An Interview with Georges Garvarentz

An Interview with Georges Garvarentz by Philippe Loranchet

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.11 / No.44 / 1992

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

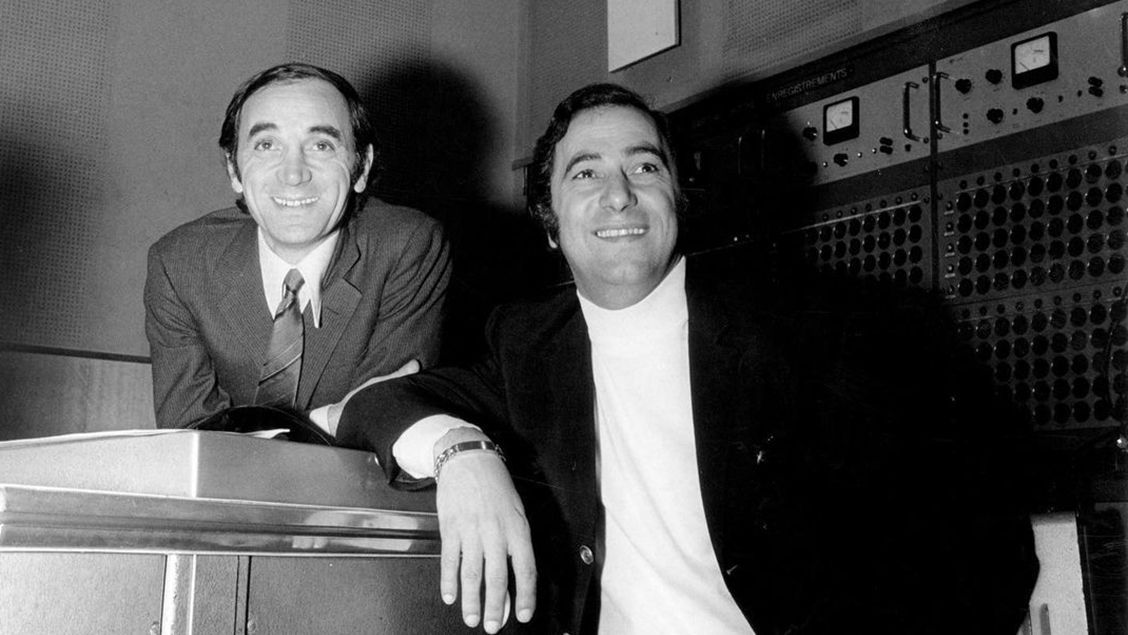

Georges Garvarentz is perhaps one of the least talked about of the great French film composers. Paradoxically, however, he is the man who has had the most success in the top 50, with famous songs such as “Retiens la nuit” and “Pour Toi Arménie”. Of the same generation as Michel Legrand and Georges Delerue, he has composed the music for hundreds of films since the 60s. He moved to the USA in the 70s, where he pursued an international career, returning regularly to France. His frequent travels and workaholism unfortunately led to a heart attack, from which he is slowly recovering. He was kind enough to answer Soundtrack's questions, and we take this opportunity to thank him once again and wish him a speedy recovery. The interview begins when the cassette is changed in the recorder. The cassette that came out of the machine was Borodin's Symphony no. 1.

Aren't 19th-century Russian composers the precursors of symphonic film music?

Absolutely, because they were composers of ballet and spectacle. The Korsakovs and Tchaikovskys needed to compose for the stage, for dance, which is like cinema: there's an image. There's no doubt that these musicians influenced composers... especially American ones. You know, we shouldn't be ashamed to say that we've been chasing Americans for half a century; we have to admit that they know how to make films. When Mr. Truffaut came back from shooting Steven Spielberg's CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, he said with modesty: “Finally, I've seen how films are made, I feel like I've never made a film”. You'd have to be as generous as Truffaut to say that. Over there, nothing is left to chance. Here, very often, the subject is badly written, the dialogues are not finished... There was a time when we knew how to make cinema in France, then came the time when we had to make films with 1.5 million Francs, we called it the new wave.

Did film music suffer as a result?

Of course it has! Because when the director is unsure of his work, he asks the composer to take a back seat. So as not to “eat up the images”, as they say. The writing of the film has to be as good as the music. At that point, there's no longer any struggle, there's only complicity.

What good French films come to mind?

At the moment, there are Jean-Jacques Annaud's films, among others, and all those films with Gabin.

How well did you know this period?

Yes, I did the music for almost all Denys de La Patellière's films, starting with UN TAXI POUR TOBROUK.

Your first film score?

Yes, and at first I didn't want to do it because it seemed so complicated. I'd read the script by chance and thought that a Handel hymn would be perfect to turn into a military march. The suggestion was made to the film's composer, who didn't understand, so the director (Denys de La Patellière) asked me to start work, and little by little what I was doing was used, so I signed the music. At the time, there were maybe a million electrophones and we sold a million and a half records! I signed a 3-year contract with the producer and off we went.

Are you classically trained?

Yes, my father was a musician, but initially it was my sister who was predestined to become a professional musician. She spent eight hours a day at the piano, so I was given a violin, which I later used to write for strings.

For which film did you first use a full orchestra?

For MARCO THE MAGNIFICENT (1965) with Anthony Quinn.

Was that your first epic score?

Yes, even more than epic, since I got the Vatican medal for it, let's say “epic christiano”! (laughs)

What was your source of inspiration?

At the time, I listened a lot to the classics: Bartók, Prokofiev, Stravinsky. I hope I've done something completely different.

Did you use atonal harmonics?

Atonal, yes, but not like Schoenberg. I don't do mathematics in music, which basically says that two identical notes must be separated by at least twelve other notes. I'm not a dodecaphonist at all.

Do you compose a theme for each character?

That's a good question, because that's the classic school of film music, but you have to be careful not to overwhelm the audience. Film music is above all symphonic writing. The greats of film music: Steiner, Waxman are German symphonists who left Germany because of the arrival of Hitler (in fact, Steiner was Austrian and left during WW1 - LVDV). They dreamed of composing symphonies and ballet music, but in order to eat, they had to put their musical knowledge and their formidable desire to write at the service of what was there: that is, films. They literally went wild. When Miklos Rozsa worked on BEN-HUR, he first composed a complete symphonic work as soon as he knew the story. That's how lazy he was! Then, when he saw the images and had to time the pieces, he sort of stole from himself, drawing from his symphony the themes he'd already composed. In fact, he recently recorded this symphony with the New York orchestra.

Do you know Miklos Rosza?

Miklos Rozsa gives lectures at universities to teach musicians about the relationship between music and images. I met people like Jerry Goldsmith and John Williams there, after he composed E.T.! Over there, you learn from experience. Let's take an example. In a film, two sequences follow one another; the first highlights the music, the second is very strong from a dramatic point of view. The composer needs to know how to remove the music from the first sequence to better reinforce its effect on the second. Keeping the music on both sequences would take the breath away from the second. These are little things that only experience can teach you.

Are you attached to a particular director?

No, not really, but I understand that you can be, like Williams / Spielberg or Lai / Lelouch, it's a question of chemistry.

What do you think of composers who give concerts?

It's wonderful, I gave one myself for TRIUMPHS OF A MAN CALLED HORSE. Music is perceived differently. All at once, everyone can imagine images. I myself have had chills at Goldsmith concerts and, without false modesty, I'm not ashamed to say that I get chills listening to my music!

Speaking of thrills, I personally got some when I heard your music for the Franco-Romanian TV series GUILLAUME LE CONQUÉRANT.

Yes, it was pretty good. In fact, the credits were played in Bayreuth alongside Wagner. It made quite an impression on me. But this music is Miklos Rozsa's influence, and I kept thinking, “How would he have composed this sequence?”

Do you use the synthesizer?

Yes, I have, but I find it a bit easy. When you've got the rhythm, everything sounds good.

What do you think of Jerry Goldsmith's use of it?

Goldsmith uses it to create new sounds. But given enough time, he's one of the very best. He was a pupil of Lionel Newman, who was never a great composer, because he was a bit crushed by his brother Alfred, but he was a very good teacher.

He also orchestrated music for Goldsmith.

In fact, in the United States, it's quite common. There's also Arthur Morton, an orchestrator who works for both Goldsmith and Williams. It's worth noting that these composers keep a very close eye on orchestration, as they are also capable of orchestrating. It's the same for me. If an arranger changes a note or a harmony, I'll kill him on the recording! In the United States, there are orchestrators' offices! At Paramount, there are doors marked "love scenes", "battle scenes", there are specialists. You put the pig in at the entrance, the sausage is ready at the exit! Goldsmith and Williams, given the time they have available, are obliged to entrust part of the work to an orchestrator; sometimes, they take on a particular orchestrator for a special scene. There's also the time factor for a symphonic score, sometimes only a month is given. The arm's speed of writing has its limits.

How much time do you ask for?

I ask for six weeks, or else I write like Delerue. That's not a pejorative at all, but he could get away with it because he made very fluid music for strings. There are four lines to write. Or make notes and pieces last, moods.

Did you work under strict time constraints?

Yes, for the series CHAMPAGNE CHARLIE, about the life of Charles Heidseck, I had in principle 10 weeks to compose 4 hours of music. Because of a delay in editing, I had to do it in 4 weeks. At the time, all the good orchestrators in Paris came to see me, and while one went out, the other came in, but I didn't sleep because he had to leave with a written score. I worked 22 hours a day. We got through it, but we were dead!

Don't you think these time and money constraints are becoming more and more pressing?

That's true, but you also have to know how to say no. Generally speaking, I get 80% of what I ask for in terms of time and salary. Nowadays, there are young composers who send a score to a producer without having seen the film or even read the script, simply on the rumor of a project, saying "this is my theme for the film". From then on, they're prepared to do anything to get the job. They're unaware, but I don't blame them, it's not their fault. There are producers in France, and you wonder if they've read the script. You'd think they were making films so they could have lunch at Fouquet's or go on vacation to St. Tropez.

Is there a difference with American films?

It's so different that in the States there's a budget for the music right from the start. On average, they plan between 250,000 and 300,000 dollars. In France, you'd have to do the same music for ten times less! It's not possible, even if you go and record in Italy or Hungary. But I think that French producers don't want to have intrusive music. There are exceptions, but the director, especially if it's his first or second film, is afraid that his baby will be taken away from him. I've often heard the phrase: “Georges, you can't do that to me, you're eating up my images”, and how can you eat up images? If the images are up to scratch, there's nothing to worry about. The musician can't contribute anything. In SPELLBOUND, it's the music that makes it clear that there's poison in the milk. The scene without music would be meaningless.

Are there any directors who think they know something about film music and in fact know nothing?

There are a lot of them. That's the trouble with cinema. They're the ones who say to me: “No, don't do that to me, Georges! It was so pretty what you played for me at home on the piano, you can't do the same thing to me again!” So you bust your ass writing for 90 musicians and in the end, I find myself in the recording studio playing the piano alone, and what's more, I don't play very well and everyone thinks it's great. You've got to do it! (laughs). There are a lot of them. They'll recognize each other!

Conversely, have any of them impressed you?

Yes, De la Patellière, Terence Young, people like that. For example, on GUILLAUME LE CONQUÉRANT, they let me do exactly what I wanted. I'm not saying that's why it's good, but it's close (laughs).

Did you have any problems using temp-tracks?

It's when the director chooses a temporary score. I've just done a musical in the USA: STAR FOR TWO with Anthony Quinn and Laureen Bacall. The editor had the good idea of putting Puccini's music in it, and the director got used to it. So you know, to dethrone Puccini, you have to wake up early. That's why I woke up early, by the way (laughs). I did something that the director really liked, but I was in agony because I also liked the music.

How many scripts do you read a year?

About twenty. Half of them I'm not interested in. Of the other half, half don't get made because the financing doesn't work out.

How do you make your selection?

I have to believe in the project and the subject. When I read the script, I can tell if it's written by an intelligent person or not. Sometimes I find stupid or pseudo-intellectual things in the dialogue. It bores me! For me, cinema is entertainment. I want to be able to tremble when I watch films. When I see IVANHOE or TARZAN again, I love it. If producers were to remake these films, they'd sell a lot of tickets. These are immortal subjects.

Who decides where there should be music in a film?

In the United States, it's the composer alone. You have to deal directly with the producer. And then, if the music isn't right, he'll tell you “it's not right, it doesn't suit this film”, but he's not angry. He can call on you again. In France, everyone's immediately pissed off. If it doesn't work, it's because you don't understand anything, because you're no good.

Have you ever composed music that was never used?

Never! But in the United States, it's common and not a disgrace. I arrived over there in 1976 to make a film for Paramount. It was a MANNIX spin-off. Bill Stenson, the big boss of music at the studio, when it came to signing the contract, said to me “Georges, you're doing your best, but if it doesn't work out, don't worry, we'll get someone else to do the music!” As a Frenchman, I was terrified to hear that; it was only later that I realized it was commonplace.

What do you think of soundtrack albums, which end up containing more songs than orchestral music?

I'm facing this problem right now with the music I did for WHISPER WHITE, a film set in New York. I'm in discussions with the producer, who would like to release the record with the songs and fill the little space left with the film's music.

Do you conduct the orchestra yourself?

No, I'd rather be in the booth during the recordings (laughs). The one time I tried it, I recorded a minute and a half in a day, instead of ten with another conductor!

Do you think there's still room for symphonic film music in France?

Yes, we'll come back to it once we've had enough of these little gumshoe themes and synthesizers.

There's no shortage of orchestras in France…

No, but you have to write something for the orchestra, but that's bound to happen, new composers will emerge.

Does orchestral music cost more than synthesizer music?

No, it doesn't. No. Considering the hours you have to spend in professional studios at the price it costs. Or maybe some people do it in their bathroom. Then it's different.

Is there any music, by Goldsmith for example, that you particularly like?

No... Because I love Goldsmith! I'm an unconditional fan! Everything he does, even if it's bad, is good. Whatever music he does, he's got his fingerprints on it.

What kind of films do you prefer to compose music for?

Adventure or epic films. I'm not much for comedy. I did a lot of comedies with Poiret and Serrault in 1965, but maybe I just got fed up with them. Now I'd like it to be big!