DIE SISTER, DIE! (1972; aka THE COMPANION) had to do with a man who hires a nurse to care for his shrewish and suicidal sister Amanda (Edith Atwater), while secretly coercing that caretaker to put his elder sibling out of her misery. The 75-year-old composer had a limited budget to work with, which would accommodate no more than a chamber orchestra. “That [kind of film] means less notes, but more thinking about the notes that I put on paper,” Friedhofer wrote to a friend about this assignment, later describing the music he was writing as “neurotic as all get-out, post-serial and polytonal without a pure consonance in a carload” (quoted by Linda Danly in Chapter 2 of Hugo Friedhofer: The Best Years of His Life). The score begins private-parts-postermelodically and innocently, setting down a gentle and fluid tone as Edward (Jack Ging) hires Esther (Antoinette Bower), a former nurse with a sordid past to care for his sickly sister. When he informs Esther of Amanda’s prior suicide attempts and suggests if she intends to attempt a third time, “she must not fail,” the music turns significantly somber, underlining the dead seriousness of Edward’s suggestion. It will proceed with soft menace as the story continues with this facet in mind. A series of light, Herrmannesque chord progressions will roam across the soundscape as the story develops and Esther performs her job; but the music also paints an elaborate portrait of Amanda and her own past, far clearer than the ominous reflections of self-serving Edward. Most of the music plays under dialogue, subtly underlining the growing tensions and misgivings growing within Esther as she grows to respect the old woman. Friedhofer’s angular impressions for the flashback that reveals Edward and Amanda’s true past connection leads into a series of tremolo string figures doubled by low woodwind blares, intoning after Amanda mistakes Esther for her dead sister and collapses. An effective, driving suspense theme propels them as Edward and Esther look for the missing Amanda, with rhythmic vibrato strings offset against flailing woodwind piping, evoking tension; later pizzicato strings build powerful suspense at the film’s climax, as Amanda seeks refuge in a church, and then must hide from Edward when he appears in the same house of worship

Friedhofer & Fantasy

Randall D. Larson - Film music columnist for buysoundtrax.com and author of nearly 300 soundtrack album notes and several books on film music, including a newly-released second edition of Musique Fantastique: 100 Years of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Film Music, from which this article has been extracted and modified.

One of the finest orchestrators of Hollywood’s Golden Age was Hugo Friedhofer, who worked on hundreds of films since 1930 as orchestrator, composer, or co-composer, mostly without screen credit. He got his start in Hollywood in 1929, becoming a session player for Fox Studios, and later moved to Warner Bros as an orchestrator, deftly expanding treatments by Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold into full orchestral scores. In 1946, Friedhofer extricated himself from the studio system and began to freelance; his score for RKO’s THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES (1946), about the homecoming of a trio of WW2 vets, won him an Oscar for best music; among eight other Oscar nominations he received during his career.

Like many film composers, albeit perhaps less frequently than some, Friedhofer occasionally scored films within the fantasy, science fiction, and horror genres, and has brought his own voice of musical expression to these evocative films. Avoiding movie monsters and attacking aliens when scoring a film by himself, Friedhofer’s explorations into the fantastic cinema revolved mostly around psychological horror, where he used music to identify and reflect the central mystery of the suspicious character(s) and also to enhance the resultant apprehension and suspense those characters’ interactions create in the storyline. His first score in the horror/thriller genre was for THE LODGER (1944), John Brahm’s remake of the silent Hitchcock classic, in which Laird Cregar is a hotel guest who turns out to be Jack the Ripper. Friedhofer had just completed writing Main Title music for Hitchcock’s sea-bound thriller LIFEBOAT (which is all the music that is in the film) when this grim mystery in the London fog came his way. The music is appropriately atmospheric and grim, supplying a darkly impressionistic picture of the London in which the story takes place. Noted for its orchestrations, Friedhofer’s writing for low winds and brass is exemplary, giving the film music of his brooding flavoring, while also adopting the characteristic use of lush strings in the manner of his former mentor at Warner Bros., Max Steiner.

Friedhofer incorporated the motif of the Big Ben chimes into his music during the opening murder scene, which both sets the stage and provides a moody pizzicato for the unfortunate woman who will meet her date with destiny in the fog-shrouded Whitechapel alley. As her screams expire, a growling pattern from French horns resonates gutturally, a flurry of violins rush by (along with a dark cloaked figure) and disappear out of site. A three-note ascension of horns provides a thrill of horror as the camera turns into the corner of the alley and we see the victim’s broken wine bottle and fancy hat, as shrill police whistles vanquish the music.

The music accentuates the mystery of the mysterious “Mr. Slade,” lodging at 18 Slade Walk – is he or is he not The Ripper? When the maid delivers a meal to Slade while he is napping in his room, the music intones darkly as she enters, as if arriving into the lair of a slumbering beast; but as he wakens and they have a conversation, he shows her a self-portrait of his dead brother, his love and passion for his sibling clearly evident; the music underlies his yearning and grief, and yet even in its poignancy there is an underlying tone of menace, as if perhaps this, too, is not all it seems; or, as we shall see, the memory of his brother’s demise fueling his homicidal misogyny. Friedhofer underlines the sadness and human-ness of Slade as much as he accentuates the terror of the Ripper’s action and violence. There’s a marvelous mysterioso when Kitty Langley (Merle Oberon) wakes up one night to smell smoke; investigating she finds Slade in the basement burning a stained coat in the fire. Brahm’s moody direction of this sequence, with its superlative balance of shadow and brightness, aided by Friedhofer’s intricate pattern of flute, harp, and string harmonies, builds a striking tension. Slade’s late excursions into the night fog are escorted by a compelling array of dark, undulating low winds.

The climax, where Slade is chased through the scaffolding of a theater, is a marvel of dynamic accompaniment. Vivid gashes of strings pierce through layers of hulking brass, rising and falling, with shouts of winds escalating as Slade, wounded, climbs higher up the curtain apparatus; brooding low winds over tremolo violins and cautionary warnings of trumpets as he makes one final attempt on Kitty’s life, the full orchestra raging cyclically and rising higher, holding with horn figures dangling like the heavy sandbags Slade is aiming to drop on the resting Kitty below, repeating chords emphasizing our tension, until Slade is spotted and the chase renewed, the massive orchestral onslaught dissolving down to a single trumpet as Slade is cornered in the theater, and then stinging violin notes, their yearning melody piercing, speaking for the panic, desperation, enmity, and tortured soul of Mr. Slade as his wild eyes stab knifelike into those of his imminent captors, and then a final low ringing horn, doubled by a soft timpani roll, and then utter silence, only Slade’s rough, panting exhalations sounding through the silence as police and villain stare each other down, panting louder, louder, eyes and knife glinting alike in the incandescence of the confluent hallways, and a sharp flutter of descending violin melody capped by a resolute horn chord as Slade turns and bursts through the window behind him, splashing into the rough river below… It’s a brilliantly executed sequence, stunningly scored and perfectly married to image, composition, choreography, and silence.

Nearly two decades later, Friedhofer encountered another psychological terror tale, this one a lot more visceral than the moody theatricality of THE LODGER. William Castle’s HOMICIDAL (1961) was a sturdy Psycho-like tale of homicide and psychosis to which the composer provided a customarily melodic, romantic, and flavorful composition – until the murder occurs like a thunderbolt ruining a beautiful day. The crime is bathed in a dissonance of blaring brasses over raucous drums and sizzling cymbals, followed by a downward rappel of low strings as the murderess Emily (Joan Marshall, as “Jean Arless”) makes her getaway and returns home. As the film moves into the deceptively pleasant domestic lives of siblings Warren and Miriam and their disturbing past, with which Emily is somehow very involved, Friedhofer provides a gentle sonority that drifts around the seemingly innocuous activities, informing the proceedings with an air of uneasiness that belies the familial decorum, since we know Emily is more than she seems. The music during the film’s climax builds a continuous, growing, potent sense of suspense through circulations of horns, winds, and strings, joined by thunderous timpani as Miriam is nearly stabbed by Emily; and then the music is gone and it’s just the two of them facing off against their own silent pounding heartbeats, as Castle works out his final reveal, with an unspoken nod to Bloch and Hitchcock.

In an interview with Irene Kahn Atkins published in Linda Danly’s splendid collection of Friedhoferania (Hugo Friedhofer: The Best Years of His Life, Scarecrow Press, 1999), Friedhofer briefly described his experiences on HOMICIDAL: “I went over to Columbia one afternoon and ran the film and was kind of fascinated with it, because, outside of THE LODGER, which goes all the way back to 1944, it was the first so-called horror film that I had ever done. Bill [Castle] was very pleased with the score. He came to most of the recording sessions. And that, incidentally, was my first and only experience in conducting an entire feature film. It worked out all right. I sort of handpicked the orchestra… it was a strange mixture of jazzmen and legitimate musicians.”

Shortly after scoring HOMICIDAL, Friedhofer scored his first (and only) verifiable monster movie: a version of BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (1962) in which Mark Damon plays Eduardo, The Beast, as a werewolf cursed to nightly transform into a wolf-man (although without the eating-flesh tendencies). Joyce Taylor is his betrothed Beauty Althea who helps find a way to end the curse. Friedhofer didn’t receive any screen credit, only Emil Newman was acknowledged in the Main Titles as “Music Director.” Friedhofer’s score is thoroughly splendid, frequently rising up from its incidental, behind-dialogue timbres and melodramatic posturing to reach some very engaging moments of musical drama. His primary theme, introduced with pageantry and old-school dignity over the Main Titles, is a lilting, classical romance seething with all the passion and heartbreak the original fable represents. While the film’s rather bland narrator describes how the curse of the sorcerer Scarlatti beset Eduardo, the ruling duke and heir to the throne of a Middle Ages kingdom, Friedhofer engages in some innocuous melodrama, which suddenly sprouts forth with jagged trumpets and unyielding timpani as we see the beast the duke becomes (courtesy of make-up by Jack [THE WOLF MAN] Pierce). Even here the resonance emits a heraldic tone of majesty, and as the effects of the full moon have their way, Friedhofer’s music turns soft, pityingly, reflecting the truth that Eduardo’s werewolf is not some slavering monster but a dignified man trapped in a werewolf’s body, unable to properly rule his kingdom or wed his beloved.

Midway through the film, during the climactic scene in which Althea discovers Eduardo’s hidden secret, Friedhofer builds anticipation with each of her footsteps, as she follows Eduardo downstairs into the castle’s catacombs. Each descending trounce is echoed with a rising chord in the music, each inch closer to the activities behind the closed door are punctuated by a pounce forward in the orchestra, anticipating the imminent reveal as if it were the Phantom’s own unmasking; when Althea finally bursts into the room and faces the furry fanged face of her fiancé, the music explodes with blasting measure from the trumpets, shrieking over swaying strings – electrifying the woman’s shock, horror, grief; then dissipating into ether as she screams and sinks to the ground in a caricatured faint.

Friedhofer’s music for BEAUTY AND THE BEAST demonstrates some exemplary brass writing, stressing accentuating danger, tenuously underlying suspense, cultivating horror. The music sometimes adopts the structure of conventional melodrama, such as when Althea stares at the locked doorknob of her room in Eduardo’s castle, seeing it slowly turn, in one direction, and then back again, clicking in distressful intensity… Or when Eduardo and his advisor Orsini search the catacombs for the hidden tomb of Scarlatti, hoping to find a means of ending the curse. Once found, Eduardo engages two workmen to dig their way into the crypt, only to find out the men are enemies trying to steal his kingdom, and a dramatic fight between them ensues; rather that re-use his brass action music, Friedhofer articulately scores the sepulcher fight with rapidly discordant piano, a wholly new musical timbre for the score. As the enemies are vanquished and the lycanthropy curse ebbs away from Eduardo upon hearing a declaration of love from Althea, Friedhofer’s cyclonic string music swirls away in reverse, and the score resolves stridently and powerfully, as Beast is made wholly man again through the love of Beauty.

By the mid-1960s, Friedhofer, like many of his contemporaries who had defined and developed the structure, style, and scope of film music since the 1930s, found themselves relegated to working in television – the end of the Hollywood studio system having eradicated steady opportunities for them in feature film scoring. Friedhofer scored some handfuls of episodes for VOYAGE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA, I SPY, THE GUNS OF WILL SONNETT, and LANCER. He did a Roger Corman war movie in 1964 called THE SECRET INVASION, a made-for-TV comedy-Western called THE OVER-THE-HILL GANG, and a final Corman war movie in 1971, VON RICHTHOFEN AND BROWN. Ironically, Friedhofer’s final two feature film scores would both be for low-budget horror thrillers, concluding his career with a return to a genre in which he was rarely engaged.

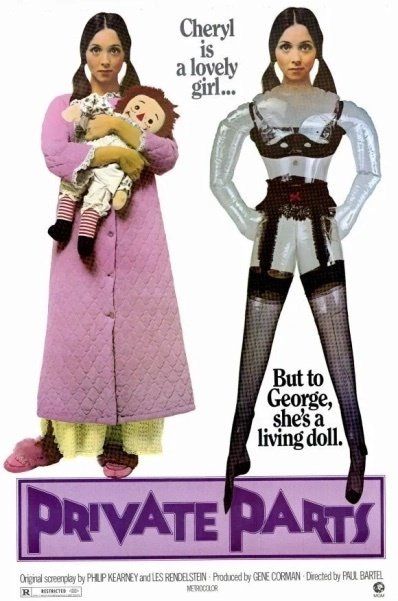

Friedhofer’s last feature film score was for PRIVATE PARTS (1972; aka BLOOD RELATIONS), Paul Bartel’s ribald horror comedy about Cheryl (Ayn Ruymen), a young runaway who checks into her spinster aunt’s skid row hotel, unaware of auntie’s murderous predilection. With the rise of electronic instruments finding a home in science fiction movies of the early 1970s (THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, RUSSIA’S SOLARIS) as well as in low-budget horror movies from neo gore auteurs Ted V. Mikels and Bob Clarke, Friedhofer maintained a traditional orchestral approach to PRIVATE PARTS, achieving some of the same kind of audible shrieking that Mellé, Carlos, and Zittrer were accomplishing electronically through his own acoustic orchestral means. Friedhofer’s unsettling music is both elegant and dramatic from the very start, as brooding violin misteriosos are offset against braying horns and sultry saxophone inflections to evoke a disorienting anxiety right from the main titles.

Friedhofer’s last feature film score was for PRIVATE PARTS (1972; aka BLOOD RELATIONS), Paul Bartel’s ribald horror comedy about Cheryl (Ayn Ruymen), a young runaway who checks into her spinster aunt’s skid row hotel, unaware of auntie’s murderous predilection. With the rise of electronic instruments finding a home in science fiction movies of the early 1970s (THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, RUSSIA’S SOLARIS) as well as in low-budget horror movies from neo gore auteurs Ted V. Mikels and Bob Clarke, Friedhofer maintained a traditional orchestral approach to PRIVATE PARTS, achieving some of the same kind of audible shrieking that Mellé, Carlos, and Zittrer were accomplishing electronically through his own acoustic orchestral means. Friedhofer’s unsettling music is both elegant and dramatic from the very start, as brooding violin misteriosos are offset against braying horns and sultry saxophone inflections to evoke a disorienting anxiety right from the main titles.

In his notes to the Hugo Friedhofer Film Music score recording (Facet CD, 1987), Tony Thomas quoted Friedhofer speaking about his PRIVATE PARTS score: “The score is, for the most part, serially organized – and I can account for every permutation of the one basic tone row, which, so to speak, is the spinal column of the whole, and its unifying factor… in which I strived for the aural equivalent of the smell of musty carpeting, termite-infested woodwork and Lysol disinfectant, the fetid characteristics of beat-up hotel on the edge of Los Angeles’ skid row.” Friedhofer holds true to a blistering chromatic approach in his use of different parts of the orchestra that, regardless of being restricted to the ordered pitch of a given tone row, construct a thick musical pattern through skilled symphonic orchestration.

PRIVATE PARTS is also Friedhofer’s most modern score, both in its advanced serialism, but also as aspects of modern jazz creep into the score to give Cheryl her young, hip attitude, which contrasts tellingly against Aunt Martha (Lucille Benson). “Friedhofer’s score for PRIVATE PARTS is more atonal than most scores written in Hollywood [at that time] and it has an edgy intensity that hovers over the picture rather than lies underneath it,” wrote Tony Thomas. “The score also contains some of the best rock-jazz so far heard in a work by a serious film composer.”

The score is full of classic Friedhofer moments, from pensive clarinet and flute filigrees to furtive figures of winds and strings keeping the audience continually off-balance and ill-at-ease. The earlier jazz inflections are reprised for rhythmic piano and cello over reverbed percussion as Judy comes to find Cheryl and discovers disturbing photos in the basement dark room. The music makes the creepy scene creepier, until the lights go out and Judy creeps no more. Piercing, ultra-high string and electronic pitches suggest the dual psychological aberrations when Cheryl, knowing voyeur George is watching through the wall, bathes seductively for his benefit. Friedhofer interpolates the hymn “Rock of Ages” in a few places, suggesting the religious fanaticism of Aunt Martha, particularly at the end when Cheryl assumes her aunt’s role as proprietor of the hotel. Elsewhere, Friedhofer alludes to another hymn, “There is a Happy Land, Far, Far Away,” in reference to the inherent madness that runs rampant in the hotel.

Over his forty-plus years a Hollywood music man, Hugo Friedhofer contributions to films big and small were among the most notable, from the Golden Age to the low-budget imaginations of independents three decades later. In the fantasy-thriller genre, as we have seen, his efforts were few but very effective. Recordings are available of the first and last of these scores: William Stromberg conducted the Moscow Symphony in a vibrant and evocative rendering of THE LODGER, reconstructed and orchestrated by John Morgan, released in 1997 on Marco Polo’s aptly named THE ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO CD along with selections from the titular film score as well as THE RAINS OF RANCHIPUR and SEVEN CITIES OF GOLD. The same Lodger tracks appear on Marco Polo/Naxos’ Murder and Mayhem CD, released in 1999 along with suites from Victor Young’s THE UNINVITED and Max Steiner’s THE BEAST WITH FIVE FINGERS. Tony Thomas produced a private label recording of extended suites from PRIVATE PARTS along with RICHTHOFEN AND BROWN, performed by the Graunke Symphony of Munich, issued on a CD called The Film Music of Hugo Friedhofer (spine and CD labels read Hugo Friedhofer Film Music) from Facet Records (distributed by Delos) in 1987. Here’s hoping a grand presentation of Friedhofer’s BEAUTY AND THE BEAST and his psychotic discordance from DIE SISTER DIE may be presented on disc or digital download in the near future.