that the Vendome had to offer. But nothing could quite compensate for the fact that, as a result of my stiff-necked adherence to what I thought was right, Charlie and I became estranged, and we would not become friends again until many years later.

When, during the final recording session, we came at last to the ending of MODERN TIMES - the scene in which Charlie and the gamin (Paulette Goddard) once again dispossessed and having had to escape from the detectives, find themselves on the road at sunrise—I remembered something that Charlie had said when we were working to get the music just right. We had a guest that day, Boris Shumiatsky, the head of the Russian film industry. (I do not know whether I could have managed to be civil to him if I had known that he was the Soviet bureaucrat who had gone to such lengths to make Sergei Eisenstein's life miserable, to censure him, and to thwart his plans.) A note I wrote to myself that day contains no reference to Shumiatsky except to say that he was present. But it does juxtapose my own naivete with Charlie's more wordly outlook:

So now the film ends on a beautiful note of hope, with conquerable worlds on the horizon, and we spent much time deliberating [as to] how the music should soar—but Charlie is a bit cynical about the future of his… hero and his gamin. “They'll probably get kicked in the pants again,” he says (as we watch them on the screen, trudging hopefully away into the dawn). And they probably will, and it will probably happen in his next film.

Charlie's next film was THE GREAT DICTATOR, in which he played a dual role: he was Hynkel, dictator of Tomania (a satiric figure modeled on Adolf Hitler), and also a Jewish barber. Paulette played Hannah, and in the story they all had their share of troubles. Meredith Willson worked with Charlie on the score. Busy with my own thriving career - I was now composing film scores on my own - I would still have a long way to go before Charlie and I would resume our friendship; but that is another story.

It seems odd to me now that I, who remember so much about our time together, should remember so little about the inconclusive way in which our association ended back in 1935. Charlie remained cordial; but he was offended that, having been caught in the cross fire between him and Newman, I had sided with Al. I guess he did not understand how hard that was for me to do. We parted without formalities.

The gap left in one's life by the departure of so powerful a personality, moreover one who has become so close a friend and mentor, can hardly be described without risking overstatement. I know that I must have felt the loss keenly; but there is no memory of pain or of mourning, which tells me that whatever residual unhappiness was not gradually dispelled by the diversions of work and the good life as lived in Southern California I somehow assimilated, as perhaps a lesson in “Life as a Mixed Blessing.”

Years later, when Charlie and I had again become friends - almost as casually as we had parted - the final vestiges of that knot of sadness dissolved away, leaving me with a treasure of incomparable beauty and richness - the memory of my time with Charlie Chaplin and our work together.

Notes

1. It is still there—now the A & M recording studio.

2. Author of Within the Law and The Trial of Mary Dugan.

3. Theodore Huff, "Chaplin as Composer," Films in Review (September 1950).

4. I will paraphrase from my reply to Professor Berg. 5. Paulette Goddard, then Mrs. Chaplin, who played the gamin in Modern Times.