Alan Rawsthorne 1905-1971

The recent Silva Screen issue, 'The Ladykillers' (2) , reviewed in this issue, provides us with a much needed, tangible musical reference with which to measure Rawsthorne's writing for films in the context of his overall output. The three examples on this CD amply demonstrate the consistency of his style and quality when writing for the genre. We are immediately conscious of how admirably his distinctive voice is suited to the dramatic requirements of film. John McCabe has offered an insight into why this might be when he writes that "one of the greatest fascinations" of Rawsthorne's music derives from " ... the sense of profound undercurrents of emotion disguised by the elegant surface of the music, bursting out into forceful expressions on occasions The dramatic character which this reveals is a prevailing characteristic of his music: his juvenile writings disclose that his predilection for drama was established at an early stage. When writing for films the undercurrents which exist beneath the

It is a curious cultural world. If Alan Rawsthorne had written a concert piece playing twenty minutes and forty seconds, its first public performance would have been a major event, not only from the musical, but also from the journalistic standpoint. But since he wrote a film score of that length instead, the cultural press, musical or general, has not so much as noticed its existence. The film itself, Adrian de Potier’s and Basil Wright’s ‘The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci ’, has naturally been discussed in great and enthusiastic detail; and since films are reviewed by film critics, it seems unreasonable to complain that the music went by the journalistic board. But as soon as we think in elementary terms of value rather than in conventional terms of cultural departments, the situation proves absurd. After all, however excellent the film may be, the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci have been there before and a priori a cinematic exhibition or demonstration of them cannot be a work of art. On the other hand, it

When I tell relatives, friends or colleagues that I have been reconstructing old film scores, a polite if somewhat blank expression usually passes over their faces. I am sure they are conjuring up images of scissors and sellotape, and although I do use such things occasionally, they are not pivotal to my endeavours. What I do requires much more than pencil and rubber and a cassette machine, since what I am involved in is a series of extended aural tests.

Reviews

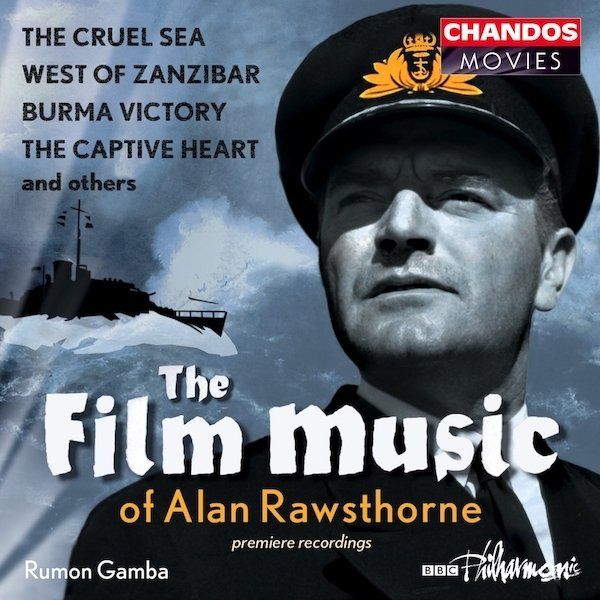

This representative selection of film music by Alan Rawsthorne ranges from war epics such as The Cruel Sea and Burma Victory to melodramas such as Uncle Silas and Saraband for Dead Lovers. However, arguably the most memorable tracks on the CD do not come from such powerful statements: the haunting waltz from Uncle Silas is a delight with its Prokofiev-like shifts of key and the graceful and charming Three Dances from The Dancing Fleece presage (and indeed outshine) the composer's 1955 ballet Madame Chrysanthème.

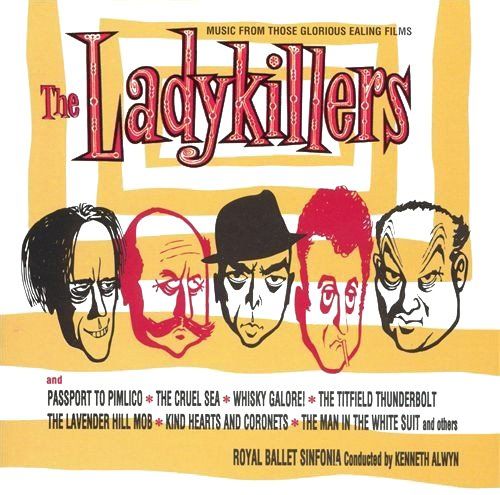

The recordings of the Royal Ballet Sinfonia, conducted by Kenneth Alwyn, playing music from a dozen Ealing films made between 1946 and 1956, feature three scores by Alan Rawsthorne — The Captive Heart (1946), Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948), and The Cruel Sea (1952). These are interspersed between other works by Frankel, Auric, Schurmann, Ireland, Tristram Cary and Ernest Irving. Another important name in the project is Philip Lane, who not only acted as Producer for the recording sessions, but, owing to the destruction of much of the original material, scored up the pieces from sound tracks by ear, or from a few surviving sketches. The results make 'The Ladykillers' a most attractive and enjoyable CD, all the music, except the John Ireland, receiving its premiere in this format.

The Rawsthorne Trust vies with the Finzi Trust in how much has been achieved for their respective composers in such a short time. Film royalties have continued to provide the funding for studio session after session. The mature Rawsthorne works have been recorded since the late 1990s principally by Naxos and latterly by Dutton. The linkage between the two is conductor David Lloyd-Jones who featured heavily and sympathetically on the Naxos recordings. He now conducts this assemblage of the rare and the familiar.