Muir Mathieson

Guild of British Film Editors Journal, No.46 Dec. 1975, pp 24-25

Copyright © 1975 Guild of British Film Editors

Obituary on Muir Mathieson, 1911–1975

Muir Mathieson - without a shadow of doubt the greatest name in the history of British film music, and arguably one of the most significant people in all film music - died on August 2nd 1975, aged only 64. His terminal illness was mercifully short. I had the pleasure of lunching with him and his charming wife Hermione at their lovely old house at Frieth very shortly before he died. I believe I knew him as well as any technician in this country; certainly our friendship had lasted for nearly forty years.

I cannot remember precisely the first time we collaborated. It was probably for some documentary made by the G.P.O. Film Unit - not an epic by the standards of motion pictures - but nevertheless a film for which Muir had persuaded William Alwyn, or Richard Addinsell, or Arnold Bax, or Ralph Vaughan Williams, or one of the great figures of music, to write a score for the five guineas or so which was the most that the Unit could afford.

This, I believe, was an aspect of Muir's contribution to films which had a greater importance even than his extraordinary skill in achieving the right mood and the right timing. A young man in those days, he could command the barefaced cheek to approach the mighty, and persuade them to work for this rather new, not terribly respectable, medium. Not only persuade them, but guide their somewhat hesitant hands into producing scores like William Walton's HENRY V, Vaughan Williams' 49th PARALLEL, Bax's MALTA G.C., and innumerable others. It is, I venture to say, entirely due to Muir's tact, perseverance and skill that British film music achieved a world-wide eminence in the forties and fifties.

He had an irascible, dominating personality. He would never suffer fools gladly. One did not argue with Muir. One either fought with him tooth and claw or one submitted to his dominance with as much grace as one could muster. The infuriating thing was that he was always right. Or, at least, nearly always! I remember getting what I thought was quite a good balance on the main titles of V.W.'s COASTAL COMMAND in the H.M.V. studios in Abbey Road. I thought it was quite good and, bless his heart, so did Muir. But V.W. wanted more trombones, so we re-balanced. But V.W. wanted still more . We ended up, literally, with only the trombone mike open. Muir and I thought it was terrible, but that was the way V.W. wanted it. And in the end it was V.W. who was right. However, this is not a eulogy on V.W.

And what fun we had with Malcolm Sargent, Ben Britten and Muir on INSTRUMENTS OF THE ORCHESTRA - the music now known as THE YOUNG PERSON'S GUIDE. Muir not only handled that masterpiece with all the skill it deserved, but he directed the film with an expertise which was pretty wonderful considering he had never directed so much as an insert before.

Talking of directing, I had the pleasure of being concerned with a series of twenty-four educational films called WE MAKE MUSIC. I say I was concerned with them. But Muir wrote and directed the lot. And he usually got over twenty minutes' screen time with-non-professional actors, albeit highly skilled musicians, in one and a half days. These films are still widely shown throughout the world and form a presentable monument to his virtuosity.

It is a very great pity that during the latter years of his life Muir's contribution to motion pictures diminished. One sometimes wonders why. Perhaps the amount of time he spent in the training of youth orchestras was partly to blame. Perhaps it was partly the fact that, either through parsimony or stupidity or both, so many producers employed the composer/ conductor - thus depriving themselves of the enormous benefits of having the skilled technician on the rostrum with the - equally skilled - composer in the control room. Whatever the reason there is no doubt that some undefinable spark left films when Muir stopped breezing into the studio screaming for action.

There cannot be many members of the Guild who never worked with Muir. Nor can there be any who would not put their hands on their hearts and vouch for his uncanny skill in getting the awkward cue to fit. It was not his fault - nor the composer's - that somebody had taken twenty feet out of a sequence the day before recording. But it was his expertise which decided which four bars had to be removed, so that everything still fitted, and everybody was still happy. I loved working with him. So did we all. But woe betide me if there was not a large gin and tonic in the cupboard upstairs at the end of a session. After all, he was a magnificent host at home - and, incidentally, a darned good cook!

I mentioned earlier his enthusiam for youth orchestras. This was an aspect of his work which is perhaps less well known to film technicians. But for the past ten or fifteen years it was the dominating influence on his life. It began when he was approached, diffidently, by the Harrow education authorities, who asked him to advise on the musical appreciation of children in that district. Within an incredibly short time the musical life of these children was revolutionised. Many times have I seen two thousand young people crowding the Granada cinema in Harrow, and Muir, with his uncanny charm and skill, taking the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra through a movement of the New World, and telling the kids what to listen for. And they screamed for more. This activity soon spread through the length and breadth of the country. He may not have done much motion picture work during his latter years, but he was far from idle. And who would question which was the more valudble occupation?

Well, it's all over now. The kids in Harrow, and Norwich, and Oxford, and all over the place, will have to get on without him. Somehow even the beautiful old mulberry trees at Shogmoor won't seem quite the same. The older one gets the more frequently do these sad things happen. I, personally, will miss Muir more than I can say. I shall not be the only one.

Sir Arthur Bliss on Muir Mathieson

As I Remember, London Faber and Faber, 1970, p. 106

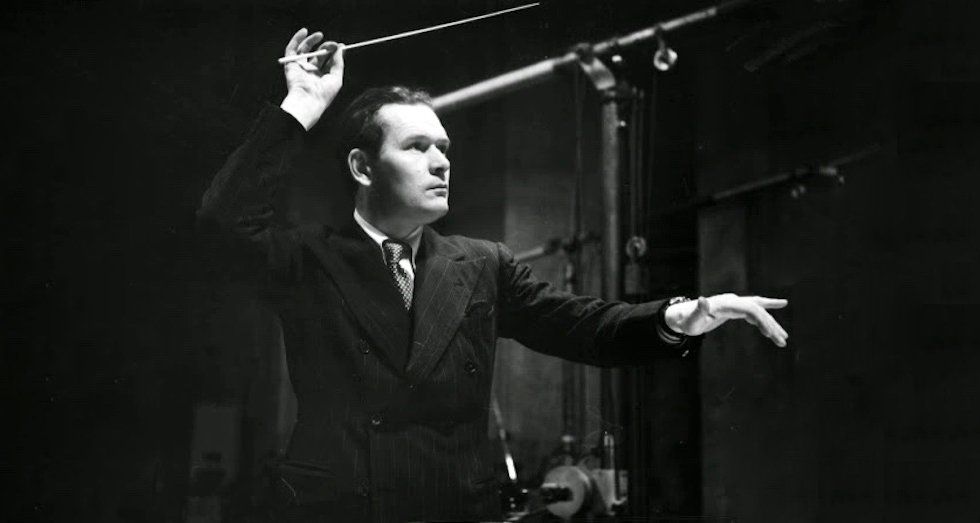

One of the enjoyments for me of going down to the sets in Denham was watching the skill of the cameramen, the recording engineers, the cutters and, especially, the musical direction. This was in the hands of a young Scotsman, Muir Mathieson, who was to gain a great reputation as a conductor for musical film scores, and in his determined way to influence directors to commission special music from our own composers, Vaughan Williams, Walton, Alwyn, Arnold and many others. It is a fatiguing and anxious job fitting music to a film, and I used greatly to admire Muir at work, baton in one hand, stop-watch in the other, one eye on the film and the other on his players. He was so type-cast for this particularly exacting work, that his great abilities as a conductor of public concerts have been overlooked, and that is the musical world’s loss.