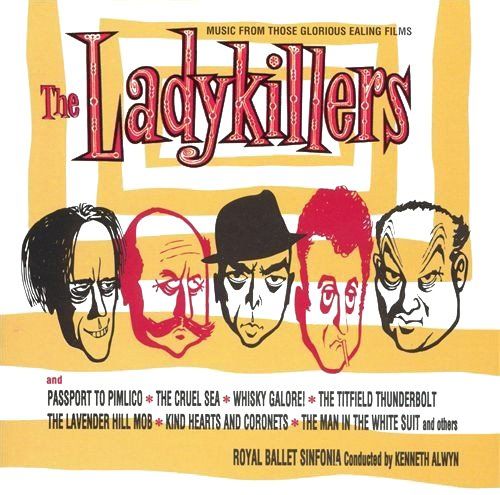

The Ladykillers

Label: Silva Screen

Catalogue No: FILMCD 177

Release Date: 1997

Total Duration: 60:36

Royal Ballet Sinfonia cunducted by Kenneth Alwyn

The Ladykillers - Music from Those Glorious Ealing Films

The recordings of the Royal Ballet Sinfonia, conducted by Kenneth Alwyn, playing music from a dozen Ealing films made between 1946 and 1956, feature three scores by Alan Rawsthorne — The Captive Heart (1946), Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948), and The Cruel Sea (1952). These are interspersed between other works by Frankel, Auric, Schurmann, Ireland, Tristram Cary and Ernest Irving. Another important name in the project is Philip Lane, who not only acted as Producer for the recording sessions, but, owing to the destruction of much of the original material, scored up the pieces from sound tracks by ear, or from a few surviving sketches. The results make 'The Ladykillers' a most attractive and enjoyable CD, all the music, except the John Ireland, receiving its premiere in this format.

Our principal focus of interest in this journal is the three short extracts of Rawsthorne's work. They must serve as a taster for what I hope will one day be an entire record selected from his film scores, about whose quality such a distinguished authority as Hans Keller has left us in no doubt, and upon which wider subject you will find another article in this issue of The Creel, from the pen of John Belcher.

Of the three Ealing pictures featured on this CD, the earliest is The Captive Heart. The composer himself made a version of The Prisoners' March, as here played. There had apparently been plans for Decca to issue a recording of it, under Muir Matheson, in the late 'forties, but this came to nothing. It is a locus classicus of all that we identify in the composer's style at this time: the lean two-part textures with their melo/bass tension, the Hindmithian neo-baroque use of trills in the principle line, the rather melancholy minor key tendency, the orchestral means economic and effective (this 'March' drawing to a close with a solo clarinet and solitary drum). The original movie is spoken of as the finest POW film ever made. Certainly, Rawsthorne's contributions are most distinguished, and help to provide the atmosphere so well summarised in David Wishart's sleeve notes. (He sums up each plot, and every musical excerpt, most succinctly) — "there is a solemn ennobling here — symphonic laurels for the valiantly defeated."

Responsibility for the arranging and orchestration of the Saraband for Dead Lovers track here belongs to Rawsthorne's pupil, Gerard Schurmann. The composer took, as the principal musical inspiration for a picture set in the court of the Elector of Hanover in the late 17th century, the popular Renaissance ground-bass known as 'La Follia', which attracted composers from Corelli to Rachmaninov. The connection of Corelli with the Hanovarian court has been questioned. But the Sarabande rhythm favoured by Rawsthorne here was much employed by Handel, whose relationship with the elector is well-known. Indeed, Rawsthorne's evocation of the Baroque concentrates on aspects other than the bass: the altering major and minor 7th of B minor are sounded over a pedal-point whilst melodic motifs echo Corelli's Violin Sonata. (La Follia's chord sequences are heard in a vocal version in the course of the film score). (1) (Schurmann's own score for The Man in the Sky also features on this disc. Rawsthorne 'flavours' surface here and there, as in the reflective intermezzo, and his decorative baroque-style virtuoso `Divisions' for trumpet "heralding the sheer exuberance of flying" are reminiscent of those in Saraband for Dead Lovers).

It is difficult to understand Ealing's choice of this tale involving the dynastic aspirations and machinations of a German prince, other than as a romantic vehicle for Joan Greenwood and Stewart Granger, who enact an illicit relationship. Certainly it would have served to remind us how German history intertwined with our own.

One of its most memorable juxtapositions of music and cinematic image occurs in the selection here recorded. For Greenwood to keep her tryst with Granger she must run the gauntlet of a street carnival. It is a kind of nightmarish Freudian masquerade, a rapid succession of conjurers, fire-eaters, grotesques and circus freaks in orgiastic colours (this was Ealing's first Technicolor venture). There is rhythmic asymmetry, and much percussion, which culminates in her hysterical pounding on his door. Curiously, this new performance, for all its pristine clarity, does not seem to have, in my memory, quite the exciting edge of the original track, where it was conducted by Ernest Irving.

The Rawsthorne idiom was an inspired choice for underlining the fate of these doomed lovers, and generally works well in brief phrases. Occasionally, a little meanly truncated in the cutting, they are sometimes terminated in the original score, let it be said, with a rather mannered cliché.

By contrast, the dynamism of his highly energised rhythmic writing, as in the Carnival episode, is extremely exciting. A similar moment occurs in The Captive Heart, as the prisoners greet the arrival of their Red Cross parcels. There are even episodes of piano playing mimed by the actor Derek Bond, both in the domestic drawing-room and in the prisoners' camp hut, which seem to bring us most personally in touch with AR himself. Suddenly one is aware of an almost tangible presence, as if he sits improvising at the keyboard in his most inimitable style. (The player was actually Irene Kohler).

With The Cruel Sea we reach the latest of the films on this disc to feature a Rawsthorne score, and presumably one of the last conducted by Ernest Irving (1878-1953). There can be no underestimating of the importance of Irving in the history of British film music. He it was who encouraged Georges Auric, the only French composer heard on this record, to go in for film composition. I imagine he brought in his own contemporary, John Ireland, too, from whose Overlanders music we also hear an excerpt (Alan Rawsthorne also assisted in this score). Irving gave commissions to the youngest heard here, Tristram Cary, (b.1925), whose Ladykillers music is presented with its original jubilant finale restored. Irving's own score for Whisky Galore reveals an infectious rhythmic propulsion in the Scottish taste; for Kind Hearts and Coronets he borrows from Mozart (as does Auric, but comically, in The Titfield Thunderbolt).

It is not surprising to learn that The Cruel Sea, from its repeated TV screenings around the world, is Rawsthorne's biggest earner in terms of royalties. The story of the corvette Compass Rose in wartime convoy has something of an epic Greek quality. Its concentration on an almost sacred all-male world, with the David and Jonathan relationship of Captain and 'No.1', Jack Hawkins and Donald Sinden, seems also quintessentially British.

Rawsthorne's musical contributions are spare and always telling. One would love to know precisely what his brief was. Was he a free agent, judging the exact moment where his own work was needed? Or was it so many guineas a minute?

Philip Lane's selection of The Cruel Sea music presents Rawsthorne's admirably fashioned two principal subjects (indeed, they could almost be a symphony's first and second themes). These may be taken to represent the stoicism of the men 'doing their duty' in time of war, and in the face of the enemy, by contrast with their more tender humanity, their concern for their mates.

The fanfare-like opening motif, outlining the B flat minor triad in dotted rhythm, recurs at various points in the picture in several transpositions and transformations. The orchestration ranges from full orchestral brass, with prominent tuba, and harp glissandi, down to the characteristic solo woodwind voices of oboe and bassoon. Open fifths from the strings float out some reminiscence of a Debussy 'Nocturne', or La Mer. (What an influence on subsequent sea music that has been! — it can be heard too in Clifton Parker's fine score for Western Approaches, some years earlier than The Cruel Sea, though Parker does not have anything like Rawsthorne's individual sound).

Apart from the fascination of these Rawsthorne excerpts, the record also offers such delights as another remarkable musical invocation of a steam train to add to those of Villa-Lobos, Britten, Vivien Ellis, et. al., in the shape of Georges Auric's Titfield Thunderbolt. The delicious instrumentation and Gallic wit of the same composer's Passport to Pimlico, with its strutting quotations of French melody (Pimlico, is, after all, historically part of Burgundy!) reveal tinges of Poulenc, Auric's own exact contemporary.

Ben Frankel's

The Man in a White Suit reminds us of yet another fine composer of Rawsthorne's generation. His modern mechanistic rhythms communicate the clacking of the looms in Scottish textile factories with a telling clarity. My only slight cavil in listening to these film scores concerns certain sections of

The Ladykillers, where the music seems too literally to mimic the screen action, cartoon-like. This becomes slightly tiresome.

Alan Cuckston was born near Leeds and read Music at King's College, Cambridge, where he was a pupil of Thurston Dart. He successfully auditioned for the BBC as a keyboard soloist and joined the staff of the Music Department at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts at the University of Birmingham.

For the past twenty five years he has been a freelance player, with some specialisation in early keyboard instruments - harpsichord, organ and fortepiano. He has given concerts in many parts of Europe and North America and has toured as harpsichordist with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields and as organist with Pro Cantione Antigua.

Alan Cuckston has made recordings of an extensive repertoire of music, ranging from the middle ages to the present day. In recent years he has released harpsichord music by Handel, Rameau and Couperin on Naxos and the complete piano music of Alan Rawsthorne (also the complete music for violin and piano and a selection of songs) on Swinsty Records.

Notes

- Alan Cuckston accompanies Sandra Dugdale in a recording of this, 'Saraband', on Swinsty FEW 120 (Piano Music & Songs by Rawsthorne).

Publication: The Creel, Volume 3, Number 5, Issue Number 12, Spring I998

Publisher: Alan Rawsthorne Society and The Rawsthorne Trust

Copyright © 1998, by The Rawsthorne Trust. All rights reserved.

Text reproduced by kind permission of the Rawsthorne Trust