A Conversation with Akira Ifukube

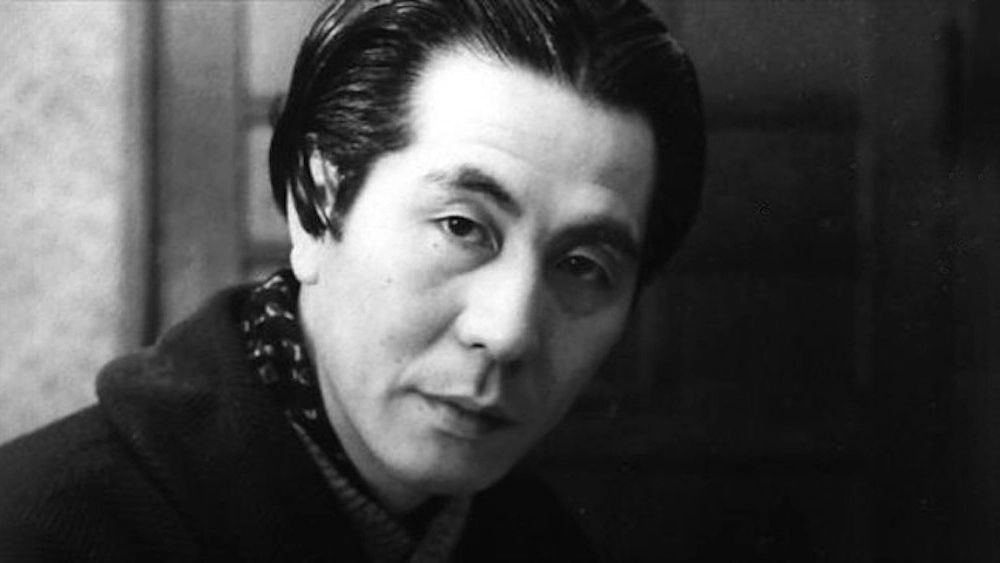

A Conversation with Akira Ifukube by Wolfgang Breyer / Translated from Japanese by Sachiko Tonegi

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.12 / No.50 / 1994

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

The following interview took place at Mr. Ifukube‘s house (in a garden-city district of Tokyo) during my concert tour with the “Wiener Johann Strauss Orchestra” in January 1991 and January 1993. As a collector of antique samovars and tea pots/cups, Mr. Ifukube personally served us traditional Japanese green tea, which is a great honor for foreigners visiting Japan. We all had a wonderful afternoon in a warm hearted atmosphere and I feel very proud having been able to talk to one of Japan’s most famous composers – an artist with a great sense of humor.

What can you tell us about the history of film music in Japan, from the beginning, in the silent film era?

The first film music in Europe appeared in THE ASSASSINATION OF DUKE GUISE by Saint-Saens in 1908. The first film music in Japan was made to provide the sound effect when a cellist threw his cello! It had much sound but no sense. Only in Tokyo we had small string orchestras and many organists. The first composers of Japanese film music were Noboru Ito, Shiro Fukai and Ryoichi Hattori, who is also famous for popular music.

In Japan we learned the Russian, American and European styles of film music. The Russian style: a composer composed film music after reading a script but not having seen the movie. American style: many composers sold their themes and music scored to the music director or publishers, who chose the music for each part of the movie. So it was unbalanced music on the whole. European style: Film music was composed after the composer saw the movie. So the audiences were impressed with the music. In Japan we borrowed the European style. We composed film music after we saw the rushes. When I first started I composed film music without seeing the rushes. For example, when I composed a love scene at sunset, I imagined long shots of lovers, but actually the film took close shots of them. So I could not express the atmosphere.

What was your family background, your education and how you got into film composing?

I was born in Kushiro/Hokkaido and I first majored in forestry, so I was a forest engineer before World War II. Also I studied music at the University and became a good violin player performing as a soloist with my great friend Fumio Hayasaka accompanying me on piano. At a concert in Sapporo in 1934 I was the first musician in Japan to play Erik Satie. During the War I made a design of an airplane for the GHQ but when we lost the War I also lost my job. So I became a musician. Some of my concert music was performed in Paris and other places. After the War I was also a professor at Tokyo Geijutsu University, for one year. But I could not live on a small salary, so I lived in Nikko for a while. And I came back to Tokyo to compose my first film music, GINREI-NO-HATE (To the End of the Silver Mountains) in 1947.

What has influenced you musically? Do you have some favorite composers?

The Russian composer Alexander Tcherepnin has influenced me the most. With one of my concert works I won the first prize in an ‘A. Tcherepnin Contest’ in Europe and after that I studied with him in Boston. He was also responsible for the premiere of my first ballet, ‘Bon Odori / Bon Dance’. It was performed at Vienna in 1938. I’m still very proud of it. I also like Stravinsky, Manuel de Falla and Mussorgsky. In film music, I am influenced by Jacques Ibert and Alexander Tansmann. I had a close friendship with Alexander Tansmann and we exchanged letters but the War stopped all that. I am also influenced by opera, especially Verdi. The spirit of my movie music is from an operatic style.

When you score a film does the director influence your decisions?

I always like to meet the director before shooting starts. A director does not order me to do anything, but I try to grasp the meaning of his ideas during the discussion. I have always had a free hand when composing.

Do you have a personal philosophy about film music?

I always think that film music can establish four things: At first, it can establish the situation of time and space. The second, it can excite the emotion that the film expressed. I think there are two types of excitement – one is “interpunkt” – I compose sad music for a sad scene; the other is “kontrapunkt” (counterpoint) – I compose joyful music for a sad scene in contrast with the sadness. Thirdly, it can indicate the sequence. For example, in the first scene a fisherman is drowned at sea. In the next scene, his wife and child play at the beach and know nothing about the accident. So I continue to play the same music from the sad scene to the peaceful scene to show that it’s one sequence. Fourthly, it can embellish the photography. For example, if a rose is blooming in high speed, the picture does not need any music, essentially, but I’ll add music because I want the audience to feel the atmosphere of that growing rose. Screen music should not explain – screen music should express expressions.

What is your opinion about the character of good film music?

I think that a movie consists of three parts: dramaturgy, photography and music. You see, sometimes the story is strong, sometimes the camera work is strong, sometimes the music is strong. I consider that it is not good to treat these three parts equally. For example, if you have a dinner, you will start to have hors-d’oeuvre, soup, main dish, dessert and coffee. If you mix all these dishes you will have a nasty taste and you won’t enjoy your delicious dinner. We experience the same thing in a movie. After you finish seeing it, you will feel the harmony of all three parts.

In 1954 you were hired to write the music for Inoshiro Honda’s first giant monster film, GODZILLA. How did you get involved in it?

I really don’t know why the film company chose me as the composer of GODZILLA. I guess, because GODZILLA is big and I like big things and at that time I composed for and conducted a big symphony orchestra. Maybe that was the reason!

I read that you composed your famous GODZILLA music before you ever saw the film. Is that true?

Yes, that’s true. I only saw the model of Godzilla and I read the script. In Japan, in most cases a composer has only one week’s time to compose film music after the film is finished. I didn’t have enough time, so I composed my Godzilla music before I saw the film.

How did you get the idea to use a march theme as a leitmotiv for the monster?

I don’t remember – but the sound of Go Dzi La resembled the musical scale Do Si La – but I decided to use the minor mode key. I really don’t remember – I just thought it was good and striking. When GODZILLA first appears on the screen they needed strong music – just his horrifying face would not be enough.

You scored only one film for Akira Kurosawa. Is there a reason you never scored another film for him?

I worked with him on SHIZUKANARU KETTO (The Quiet Duel) in 1948-49. At that time, I felt something strange about his script – it seemed unnatural to me. It’s about a doctor who, during an operation, becomes infected with syphilis from a patient. I told him it’s an unnatural, stupid story and then we never worked together again. We didn’t have good feelings for each other, either.

In 1953 you wrote the music for the Viennese-born Hollywood director Joseph von Sternberg…

(Enthusiastically) Yes, yes, of course ANATAHAN!

Would you tell us your impressions about this famous director, about the film and his understanding for music?

That was really a fantastic experience. He was such a gentleman. ANATAHAN (The Saga of Anatahan) was actually his last film – he did it for himself, and as an insult to everyone else – especially Hollywood. This film was his swan song – he was such a pictorial stylist. I discussed a lot of things with him and at the beginning it was rather difficult for me as a Japanese to understand his foreign mentality and all its fine nuances. I tried to work hard with him and I played all the different themes on the piano for him. The whole movie was full of music except only five minutes. So I had to compose a lot of music – actually one reel a day, so I completed my work in ten days. He requested that I use Asian instruments. I had, and still have, a collection of very old Chinese instruments (300 years old). So I taught the musicians how to play them. Mr. Sternberg also liked mysterious moods, so I also used the Japanese instrument, Koto, which was played by a blind musician. This caused some problems because when I conducted the orchestra the player could not see me, so I had an assistant behind him who patted the blind player’s shoulder when he had a part to play. It caused a little time lag, but Mr. Sternberg liked my music very much and accepted the time delay. It took four days to record the music, which was composed in a European style mixed with Asian orchestrations.

The third well-known director you have worked with is of course Inoshiro Honda, the director of GODZILLA. How do you see your relationship with him?

Again, I talk about everything with him ahead of time, and he always gave me a completely free hand. When he visited the recording studio he never said anything, but it was his idea to accomplish Godzilla’s famous roar musically. I loosened the strings of a double-bass and pulled them with resin-coated leather gloves; then we slowed the speed and tried other things, and that gave us Godzilla’s roar. For the sequels, Mr. Honda used my recorded music quite a lot because it saved us time. I always felt a shortage of time to compose music – especially in the film business. Therefore I am not very satisfied with my film music, but I am glad I got into movies and I learned a great deal about orchestration.

That means you see yourself not as a film composer, but more of a composer for the concert hall?

It is the form which I think is the most important element in concert music. As you know, film music has no form. I am not satisfied with my film music because of a lot of the limitations. So I try to express my ideas in concert music. But my film music is popular with people while my concert works are not so well known. I still work hard to compose for the concert hall. Once I retired I became President of Tokyo College of Music about 15 years ago. I retired as President and now I teach composition. In 1978 I retired from film music after having scored LADY OGIN. Just for fun – and because so many fans asked me to do it – I wrote the music for two new Godzilla sequels, GODZILLA VS KING GHIDRA and just recently GODZILLA VS MOTHRA. The kids still like it!