The Ghost of Hans J. Salter

An Interview with Hans J. Salter by Preston Neal Jones

Originally published in Cinefantastique Vol.7 / No.2 / 1978

Text reproduced by kind permission of the author Preston Neal Jones

The man who brought harmony to the House of Frankenstein

Beginning in the 1940s, rival studios would send for prints of Universal's horror films so that they could study one element which helped make pictures like THE WOLF MAN, HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN and SON OF DRACULA so successful. Which contribution did these studios most want to analyze and emulate? Was it Jack Pierce's monstrous makeup? The convincing performances of Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney? The imaginative direction of Robert Siodmak and Roy William Neill? The colorful scripts? The eerie settings? The atmospheric photography? Each of these factors had its indispensable place in the creation of Universal’s product. But the reason so many studios wanted to view these champion horror movies was so that they could study one unique ingredient of Universal's magic recipe: the musical scores of Hans J. Salter.

Salter has written hundreds of scores for every type of movie-drama, comedy, swashbuckler, western, musical, mystery, historical epic - and he has been nominated six times for an Academy Award. Yet it is the opinion of many, including this writer, that Salter's masterwork is his contribution to the sagas of the Universal bogey men. When Lon Chaney breaks through his straps in THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN and lunges for Cedric Hardwicke, Salter's orchestral decension down the tonal scale evokes a brutal inevitability which seems to propel the Monster's attack. When a condemned Chaney walks the last mile as the MAN-MADE MONSTER, Salter creates a touching funeral march for the procession. The composer achieves a similarly telling effect in FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN as the villagers carry the dead girl through the street, a march scored subtly and poignantly by Salter within a mere forty-five seconds of screen time. Earlier in that same picture, as the moonlight creeps through the hospital window toward Larry Talbot's bed, the unsettling weavings in Salter's score convey the dark mystery of this seemingly ordinary occurrence. And when Chaney, as Talbot, sees the moonlight and turns his face away, Salter's string section tells us all we need to know of Talbot's torment. But Salter brings the same skill to scenes requiring a lighter touch from the definitive “old spooky touch” music in Abbott and Costello's HOLD THAT GHOST to the scherzo that enriches the scene of Chaney playing with his dog in MAN-MADE MONSTER. Along with the actor and the director, Salter is the third force in providing characterization, from the eerie shepherd's horn theme for Bela Lugosi's Ygor in THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN, to the tender violin solos for Elena Verdugo's gipsy girl in HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN, to the melancholy themes that haunt Lon Chaney in all of the Wolf Man films, an elegy, not for the dead, but for one who wishes that he were dead.

These movies were made in the years before sound track record albums became an important part of the musical market-place, and in recent years Universal has joined in the barbaric Hollywood practice of throwing written scores into the junk-heap to make room for new files. For the time being, therefore, the only way the public can enjoy this music is by hearing it on the Late, Late Show, mixed in with the dialogue and sound effects. A small portion of Salter's fantasy music survives in the archives of a northwestern university, where may be found sheet music from such later productions as THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN and THIS ISLAND, EARTH, plus one precious relic from the golden years: an old sixteen inch record which the composer has labelled “The Ghost of Hans J. Salter,” containing selections from THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN, including a few themes originally used in THE WOLF MAN and MAN-MADE MONSTER.

Born in Vienna in 1896, Salter had conducted in opera houses and silent movie palaces - including performances of Fritz Lang's WOMAN IN THE MOON - before writing music for early talkies at the famous U.F.A. Studios in Berlin. The coming of Hitler led to an exodus which eventually brought Salter to Hollywood in the late 1930s. The chance to score one scene in THE RAGE OF PARIS (1938) led to a career at Universal, though his chores during the first few years included not only composing but also scrutinizing the play-back synchronization of Deanna Durbin musicals and orchestrating the scores of other composers, such as Frank Skinner. Both composers are given co-screen-credit for THE INVISIBLE MAN RETURNS (1940), and MAN-MADE MONSTER (1941). The battle of Hollywood composers for artistic and financial recognition has always been an uphill struggle, and neither Salter nor Skinner received official screen credit for their contribution to the landmark score in 1941's THE WOLF MAN. Although the hectic deadlines at Universal's film factory sometimes necessitated the assistance of such fellow composers as Skinner and Paul Dessau, Hans J. Salter was the creator of most of the music for Universal's horror classics of the ‘40s.

My first meeting with Mr. Salter is arranged to take place at an outdoor restaurant on Sunset Boulevard. For the two and a half months that I have been in Hollywood, not a drop of rain has interrupted the warm, eternal sunshine for which the town is famous. But as I approach the rendezvous with Mr. Salter, the air is for the first time cooled and darkened by forboding clouds. I am beginning to wonder whether the composer is bringing with him the sinister weather that always hovered over the graveyards, castles and forests at Universal, when I catch sight of Mr. Salter himself, smiling in greeting, sunshine incarnate.

He is a pro. He is quietly proud of the genuine accomplishments of his long career, yet he clearly has a sense for the humorous side of his years at Universal. Although his life's work has been spent in shaping the medium of sound, he makes no sound when he laughs. While his vocal chords remain silent, his head nods, his eyes become cheery crescents and his smile beams fully. During the course of our lunch, his talk drifts to the early days at Universal, and he finds it hard to keep a straight face when discussing the distinction he has earned as composer for their horror films.

“Do you know what they used to call me in those days?” asks Mr. Salter, starting to laugh. The Master of Terror and Suspense! Pretty good? They couldn't understand how a nice, mild-mannered fellow from Vienna could develop such a sense of horror and mayhem. You know, I still get letters from people asking about those scores. This is very surprising, this renewed interest in the scores of the ‘40s. Why is it?”

I suggest that very few present-day films offer scores of the same type or quality. “In those days,” says Mr. Salter, “we had no idea we were writing for ‘eternity.’ We were just trying to keep up with the frantic pace of picture after picture. Let’s say it was a Monday, the producer showed you his picture. You had to write a score, and orchestrate it, and be ready to rehearse and record with the orchestra on the following Monday. It was like a factory, where you'd have to produce a certain amount of red socks, a certain amount of green socks. They'd screen one of those pictures for us without the music, and it would be nothing. All the pictures we saved for them! But those executives, they never knew what they had. We never heard a word from them. They were afraid if they gave us a compliment we'd ask for a raise.”

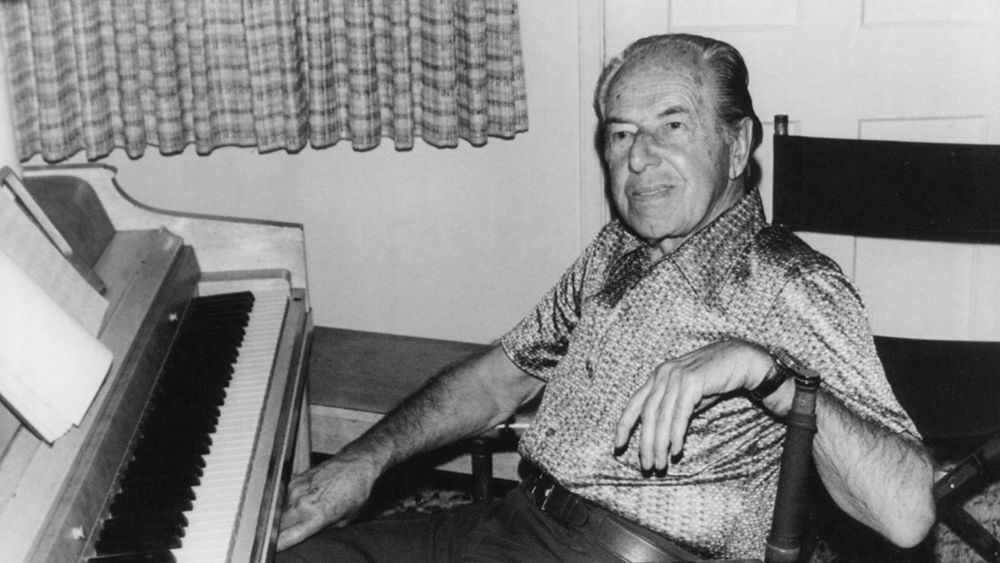

A week later, amid the fall of leaves, I carry my tape recorders up the driveway of Mr. Salter's home, not far from the studio where he worked for more than a quarter of a century. Mr. Salter shows me to his study and, as I prepare the equipment for our interview, I look around. Here is the piano on which Mr. Salter wrote much of his music. And over there are some of the fruits of his labors: two shelves full of bound conductor's scores, including INVISIBLE AGENT, HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN and THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN. Just beneath a row of Academy Award Nomination certificates is a set of sound equipment, upon which Mr. Salter has prepared a surprise. Without saying anything, he pushes a button, a tape starts turning, and the wall speakers fill the room with the mournful music of men singing in a strange language. One word, however, turns out to be recognizable: “Ananka.” It is the ancient funeral chant of the slaves who buried Princess Ananka in THE MUMMY'S HAND. Mr. Salter lets the tape play a few more minutes and I recognize themes from MAN-MADE MONSTER, BLACK FRIDAY and the mounting brass crescendo with which Lou Costello discovered, in HOLD THAT GHOST, that his bedroom had been suddenly changed into a gambling casino. We have been listening, Mr. Salter explains as he stops the tape, to a few minutes from “The Salter Rhapsody,” the only other surviving recording from his horror movie era.

About those movies, Mr. Salter expresses mixed feelings. He has said that the music was usually on a much higher level than the pictures, yet he will say at one point in the interview that the horror films will probably outlast most of the other movies to which he contributed. When I ask him to name his own favorite Salter scores, he names such pictures as BEND OF THE RIVER, a James Stewart western directed by Anthony Mann, THUNDER ON THE HILL, a Claudette Colbert mystery directed by Douglas Sirk, and, especially, THE MAGNIFICENT DOLL, an historical drama with Ginger Rogers and David Niven, directed by Frank Borzage.

I notice you haven't mentioned any of the horror pictures.

Those horror pictures were a big challenge to me. When they presented those pictures to me in the projection room, there was nothing there, just a bunch of disjointed scenes that had no cohesion and didn't scare anybody. You had to create with the music all the horror, all the tension that was “in between the lines” and didn't come off on screen. And that was such a tremendous challenge that these pictures interested me, and I developed a very refined technique for this type of picture. But, as far as giving me a personal thrill, I can't say that they did. (Salter smiles.) Sorry to disappoint you.

You had no special affinity for the fantastic subject matter in the horror films?

I must have had, because I mastered it in a short time. The musical devices at my command were evidently right at the right time and the right spot. And I know, whenever a picture of this type was done at another studio, they always ran for their composers one of my pictures, to show them how to treat it.

In some of the horror films there were moments which could have been used in a “straight” dramatic picture, such as the last mile walk in MAN MADE MONSTER, or the more melancholy passages in THE WOLF MAN. Would you, perhaps, have felt as moved by these as you were by some of your “straight” scores?

My basic approach to pictures is always the same. I ask myself, “What did the director want to tell the audience with this scene? Where does the picture, or the scene need help?” Very often, I've told producers that they didn't need music for this scene, and they disagreed with me violently. There was a producer, who shall remain nameless, who showed me his picture, PHANTOM LADY (A Cornell Woolrich mystery with Franchot Tone and Ella Raines), directed by Robert Siodmak, and he said that he wanted a lot of music in it. I told him, “All you need is a main and end title. The picture plays just the way it is. You'll have a big success.” He argued that they needed a lot of help with this scene, and this, and this... I said, “Well, you’re the boss, so I will write it, but it's just a waste of money, because in the dubbing room (where dialogue, music and sound effects are blended into the final sound track), you'll take out all this music.” Okay, I wrote it, and, as I predicted, in the dubbing room, he took out the music for first this scene, then this, then this... The picture went out with just the main and end title. Half a year goes by, and the same producer has another Siodmak picture, UNCLE HARRY. (A murder-suspense story with George Sanders.) He says, “In this picture, we won't need any music. I've already used up the music budget for other things, bigger sets, better actors, and so on.” He shows me the picture, and it was a real lemon. And I told him, “Sorry to contradict you, but this picture needs an awful lot of help.” He said, “You are really crazy! One time, you tell me I don't need any music, now you tell me I need a lot of music! You're wrong, and I'll tell you what we'll do. We'll take it out to a preview with just main and end title music, and then we'll release it that way.” So they took the picture out for a preview that way and it must have laid a big egg because the next morning the producer called me and said, “I need a hundred percent score!” He had to go to the front office on his hands and knees and beg for money for the music budget. I gave the picture, I would say, at least sixty percent music. The producer saw his picture and it was like - (Salter raises his hands and eyebrows in wonder) - he was so amazed. That's the way it went out.

When we first met, you were talking about the frantic, assembly-line pace at Universal. Did you, like most film composers, have to use an orchestrator to meet those deadlines?

Yes, whenever there was no time for orchestrating it myself. I started out as an orchestrator for Frank Skinner. I orchestrated for him one of those early Frankenstein pictures, SON OF FRANKENSTEIN. I remember, there was one stretch, pretty close to the recording date, where we didn't leave the studio for forty-eight or fifty hours. He would sit at the piano and compose a sequence, and then he would hand it to me. I would orchestrate it and he would take a nap on the couch in the meantime. Then, when I was through orchestrating, I would wake him up, and he had to go back and write another sequence while I would take a nap. And this went on for forty-eight hours or so, so that he could make the recording date.

That was one of Skinner's finest scores. Was it written in just those couple of days?

No, no, not a couple of days. But I don't think we had more than maybe two weeks to write the whole thing. There was always a release date staring us in the face, and my friend, Charlie Previn, who was the head of the music department, would aggravate the situation by saying, “They want this picture on Thursday. Let's show 'em! We'll give it to them on Wednesday!” He was a bachelor, and he couldn't understand how some of us with wives and families might actually have some kind of a life away from the studio. He was a charming fellow, and I was very fond of him, but sometimes he just drove us nuts with these things.

TOWER OF LONDON was also released in 1939, had Rathbone and Karloff, as Richard III and his executioner, supported by the same music as in SON OF FRANKENSTEIN.

I remember TOWER OF LONDON very well. What we tried to do there was to record music of that period, John Dowland and other early English composers' music, without regard to the scene, just for sort of a mood. And we used harpsichord, and flutes and viola da gambas - all those old instruments. But when we went to the preview with this, it didn't work out. The executives were somehow startled. They didn’t like it. They couldn't make heads or tails out of that sound. I think I had orchestrated some of that old music for strings and harpsichord, and I think I wrote a few sequences, too, in that style. It was a good idea, but it didn't work. So, after the preview, all this music was replaced by some other music, and some of it was from SON OF FRANKENSTEIN.

You, yourself, would sometimes re-use parts of your scores in other films.

It was a matter of necessity, sometimes. When we were behind the eight-ball with these recording dates and there wasn't time to write a completely new score, I would use bits and pieces of scores written by myself or my colleagues for other pictures. Charlie Previn called this process “Salterizing.” I would try to create something that would be on an equal footing with a complete new score. And I'm sure that ninety percent of the people didn't know the difference.

Graveyard - The opening music from the first scene in FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN was one of Salter's most atmospheric creations, and one which made many felicitous reappearances in such subsequent Universal thrillers as SON OF DRACULA, HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN and others. (© 1943 Universal Music Corp.)

At the factory that was Universal, did you have any voice in choosing which pictures would be assigned to you?

They made, in those days, an average of about seventy-five pictures a year. So, you can divide two men into seventy-five, and what do you arrive at? In those days, everybody had to work on practically every picture. And the credits rarely reflected the whole story.

In TOWER OF LONDON, Previn is credited with the score and Skinner only receives credit for “Orchestrations,” even though most of the music was his. And Previn receives the only music credit on THE WOLF MAN.

Once in a while, Previn wrote a sequence, too. He had that ambition to keep his hand in the pie. (Universal no longer has any of the written score from THE WOLF MAN, but a list of that film's music cues gives credit to Salter, Skinner, and Previn, sometimes individually, sometimes collectively.)

Just how would you and Skinner collaborate on such a score?

We would split it up. Let's say, I would tell Frank, “I'm going to write this theme, and this theme, and this theme, and you write this theme, and this theme.” And then we would exchange them, and use them as close as possible to their original form, and that would give the whole score a certain cohesion. We each tried to write in a style that was not too far apart.

How would you decide on that style? THE WOLF MAN is a film score very much of-a-piece.

This can only be described in musical terms. We would stay within the bounds of tonality, so to speak, and not try to write anything too complicated which would stick out like a sore thumb. And, since we thought along more or less the same lines, musically… Maybe I was a little ahead of him in certain respects.

Such as…?

Maybe in harmony, or in melodic development. If I held myself back a little, and he progressed a little, then we would meet somewhere in the middle. Frank Skinner was a real pal. He was such a wonderful fellow, so dependable. I don't think they make them any more like they did in those days, because Frank was, in many ways, a self-taught man. When I came to Universal in 1937, he was actually just learning the trade, so to speak. He had been a dance arranger before that. He came out of a dance band himself. I think he was a trombone player. How he adapted himself, with this limited knowledge, to write music for films, and to see how he grew with every assignment was wonderful to watch.

You say one of your first Universal jobs was orchestrating his music?

Yes, and then later on he orchestrated some of my music when it was necessary. When I first met him, he was not very talkative. He must have had some kind of inhibitions. He didn't open up easily to another person. But once you were his friend, you couldn't ask for a better friend than he was. He was very warm. He had a certain aura about him that was really wonderful. He would do some sequences in pictures when I couldn't get through in time. Frank Skinner was always there to the rescue, like the Marine.

Did he ever tell you what he considered his finest score?

No, I can't remember that he ever did. There were some pictures that he was fond of. (Salter smiles) But the Frankenstein pictures were not among them.

Many people regard THE WOLF MAN as a milestone score, and yet, neither you nor Skinner had any special feeling for it at the time…?

No. I don't think anybody who created the basic material for a film like this, not even writers or directors, had that feeling at the time. Only time can tell if it has any lasting value. And I, personally, think that the horror films of that period will survive everything else. It's such a valid piece of Americana that it'll overshadow, not the westerns, but all the romantic comedies, the adventure stories, and so on. And this will survive into the twenty-first century, more than anything else. Because, it was such a unique piece of work that couldn’t be duplicated, no matter how hard they try. And it has retained its flavor to such a degree that, in spite of dated costumes and dated style, it still remains a valid piece of work. And, it was such a good wedding between music and story and direction. I think film music, per se, is an art form, and the horror picture, per se, is an art form, and the wedding of these two elements created something unique.

There is much music in your scores which is complete in itself. In MAN-MADE MONSTER, Lon Chaney plays with his dog and there's a delightful scherzo with a beginning, a middle, and an end...

I always tried to do that, write set-pieces that made sense within themselves, if the scene required it. It was always my endeavor to write music that made sense as music and, within the flow of the music, to accentuate certain aspects of the film. But generally speaking, it's the wedding between the picture and the music that gives it that unique value. In picking my favorites from among my own scores, however, I can only judge by the way the music affected me while I was recording it on the stage. Some of the scores are just more or less a routine job, although I am happy they work out the way I had planned. But at other times the music affects me very deeply, and it gives me an exhilarating thrill, something that you can't get with any other endeavor. The laws that govern the flow of a scene, visually, and the laws that govern music, aurally, are diametrically opposed, and to bring these two disciplines in unison is not easy. Sometimes it made me cry, to see how well the music fitted the scene, how much it did for the scene or lifted the picture to some new heights that it didn't have before. I just couldn't believe it. Maybe other people were not affected the same way, but for me as the creator to see how all the musical devices I planned worked out to such perfection and improved what they had on the screen was a very big thrill. It's a unique feeling to get back what you have put in. Even in the horror scores, some of the sequences affected me deeply.

In looking through your copy of the HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN score, I find a section which must have been written for Boris Karloff and J. Carroll Naish's stormy exodus from prison, called here “The Gruesome Twosome Escape.” That certainly indicates a less than reverent attitude...

(Salter smiles) Yes, that was a great hobby of mine, developing those titles.*

I notice, just before that sequence, a short section by yourself and Frank Skinner called “Lightening Strikes.” And I see you share writing credit on many selections with “Paul Dessau.” Who was he?

Paul Dessau, a very talented man. It was one of those cases where there was very little time, and I needed some help to meet the recording date, so I called on him. He worked very fast and very well. I knew him from Berlin. He's a well-known opera composer now, in East Germany.

Did you work with him in the same manner as with Skinner on THE WOLF MAN?

It was similar. I would lay out themes for certain situations and certain characters in the film, and we would both use the same themes, only develop them differently. I discussed every sequence with him, how I would have done it, and then left it up to him to use his own musical language. But still, it created a certain unity and cohesion in the score, and it sounded like one composer. If you organize it right, and work it out, then it's bound to culminate in a good score.

On a film like HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN or THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN, did you work with director Erle C. Kenton or with his producer?

With Kenton. Kenton was a routine director. He was nothing particular. He was very matter of fact, and he left everything musical up to me. He had no opinion.

How about his HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN producer, Paul Malvern?

He was the same kind of fellow, sort of a minus-B producer, you know? This was just a routine job for them. I don't think they had any particular love or feeling for these fantasies they were making. They trusted me and I was pretty much on my own.

How about director Roy William Neill?

Neill? He did most of those Sherlock Holmes pictures, and FRANKENSTEIN

MEETS THE WOLF MAN. He impressed me at that time as a better grade director. But I don't recall that he expressed any likes or dislikes. He accepted pretty much what I gave him.

Did a fellow like Erle C. Kenton ever thank you for what you had done?

Oh, yes. And George Waggner, director of THE WOLF MAN, he appreciated it very much. I think he wrote the lyrics for that “Faro-La, Faro-Li,” the song in FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN. (Producer-director Waggner did indeed write lyrics for Universal, but studio records reveal that Curt Siodmak, author of the screenplay, wrote the lyrics in this film. Incidentally, a 78 pm recording of this musical number still exists in Mr. Salter's private collection.)

Yes, that's the villager's song about death and eternal life which so upsets Larry Talbot. Was that actor singing to a playback of his own voice or someone else's?

Oh, that was his own voice. I can't remember that actor's name, but he was

making several movies in those days. He was a very pleasant fellow. He was a Russian gipsy by heritage, and when we pre-recorded this song he just ate it up. He loved doing it.

Do you have any recollection of Rowland V. Lee, producer-director of SON OF FRANKENSTEIN and TOWER OF LONDON?

Very charming fellow. A typical yankee. He embodied the best things in America. He had a wonderful sense of humor, and a wonderful outlook on life which was very heartening. While we were working on his pictures, Frank and I sometimes had lunch with him in the commissary, and he was always a lot of fun.

Elegy for the Undead - A few bars from the “Queens Hospital” cue in FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLFMAN show a fragment of the theme Frank Skinner originally wrote for “Bela's Funeral” in THE WOLF MAN. This plaintive motif was “Salterized” into the scores of all three of the Wolf Man sequels. (© 1943 Universal Music Corp.)

Fritz Lang's SCARLET STREET isn’t one of his fantasies, but it was a bizarre murder story. Was that your first association with Lang since conducting a score for him in the silent days?

Yes, and we became very friendly again. As a matter of fact, even long after the picture was finished, we used to eat lunch together in his office. He brought his lunch and I brought mine, and then he gave me half of his and I gave him half of mine, and it was a surprise every day, what we would bring. He told me a lot about his early days, and about some pet projects of his that he couldn't get anybody interested in producing. He was a very sophisticated, very intelligent fellow, and he had a strong feel for music in making pictures. Lang was basically an artist. He'd wanted to become a painter, originally, and then later he got into films. But he had the eye of a painter, and also a certain affinity for all other arts through that. So, you could talk to him in artistic terms and he understood what you were trying to do. And I can see how some people might find him hard to get along with, but he certainly has made his mark on the history of film.

Did you find him hard to get along with?

No, not the least bit. The only disagreement we had - not exactly disagreement - was a long discussion about the ending of SCARLET STREET. It was one of the first films in those days that ended downbeat.

The film has a haunting ending, with Edward G. Robinson trudging off into the snow, haunted by the voices of Joan Bennett and Dan Duryea, the people for whose deaths he was responsible. How did you originally plan on scoring those last moments?

Well, very similarly to as it finally was. But at the very end, I wanted to go up a little more, and leave some ray of hope for the man. Musically, it seemed more natural - to develop it, and then end on a rise and a final redemption. But Lang didn't buy that. He said, “If we did that, it would defy the whole idea of my picture. This has to be downbeat, all the way to the very last frame.” And he convinced me he was right. That's the way I scored it. Goes out, very sombre to the very end, and just a few finishing chords, and that's it.

You scored two films produced by Val Lewton, unfortunately after his series of horror pictures. Did you work with him or with his directors?

I only dealt with Val Lewton, and it was a joy working with him. Such a wonderful fellow. He was a very literate guy, and he had a very highly developed sense of humor. PLEASE BELIEVE ME was at MGM and, to my surprise, he appeared a year later at Universal, and he asked for me. I did something interesting for him in APACHE DRUMS. The main title is nothing but drums, running against each other in counterpoint. I recorded it on five different tracks and then combined them into one.

Had you discussed the idea with Lewton?

Oh, sure, he loved it. And with a title like APACHE DRUMS, you couldn't ask for more. Another interesting development - I think it was this film, but it may have been some other western that I did. There was a war chant in it, Indians dancing around the fire, so they had the brilliant idea to call in real Indians to do the prerecording. Now, when these real Indians come in, none of them could speak any Indian dialect. None of them. They were real Hollywood Indians. I said, “We can’t do it this way,” so, what I did was I invented an Indian language. I did some research, studied different dialects from the part of the country where the picture took place. I wrote the chant and the dance that accompanies it, and I put these Indian words into it. And then I called back these Indians, but I added about eight good voices, because these Indians had no voices, they were just mumbling. (Salter smiles) And then, I, the guy from Vienna, the master of suspense and terror, taught these Indians how to sing in Indian!

How about the funeral chant in THE MUMMY'S HAND - did you have to do research on that?

(Salter laughs) That was pure unadulterated Salter! Right from the tap! I had to get an extra provision in the budget to hire the eight vocalists for that sequence. I always liked to dress up certain scores with unexpected ingredients like the human voice.

I have a tape here of selections recorded from the sound tracks of a few of your horror pictures. According to the Universal cue sheets, you wrote the main title to THE INVISIBLE MAN RETURNS, introducing the motif which receives many varied treatments throughout the score. Perhaps the loveliest variation occurs in the final scene when Vincent Price regains visibility and is reunited with his beloved. (Playing tape) Skinner shares credit with you on this sequence. This was a long time ago, of course, but can you recall which contribution was yours and which was Skinner's?

The only thing I can say is that probably only those last three or four bars were Skinner's tacked on to the rest of it. But I think it's all mine up to the point where it goes into that apotheosis at the end. It sounds like a good piece.

When you Salterized SON OF DRACULA, you used the same piece but for a totally different, unhappy ending. You superimposed a solo violin, which made a lot of difference. Now, in these selections from THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN, the theme Ygor plays on his shepherd's pipe at the beginning takes many forms, for many different purposes, in the background scoring throughout the picture.

At the time, it seemed a logical idea to devise a strange-sounding theme for Ygor’s horn that could also be used and enlarged in all kinds of disguises and fashions in the rest of the score.

Frank Skinner took a similar approach in SON OF FRANKENSTEIN, using an instrument called a blute for the sound of Lugosi's horn.

Mine was an English horn. It's probably that lowered fifth that repeats itself - da-da-da-da-da - which gives it that particular flavor.

For the opening graveyard sequence of FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN, as the ghouls approach the Talbot crypt, you wrote one of your moodiest themes. Is that an organ playing the melody over those low strings?

It's a novachord. These string chords are based on fourths, which have a strange quality. Usually, chords are based on thirds, but these are based on fourths - there's a fourth interval between each voice. When you move these chords back and forth it gives a special, eerie and mysterious feeling. And then, if you put on top of it an eerie-sounding melody line with the novachord, it really adds up to something very strong.

When the grave-robbers break in and remove the wolf-bane from Larry Talbot’s corpse, the moonlight filters in and we hear the theme which will accompany the moonlight and warn us throughout the film whenever Talbot is about to become the Wolf Man.

There is a celeste in there, high strings, and high woodwinds. It's the interplay between these three elements that creates that effect.

Your scores are usually very melodic, even in the most horrific passages. But when that animal hand grabs slowly for the thief's wrist, you merely build a few slow chords that are so low-pitched they're almost more sound effect than music. The effect is chilling. How did you achieve that unique sound?

That's the novachord again, but in a low register which is very rarely used. Most people use the instrument for melody line, higher, or screaming chords, higher. But that low register has an ominous quality. (As the tape plays the scene of Talbot’s transformation in the hospital) Boy, oh boy. All that music that I've written. I never realized it!

How does it sound, being heard the first time in over thirty years?

Pleasing. I'm very critical of my own music. And if I hear, after thirty years, that I was on the right track even then, that gives you a good feeling.

After handling all the major Universal horror films, including all the Wolf Man and Frankenstein pictures, why didn't you serve as musical director on the last of the series, HOUSE OF DRACULA, in 1945?

In all probability, I simply wasn't available. I must have been working on another picture at the same time. We composers were like taxi drivers. As soon as we finished one job, we grabbed the next fare that came along and then we were off.

In the 1950s, you participated in the science fiction boom at Universal through your contributions to the scores of THIS ISLAND, EARTH and THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN. Do you recall working with producer William Alland or director Jack Arnold?

As far as my work was concerned, Alland's contribution was a minor one compared to Jack Arnold's. Arnold was a very congenial man. We would discuss the scoring and we pretty much saw eye-to-eye on the approach. That SHRINKING MAN was a very interesting project. In scenes where his size reduced, we weren't able to work from the final product because the special effects team was still working on it, so we composers had to use our imaginations and score our own fantasies. The music cutters told us the rate of the character's reduction (for the climax) and how many seconds it would take, but that was all. But this was typical with a special effects picture; we often had to revise our scores or shorten them after the effects were finished. On those Invisible Man pictures we never had the finished product to work with. That was understandable, because John Fulton took great pains to see that every effect would come off as he had planned. We composers never saw the final product until the preview. I remember how mad I used to get when, after working frantically day and night to meet a certain recording date, Fulton still took his good time-maybe a week or ten days-before he was ready for the preview. I could have used some of this time to very good advantage.

I believe that Herman Stein and Henry Mancini scored all of the early portions of THIS ISLAND, EARTH and that your work was on the cataclysmic finale, with the planet blowing up and the mutant running amok...

I usually inherited the “colossal” sequences.

Although you wrote some melodic passages for THE CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON, your scoring of the Creature and the Metaluna mutant in THIS ISLAND, EARTH was strikingly discordant, more so than for the Frankenstein or Wolf Man pictures.

I can only tell you that what is right for one picture is not necessarily right for another picture. I tried to write music that would be appropriate for those particular scenes.

What are your feelings about this year’s highly successful science fiction scores by John Williams, STAR WARS and CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND?

It really is not fair to compare the two scores. I like them both. Of the two, I like STAR WARS more, because it contributed more to the picture. In CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, however, I liked the final scene in which music became an integral part of the story. I thought that that was a very fine touch.

Do you have any recollections of the late Bernard Herrmann, whose fantasy scores have gained renewed interest in recent years?

I'd prefer not to discuss my memories of him. “De mortuis nil nisi bene.” But I must say, he was a very talented man. I liked his early scores more than his later ones. His CITIZEN KANE was a landmark, a real breath of fresh air. Later, I think, he seemed to go off on a tangent as though he thought his music was more important than the picture, and this got him into a lot of trouble. PSYCHO was good. Not all the way through, but some of it was great. But in some pictures he started using outlandish orchestrations. It was as if he had the faculty of cutting out the director when they were discussing what kind of a score was needed. He would seem to be listening to the director but he listened only to himself. This is just my impression, however; I never discussed it with him.

Are you familiar with Rozsa's classic fantasy scores for THE THIEF OF BAGDAD and THE JUNGLE BOOK?

Oh, yes. Of all the film composers, I would say that Miki is in a class by himself. He has developed his own unique style which is highly recognizable, and he has kept his high standards. He is really the only one of us who has managed to maintain a film career and still fulfill himself in the concert field.

Before you came to Universal, the studio had been blessed by distinguished scores by Heinz Roemheld for THE INVISIBLE MAN and, especially, by Franz Waxman for THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN. Might they have any influence on your work in the horror genre?

I did not meet Roemheld until much later. I studied his score for THE INVISIBLE MAN at the Universal library, because I was looking through all the scores, but it made no indelible impression that I can recall. I thought Franz did very well with his score for THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN. I saw the film before coming to this country. But Franz and I knew each other from the very beginning when he was playing the piano with a German jazz band. I always thought he was a very fine composer. But when I came to Universal, he was with MGM, so the pictures of his which we discussed were for that studio. His Frankenstein score was not really an influence on me.

What sort of compensation did Universal offer their composers? Were you paid per film, or per week, or what?

For a composer, that can work in one of several ways. He can be paid a weekly salary, or on commission, or by a package deal in which the composer acts as an independent contractor, not only writing the score but hiring the studio and the musicians and gambling on his own talents to get through in time - otherwise the overtime comes out of his own pocket. In my case, I started at Universal with a weekly salary which increased every year until I left in 1947 to work on a free-lance commission basis. I came back to Universal in 1950 and signed a three-year contract. After that ran out, l worked freelance again, on a flat weekly salary with a three-to-four week guarantee.

And were you ever paid when your music would be re-used, without screen credit, in later Universal films?

No. Once they paid you for the original assignment, they were free to use your music again and again, run it backwards, or mutilate it in any way they saw fit. A composer like Jerome Kern or Richard Rodgers could make arrangements for future credit and remuneration for his work, but we miserable plebes never had that chance. Congress passed a new copyright law in 1976 which corrected some of these inequities.

Often the music credit would merely say “Musical Direction by Joseph Gershenson…”

When more than two composers contributed to a score, only the music director got the credit. I conducted most of my own scores, but when Gershenson came in, he liked to conduct sometimes. He would conduct, and I would sit in the control room and tell him what was wrong.

So it was wrong more often than right?

Well, naturally. I know better what I want to express in a sequence than he does. He was a good technician, but he had no sensitive feeling for what was in the music itself, sometimes he missed the meaning completely. So I had to tell him what was the idea behind this or that, and he would agree and do it the way I wanted.

Do you receive residuals when your films are shown on TV?

I get something from the three networks. That is, they pay a sum to ASCAP once a year for the use of their whole catalog, and this is divided among the membership. We get nothing from the independents. I try to let ASCAP know when I see one of my pictures on an independent station, but there is no regular survey basis to keep track of these things, so there is no proof that the ASCAP material is used. There are many inequities in this business. Because of the United States' medieval copyright laws, the studio, and not the composer, is the “author” of his own music. There was a time when even ASCAP refused to pay film composers special compensation for their work. Revenue from film showings used to go into the pot for distribution to the whole ASCAP membership.

You've spoken of Universal as a factory and of the pressure to meet release dates. About how much time would usually elapse between your pre-production discussion with the producer and his showing you the rough cut of the film?

That differed. Sometimes they were in trouble or they had bad weather, so it took longer to shoot it and longer to cut it. But at the end of it was always a release date they had to meet. So the longer they took to cut a picture the less time would be left between that point and the release date, and the people to suffer would be composers and sound-dubbing men, because these had to be squeezed together. Instead of one week, maybe in three days or so. On the average, it would take at least six weeks after pre-production discussions before they would show me their film.

After which you would run the film a couple of times for just yourself?

And then started a fight for the film. Because, in those days at Universal, each one of these departments wanted to have the film to work on it, and there was only one copy available. Later on, when they made color films, they made a dupe in black and white for us to work on. But in the early days, everything was black and white, so this was the only copy that was available. So the sound department would call up and say, “I'll give you Reel One if you'll give me Reel Six.” And two hours later they said, “Okay, you can have Reel Six, but now we want Reel One back.” And you couldn't make any marks on this film because this was to be the copy that was taken out for a preview later on.

How many instrumentalists did the budgets allow you for your orchestra?

For the horror pictures, something like thirty men.

Did you have to employ any technical tricks to get those thirty to sound like the larger orchestra we seem to hear on the films' sound tracks?

Oh, sure, you'd have to orchestrate in a way that hid all the weak points in an orchestra. Let's say you have only six violins. If you just let the six violins play, it sounds thin. But if you double up the six violins with two flutes and two clarinets and an oboe and bassoon, it hides it somehow. It sounds fuller and it takes on a different coloration altogether. Then there was the placing of the mikes and balancing certain parts of the orchestra against the rest of it. And in the dubbing you could help, too, by adding more to the lower end or the higher end of the frequencies on the sound track, according to what was necessary.

On a recording day, how much time would be allowed to rehearse before recording?

(Salter laughs) Very little. The less the better, because time was money. You had to write it in a way that the musicians could read it without difficulty, rehearse a few key spots that were a little harder, and then you would go for a take right away. Sometimes one sequence would be six minutes long, which would be too long to record. If there was a mistake at the end of six minutes you would have to go back to the beginning and record the whole thing all over again. You had to have one take that was immaculate. So you would break the sequence into two or three pieces which would segue one into the other. Even then, there could be problems. I remember one instance where I had already made a take on one sequence and the moment the red light was off the film's cutter rushed in and said “Hold everything! We just made another cut!” So he showed me the cut. I had to discard the whole take, make a cut in the music, and then record it. Things like this happened quite often. Rarely was a picture really finished when I got it.

Although such madhouse conditions no longer plague Mr. Salter, he remains musically active. Until recently, the Salter representations on commercial recordings was meager and in no way reflective of his stature as a film composer. Salter has always maintained his good humor about such inequities. When a film-music publication recently paid tribute to Salter and other “Obscure Film Composers,” Salter was amused to note that he was in good company, as the list included Aaron Copland; and for a time Salter would occasionally refer to himself as “that obscure composer.” Recently, however, what amounts to a Salter renaissance has begun to redress the balance. “The Master of Terror and Suspense” is appearing with increasing frequency in print, in person, and, most importantly, on records.

In the spring of 1977, the UCLA Extension and Filmex (the Los Angeles Film Exposition) cooperated in presenting a series in which film composers showed film clips of their work and discussed their art with the audience. Author / producer Tony Thomas, the series' coordinator and host, organized each evening around a single theme. The program devoted to “Fantasy, Horror and Science Fiction” featured Salter, Jerry Goldsmith, Leonard Rosenman, Jerry Fielding and David Raskin (presenting a tribute to the late Bernard Herrmann in addition to discussing his own scores). Following a screening of the first reel of FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN, Salter, with his customary good humor, answered questions from Thomas and members of the audience. Afterwards, the composer's fans gathered around him seeking his autograph and the answers to further questions.

Shortly after the Filmex / UCLA celebration of film music, Tony Thomas' Citadel Records issued MAYA, the first LP devoted solely to a complete Salter score. Citadel soon followed this Salter television score with another, WICHITA TOWN. Yet perhaps Citadel's most important Salter record is the third and latest: The Horror Rhapsody (back to-back with the John Cacavas score for HORROR EXPRESS). Subtitled by Thomas “Music for Frankenstein, Dracula, The Mummy, The Wolf Man and Other Old Friends,” the album presents selections from Salter's earliest efforts in the genre, (before, in fact, he had met a couple of the notorious gentlemen listed in the subtitle) including a few pieces discussed in this article, and incorporating references to some of Frank Skinner's themes. A glorious musical surface has at last been scratched, and it is to be hoped that The Horror Rhapsody is but a harbinger of more horror to come. (In the early '60s, Coral Records issued a Themes From Horror Movies album, conducted by Dick Jacobs and including music by Salter, Mancini, William Lava, Herman Stein, James Bernard and others. Of the four Salter selections, all but one was played and recorded abominably and / or smothered in superfluous sound effects. The French MCA label has recently reissued this disc, without the sound effects, according to one source.)

As to the scoring of films, Salter describes himself as “practically retired. These Producers,” he says, “now want to get rich quickly on the music. They're not interested in helping their pictures. It's an entirely different ball game now, and I’m not going to contribute to that.” Does he, however, still write music? “I'm working on a trio for piano, violin and cello, and also an orchestral piece, sort of a suite of about four or five movements. I hope to have two movements finished within a short time. I'm taking my time. I'm in no hurry. That's not like writing for the movies, where you have to be ready on Thursday.”

Acknowledgements: For permission to reproduce portions of scores by Salter and Frank Skinner, the author wishes to thank Mr. Harry Garfield of the Universal Music Department. For countless acts of kindness during the research process, the author thanks Mr. Irwin Coster of the Universal Music Library, and Library staff-members Ms. Patricia Glass, Ms. Gladys Johnson, and Ms. Masia Massett. Gratitude is due Mr. W. A. (Al) Skinner for the photograph of his late brother Frank. The author is grateful to Dr. Gene Gressley of The University of Wyoming for the supply of both research material and encouragement during this project. Further thanks go to Ms. Elizabeth Allensworth for technical assistance. Above all, the author thanks Mr. Hans J. Salter for his time, for patience, for his good cheer. For his photographs, for his words - and his music.

* It was a hobby shared by Mr. Salter's colleagues. Selections in Frank Skinner's score for ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN include such titles as: “Franken Skinner's Monster,” “Out-Monstered,” and “Dracula Hits the Jackpot.” Long before PETER GUNN, Henry Mancini's titles for THE CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON include “Something's Fishy.” and “Who's Stalking Who?” Heinz (THE INVISIBLE MAN) Roemheld contributed to THE MOLE PEOPLE such punning pieces as “Nasty Crack,” “Hello Statue,” and “Sandy Claws!”