King Kong

Parmi les grands mythes originaux que le cinéma a produits, il convient de placer KING KONG au premier rang. Bien que l'histoire s'inspire de «La Belle et la Bête» le personnage même du gorille géant est une création du vingtième siècle contrairement à Frankenstein ou Dracula. Comme tous les films mythiques, KING KONG a donné lieu à des dizaines d'interprétations différentes : économiques, politiques, sociologiques, philosophiques ou psychologiques.

Et comme tous les films à succès KING KONG a entraîné une avalanche de suites, d'imitations et de remakes. Mais ni SON OF KONG ou MIGHTY JOE YOUNG ni GODZILLA n'ont pu exercer cette fascination. Le remake de 1976 prouve encore combien il est vain de vouloir imiter un tel film. Comme si quelqu'un essayait de refaire la Joconde ! Cette comparaison, qui peut paraître outrancière, montre néanmoins le fond du problème : ce film a une âme qui résiste à toute analyse et qui ne se laisse pas recréer. Dans cet article, nous ne pouvons analyser qu'un des éléments de KING KONG parmi les plus importants la musique de Max Steiner.

Le film

KING KONG est essentiellement l'œuvre de Merian C. Cooper, l'une des personnalités les plus extraordinaires du cinéma américain. Avant KING KONG COOPER s'était déjà distingué par deux documentaires, GRASS et CHANG, réalisés en collaboration avec Ernest B. Schoedsack.

L'histoire originale avait été conçue par Cooper et l'écrivain anglais Edgar Wallace, qui mourut lors de son travail sur le film. Le scénario fut élaboré par James Creelman et Ruth Rose : le film fut produit et dirigé par Merian C. Cooper et Ernest B. Schoedsack.

Les effets spéciaux étaient l'œuvre de Willis O’Brien. Le procédé d'animation des «monstres» était simple mais efficace : de petites maquettes dotées d'articulations métalliques étaient placées sur une table ; chaque phase de leurs "mouvements" était photographiée séparément, de façon à donner l'illusion d'un mouvement continu lors de la projection à vitesse normale. Ces maquettes étaient intégrées ensemble avec les personnages réels dans une jungle expressionniste qui n'a pas son égal dans l'histoire du cinéma. Le décor est en fait un des éléments essentiels du film.

Le tournage durait 18 mois. D'après Merian C. Cooper le film aurait coûté 430.000 dollars. Lorsqu'il fut présenté à New York, il fit gagner 89.931 dollars en quatre jours à la RKO, qui s'était déjà trouvée au bord de la faillite. (1)

La musique

En 1933 Max Steiner était le chef du département musical de la RKO. De 1929 à 1933, il avait arrangé et composé la musique de plus de cinquante films. Le plus souvent, son travail se limitait à composer de courtes pièces pour le générique et la fin du film, ce n'est qu'avec SYMPHONY OF SIX MILLION que Steiner réussissa à démontrer la valeur dramatique que la musique peut prendre dans un film. C'était en 1931. En 1932 Steiner composa la musique de BIRD OF PARADISE et THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME. Mais c'est avec KING KONG que Max Steiner commença un nouveau chapitre de l'histoire de la musique de film. La musique était désormais un élément vital du film ; personne ne demandait : «Mais d'où vient cette musique ?», comme l'avaient craint les producteurs au début des années trente.

Steiner raconte que, lors du montage de KING KONG, le président de la RKO B. B. Kahane lui fit part de ses doutes concernant le succès commercial du film. Il lui recommanda d'utiliser des bandes disponibles dans la librairie musicale du studio, afin de ne pas faire augmenter encore plus le budget du film. Steiner, horrifié par cette idée, reçut de l'aide de Merian C. COOPER, qui sentait probablement lui-même que quelque chose manquait à son film. Il pria le compositeur de faire de son mieux et de ne pas se soucier du budget ; c'est lui, Cooper, qui payerait l'orchestre et subviendrait à toutes les autres charges. À la fin, le budget musical s'élevait à 50.000 dollars, une somme prodigieuse en 1933.

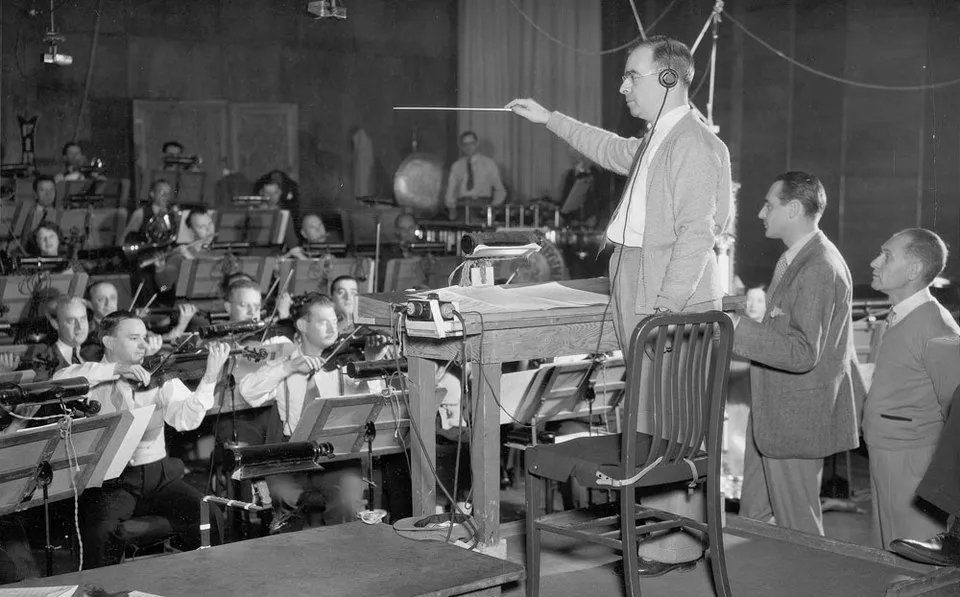

Steiner commença la partition le 9 décembre 1932 et la compléta huit semaines plus tard. (2) L'orchestration fut élaborée par Bernard Kaun. Max Steiner lui-même dirigea l'enregistrement de sa musique.

Une opinion courante veut que Steiner ait utilisé un orchestre symphonique de 80 pièces, ce qui est peu probable. Fred Steiner, se basant sur des vérifications effectuées dans les archives de la RKO à Los Angeles, affirme que Max Steiner n'a pas utilisé plus de 46 musiciens lors de l'enregistrement de la musique. (3). En fait, les orchestres permanents des grands studios n'avaient presque jamais les dimensions d'un orchestre dit «symphonique» (80 pièces environ). Au début des années '30, un orchestre de 46 musiciens semblait absolument prodigieux !

Après l'enregistrement de la partition, les effets sonores furent adaptés à la musique, afin de rendre la bande sonore plus efficace. (4)

Des extraits de la bande originale furent réutilisés dans un certain nombre de films RKO : SON OF KONG, THE LAST DAYS OF POMPEII et plusieurs autres, Steiner lui-même reprit certains extraits de sa partition dans A STOLEN LIFE, WHITE HEAT, DISTANT DRUMS et SO BIG.

Sur les 104 minutes que dure le film (la version complète étant rarement montrée en Europe) il y a environ 75 minutes de musique. La partition accompagne donc à peu près 3/4 du film.

Commentaire de la partition

La musique de KING KONG se fonde essentiellement sur l'emploi de leitmotivs. Le leitmotiv est un bref thème musical associé à un ou plusieurs personnages, un lieu géographique ou bien une idée abstraite. Il doit pouvoir s'adapter aux différentes situations de l'histoire, tout en restant parfaitement reconnaissable. Dans KING KONG Max Steiner, utilise plusieurs motifs, qui répondent à cette définition.

1) Le thème de Kong : Le thème principal du film est un exemple parfait de leitmotiv. Il est extrêmement court et facilement discernable. Trois notes chromatiques suggèrent la force énorme de Kong et la peur qu'il inspire.

Malgré sa simplicité, ce thème peut être varié de manière à exprimer des sentiments tout à fait opposés. Il caractérise d'abord la force du gorille géant (lors de son apparition et de ses victoires sur les autres monstres), sa majestuosité voulant signifier que Kong est vraiment un «roi» dans son île. Le thème souligne aussi la colère de Kong lorsqu'on lui a arraché Ann (Kong enfonçant le portail gigantesque ou se libérant de ses chaînes).

Dans la dernière partie du film, il acquiert une dimension dramatique nouvelle. Lorsque Kong grimpe sur l'Empire State Building, son thème, joué sombrement par les cuivres, semble indiquer sa fin tragique. Touché mortellement par les avions, Kong prend Ann une dernière fois dans sa main géante. Nous entendons une variation déchirante de son thème ; lorsque Kong tombe, la musique semble se dissoudre littéralement. Le spectateur en arrive presque à éprouver de la sympathie pour le monstre, une idée que les images seules n'auraient pu communiquer.

2)

Le thème de Ann Darrow : L'héroïne du film est caractérisée par un thème qui a nettement le caractère d'une valse viennoise.

Dans sa forme originale le thème est surtout utilisé lorsque Ann se trouve en compagnie de Jack Driscoll ou des autres membres de l'expédition. En fait, il sert aussi comme thème d'amour pour Ann et Jack (scène sur le bateau).

À ce sujet, il est intéressant de noter que Steiner n'utilise aucun motif particulier pour Jack Driscoll, ce qui est tout à fait conforme aux intentions du scénario.

Une version chromatique du thème de Ann apparaît dans la scène du sacrifice. On remarquera que les trois premières notes correspondent à celles qui forment le thème de Kong ce qui n'est probablement guère un hasard.

Par la suite, il suggère la peur qu'inspirent Kong et les autres monstres à la jeune fille. Ce thème caractérise aussi l'amour qu'éprouve Kong pour Ann. Dans la scène finale, ou Kong prend Ann une dernière fois dans sa main, la musique ne souligne pas l'horreur de la situation, mais plutôt la tragédie de cet amour impossible. La musique aide, ainsi à expliquer la phrase finale du film : «It was Beauty that killed the Beast !».

3) Un troisième 'leitmotiv' important est associé au courage et à l'audace des membres de l'expédition. Il apparaît chaque fois que les hommes sont menacés par les dangers de l'île, pour symboliser leur volonté de continuer et de sauver Ann en dépit de tous les obstacles.

Ce thème est associé plus particulièrement à Jack Driscoll lors de ses efforts pour sauver Ann. Dans la première partie du film, il est souvent présenté de manière telle à suggérer l'impuissance des hommes devant les monstres gigantesques de l'île. Dans la scène où Jack essaie de blesser Kong avec son couteau, Steiner paraphrase le motif du courage avec chaque coup de couteau comme pour montrer la vanité de cette entreprise. À part ces trois thèmes principaux. Steiner utilise encore un certain nombre de motifs secondaires, présentés ici dans leur ordre d'apparence.

1) L'île est caractérisée par un thème à la fois majestueux et sinistre, constitué par une suite de notes ascendantes touées par les trombones. La musique aide à créer immédiatement une atmosphère de tension et de menace invisible, lorsque le bateau s'approche de l'île. Ce motif est utilisé aussi lors de l'enlèvement de Ann et lors de la scène du sacrifice pour suggérer les menaces venant de cet endroit de cauchemar.

2) Les aborigènes sont représentés par un bref thème répétitif qui apparaît surtout dans la scène du sacrifice pour accentuer la sauvagerie et le fanatisme des indigènes. Ce thème réapparaît brièvement dans la scène où Kong enfonce le portail gigantesque et se met à détruire le village.

3) Lorsque Denham, Driscoll et les matelots entrent dans le village (après l'enlèvement de Ann), un thème agité représente l'affolement des hommes confrontés à l'horreur de la situation. Dans la scène du radeau, Steiner réutilise ce motif pour souligner la peur qui se saisit des hommes poursuivis par un énorme brontosaure. Il apparaît une dernière fois après que Ann a été enlevée par Kong dans sa chambre d'hôtel à New York, pour souligner la consternation de Driscoll et de Denham et la panique qui se saisit d'eux.

4) Une marche mystériouso paraphrase l'avance prudente des hommes à travers la jungle et suggère les dangers qui les guettent ; dans la scène du brontosaure, ce thème, transformé totalement, accompagne la fuite paniquée des hommes devant le monstre gigantesque. Il représente aussi l'attente angoissée des hommes restés dans le village. Bien que ce motif soit essentiellement lié à l'expédition pour suivant Kong dans la jungle, il réapparaît dans les scènes à New York, tout comme le thème précédent, pour souligner le fait que le cauchemar se répète.

La partition de Max Steiner est basée principalement sur l'utilisation de ces 'leitmotivs'. Les plus importants sont le thème de Kong et celui de Ann, qui sont d'ailleurs souvent juxtaposés. Après avoir analysé les différents thèmes, on doit nécessairement se poser une question : comment la musique fonctionne-t-elle par rapport aux images ? Et à un niveau plus général : quelle est la fonction de la musique dans un film fantastique ?

En simplifiant, on peut dire que plus que dans un autre genre de films, la musique fonctionne au niveau du subconscient. Son rôle est d'abattre la résistance du spectateur à tout ce qui est surnaturel, en intensifiant l'impact Immédiat des images. La musique force le spectateur à jouer le jeu, à croire ce qui est incroyable.

La partition de Steiner constitue en fait un des principaux supports du film. La musique n'est pas greffée sur les Images, mais elle naît naturellement du rythme et de l'atmosphère du film. Ceci explique que la plupart des spectateurs ne se rendent pas compte de la musique quand ils voient KING KONG ; images et musique forment un tout indissociable.

À ce sujet, il est intéressant de noter que la partition n'accompagne pas le film de bout en bout, comme on le croit parfois. Steiner avait suggéré de laisser les séquences "réalistes" à New York et sur le bateau sans musique. Ce n'est qu'après vingt minutes que la musique est introduite dans la scène où le bateau, perdu dans la brume, s'approche de l'ile. Le spectateur a l'impression d'un voyage dans l'espace et dans le temps, d'une transition entre le monde réel et le monde du rêve. De là, la musique accompagne presque tout le film plongeant le spectateur dans un long crescendo d'horreur.

Souvent, la partition a aussi un rôle explicatif. Souvent, la partition a aussi un rôle explicatif. Elle constitue une interprétation des événements suivant l'idée principale du film : "La Belle et la Bête", idée qui n'apparaît pas à travers les images seules (bien qu'elle soit parfois évoquée par Carl Denham).

Cette utilisation de la musique caractérise surtout la fin du film. Ainsi dans la scène où Kong grimpe la façade d'un bâtiment et enlève une femme dans sa chambre. L'emploi du thème de Kong aurait été évident pour suggérer l'horreur de la scène. Mais Steiner utilise une variation chromatique du thème de Ann, qui suggère la colère et la déception de Kong lorsqu'il voit que ce n'est pas Ann qu'il tient et qu'il laisse tomber la femme. Et quand Kong, blessé mortellement par les avions, prend Ann une dernière fois dans sa main, la musique ne représente pas la peur de la jeune fille ; mais une variation déchirante du thème de Ann suggère l'amour et le désespoir du gorille géant. Lorsque la foule curieuse se rassemble autour du cadavre de Kong. Steiner unit une dernière fois son thème à celui de Ann.

Importance

Comparée à la musique de films fantastiques plus récents. La partition de Max Steiner est moins un élément d'atmosphère que de rythmes. KING KONG est certainement une des partitions les plus modernistes de son compositeur. Par ses qualités rythmiques, elle fait penser au "SACRE DU PRINTEMPS" de STRAVINSKY, tandis que par l'orchestration, elle se rapproche plutôt de Richard STRAUSS et de Gustav Mahler (respectivement le parrain et le professeur de Max STEINER). C'est partiellement grâce à "KING KONG" et à Max Steiner que le style symphonique et l'utilisation de 'leitmotivs' réussissaient à s'imposer dans la musique de film hollywoodienne.

Pour comprendre l'importance de la partition de Max Steiner, il convient de la placer dans son contexte historique. Ray Bradbury écrit à ce sujet : "Il m'est difficile de croire, comme le font certains, que sans Steiner KING KONG aurait été un micmac ridicule. Mais il est évident que si vous enleviez la musique de Max STEINER et y substitutiez le traitement habituel du début des années trente, consistant en un tambour, deux flûtes et quatre violons, vous pourriez en faire la comédie du siècle." (5)

L'âme de Kong, ne serait-ce donc pas la musique de Max Steiner ?

Notes:

(1) John W. Morgan, Liner Notes, "King Kong" (Entr'acte ERS-6504)

(2) id.

(3) Fred Steiner, Liner Notes, "King Kong" (Entr'acte)

(4) John W. Morgan, 1d..

(5) Ray Bradbury, Steiner Out of Kong by Cooper, "King Kong" (United Artists UALA-373-G)