The piano occupied an important place in Rawsthorne's music. It is not surprising, then, that this should feature in his film scores. In both THE CAPTIVE HEART and THE MAN WHO NEVER WAS there are short, and rather tantalising, episodes in which characters in uniform improvise at the piano (always senior ranks, be it noted!). Was Gunner Rawsthorne 1123288, tempted to make a wry and tongue-in-cheek comment on the cliche of the composer in battle dress? He was released from his army 'captivity' on one or two occasions, after civilian colleagues secured leave for him to complete commissions, or to conduct. The term 'tantalising' is used because the piano episodes seem familiar, yet are elusive, like the clear memory a face to which one cannot put a name. The music is in the mould of the pieces which make up the composer's significant contribution to the piano literature. The ruminative and improvisatory passages in Theme and Four Studies, found among the composer's manuscripts after his death, are perhaps the nearest match. The precise date of their composition is not known, but it is fairly certain that they were written in the forties, placing them comparatively close to THE CAPTIVE HEART of 1946.

Only Connect

Publication: The Creel, Volume 3, Number 5, Issue Number 12, Spring I998

Publisher: Alan Rawsthorne Society and The Rawsthorne Trust

Copyright © 1998, by The Rawsthorne Trust. All rights reserved.

Text reproduced by kind permission of the Rawsthorne Trust

Only Connect:

Alan Rawsthorne’s Film Music in Context

"The first essential of a good film composer is a talent for composing. Film music must be genuine music." Alan Rawsthorne (1)

The recent Silva Screen issue, 'The Ladykillers' (2) , reviewed in this issue, provides us with a much needed, tangible musical reference with which to measure Rawsthorne's writing for films in the context of his overall output. The three examples on this CD amply demonstrate the consistency of his style and quality when writing for the genre. We are immediately conscious of how admirably his distinctive voice is suited to the dramatic requirements of film. John McCabe has offered an insight into why this might be when he writes that "one of the greatest fascinations" of Rawsthorne's music derives from " ... the sense of profound undercurrents of emotion disguised by the elegant surface of the music, bursting out into forceful expressions on occasions. (3) The dramatic character which this reveals is a prevailing characteristic of his music: his juvenile writings disclose that his predilection for drama was established at an early stage. When writing for films the undercurrents which exist beneath the surface of the music find a natural place in the stratum which lies beneath the action on screen. Here drama and understatement coexist, as elsewhere in his music, to concentrate, but not usurp, the visual message. In some instances, understatement does take the form of that surface elegance of which John McCabe writes. This elegance is expressed as a refined sense of proportion, knowing when and how to apply music. This makes the overtly dramatic statement all the more telling when it is made.

Writing in the Symposium on the composer, edited by Alan Poulton, the late Hans Keller, an erudite and rigorous musicologist, supports the assertion of consistency when he writes of the film scores: "they [are] magnificent music — all of them, and however intricate and cogent their relation to the visual, they would lose absolutely nothing if that relation were lost, the experience of sheer musical substance, of a reality that can't be expressed any other way, would not only remain, but actually emphasise its own irreplaceability far more clearly than it could in the cinema ... Rawsthorne always wrote music in the first place, and film music, equally conscientiously and clearly, in the second." (4)

A quality of Rawsthorne the man, reflected in his music, is a tendency to economy of statement; he uses no more notes than are necessary to advance the course of a composition, make clear a structure or, in the present context, to support the action on the screen. By habit he was a reticent conversationalist, yet a studious listener and observer, and when moved to express himself he would do so trenchantly. Such acuity is essential when writing for film. He had an enviable ability to expose the essence of an argument, situation or problem; any badly-focussed and prolix discourse was in danger of being demolished by a well-aimed epigrammatic intervention. Keller, himself not tolerant of sloppy thinking, again recalled a germane instance of this quality at a critical stage of the Maggio Musicale's International Film Music Congress, held in Florence in 1950. In a complex debate, which centred on what exactly made a good film composer, Rawsthorne turned to Keller and murmured: "Has anybody yet said that what you need for a film composer is a composer?". (5)

With characteristic pragmatism Rawsthorne reminds us that the title music is "probably the only music your audience will hear conscientiously" and is a brief opportunity "to establish the mood of the ensuing drama." (6) The title music of The Cruel Sea and The Captive Heart immediately establishes that the composer is Rawsthorne, and within the compass of a few bars the dramatic portent of what is to follow. The composer's use of a device for calling the audience to attention is common to cinema and concert hall. The Overture for Farnham, the opening movement of the Suite for Brass Band, the 'Sarabande' of the Recorder Suite and the opening of the Viola Sonata are clearly from the same stable as the title music for The Captive Heart and The Cruel Sea. All share an arresting blend of bitter-sweet harmony and the rhythmic fingerprint of dotted note patterns, which look back to the baroque era. The long opening sequence of The Captive Heart — the basis for 'Prisoners' March' — is an exemplary demonstration of the way the composer develops his basic materials, here used initially to set the scene and mood. In the 'Prisoners' March' the contiguous development of the opening dramatic motif portrays the mood of the dejection, the weariness and the impending fate of the silent column of soldiers as they shuffle into captivity. This is a seamless episode, made so not by mere continuity, but through an innate dramatic commentary, one derived from the skillful application of motivic development.

Rawsthorne was given cause to consider the nature of the unobtrusive quality of his writing for films. He related in a BBC broadcast that a friend had been surprised to learn that he had written the score for Tank Tactics (Army Film Unit, 1942). The friend commented that "he hadn't noticed that there was music in the film at all." Rawsthorne admitted that " ... at first this seemed a little damping and I prepared to go back to my job in the Quartermaster's stores in a chastened mood. But then I thought that perhaps it wasn't so discouraging after all and that the music might have been fulfiling its purpose better unobserved than if it had called attention to itself [by being] music that was directly suggested by tanks — the sort of noise they make and the way they move about." Whilst, once again, this demonstrates the composer's judicious self-effacement, of greater significance is his rejection of the facile and obvious.

Whilst Hans Keller contends that Rawsthorne's film music is capable of separate existence, qua music, the majority of his writing is so well integrated with and at the service of the drama, that it provides almost no ready-made set pieces capable of being extracted for concert performance. Prior to the recent reconstructions from the scores of The Cruel Sea and Saraband for Dead Lovers, only 'Prisoners' March' had been published for independent performance. To make this possible, a small amount of reworking was needed, which Rawsthorne explains in a note on the title page of the manuscript, "This March is not taken from the film, but is based on music to the film." Rawsthorne took essential components from the opening titles and, now removed from the need to accompany the visual element and the tyranny of the stopwatch, he moulds them into a cogent structure, which eschews a triumphant concert ending, opting for dramatic integrity he leaves the prisoners to march into the distance to one of his favourite markings, a niente.

The extracts recorded in 'The Ladykillers' CD all accompany scenes devoid of dialogue, so the composer grasps the rare mood-setting opportunities, of which he has written. The success of this may be judged by the vividness with which the screen images are recalled when the music is heard in isolation. In the case of the 'Carnival' from Saraband for Dead Lovers, this is most potent. The chaos, tumult of the revellers, terror and grotesqueries of the scene which it accompanies were, for me, made immediate. Furthermore, shorn of the background clamour of the mob, it was possible to appreciate the subtleties of the scoring, sounds not reproducible from the celluloid itself. There is other music from that film which deserves similar treatment, not least the sonorous passages which are derived from the baroque sequence `Folies d'Espagne'. A recollection of this was to emerge as the main theme of the slow movement of the Concerto for String Orchestra, a distant and unconscious echo of the recently completed film score.

The piano was to make the briefest of appearances in the title music written for Lease of Life (1954). Stylistically this episode shares some of the characteristics of the Second Piano Concerto of 1951. The piano part —performed by Irene Kohler — is in the robust bravura style of some of the writing of the concerto, and there is also an echo of the prominent trumpet obbligato which features in the last movement of the same work. These are mere decorations to the two main thematic components, one unique and the other an iteration of the opening theme of the last movement of the Concerto for String Orchestra. The effect is that of a collage and, as an entity, not convincing. Its function as an exposition becomes clear as Rawsthorne makes subtle use of the basic materials in the progress of the drama. This is not amongst the best of his film scores, one in which only eight minutes of original music is used. Rawsthorne was, however, to provide convincing and atmospheric scores for his last two feature films, The Man Who Never Was (1955) and Floods of Fear (1958).

Rawsthorne left very few compositional sketches or evidence of incomplete or abandoned works when he died. The archive of unpublished works leads one to question whether Rawsthorne did dip into a bottom drawer collection of sketches and pieces withheld from publication, to provide material for films. The keyboard player Alan Cuckston, when searching the Rawsthorne Archive for pieces to include in a recording of piano, song and violin music, unearthed, `Pierrette' — Valse Caprice for violin and piano, written in 1934 for Rawsthorne's first wife, Jessie Hinchliffe. It was only after the recording had been made that I became aware that it had been recycled in the score for Uncle Silas, 1947. There it appears, dressed in more adventurous harmonic clothes, to provide music for a ballroom scene. This music is characteristic neither of the music elsewhere in the film nor of his compositional style and language at time the film was made — the year the Concerto for Oboe and Strings was written. Nevertheless it finds a fitting place in the film.

Rawsthorne's earliest and latest film scores were for documentaries. The Rawsthorne Society arranged a showing of two of these for its members at the British Film Institute in May 1996, The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci (1953) and The Dancing Fleece (1950). Each film runs for approximately twenty minutes with music continuous throughout.

The first is scored for string quartet, flute, trumpet and piano. The date of composition is close to that of the Symphony No.1 — 1950, and has close thematic affinities with the first, slow and last movements of that work. The overall impression of the production was one of immense richness, perhaps over-richness. The images are accompanied by a near continuous narrative by Michael Ayrton, delivered by C. Day Lewis and Laurence Olivier. The effect of this is to detract from the musical perception. Narrative and images would make a satisfying entity without the addition of music.

Hans Keller considered this to be the best of Rawsthorne's film scores when assessing it in 1956, furthermore it was his view that the music was of extreme importance in itself , but absolutely unneccessary to the film. (7)

The unusual and effective combination of instruments is a reminder that Rawsthorne was a composer skilled in the writing for chamber combinations. Music from the 'Leonardo' score was later absorbed into a chamber work for another interesting combination, the Concerto for Ten Instruments of 1961.

The Dancing Fleece, a commercial depicting the production of wool, drew from Rawsthorne a twenty minute ballet score. The eminently danceable music foreshadows the forty minute, one act ballet, Madame Chrysantheme, which was first performed by the Sadler's Wells Ballet in 1955.

The destruction of most of the film music manuscripts is to be deplored; Rawsthorne was not the only composer to fall victim to the wanton despoliation which accompanied the disbandment of Ealing Studios. There is more material which, with time, may be given a public hearing. The brilliant reconstructions by Rawsthorne's pupil and collaborator Gerard Schurmann, and Philip Lane, assure us of the viability of such further projects, and of the guaranteed quality of the results. Further explorations of this material can be wholly justified as worthy of pursuit if we have in mind Hans Keller's critical assurance that "Rawsthorne always wrote music in the first place, and film music, equally conscientiously and clearly, in the second...", and Rawsthorne's belief that "Film music must be genuine music."

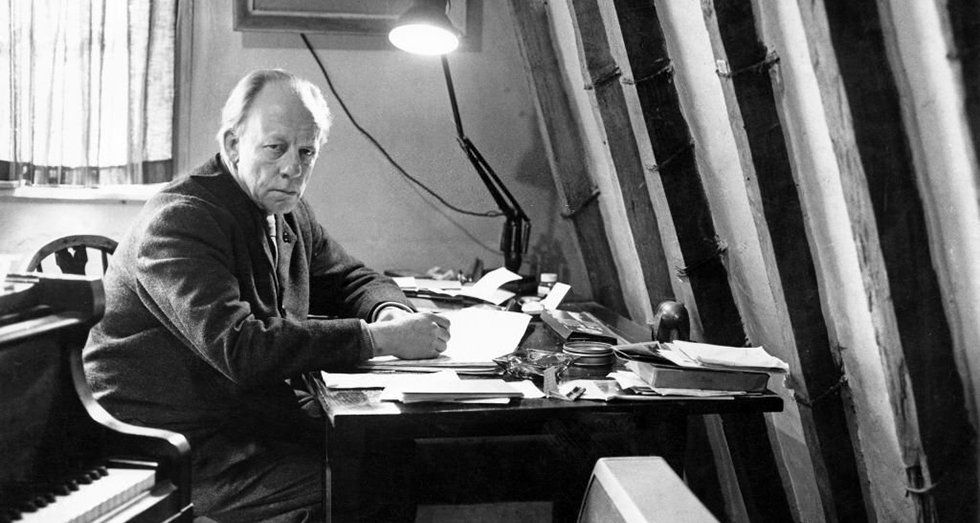

Photos

Alan Rawsthorne at his home in Little Sampford, Essex, 28th March 1966. (Photo by Erich Auerbach)

Alan Rawsthorne in uniform, with Muir Mathieson and William Alwyn, at the recording session of Alwyn's music for

The True Glory, Scala Theatre, London 1942.

Notes

- 'The Celluloid Plays a Tune' from Twenty British Composers ed. Peter Dickinson, Chester, 1975.

- The Ladykillers - music from those glorious Ealing Films, Silva Screen Records Ltd FILMCD 177

- 'Rawsthorne's Greatest Achievement?', The Creel VoI.l No.3 Autumn 1990

- Alan Rawsthorne; Essays on the Music, Vol. 3, Ed. Alan Poulton, Bravura Publications, Hindhead 1986

- Keller/Poulton, op. cit.

- Peter Dickinson, op. cit.

- See Film Music: Rawsthorne's 'Leonardo' The Musical Times, January 1956

Rawsthorne Film Scores

1930s

Power Unit c. 1937

The City 1939

Cargo for Ardrossan 1939

Shell Film Unit (GB)

GPO Film Unit

Realist Films (GB)

1940s

Street Fighting 1942

Tank Tactics 1942

USA The Land & the People 1945

Burma Victory 1945

Broken Dykes 1945

The Captive Heart 1946

School for Secrets 1946

Uncle Silas 1947

Saraband for Dead Lovers 1948

x - 100 1948

Army Film Unit (MOI)

Army Film Unit (MOI)

War Office

Army Film Unit

Min. of Information

Ealing Studios

Two Cities

Two Cities

Ealing Studios

Shell Mex G

1950s

The Dancing Fleece 1950

Pandora & the Flying Dutchman 1950

The Waters of Time 1951

Where No Vultures Fly 1951

The Cruel Sea 1952

The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci 1953

West of Zanzibar 1953

Lease of Life 1954

The Man Who Never Was 1955

The Legend of the Good Beasts 1956

Floods of Fear 1958

The Port of London 1959

Crown Film Unit

Romulus Films

Intl. Realist Ltd.

Ealing Studios

Ealing Studios

Leonardo Film C'tee

Ealing Studios

Ealing Studios

Sumar Films

Bear Films (GB)

Rank

Greenpark

1960s

Sweat Without Tears 1960

Messenger of the Mountains 1964

Kuwait Oil Company

Countryman Films