W. Franke Harling

In the autumn of 1930, RKO-Radio studio executives tried to hire W. Franke Harling to write a back ground score for CIMARRON, their most expensive film to that time, but, as Max Steiner mentions in his autobiography (“Notes to You”) “Franke was busy at Paramount and couldn’t accept the job.” Composers were thin on the ground in Hollywood in those early-Talkie days, and so Steiner, the new Head of RKO’s Music Department (he had been engaged the previous year as an orchestrator), was asked to try his hand at composing a score. “Don’t spend too much money,” they told him, “and if we don’t like it, we’ll get somebody else to do it over. Just give us enough so we can have a preview.” Steiner scored the picture in fine fashion within the limits set by his studio, and it previewed at the Orpheum Theatre to rave press notices, some of which singled out his (uncredited) music for particular praise. His score stayed in the picture. CIMARRON, Max’s “real beginning in Hollywood”, went on to win the Best Film Academy Award, and to become the top money-spinner of 1931 in both America and Britain. It conferred major studio status upon RKO, made a star of Oscar-nominated Irene Dunne, and totally revived Richard Dix’s declining film career.

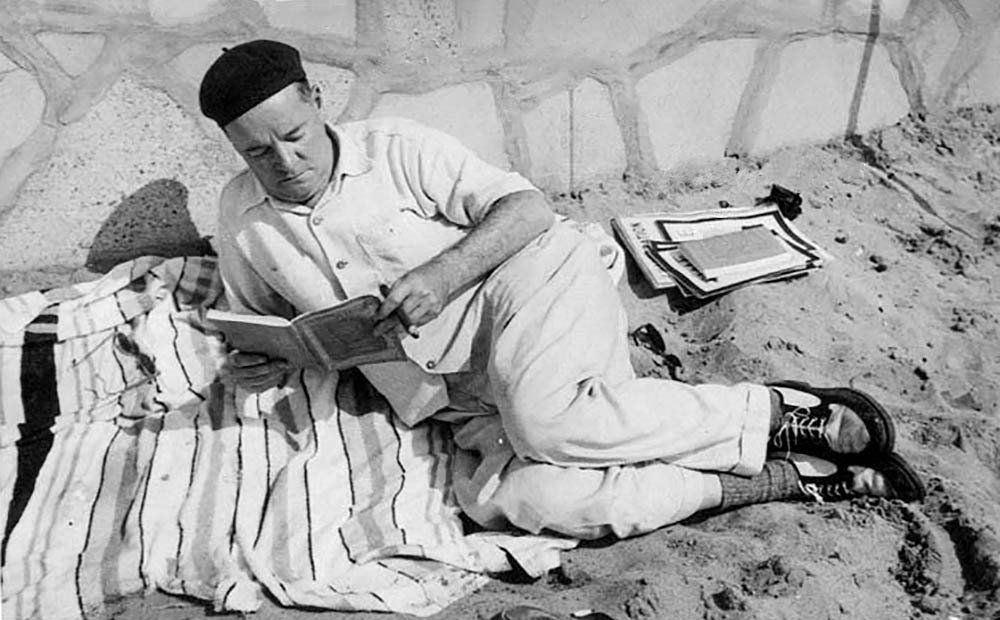

RKO’s first choice of composer, William Franke Harling, a talented, sophisticated and thorough musician, was born in London, England, on January 18, 1887 - a year and country which were to see Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee celebrated with much splendour and rejoicing. His family emigrated in 1888 to the U.S. He received his musical training at New York’s Grace Church Choir School and, returning to England, the Royal Academy of Music, London. He specialized in the organ, and when he was twenty his proficiency gained him the appointment of organist and choir director at the Church of the Resurrection, Brussels. From 1909 to 1910 he held a similar post at West Point Military Academy, New York, where he composed his famous march “West Point Forever” and his equally notable hymn “The Corps”. During his two years in the Belgian capital he had studied composition under Theophile Ysaye, the pianist-composer, younger brother of distinguished conductor-violinist Eugene. Over the next two decades Harling achieved considerable esteem in the U.S. as a composer. The continual development of his artistry is revealed in his output of more than a hundred published works: classical concert pieces (e.g., “Venetian Fantasy” and the symphonic poem “Chansons Populaires”); cantatas; church music (his sacred idiom was influenced by his early schooling and occupation); a number of popular songs; music for stage plays; a Jazz Concerto; large religious choral works, such as “Exordium and Psalms”, “A Bible (Old Testament) Trilogy”, “The Lord is My Shepherd”; etc. In May 1918 one of his biggest choral works, “The Miracle of Time” was given a gala premiere at the Tri-City Festival, Newark, New Jersey; another, “Before the Dawn”, was first performed in 1933 at the Hollywood Bowl. On December 26, 1925, the Chicago Civic Opera Company premiered his one-act opera, “A Light From St. Agnes”, in June 1929; it was staged in Paris, France. His lyric drama, “Deep River”, was successfully presented in New York in 1926.

When the depression hit the world of American music simultaneously with the advent of Talkies, W. Franke Harling signed with Paramount to contribute songs, incidental music and scores to major films in Hollywood, starting with Ernst Lubitsch’s MONTE CARLO, David O. Selznick’s HONEY and Ruth Chatterton’s THE RIGHT TO LOVE (all released in 1930). Throughout the thirties he broke a lot of new filmusic ground, working for Paramount - and for Warners, RKO, Universal, Columbia and United Artists - on pictures starring Gary Cooper, Bette Davis, William Powell, Barbara Stanwyck, George Brent, James Cagney, Marlene Dietrich, Pat O’Brien, Loretta Young, Paul Lucas, Jeanette MacDonald, Spencer Tracy, John Wayne, Margaret Sullivan, George Raft, Sylvia Sydney, Fred MacMurray, etc. He collaborated with Richard Hageman John Leipold and Leo Shuken on the 1939 Academy Awarded score for STAGECOACH. His film activities decreased in the 1940’s as he approached his 60th year, and he turned again to writing for the concert hall. In 1944 he composed his symphonic tone poem “Monte Cassino, In Memoriam”; in 1946, Three Elegiac Poems, for cello and orchestra. He died on November 22, 1958.

Harling's most productive movie year was 1932, w hen he scored: MEN ARE SUCH FOOLS for RKO; THE BITTER TEA OF GENERAL YEN for Columbia; SHANGHAI EXPRESS, THE MIRACLE MAN, THIS IS THE NIGHT (with songs by Ralph Rainger. Cary Grant’s first picture), MADAME BUTTERFLY and three more Lubitsch films - ONE HOUR WITH YOU (music Director), BROKEN LULLABY and TROUBLE IN PARADISE - for Paramount; and PLAY GIRL, THE EXPERT, FIREMAN SAVE MY CHILD, THE RICH ARE ALWAYS WITH US, ONE WAY PASSAGE (Harling’s winsome, Hawaiian styled love-song, “Where Was I?”, with lyrics by Al Dubin, was extensively used in Warner’s 1940 remake entitled 'TIL WE MEET AGAIN, to orchestral arrangements by Ray Heindorf), SO BIG, WINNER TAKE ALL, TWO SECONDS, WEEKEND MARRIAGE and STREET OF WOMEN for Warner Bros.

His score for Lubitsch’s cynical comedy-thriller TROUBLE IN PARADISE, is typical. The film tells of two charming international crooks, Gaston (Herbert Marshall) and Lily (Miriam Hopkins), who begin a flirtation in Venice and continue it in Paris, where they plan to fleece a rich widow, Madame Colet (Kay Francis); Gaston falls for the widow, but eventually renounces both her and her wealth, and departs for Madrid with Lily. Harling's scoring is polished, economical and sure-footed; every bar is relevant and his tunes are well-shaped. About 25 of the film’s 80 minutes contain music. Over the opening credits, an ardent operatic tenor sings Harling’s romantic title ballad (lyrics by Leo Robin). The melody has a tango dance rhythm and becomes Gaston and Madame Colet’s love theme, sounding sultry and sensuous early on, but fragile and poignant in their final scenes together. A gondolier is heard singing “O Solo Mio” while Gaston, disguised, robs Francois (Edward Everett Horton) at the Grand Hotel, Venice; the initial notes of the tune recur, with increased urgency, each time Francois encounters Gaston in Paris and tries to identify his suspiciously familiar face. A French radio commercial jingle advertizes Madame Colet and Company's perfume, and this sprightly piece of Parisian frou-frou accompanies Madame as she goes shopping. For the Paris theatre sequence there is a 3-minute opera excerpt. A buffo scherzo satirizes Francois and the Major (Charles Ruggles), Madame’s two pompous admirers; an elegant waltz adorns the dinner-party scene; the jealous Lily flounces out of a room to an explosive brass climax, which is repeated when she flounces back in again. Gaston and Lily’s theme, a lovely, tinkling, Venetian barcarole, is pure moonlight and champagne, floating in and out of the picture in different featherweight arrangements, mostly for mandolin and strings. The spiralling variation leading up to the finale expresses the joy of their reunion, and simulates the sound of the spinning taxi wheels as Gaston drives off with Lily. The tune is played allegro over the end credits.

Some of W. Franke Harling’s later film scores: 1933: A MAN'S CASTLE; CRADLE SONG; A KISS BEFORE THE MIRROR; BY CANDLELIGHT. 1934: THE SCARLET EMPRESS (with John Leipold: adaptation of Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky); ONE MORE RIVER. 1935: So Red the Rose. 1936: THE GOLDEN ARROW (with Heinz Roemheld); I MARRIED A DOCTOR; CHINA CLIPPER. 1937: SOULS AT SEA (with Milan Roder); MOUNTAIN JUSTICE. 1938: MEN WITH WINGS (with Gerard Carbonara). 1939: STAGECOACH (in collaboration: Oscar-winning score). 1941: PENNY SERENADE (the film in which heroine Irene Dunne introduces flashbacks with her combined scrapbook and record album, playing old records of “Missouri Waltz”, “You Were Meant for Me”, “Poor Butterfly” and “Moonlight and Roses”); ADAM HAD FOUR SONS; ADVENTURES IN WASHINGTON. 1942: THE LADY IS WILLING. 1946: THE BACHELOR'S DAUGHTERS.

Publication: The Max Steiner Journal / Issue No.1 / 1977

Publisher: Max Steiner Music Society

Copyright © 1979, by Max Steiner Music Society. All rights reserved.