What Ever Happened to Great Movie Music

Originally published in High-Fidelity : July 1970

Copyright © High-Fidelity 1970. All rights reserved.

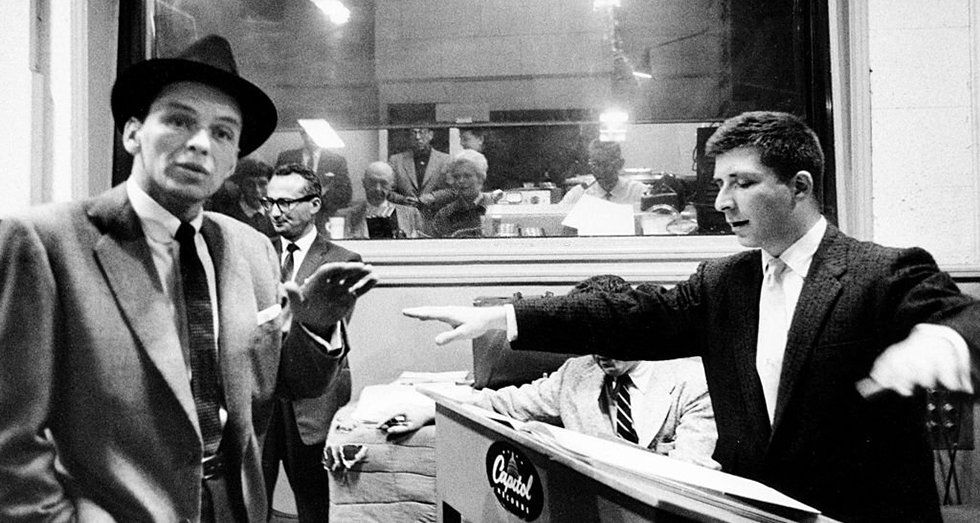

Photo: Frank Sinatra with Elmer Bernstein recording 'The Man with the Golden Arm'

The events of the past few years in the field of film scoring seem to indicate that any discussion on this great art may indeed have to be a historical summary at the end of its era of greatness. As a working film composer and an evolutionary product of the works of Aaron Copland, Bernard Herrmann, Max Steiner, Erich Korngold, Hugo Friedhofer, Franz Waxman, Alfred Newman, David Raksin, George Antheil, Miklos Rosza, Dimitri Tiomkin, and Bronislau Kaper, and a contemporary of Alex North, Jerry Goldsmith, Henry Mancini, Lalo Schifrin, and Andre Previn, I find it inconceivable that this sophisticated art has in such a short time degenerated into a bleakness of various electronic noises and generally futile attempts to “make the pop Top 40 charts.” Today the trend is most obviously to the non-score, the song form, and General Electric. It appears that the king is dead and the court jester has been installed in his place. Before we consider the causes of death, let us first proceed to an examination of the corpus while its remains are still with us.

Music is the art that begins where words and images leave off - which is what makes it so effective in films. Sonic vibrations set part of the body in motion and touch the listener in an almost purely visceral manner. Music can stimulate the greatest possible range of moods, shades, and fantasies. Also, it is an art that envelops the listener, who cannot escape it save by leaving the area. Unlike the written word or visual image, there is no need to intellectualize its existence. That its source is unseen and that it can enter and leave at almost imperceptible levels makes music an invaluable tool with which the skilled film composer can practice emotional seductions upon the viewer of a movie. Parenthetically, it is of interest to note that in the days of silent films David Wark Griffith used musicians to inspire his actors to passion on the set.

Some of us are old enough to remember the orchestras that accompanied the lavish first runs of silent films, or the inevitable pianists who created moods to help the neighborhood audiences hiss villains and applaud heroes. Many scores were composed and tailored to the films of their day, with written descriptions of the screen action so that the performer would know whether he was playing slow or fast enough to suit the image. The earliest piano scores for movies I know of - and which are still extant - were written for the films of Georges Méliès in the closing years of the nineteenth century. In these primitive scores, music was used to mimic the action on screen: fast music for fast action, lumbering music for lumbering action, low and menacing notes for the villain, trumpet-like themes for the hero, and so on. The music became a series of representative cliches rather than an emotional communication, and a whole set of conventions quickly grew up by which one could easily identify villain, hero, the chase, and love. Today one laughs at them, but in their heyday audiences looked forward to these conventionalized cliches.

It was quite natural, of course, that when sound came in audiences were more interested in hearing the voices of their favorite movie stars and musical performers. The earliest use of music in connection with non musical films seems to have been the filling of “dead spots” with some sort of sound. Today the results appear quite amusing - the music seems to drone on quite unrelated to the events in the picture. In this sense the lack of sophistication, integration, and skill is not unlike that of many contemporary motion pictures where the score functions merely to introduce popular material not often integrated into the film.

Max Steiner arrived in Hollywood in 1929. Very quickly his work educated the film colony to the possibilities of film music tailored to the needs of specific dramatic situations. Strange as all this may seem, it was in its time an original and thrilling concept. Steiner also pioneered musical authenticity. Nowadays we assume that a composer will research the music indigenous to the country in which a film story takes place. It is difficult then to remember how fresh and exciting was Steiner's attempt to create an Irish musical ambience for THE INFORMER.

During the following generation Hollywood scores, at least the best of them, developed into a sophisticated art form using sophisticated techniques. The techniques of course were not always apt. Take the leitmotif. The leitmotif - a specific theme continually used to identify a specific character, situation, or emotion - is a time-honored musico-dramatic device raised to great heights by the genius of Richard Wagner. Its application in film scoring is obvious, but unless used well it can become another boring and trite device. My own score for THE TEN COMMANDMENTS made extensive use of the leitmotif. This score is in many ways the least characteristic of my works as it was written while working under the close supervision of the producer, Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille believed the function of music in a motion picture to be an adjunctive story-telling device, with each character having a particular theme or motif to accompany his moments on screen. In THE TEN COMMANDMENTS, DeMille insisted upon identifying themes for Moses, Joshua, Ramses, Nefretiri, Lilia, Dathen. In addition, there were to be motifs for two opposing themes: the power of God and the force of evil. The motifs were heard whenever the characters were on screen and in cases where there was an interplay between two characters, a Wagnerian interweaving of the tunes was expected. Changes of mood created by the dramatic necessities of the story were accompanied mainly by changes of orchestral color. Thus when Moses is an infant in the bulrushes, his theme is performed by woodwind solo to a 6/8 lullaby accompaniment. Later, when he has become the prophet, his theme is announced by trumpets and horns in a martial tempo. And in this way one finds the score retelling the events on screen. This technique requires great skill in its execution to avoid extreme banality and is, I believe, one of the least attractive uses of film music since it serves merely to repeat what should be clearly evident in a good film. The leitmotif functions best in a film of epic proportions, for not many characters merit the grandeur of an accompanying musical theme. In other situations the constant repetition of a theme for a character becomes an unpardonable intrusion upon the dramatic integrity of the film. Besides, how many melodies have been created for films that one would want to hear twenty times in the course of ninety minutes?

Even more dangerous than the leitmotif device is the mono-thematic score. The single theme can designate a particular overriding emotion, as in Alfred Newman’s LOVE IS A MANY-SPLENDORED THING (85 percent of that score is based on one tune), or it can even identify a character, as in David Raksin’s eternal LAURA. A technique that can be - and nowadays usually is - a boring cliché had its classic expression in LAURA. The film portrayed a man falling in love with a ghost: The mystique was supplied by the insistence of the haunting melody. He could not escape it, it was everywhere. It was there when he was in Laura’s apartment. It was there when he turned on the record player. It was never absent from his thoughts. We may not remember what Laura was like, but we never forget that she was the music and in that music she has of course come into our lives to stay. In that instance, the music and its insistence was the most compelling feature of the film.

For me, film music functions best when it is able to deal with that which is implicit but not explicit in a scene. It can thus add to the film art rather than simply ape another element in it. Here is another example from my own work: IN MEN IN WAR one scene shows a group of soldiers walking through a Korean forest which they know to be mined. They are quite understandably terrified by the possibility of sudden death at every step. As I looked at that scene and considered what I wished to do musically, I thought of how many battles had been fought in the midst of beautiful country. As these men were making this walk their surroundings were a forest full of birds singing, leaves rustling, twigs snapping-sweet aural counterpoint that made the possibility of death even more terrible. I decided to emphasize this less obvious counter point in my music. While I called for an almost imperceptible tremolando in the basses, timpani, and bass drum, I had the cellos gently guide the wind through the leaves in delicate pianissimo glissandos and trills, the woodwinds play quick, disjointed birdlike calls, the xylophone and other percussion play staccato woodsy figures, and I gave any sustaining lines to the ominous-sounding bass flute or the bass clarinet. This approach served to deepen the terror of the scene as it added an interesting subliminal note to it.

One of the surprising attributes of the film score is its ability to speed up or slow down the action. In my early career I believed that the accompanying music must have a kinetic energy equal to that of the scene for which it is written. Cecil B. DeMille changed my mind about that. In the Exodus scene of THE TEN COMMANDMENTS there is the moment in which the Hebrews begin their march out of Egyptian bondage. DeMille used approximately 8,000 people in that scene, with the effect that the start of their march was passive and lumbering. The first music I wrote for the scene was a ponderous Hebraic march-like anthem. DeMille hated it. When I insisted that it had truly reflected the pace of the scene, he readily agreed, and stated that that was the trouble with it. If I would write music with a faster pace than that of the scene, the Hebrews would appear to move more brightly, the elation at their freedom would be more prominent. I was skeptical, but tried it. DeMille was right.

I remembered my lesson when I composed the score for THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN. The unhurried pace of the film as a whole was always a potential danger in a story that demanded tension and suspense. To help this situation I wrote the music in tempos always somewhat faster than those of the film’s, and made considerable use of vigorous rhythmic patterns as well as repeated sixteenth note figures. Again, I believe it worked.

The main body of a film composer’s work is done after the editing is completed, though in some instances the composer may be called in for conferences even before shooting begins. This would be necessary for instance where musical material must be included in the shooting of a film. When the film is finally assembled, the composer and the producer or director view the film together and begin their general discussion about the character and use of music. In most cases the composer is left to decide such fine points as where the music should begin and end. The music editor then writes a description of every action and word of dialogue in the scene accurate to one-tenth of a second. The composer usually works from these descriptions, but some composers prefer to have the film and a Movieola in their homes. Since film is a medium locked in time, the composer must learn to compose music that falls naturally within the time confines.

In the recording session, the film is projected as the musicians perform. There are various visual metronomic devices such as streamers and punches on the film to aid the conductor in his job of synchronizing the playing of the music to the action of the film. The final process is one in which music, sound, and dialogue are united into one sound track.

One of the many problems besetting the film composer is the rapidity with which a device that seems fresh in one film so quickly becomes commonplace. One reason for this is the tremendous exposure afforded by motion pictures. The concert hall composer is lucky to expose his work to perhaps two thousand people at a time. But films are seen (and heard) by upwards of fifty million. It is very difficult for a fresh musical idea to stay fresh long under these conditions. The bass flute solo, which could be used to engender terror only a few years ago, is now part of the everyday language of the film composer. The once effective romantic “piano concerto” style has become banal almost to the point of the comic. To many second-rate movie composers, this phenomenon is terrifying and sends them to frantic searches for “new sounds” - which are also soon exhausted.

Two innocent events in the early and middle Fifties. it seems to me, signaled the beginning of the end of the golden age of film music. The first of these was the extraordinary commercial success of the title song by Dimitri Tiomkin for the 1951 motion picture HIGH NOON. How fresh and exciting that main title seemed then! But the free advertising resulting from the song - not to mention the enormous money that the song itself made - led to an instant demand by movie producers for similar title songs in almost every picture that followed. Lyric writers were beset with such problems as selling titles like THE REVOLT OF MAMIE STOVER to music and the situation rapidly became ludicrous. But the commercial attitude has remained: To hell with the score - let’s get that title song on the charts!

The second event was the success of my own MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM in 1955, which was compounded by Henry Mancini's TV success with PETER GUNN. With the commercial bonanza of these “pop” sounds in two perfectly legitimate situations - my score was not a jazz score, but a score in which jazz elements were incorporated toward the end of creating specific atmosphere for that particular film - producers quickly began to transform film composing from a serious art into a pop art and more recently into pop garbage.

It is no secret that many title songs have made more money than the movies they came from. Movie companies suddenly became music publishing houses and recording firms so as not to allow any of the loot to slip by them. And in the process the serious composition of thoughtful film scores was given short shrift.

We live in times in which the soul must learn to live with the senseless killing of millions through out the world; with the necessity of the double lock; with the knowledge of where not to walk after dark. We have learned to accept the philosophy that no person in public life can ever tell the whole truth, and that the future might hold annihilation either through man’s brutishness or through his ecological selfishness. In such a world, art tends to become sensation, aesthetics becomes a belief that the way to protest brutality is to reflect it in art. In motion pictures we are treated to an onslaught of violence and sensation, without form, without art, and with out humanity. In this atmosphere the quality of film scores is being strangled by the search for effect, for “new sounds” without content and form on the part of the artist, and by avarice on the part of the producer. Today the once proud art of film scoring has turned into a sound, a sensation, or hopefully a hit. How ironic that in an era in which music enjoys its greatest popularity as an art, film producers are demonstrating the greatest ignorance of the use of music in films since the beginning of that medium’s history.