An Interview with Elmer Bernstein

Originally published in Films and Filming March 1978, pp 20-24

Copyright © 1978, by Hansom Books. All rights reserved.

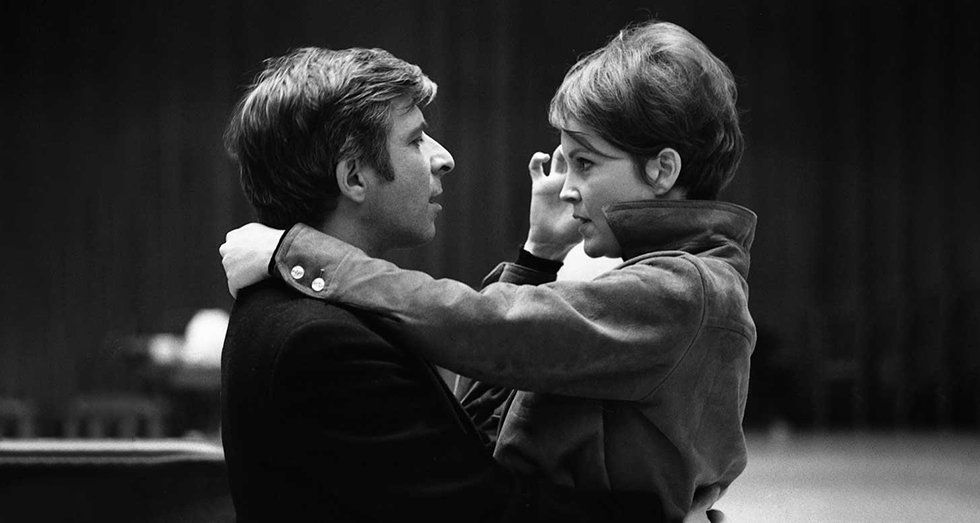

Photo: Elmer Bernstein working with actress Marlyn Mason on the 1967 Broadway play How Now Dow Jones

In many respects Elmer Bernstein represents the other side of the film composing coin to my first interviewee in this series, Miklos Rozsa. Bernstein’s career in this department took shape during the Fifties - the period which saw the decline of the big studio ethic and the neo-romantic approach to scoring, and the rise of television - and consolidated itself during the Sixties, effortlessly encompassing the demands of TV and such potential bêtes noires as theme songs, etc. Bernstein has been equally prodigious in other fields: ballet and dance music, incidental stage music, a musical (HOW NOW DOW JONES, 1967), documentaries, and over 20 TV series and documentaries. At the time of the interview he had just finished scoring the series THE CAPTAIN AND THE KINGS and considered it amongst his very best work, stressing the fact that, in America at least, TV was now a vitally important source of income and experience for any film composer.

The fact that he has musically survived what many consider an assault-course for a composer’s integrity is a tribute to his craftsmanship. And he is quick to point out that composers who are castigated nowadays for having sold out by writing bland, pop-oriented scores (when they have proved earlier in their careers that they are capable of better things) should not entirely be held to blame; the villains are more the producers who demand such product and who, with no more qualification than that of holding the purse strings, do so much to change the market.

Elmer Bernstein (pronounced ‘Bernsteen’, incidentally) was born in New York City on April 4, 1922. Musically gifted, he first pursued a career as a concert pianist, coming to film music via experience in the army with radio scoring. He is most identified - at least on this side of the Atlantic - with things and sensibilities American, yet this talent has manifested itself in a wide variety of genres and, chiefly during the Fifties and Sixties, with consistently innovatory flair (even some years before the renowned THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, for instance, he was already avoiding traditional western music cliches in DRANGO). A brief glimpse at only some of Bernstein's major scores shows his great diversity: the spectacular/’epic’ (THE TEN COMMANDMENTS, THE BUCCANEER, THE MIRACLE, HAWAII, KINGS OF THE SUN), tough, jazz-inflected (melo)-drama (THE SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS, THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM, THE CARPET BAGGERS, WALK ON THE WILD SIDE), showbiz tinsel (THOROUGHLY MODERN MILLIE, THE INCREDIBLE SARAH), comedy/thriller fare (THE SILENCERS, I LOVE YOU, ALICE B TOKLAS, THE MIDAS RUN), ethnic (CAST A GIANT SHADOW), gentler Americana (TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD), and westerns (THE HALLELUJAH TRAIL, TRUE GRIT, etc, etc).

Recently Bernstein has earned the gratitude of film music enthusiasts everywhere by launching his own record club, devoted to new recordings of classic scores (all done in London) which have generally used the films’ original cues rather than the dreaded spectre of the re-hashed suite. Backed by musical and intelligent sleeve-notes and a magazine (Film Music Notebook) stuffed with interviews and information, the series is already of landmark status. Steiner's HELEN OF TROY and A SUMMER PLACE [FMC-1], Bernstein's THE MIRACLE [FMC-2] and TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD [FMC-7], Waxman’s THE SILVER CHALICE [FMC-3], Newman's WUTHERING HEIGHTS [FMC-6], Rozsa's YOUNG BESS [FMC-5] and THE THIEF OF BAGDAD [FMC-8], Herrmann's THE GHOST AND MRS. MUIR [FMC-4] and (the rejected) TORN CURTAIN [FMC-10], and North's VIVA ZAPATA! and DEATH OF A SALESMAN [FMC-9] have been issued so far; Rozsa's MADAME BOVARY [FMC-12] is scheduled next.

The following interview, for which Bernstein kindly found time amid a fraught schedule, took place last January [1977*] when he was here recording THE THIEF OF BAGHDAD, it was conducted under less than perfect circumstances but still, hopefully, gives some idea of the man and his methods. Bernstein is not naturally given to anecdotes when being interviewed but is otherwise both helpful and attentive in conversation. A conductor of considerable experience and talent, he remains affable and good-natured even under the most trying circumstances in a studio, and obtains results from players quickly and efficiently; outside the studio and away from a tape recorder he is a relaxed and witty conversationalist, when time permits. For his Film Music Collection, already as much as for his own compositions, he deserves enthusiasts' greatest respect - not simply for the considerable courage required but also for its implicit avowal of faith in the durability and worth of film music in its original, rather than re-arranged, state.

First of all, how exactly did Film Music Collection come about?

The genesis is rather interesting, as a matter of fact - totally accidental. Some years ago I wrote an article for a magazine about the state of film music. I was very critical about a lot of things which have improved since then! In the course of the article, quite casually, I mentioned scores had never been recorded, that they would disappear and be forgotten; wouldn’t it be nice, I wrote, if they could be preserved. Well, I got an absolute avalanche of mail: people said, ‘Go ahead and do it’, and some even sent small amounts of money! I was so impressed by that that I went to some business people and suggested the formation of a small company with that specific purpose. At that point, though, there was absolutely no enthusiasm for the idea. Some months later, Charles Gerhardt and George Korngold went and did THE SEA HAWK album for RCA, which was a tremendous success, so I went back to my business people. But they were still reasonably disinterested, so I decided to form the Film Music Collection on my own, strictly as a wholly-owned enterprise. That, quite simply, is the history of it. At the time I suspected that, worldwide, there must be some 10-15,000 people who would buy almost any respectably-done good score. But the response, in terms of membership, came somewhat slower than I had anticipated, thereby causing a tremendous economic problem. We have a membership now of something less than it would take to make the enterprise self-sustaining; it’s growing all the time, of course, but not nearly fast enough. And I've been loath to accept a tie-up with any large commercial record company which would compromise the purity, the ‘non-commercial’ status, of the series. By ‘non-commercial’ I mean that we like to present the scores in their reasonably original state rather than making so-called ‘Themes from…’ and changing the character of the material itself. But it may come to a point where we have to accept a tie-in with a major to ensure survival because up till now I’ve been subsidising it myself. (A temporary deal with Warner Bros Records has since helped to ease the situation).

Musically speaking, what was your early background?

Well, I was originally trained to be a concert pianist, and did in fact perform as that until 1950. In 1950 I was afforded an opportunity, as a result of some radio work I had done, to do the music for a film in Hollywood called SATURDAY’S HERO, and ever since then I’ve been writing music commercially.

But from your earliest roots … were your parents musical?

Oh, yes. Yes, indeed. My parents were not themselves musicians but they were very interested in culture in general and I was given a background not only in music but also (in fact, even more, as a child) in painting. I also did some acting and for a short period was a dancer. I was close to all these things quite consciously through my parents, but I gravitated to music by myself. When I was about nine or ten my parents came to live over here, in France and England. It was in France that I began to become more and more interested in music and I took piano lessons there. When I got back to the United States in 1934 I was ill for a while, but by the time I was fourteen or fifteen I remember I was pretty clear in my mind that I wanted to be a musician - a concert pianist, primarily, but I was also interested in composition. Like most children I wasn’t wildly interested in doing scales the whole time on the piano and I used to do a lot of improvising. Fortunately, my teacher [Henriette Michelson at the Juilliard School in New York], instead of discouraging me, decided to try and find out if it was an omen of talent and took me to a young colleague of hers who at that time was 33-years-old (it seems hard now to imagine all this - it was Aaron Copland). I remember I played him a little A minor waltz on the piano, and he sort of started me off on my career. He wasn’t teaching himself at that time - he’d just returned from studies in Paris with Nadia Boulanger - but he sent me off to someone else. I owe my teacher a lot in that regard: she didn’t discourage my interest in composition, even though at that point in my life I fancied the emphasis would be on piano-playing. And it continued like that until my late twenties.

When came the switch away from a straight career as a concert pianist?

Well, I suppose to some degree I owe my career in composition to World War Two … When I was in the army I ran into a friend who knew me from civilian life - he was in the sort of propaganda section of what was then called the United States Army Air Force - and I was organised to do some arrangements of American folk songs for their radio shows. That was a field of interest of mine: it seems odd now, but in those days American folk music was a virtually unknown area. I started to do orchestral arrangements of these songs, and one day a gentleman who was a composer of dramatic music for the shows got angry because a script was late and made himself unavailable. As a result of this I was asked by the music director whether it was possible for me to write a score for the show, and, being young at the time, I assured him very much that it was! So I got my apprenticeship through doing music for those shows. I had, of course, always studied composition alongside piano, from the time of working with Copland’s protégé, Israel Sitkiewitz, and thereafter with Roger Sessions and Stefan Wolpe, but it had been mostly theoretical. It had been just part of my education. At the end of the War I was still studying composition but I went back to a concert career from 1946 to 1950. I gave my last solo piano recital in New York Town Hall in March 1950.

Did you have any thoughts on a career composing concert works?

Well, it’s a question I’m asked quite frequently: do I have ambitions, let’s say, to write major symphonic works? I suppose in an abstract sense, yes. I’d probably enjoy writing a major choral work, which is something that has always fascinated me, but the negative side is that I find it very difficult (at least for my temperament) to spend a great deal of time composing a work and then having to convince people to play it. Even with a commission, somebody’s going to play it once and then that's the end of it. I find that very discouraging.

And presumably being known as a ‘film composer' would work against you in the concert world?

I think it probably would. Another problem, although it's not an insurmountable one, is that one develops rather different techniques for writing film music. If I had to write a sustained work I would probably want to study an exercise for about six months beforehand - to prepare myself for work in a larger form. I've already done several suites for orchestra, several song-cycles, which are totally non-film-related. They're very different stylistically: the musical language is more obscure. You have to remember when you're writing film music that you are attempting to communicate with a vast audience, and it must indeed be communication. If the language of the music is so obscure that it can only be understood by a few, then I don’t think it's very useful as film music. If you’re writing concert-hall music, you’re basically writing for a very much smaller audience and can indulge yourself in a much more personal kind of expression. I definitely consider myself a linear composer, rather than a composer of orchestral effects; my approach to music is more concrete, rather than impressionistic. Harmonically my film music is highly tonal; my concert works not nearly so much. If I did do a great deal of concert composing, I would probably become a sort of split musical personality; I think I'd find it difficult, or impossible. Someone like Rozsa has a totally unified style - his personality is clearly recognisable in both his concert and film works. He has no split personality.

Do you have perfect pitch?

I do not. But I have a very highly developed sense of pitch.

Do you compose at the piano or away from it?

I can, and do, do both. Ideally, I prefer to compose away from the piano but I have to be somewhat more relaxed to do that. I have to have more time. Having been a concert pianist, I’m always highly suspicious of sitting at the piano and letting my fingers do the thinking. I don’t think fingers are very intelligent.

Do you think in terms of colour from the very beginning?

This depends on the circumstance. I don't think you can really separate a piece of material from its colour, though. I’m not that linear. In Baroque music - Bach, for instance - the lines are so persuasive that what instrument plays them is not nearly so important; the lines are going to survive no matter what instrument plays them. In our age, though, one cannot separate the two.

To what extent do you orchestrate your own music?

In most instances where there’s any time at all, I virtually orchestrate the picture myself, in the sense that the sketches are so detailed that ideally the orchestration becomes a sort of high-class copying job. It also depends very largely on the nature of the picture itself. For instance, TO KILL A MOCKING BIRD was very dependent upon specific colours, and I basically orchestrated the thing myself. Whereas with THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, which was basic ally symphonic in character, I tended to be less detailed in my sketches.

Have you worked regularly with the same orchestrators?

Yes, I have. In the United States, from about 1955 until his tragic death last year, I worked almost exclusively with Leo Shuken - and his associate Jack Hayes. That association started with THE TEN COMMANDMENTS. Others … two brilliant jobs of orchestration were done by Fred Steiner for THE VIEW FROM POMPEY'S HEAD and THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM, he also helped out on THE GREAT ESCAPE. Edward Powell, another brilliant orchestrator who did most of Alfred Newman’s works, did FROM THE TERRACE, A GIRL NAMED TAMIKO and THE COMANCHEROS. In recent times I've had some younger people working for me: in the United States, my own son, Peter Bernstein, and a budding young composer by the name of Dana Kaproff; and in Britain, Christopher Palmer, who orchestrated THE INCREDIBLE SARAH. In cases where I've worked with, say, Leo Shuken and Jack Hayes - who must have done about sixty or so of my pictures, maybe even more - we got to know each other so well that we only had to give each other the punch-lines, so to speak!

Do you find any difference in the composing schedules you were being given in the Fifties to nowadays?

Oh, yes; there’s a vast difference. In the Fifties and until the mid-Sixties, contracts were on a ten-week basis; today, madness reigns - schedules are ridiculous. We're called upon sometimes to complete scores in three weeks. It's diabolical. For myself, having done over a hundred films, I’ve developed a technique which is at my command, but I can't help but feel that extra time, in which to reject or try other ideas, must inevitably result in better product.

Have you ever been forced simply to give up halfway through an impossible schedule?

I've never given up - that’s not in my nature! I'm rather dogged about it. There have been films on which I've had to have help - and it was credited as such on the screen. Two pictures jump to mind here: THE GREAT ESCAPE and THE HALLELUJAH TRAIL.

Have you ever had any scores rejected?

No, I've been very, very fortunate. So far I have escaped that phenomenon of having a score replaced. As a matter of fact, I'm not sure that I feel very good about that, because the people who have had scores replaced are much better company!

Do you normally conduct your own music at the recording sessions?

Yes. In my entire career there’ve only been three of my scores that were conducted by other people. My first two films SATURDAY’S HERO and BOOTS MALONE - were conducted by Morris Stoloff, who at that time was head of the Music Department at Columbia Pictures; and the first score I did for 20th Century-Fox, THE VIEW FROM POMPEY'S HEAD, was conducted by Lionel Newman. I'm happy to conduct my music; it’s not that my ego runs particularly in that direction, it's just easier for the studio and everyone. The same with the albums.

During your early film commissions, did you have much difficulty picking up the compositional techniques of the trade?

Don’t forget I’d had quite a wide apprenticeship, as I said before, doing dramatic music in the army, so it wasn't a totally unfamiliar field. It would be very difficult for me to assess those films; I haven’t seen them for a long time and I don’t know to what degree I succeeded or not. You know, you’re talking of some 27 years ago! The first film where I really found my feet, so to speak, was SUDDEN FEAR; that was 1952. Although I haven’t seen it for a long time, I think I’d tend to stand by that one.

Somebody said to me recently, ‘Don't ask him about CAT WOMEN OF THE MOON ’...

Ha! Well, there’s a very funny thing about that film, you know. Strangely enough, I’m rather proud of that. There were two films that I did back-to-back at a particularly low period of my career - ROBOT MONSTER and CAT WOMEN OF THE MOON. ROBOT MONSTER, I think, was a particularly interesting score; I did it with 11 instruments. It was one of the first adventures with electronic instruments in films of the time [1953]; the two main instruments were an electronic organ and a rather interesting, but now obsolete, instrument called the novachord. I relied very, very heavily on those.

On another level, you’ve also had a fair amount of mileage out of the music for THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN...

I should say! THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN was a sort of cause with me; it was one of the few pictures for which I put myself out in order to get it. As I said earlier, I had always been a student of Americana, and I had all these ideas (about the use of idiomatic music) looking for a place to go. In two pictures done very, very close together - THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN and THE COMANCHEROS - I really said most everything I had to say on that subject. What I call ‘border music’ - Mexican border music, which I have a great affection for. When the Mirisch company decided to do RETURN OF THE SEVEN, they wanted to use the original music, and they proposed to use the actual original tracks and do an editing job on them. This was put to me and I said that, rather than them do that, I'd prefer to supervise the whole thing myself; use the original material but re-record it all (here in England, by the way). There was one extra theme that I introduced which was not in the original but the main bulk of it was the same.

And then after the second sequel. GUNS OF THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, there was a final rip-off, THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN RIDE!

I'd almost forgotten that! Oh, that was done very cheaply. We took the original tracks and re-recorded them. That was an edit job; I didn’t even supervise that.

You were saying that in the Fifties contracts were generally more favourable, but on THE TEN COMMANDMENTS you were virtually on a week-to-week contract ...

Well, that’s an interesting story. When I first got involved with THE TEN COMMANDMENTS I was not the composer on record. The composer was to have been Victor Young, and I was on contract to write little dances and songs that were needed during shooting. Victor Young was at that time in New York City doing SEVENTH HEAVEN, a musical he had written for the stage. When Victor returned to Hollywood shortly before the film was ready to be scored, he was by that time not well and he felt that he couldn’t see the project through. That’s how I inherited the score; it was a great turning-point in my life, of course.

While you were writing music during shooting, were you also working on other films?

Well, I must confess that I wasn’t very much in demand at that point! The beginning of my career was very odd. I came out to Hollywood under very good auspices, and I did some A-films, but it wasn't until about five years later that anybody took any great notice of me. I did a film in 1952 called SUDDEN FEAR which attracted some attention - but for a very odd reason. I tended to write in a very transparent manner, and we were just coming out of the neo-Tchaikovsky period characterised by writers like Max Steiner; SUDDEN FEAR used fairly exotic instruments for the time - bass flutes in solos, the piano in a very exposed way, etc - and that attracted some attention. At the time of THE TEN COMMANDMENTS my position was very much that of a ‘musical secretary’, and there was nothing else to do. Except one funny thing ... There was a hiatus between the end of shooting and the time the film was ready to be scored, and by a stroke of luck, for reasons best known to himself, Otto Preminger selected me to do the music for THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM - and I did that during the hiatus.

Did you ever have any musical discussions with DeMille?

Not in the sense that you ask. DeMille very much knew what he wanted and I think the score to THE TEN COMMANDMENTS reflects DeMille much more so than it does me. I've always considered the score as one of a kind in my career. I wrote one other quite like it - almost a memorial to DeMille— and that was THE MIRACLE. It was just after he had died. But I've never written anything exactly like THE TEN COMMANDMENTS since. I mean, stylistically. DeMille felt a score should be a story-telling device: in other words, each character had a theme and when a character was on screen, that theme worked. If two characters were on screen at the same time, one tried somehow to work the two themes together. It was a totally Wagnerian concept of what film music should do; I don’t personally happen to agree with that. It seems to me that the story should work by itself and the finest thing that film music can do is somehow to emphasise (or supply) something that is implicit rather than explicit. In other words, to add an extra dimension. I mean, just simply to follow the story is not to do a tremendous service to the film. The story is, after all, self-evident. But perhaps some of the motivations of characters, their emotions, are not so self-evident.

Have there been any directors with whom you've been able to sit down and have musical discussions?

Yes, I would say so. There are several different kinds of directors, though. DeMille could dictate to you what he wanted, but stylistically. John Sturges is not a musician but he loves music and has a tremendous amount of enthusiasm - a unique way of being able to sit with a composer and just enthuse him with the character of a picture. Nothing to do with music - just in a general way what he wants. I always enjoyed our relationship. George Roy Hill, on the other hand, is an accomplished amateur musician and he can discuss what he wants in the music in fairly concrete terms; one feels much more that one is dealing with a colleague in purely musical terms. Alan Pakula - I’ve never worked with him as a director but I have as a producer - he has tremendous sensitivity in dramatic areas and we would talk for hours in terms of what we wanted to accomplish. On the negative side, though, there have been many directors and producers - especially in modem times - who have a very curious lack of sensitivity as to what music can do for a film - sometimes almost an animalistic fear of music. Not so much a fear of music as of emotion in general; they tend to want to keep the film fairly sterile. I’ve met this problem a great deal recently.

Quite by-the-by. talking about George Roy Hill, did you write the deliberately awful piano concerto in THE WORLD OF HENRY ORIENT that Peter Sellers performs?

No! I scored the film but a fellow called Kenneth Tauber wrote that. It’s a wonderful piece. He’s a very gifted writer and I don’t know why his career hasn’t gone further. Kenny Tauber wrote it before a composer had been hired for the film. I wish I had written it, but I didn’t!

How did you get on with the Music Directors of the great studio days?

As a matter of fact I rather enjoyed that system. Morris Stoloff, for instance, was very helpful to me at the beginning of my career in just giving me guidelines for what to aim for stylistically, what the parameters were, the lines beyond which it was not wise to go. Alfred Newman … when I did my first picture for him, he was helpful; I would certainly not consider it interference. He gave me tremendous support. The same thing with John Green.

How about the people in charge of sound effects?

Well, I’ll tell you about that. We’re talking here about the whole dubbing process. The people to blame here are the producers or directors, not the sound people. My relationships with sound men have been excellent, because we really help each other to a very great degree. There are times when the sound people need help; they lean on the music. It’s much more difficult to convince the director and/or producer that if, say, you’re going to have a terrific car chase with great revving of engines and squealing of brakes and shooting and God knows what else, and a score going like sixty with a vast symphony orchestra rattling away, they will cancel each other out. One must make a choice. We have a diabolical thing going on on the West Coast called ASI. It’s a preview theatre where people are literally dragged off the streets and put into this viewing room where they’re wired for blood pressure and all that sort of thing, and their reactions are charted. Well, obviously anyone knows that if you make a loud noise one’s blood pressure will go up; unfortunately these people begin to equate this with excitement. So producers tend to load tracks with too much, in which case everything loses, or go the other extreme, which is very fashionable also, and be quite sterile as far as sound and emotion is concerned. That’s the Skylla and Charybdis of our trade ...

Has a film ever contained more or less music than you wanted?

Most often! Well, I haven’t been forced to put more music into a film than I wanted; but there have been instances where music I’ve written has been used, after the fact, in areas where it was not intended. It’s rare, but it does happen sometimes. At the other extreme, taking the three films of mine shown last year - that's THE SHOOTIST, FROM NOON TILL THREE and THE INCREDIBLE SARAH - all three have only about half as much music in them as I thought they should have had.

So you yourself have never had occasion, say, to write an elaborate fugue and have it covered later by sound effects?

Oh, yes! Don’t misunderstand me; this happens all the time. There’s a tremendous amount of recomposition done by producers and directors after the fact. The music you write is, after all, a property of the producer - like a piece of furniture - and if he wishes to make cuts or anything he is perfectly within his legal rights. The composer has no come back on that. A shocking percentage of scores that anybody does are altered in some way - most often to their detriment. Therefore I would warn your readers that if one day they go to a picture to hear a score by somebody they otherwise respect but hear something which makes them think the composer has gone mad, like as not there’s a producer's hand in it somewhere.

*Editor’s note: Elmer Bernstein recorded Rozsa’s

The Thief of Bagdad with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Saltarello Choir at Olympic Studios, London, during January 1977. The original album, FMC-8A was released in 1977 (later reissued on Warner Bros Records BSK 3183 in 1978). Three other albums were recorded by Bernstein over the period 1978-79: SCORPIO (Jerry Fielding, FMC-11), LAND OF THE PHARAOHS/GUNFIGHT AT THE O.K. CORRAL (Dimitri Tiomkin, FMC-13) and THE HIGH AND THE MIGHTY/SEARCH FOR PARADISE (Dimitri Tiomkin, FMC-14). Bernstein planned a recording of Hugo Friedhofer’s THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES, to be orchestrated by Christopher Palmer, but the project was dropped.