So much has been written about Hollywood's classic film composers from the Golden Age: Max Steiner, Alfred Newman, Bernard Herrmann, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Victor Young, David Raksin, Franz Waxman and others. But what about the people in the orchestra, the studio musicians? Without them, the music written by these composers would fail to come alive. You can't travel just by staring at a map.

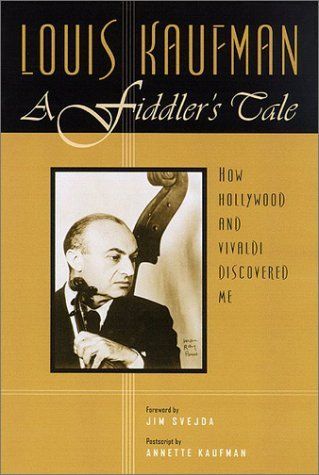

I had the extraordinary chance to get to know one of old Hollywood's foremost concertmasters at film scoring sessions: Louis Kaufman and his lovely wife Annette. Louis was one of the great American violin players of our century. He always performed and recorded pieces apart from the mainstream violin literature, for instance Sam Barber's Concerto for Violin and Orchestra. op. 14, Darius Milhaud's Second Violin Concerto (with Milhaud himself conducting), Walter Piston's Violin Concerto No. 1 (with Bernard Herrmann conducting the London Symphony Orchestra), Aaron Copland's Violin Sonata and Nocturne (with Copland at the piano).

So it was only a matter of time before Louis came to Hollywood and played his beloved instrument for all the film composers mentioned above. The list of films - altogether more than 500! - which benefitted from Kaufman's warm and spirited string performance is impressive: LAURA, SAYONARA, CLEOPATRA, THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN, REBECCA, SUSPICION, CAPTAIN BLOOD, THE SEA HAWK, CASABLANCA, PSYCHO, THE RED PONY, PINOCCHIO, GONE WITH THE WIND, WUTHERING HEIGHTS, SINCE YOU WENT AWAY, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD, to name just a few.

Born in Portland, Oregon, on May 10, 1905, of Romanian-Jewish parents, Louis later-made his first recordings for Thomas Edison. When he was seven years old and on his way to school, Louis heard someone playing the violin. The player became his first local teacher. Six months later Louis played better than his teacher! Before he could actually read music he got his first prize for a performance, a three dollar bill. "From then on my father was convinced I was a genius."

At age 13, Louis went to New York to study for eight years at the Institute of Musical Art (which was later absorbed by the Juilliard School). He studied with Franz Kneisel who was a friend of Johannes Brahms. Says Kaufman, "Kneisel was very harsh, very intolerant. But I had enough sense to stick to him." He graduated in 1927 and won two awards, the Loeb Prize and the Naumburg Award. After a while Louis was invited by all the great players to play with them: Mischa Elman, Jascha Heifetz, Fritz Kreisler and others. Together with his new wife Annette - they were married in 1933 - Louis started to play programs for radio stations in Portland, San Francisco, San Diego and Denver. They went to Los Angeles, and the city made the most wonderful impression on the young couple. Louis played three programs a week at KFI (NBC), earning $75.

One day MGM called, asking if he would play for Ernst Lubitsch's new film, THE MERRY WIDOW. The German director had heard one of his programs on radio. Kaufman said, "I don't know if I'm good for this commercial work. My background is very serious." - "Okay, we'll pay you double money." Louis agreed, without knowing how much the amount would be. In one week Kaufman earned 1500 dollars: "We have no choice, Annette. We've got to like this." In one year the Kaufmans saved enough money for their beautiful house in Westwood, built by Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1942, while working on THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, Louis and Annette became Bernard Herrmann's closest friends until his death in 1975. In 1948 the Kaufmans left Hollywood and went to Europe to extend their concert and recording activities. With Paris as their base they stayed in France for more than five years.

I spent an afternoon with Annette and Louis Kaufman at their home in March 1992, and I felt how close they were, with Annette being Louis' encyclopedic memory. I have rarely met people more friendly and caring than this lovely couple. When I went back to L.A. in March 1994, I was looking forward to seeing my two "old" friends again. Sadly Louis died on February 9, 1994, of congestive heart failure as a result of the big earthquake in January. He was 88 years old.

Louis, did you have any idea what Hollywood was like before you came here?

Louis Kaufman: Not at all. It was a new world. It was the Promised Land. When I came to MGM to work on Ernst Lubitsch's THE MERRY WIDOW, the conductor-composer Herbert Stothart introduced me to the orchestra, and I took my place on the first stand. Then I was very often called upon to do these solos. It wasn't too difficult. It was just long and tedious until the Union realized that it was too hard for the musicians to record sometimes way into the morning, after a full day's work. It had gone around like wildfire that I was there and played these solos. That's how we met Max Steiner, Alfred Newman, Bernard Herrmann, Franz Waxman, all those great composers.

Annette Kaufman: They were just starting out. They had a hard time trying to make producers realize that music had a certain place in a film. Essentially, when you look at a fire in a black-and-white film, - films were all black-and-white at that time - it isn't very exciting or particularly interesting with just the ordinary background sounds.

Did you appreciate film music, Louis, or did you look down your nose on this strange kind of music, in view of your classical background?

No. They were all great musicians. We had great respect. That was the Golden Age. People kept asking me, "How can you leave the world of New York and string quartets to go to this vulgar, common place called Hollywood?" - I said, "No one stops you from playing as well as you can, and the checks are always good." Hollywood was just not the sort of vision that many People have about our community. They always say rather snobbishly - perhaps in New York and Boston - that it's a cultural desert. That's all nonsense. Even when we came here for the first time, we had wonderful symphony concerts conducted by Barbirolli and Klemperer. In The Pasadena Playhouse they performed Shakespeare. So it was a wonderful atmosphere. It was a magnificent training ground for me, developing a discipline and listening to myself all the time via microphone. For instance, to play some of the modern works, it's silly to have the same approach that you have for playing Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn or Brahms. You have to create a different style. I could never have done some of the American material that incorporates popular idioms and even jazz with just a straightforward classic or romantic approach. It was challenging to evolve a style that would fit this modern material. Also, it was through Hollywood that I met some of the most important composers that I was able to work with: Aaron Copland, Darius Milhaud, Robert Russell Bennett, Ernst Toch, Bernard Herrmann. So I will always be thankful to Hollywood.

Let's talk about some of these wonderful musicians. Did you work with Max Steiner?

He had a wonderful melodic and harmonic gift. One of the most impressive examples of what music can do in the hands of a master like Steiner is OF HUMAN BONDAGE. I still remember the material. It sticks to your ribs. First they had just temporary tracks. The preview was disastrous. The audience was laughing all the time. The producers thought their investment was going down. In a panic they called Max Steiner who wrote a masterly score in something of a hurry. Then the audience laughed and cried at the right time.

Max called us up one Sunday morning, "Come over with your violin. I'm arranging the material for GONE WITH THE WIND. The piano might be a little dry for Selznick." Selznick was very fussy and a perfectionist in every detail, including music, which he knew very little about. Our presentation of Max's themes was submitted to Selznick who accepted the whole thing very enthusiastically.

Producers-directors on the one hand, film composers on the other hand, that's always a funny and sometimes a disastrous relationship.

Rudolph Polk wanted to help Ernst Toch to earn some money here. So he introduced him to Josef von Sternberg who was a very fine director but didn't know much about music. Von Sternberg walked to the piano when Toch was first introduced to him and played a middle C. He said, "This is the note I want you to use in your score." Toch just turned on his heel and walked out. He said, "I can't work with an idiot like that."

Ernst Toch worked on THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME at RKO. Newman conducted the score. For a scene when Charles Laughton as the hunchback is seen climbing up Notre Dame, Toch wrote a fugal treatment of his theme. It was a ten to fifteen-minute cue. We needed one day to record this. But Laughton refused the music since his grunts of effort couldn't be heard! So they had no music at all, which killed the excitement of the long climb.

You worked for Sam Goldwyn as well.

Yes. He made a picture called WE LIVE AGAIN (1934). It was based on Tolstoy's book "Resurrection". They had a Russian chorus and a Russian singer. Alfred Newman did a wonderful job with the orchestra. The sound-man was very upset at the time, because his wife was having a baby in the hospital. He was calling the hospital every few minutes to find out how she was, and he forgot to rewind the recording. Then Mr. Goldwyn heard it all backwards. The musicians in the orchestra didn't say a word. Goldwyn kept saying, "I never heard anything like it. It is absolutely great."

Did the composers or the conductors tell you anything about the movie in order to get the right feeling for the scenes?

No, it was sort of blind. We had plenty of time to get to see some sort of episodes, but the film was never shown to us in total. Generally speaking, the film industry was miles ahead of the recording industry. Newman was a special expert on sound. He knew exactly where to put the microphones. He was paying special attention to the strings because Al realized that they sound more human than woodwinds or horns.

What is the mystery behind the extra-ordinary and legendary "Newman string sound"?

It's a little bit like cooking. Annette sometimes cooks very delicious dishes that astonish our friends. She writes down the ingredients, but they never come out quite the same. Art essentially is a mystery, and it should be a mystery. There is no reason why it has to come down to common sense or to the fact that two and two make four. Sometimes two and two make four million. It depends on your point of view. Newman chose the musicians very carefully.

Annette: Max Steiner wasn't that dependent on individual players. He thought more in orchestral, symphonic terms. He didn't depend on that kind of super-performance.

Louis: Nevertheless, they were all unique in their ways. No one ever gave us the music ahead of time to look at. They weren't ready. They had to work in a panic, copy at the last moment, record at the last moment.

Annette: The orchestrators were exceptional musicians.

Louis: They had to be. Max Steiner could orchestrate better than anybody else, but he just didn't have the time. It's incredible what fine work was able to be done by these specialists under pressure. I never could understand it.

One exception regarding orchestration was Bernard Herrmann.

Yes. He insisted upon enough time to write and orchestrate every tiny detail by himself. Producers didn't like him because he got that much extra money. Orchestrators didn't like him because he took a lot of work away from them. We got to know him very well. In this house we had many educated discussions about art, English literature and many more topics. As a matter of fact, we exchanged residences occasionally. So Bernard Herrmann lived here twice. (Matthias is now busily kissing the carpet). He gave us his apartment in New York. In this house he wrote ANNA AND THE KING OF SIAM. He was inspired by our home because we had some Buddhas from Thailand and Cambodia.

Annette: In THE DEVIL AND DANIEL WEBSTER Herrmann did a very interesting trick with Louis' solos. He sort of re-recorded them so that it sounded like three or four violins. He loved all kinds of obscure composers. He had a very inventive mind. His struggle was that he couldn't bear stupid people. If he'd be at a party with people that bored him, he wouldn't talk to them. He rather would get a book and read. So he had a hard time in Hollywood. He was in the wrong milieu here. He was all right in England where they accept eccentric people. As a matter of fact, he had his biggest public success as a conductor in England.

You worked a lot with Alfred Newman: DODSWORTH, WUTHERING HEIGHTS, THE DIARY OF ANNE FRANK, THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD, among many more.

In WUTHERING HEIGHTS I had violin solos from beginning to end. Newman paid me three times. He loved chamber music. Very often we played chamber music in his home. He was studying at that time with Schönberg. Schönberg asked me to prepare "Verklärte Nacht" (Transfigured Night op. 4), that marvellous early string sextet. So I rehearsed carefully with my friends. We had a very nice party and played it for Schönberg. We thought we were doing it pretty correctly. I was astonished when Schönberg said, "Kaufman, it was all right, but let yourself go, play it much more romantically."

Annette: When you did MODERN TIMES with Chaplin who used to make up his own tunes, he wanted Mickey-Mouse music for laughs in the scene where Chaplin is telling the girl what their future life would be like. Alfred Newman said, "No Mr. Chaplin, you'll spoil the dream. It's really a dream." So Newman put Louis behind a screen with a microphone by himself and his muted violin. The orchestra played without a mute. They recorded a lyric passage, and the music kept the dream going. That was much more moving.

Did you ever get a credit in any movie?

Annette: In FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS Louis' name was on the record. That was the first motion picture score to put on records (in January 1950).

Louis: Victor Young said to me, "Tonight we're gonna record this score." I didn't have my best violin with me, but I had a good one that was adequate for what we had to do. Actually, the processors at that time weren't sharp enough. Sometimes it was just as well to have an instrument that gave you the color you wanted without these very fine sonorities which were very mysterious and not always easy to capture with the microphone.

Did you have to use click tracks?

Click tracks were very good for a while for making sure that they got the right tempo for chases and other scenes. But they got to be a little bit too mechanical. So the good composers abandoned it then to give it a human leeway. Sometimes too much electronics begins to get in the way of what you want to project in the music itself.

I'm assuming that the film orchestras were so good that you didn't need much time for rehearsals and takes.

Sometimes the very first take that you do after the rehearsal is the very best. You may miss a few little details here and there that you'd like to correct, but it's like a fat lady in a corset: you correct one thing, and then something else sticks out. You begin to lose some of the living spontaneity. What I began to learn from Hollywood was that you have to be very careful. You cannot permit yourself the liberty that you have in a big concert hall with air space which acts as a wonderful filter. If you are right next to the microphone, you don't have that space, so you must learn how to project the feeling or intensity you want, but be very careful because if you use a little bit too much pressure, the tone begins to be harsh and scratchy. That was also a magnificent discipline for me.

One never ceases to learn and to develop his craft.

That's right. I had the most marvellous development because here I was as a youngster, having a chance to play chamber music with some of the greatest people. Jascha Heifetz, for instance, was wonderful to play with. Essentially he was very simple. It was very easy to follow him. He never exaggerated or tried to be too sentimental, dragging the tempos. When he would take fast tempi, it was hard to keep up with him. Even when he was reading something for the first time, he was like a cat that landed on its four legs. He never missed anything. He was miraculous.

Annette: Matthias, you see, Louis' life was the violin.

Louis: I was honestly not at all interested in anything else. I thought it was fascinating to learn how to play this little instrument, but as you get older your interests expand into other areas of art. We can all learn something through art, you have to know your instrument, you have to know your craft, naturally, but nevertheless you have to try to widen your intellectual horizons. To quote King Lear, "Nothing comes from nothing."

Do you still play the violin?

No, I retired in 1984 due to an eye operation and a slight accident to my thumb. It's a paradox, these artists that insist upon playing or singing to the very end - long after they have seen their best time - usually get their highest fees. I wasn't altogether satisfied when I made my last recordings. When you have to struggle doing some of the simple things that come naturally, like a bird sings, that was the time for me to retire.

So since then I haven't played. But Annette and I have been much busier since then than before. We have so many interests. We have never been bored. We go to concerts, and Annette is writing my biography. (After Louis died Annette continued writing the biography, but it became more difficult for her - MB) Having lived through this whole crazy century, how do you see today's film business? Today you have either murder stories and the many different ways people can be assassinated, or you have car chases and cars that are piling up. Here you don't need any symphonic developments. That's redundant. You can do all that electronically. For the audience it's just as effective. The level of material on TV is not very high. The lower the level gets, the more money they can make.

You can really be very content with the life you've led...

Louis: I'm in a situation where everybody is a junior for me. God always seemed to smile on us.

Annette: Louis always said, "You can create good habits as well as bad habits. Why not adopt good ones?" He never smoked. Alfred Newman, an incessant smoker, died many years ahead of his time.

Louis: The only danger with my music is killing people through boredom. That's the only punishment I can mete out to people.