Rawsthorne’s Leonardo

Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 97, No. 1355 (Jan., 1956), p. 29

Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd.

It is a curious cultural world. If Alan Rawsthorne had written a concert piece playing twenty minutes and forty seconds, its first public performance would have been a major event, not only from the musical, but also from the journalistic standpoint. But since he wrote a film score of that length instead, the cultural press, musical or general, has not so much as noticed its existence. The film itself, Adrian de Potier’s and Basil Wright’s THE DRAWINGS OF LEONARDO DA VINCI, has naturally been discussed in great and enthusiastic detail; and since films are reviewed by film critics, it seems unreasonable to complain that the music went by the journalistic board. But as soon as we think in elementary terms of value rather than in conventional terms of cultural departments, the situation proves absurd. After all, however excellent the film may be, the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci have been there before and a priori a cinematic exhibition or demonstration of them cannot be a work of art. On the other hand, it so happens that Rawsthorne’s score is a work of art, and it has not been there before; moreover, concert programmes being what they are, it is likely to be more widely heard than any of his concert pieces.

The paradox is doubly symptomatic. For one thing, a terrifying section of our cultural world is more interested in unsatisfactory reproductions of old art than in satisfactory productions of new. For another, the unremitting drive towards cultural specialization can and does reach points where it has to sacrifice culture itself in order to continue with the business of specialization. In film-land, in particular, we tend to specialize frantically without asking ourselves the uncomfortable question what it really is we are so smugly specialistic about. In fact, the more competent a film critic is, the more safely can he be relied upon to examine the cinematic technicalities and the visual value of THE DRAWINGS OF LEONARDO DA VINCI, and to leave the music, the least important aspect, alone. Can such a film critic still be considered a cultural agent? It may be unfair to raise this question on the floor of a purely musical house; but where else can one raise it?

In his

Grove article on Rawsthorne, Colin Mason refers to "much incidental music for films and radio productions". Comparatively speaking, however, the composer’s film scores are few and far between. He started in 1937 with a short film for the Shell Unit. During the war he wrote THE CITY for the G.P.O. Film Unit and the series TANK TACTICS, UNITED STATES, and STREET FIGHTING, as well as what I think was his first feature film, BURMA VICTORY. In 1946 he composed his brilliant scores for THE CAPTIVE HEART and SCHOOL FOR SECRETS; more recent film scores are SARABAND FOR DEAD LOVERS (1948) which uses Corelli’s

Follia; PANDORA AND THE FLYING DUTCHMAN (1951) which unconsciously uses the minuet from Haydn’s last symphony; and the music for the Royal Command Performance film, WHERE NO VULTURES FLY (1951) which proceeds from C minor to C major like the film score now under review, with which it also shares Rawsthorne’s characteristic and unique brand of lyricism - chaste but uninhibited depth beyond sentimentality.

The total running time of LEONARDO is twenty-six minutes; in other words, there are only five minutes and twenty seconds without music. Michael Ayrton’s empty commentary, on the other hand, which Sir Laurence Olivier speaks as if it meant something, is well-nigh continuous, trying its best to make musical perception impossible and to reduce what is a thoroughly musical score to the status of an espresso bar’s background chants. In addition, both the Anvil recording and the Academy Cinema’s sound projection rob the instruments of colour and the texture of definition. In the circumstances, an evaluation of the score is not easy, but it is nevertheless possible. At some future date, perhaps, the film music critic will automatically be offered a score for inspection.

Rawsthorne must have written this piece more than a year ago, for though the film has only now reached the general public, it was shown at the National Film Theatre last year. This places the date of composition a little nearer to the symphony (1950), itself a landmark in the development of our age’s sonata thought. The thematic material does in fact show close affinities to that of the symphony’s first, slow and last movements, both in contour and in various highly characteristic details of rhythmic and harmonic structure. The ternary form may, moreover, be called ‘sonata’ despite the fact that there are six separate sections, if we are prepared to stretch the term so as to include any extended polythematic integration with an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. In any case, the entire structure grows from two subjects announced at the outset, which are very subtly related to each other. The texture, wholesomely lean and largely contrapuntal, clears the cinematic sound track of all the grease that it has accumulated since it was last cleaned by the American Leonard Bernstein in ON THE WATERFRONT. The instrumentation is a solo ensemble consisting, so far as I could make out, of flute, trumpet, piano and strings. It may be worth noting that the two instruments which the composer himself studied, the piano and the cello, seem to be the emotional principals of this chamber group.

The whole film score, Rawsthorne’s best to my knowledge, teems with unconventional and intensely imaginative exploitations of conventional schemes and devices. Thus, although fugatos are too often dead stretches, Rawsthorne’s developmental fugal exposition in the home tonality is an inspiration of the most original kind.

And the score’s relation to the picture? Do we, after all, agree with the film critic who would disregard this least important aspect? Yes and no. He thinks that the music is unimportant in itself, but absolutely necessary for the film. We think that the music is absolutely unnecessary, but of extreme importance in itself. And there, if I know my film directors, the matter will not rest.

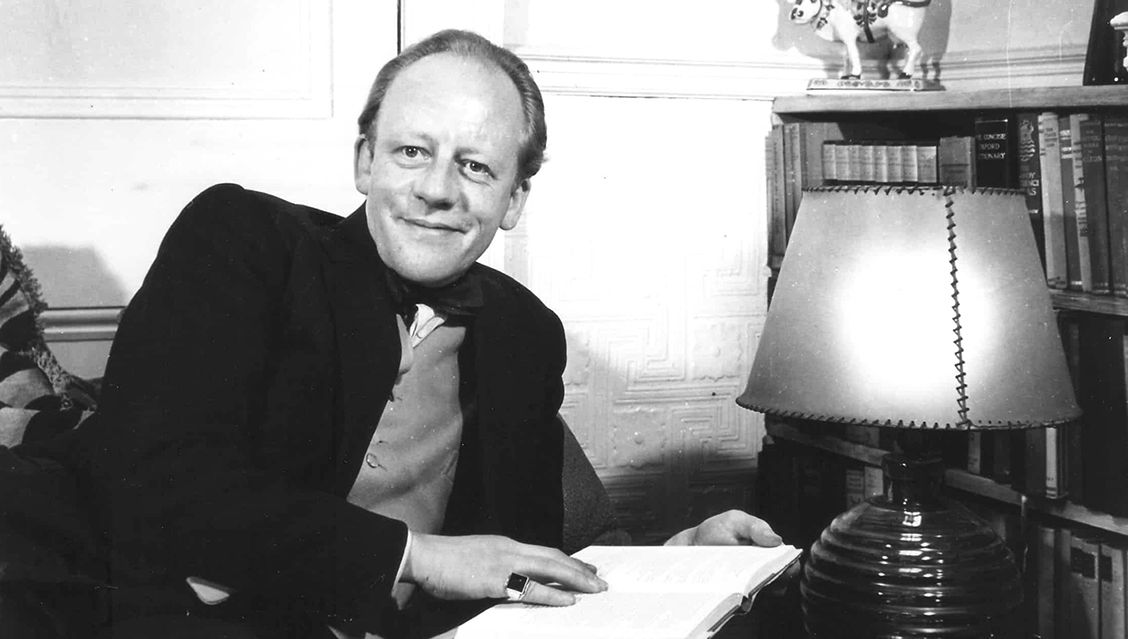

Editor's Note: The Vienna born critic Hans Keller (1919-1985) was arrested by the Gestapo during WW2 and following the death of his father escaped to England ca. 1938. Early on he was a freelance string-player in London, psychologist and writer and by the 1950s had established himself as a music ‘anti-critic.’ His involvement with film music originated from his special interest in psychology and contemporary mass media.