An Interview with Maurice Jarre

An Interview with Maurice Jarre by Daniel Mangodt

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.12 / No.45 / 1993

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

I've been a fan of Maurice Jarre's music all my life. In 1984 I saw his ballet Notre-Dame de Paris in a choreography by Roland Petit and I attended two of his concerts at the Barbican: the first in 1985, with David Lean present and the second in 1991 in honor of the director. Each time I was able to attend the rehearsals and in spite of a maddening schedule, Maurice Jarre always had time for a few words. During these concerts Jarre proved to be an admirable entertainer with the short speeches he made.

Late last year he was invited to Düsseldorf by Udo Heimansberg (also a Jarre fan for many years) for the premiere of the composer's new film AGAGUK (SHADOW OF THE WOLF) which was held at Udo's cinema November 12. There was a press conference November 11 and Maurice once more turned out to be the perfect causeur. In an inimitable way, and not without some irony, he talked of the many experiences he has had in a career that spans more than 30 years in film music.

The following is a brief résumé of many of the interesting comments of the press conference, followed by the interview proper. There are two ways to compose music for a film: there is a good way and there is a bad way. Too often only the bad way is possible: not enough time, last minute changes, problems with the director, the producer, and so on… A good way is possible, but then you must work with people like Peter Weir, Volker Schlöndorff, David Lean. Georges Franju...

There are three kinds of directors: the first kind are the musically cultivated ones like Zeffirelli, Weir, Visconti, Schlöndorff. The second kind are those who actually don’t know anything about music, but who express their ideas with feelings, with images. David Lean is a case in point. When Lean was explaining the beach scene in RYAN’S DAUGHTER to Maurice, he said. “It's a beautiful scene, they are on the beach, it's beautiful weather, but there is something wrong. The music should come from here” and Maurice stood up and pointed to his groin. The third kind are those who think they know everything about music, but they don't and they spoil everything by giving the wrong directions. Jarre is so gentlemanlike that he didn't give any names, too bad.

Jarre left France because the French were driving him crazy. Not Franju, of course. Jarre still thinks very highly of the late Franju - and with good reason. After all he owes a lot to Franju and to Jean Vilar, the director of the TNP (Theatre National Populaire). He clearly admits that these were the best years of his life.

Jarre commented that he won't be doing NOSTROMO, if it is eventually made (there are plans to make the film after all), because he would consider it a betrayal to David Lean and he certainly won't be doing GHOST II, because he dislikes sequels.

Jarre loves to travel. Sometimes he visits locations, for instance for THE MESSAGE and for THE YEAR OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY. He was forced to use electronics for this film, because of some problems with the musicians who refused to work for the film company. He composed the music for THE MOSQUITO COAST before shooting started and Peter Weir tried to edit the film to the music. In fact Jarre had to write a completely new score to adjust to the film.

He told some wonderful stories about Italy, Japan, India (he had to write the Indian music in a special notation, because the musicians couldn't read the music), David Lean, Hitchcock, etc. Maybe one day he'll decide to write an autobiography. He has so many anecdotes to tell.

After the showing of AGAGUK, it was signing time for the fans and Jarre didn't disappoint them. When he was asked to sign Silva Records's release of LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, it became clear he's still bearing a grudge about this re-recording. “This CD belongs in the dustbin”, he stated. Maybe one day he'll tell us what went wrong.

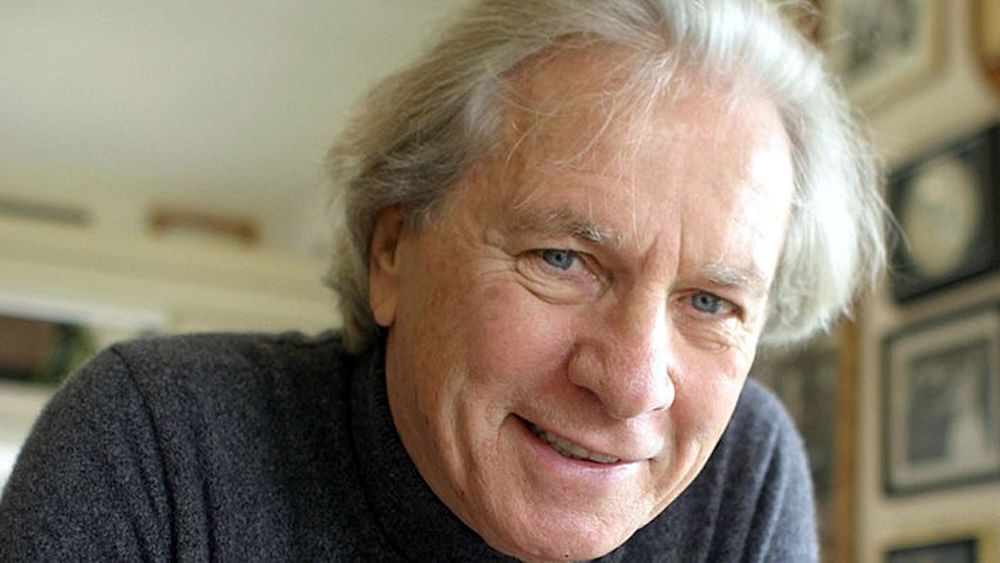

At the age of 68 Maurice is still a handsome man (as a matter of fact there were many female fans present, which shouldn't surprise us). In 1952 Elisabeth Barbier wrote about him: “Ce garçon aux yeux bleus, qui a l'air d'un adolescent angélique, est à son aise dans le surnaturel, voire l'inquiétant. Quoi d'étonnant? Il est en réalité, un possédé. De l'espèce tranquille, mais un possédé bel et bien.” (Présences Contemporaines: Musique Française / Jean Roy. - Paris : Nouvelles Editions Debresse, 1962, p. 444) (Freely translated, it means, “This young man with blue eyes, with the face of an angelic adolescent, feels at ease with the supernatural, even the disquieting. What's so amazing about it? Actually he is possessed. In a mild way, but possessed anyway”).

Could you tell us something about your last film AGAGUK. What's it about?

It's the second film I've done for Jacques Dorfmann (the first was LE PALANQUIN DES LARMES). He is a young director who is still learning. It’s more out of friendship I wrote this music for him. It’s an interesting picture. We know very little about the Inuit society. The eskimos are a really strange people, their way of living is strange, mainly because they have to fight the cold. They have interesting customs. It's a very primitive society.

What interested me was the challenge. There is basically no Inuit music. They have drums - not a variety of drums - but basically one drum, a kind of moon-shaped drum and they don't have a kind of chant, they have some mumbling (Jarre imitates this). There are only 2 or 3 notes in this kind of primitive chant. When there is an ethnic element involved I always try to use ethnic sounds. In this case I couldn't do too much, because there was not much variety. So basically I used a normal symphonic orchestra, because it's a big space and I used one Inuit female voice which I doubled and tripled and quadrupled to make a kind of little choir. When the wolf appears - the wolf in this case is not really one animal, it's more than that, it's a symbolic creature: it represents the soul of the shaman - I try to identify him musically and I gave this kind of choir a little bit of electronic background.

So finally there are two different kinds of music: the big orchestra and this strange combination of voice and electronics. Later on when we don't see the wolf, we play its music without seeing the animal, the audience knows the wolf is around. Again it's not the animal, it's threatening.

As in JAWS. Do you also reflect the savagery of that society in your music?

I tried to do it. There are two different orchestrations. First one normal classical orchestra with strings, woodwinds, etc., and the second is an orchestra without any strings at all, just basses, including 8 horns and 8 Wagnerian tubas, which give this score a kind of savagery, plus percussion and a baritone saxophone to emphasize the basis of the thing, and also to give a little touch of the sinister: this big icy frozen space gives you a frightening feeling. We realise that these people live there all year long and they have no chance to survive without weapons to get their food. It's worse than in Africa. I suppose dying from hunger and cold is even worse.

About your use of electronic music... In an interview about 20 years ago you were asked about the use of electronic music and you were not very enthusiastic about it. Since then you have written about 15 scores with electronic music. Why this sudden about-face?

First of all, when we talk about 15 or 20 years ago the use of synthesizers was very depressing, because film producers thought when they had one synthesizer and one player they could double or triple the instrument and try to make a big sound and replace an orchestra, which is ridiculous. That's why I was totally against this electronic business at that time.

Especially on television, you have one synthesizer player doing exactly what I was afraid of: just playing track after track after track and sounding awful, just trying to imitate strings. No synthesizer - even the most sophisticated one - can imitate the sound of violins or the viola. The celli and basses can be played rather close to the sound of real celli and basses. With electronics you can never replace an orchestra, that's why I was so much against it at the time.

With technology evolving and the evolution of digital recording we started to create a new tool for the composers. Instead of thinking about imitating orchestral instruments to save money or trying to put more tracks above the other ones, I began to realize we could do something totally different and that's why I think - and I'm saying this without any pretensions - the score for WITNESS showed the way for a different attitude towards electronics. From a financial point of view scoring WITNESS (with electronics - DM) must have cost much more than if I had done the same number of sessions with a normal 80 piece orchestra.

You had very good synthesizer players, like Michael Boddicker…

Exactly. People like Ralph Grierson, Rick Marvin, Michael Fisher, Judd Miller. Besides, I didn’t work with one synthesizer, I worked with the electronic musicians like a chamber music type of orchestra. So each player had five or ten different synthesizers and with six or seven instrumentalists you have an unbelievable choice of sound. With the electronic genius of the E.V.I. (Electronic Valve Instrument), which was invented by Nyle Steiner (it’s a kind of woodwind electronic instrument) you can create a human sound instead of staying on the keyboard synthesizer and using this as a complement to the normal synthesizer it gives another dimension. I also try to use some ethnic element, like for instance the Japanese Shakuhuchi (bamboo flute), or something like that. So the music I wrote for films like FATAL ATTRACTION, NO WAY OUT, MOSQUITO COAST and JACOB'S LADDER uses electronics in a totally different way.

That's why I changed my opinion. And it's also very interesting to mix some electronics with orchestra - I was not the first composer to do that, Jerry Goldsmith and James Horner did it first. But WITNESS was definitely something a little bit new as far as an electronic approach was concerned.

During this time I heard someone from the musician’s union saying: Oh, my God, Maurice Jarre is doing something very dangerous because now we are going to have electronics replace a live orchestra. That was totally wrong. As I told you, scoring WITNESS cost much more money than with a live orchestra. Besides, you can't use electronics the way you can use a big acoustic orchestra and vice versa. They both have their reason for existence.

I think the “Building the Barn” scene in WITNESS is a copybook example of beautiful scoring, yet people are asking why you didn't use a normal acoustic orchestra?

Well, first of all there are some sounds I couldn't get from a normal orchestra. That's one thing. Then we come back to the basic concept of the music for WITNESS. When I was asked to do WITNESS, I started to study the music of the Amish society, and I discovered that just any kind of instrument in this society was considered to be more or less the weapon of the devil. Consequently I thought if I was going to put any kind of acoustic instrument in the score, it would not be right, because the Amish society does not allow musical instruments, so I choose to use electronics.

The second reason is the Amish have a different, clean way of life. So clean that's it's almost close to coldness and to express this coldness it was more interesting not to use vibrato instruments like strings and even woodwinds. In a way the electronic quality of the synthesizer, the E.V.I. and electronic percussion create a little coldness and these are the two reasons I didn't want to do it with a conventional classical orchestra. But for the concert performances I made a transcription for “Building the Barn” for orchestra and it’s interesting to hear the sound. If I had to redo WITNESS without any financial limitations, I'd exactly have done the same thing.

I still think it sounds beautiful in electronics, it really gives you the kind of atmosphere it needs. When I heard it in concert, it sounded a bit Coplandesque to me.

It's a very classical form of music, it’s a passacaglia. It's a nice compliment you gave me. Coplandesque means more classical things. That's why Peter Weir and I chose to have this special feeling, this special sound.

Did Peter Weir use a temp track for this scene?

Yes. Peter Weir used a piece he loved: a canon by Pachelbel. He edited the film to the music. So I was confronted with this temp track, it worked so well in the film. When we were ‘spotting' the film. Peter said, “In this case I put in music I love so much, I think I'm going to keep it. You may try to score this scene if you want to do something, but I think I will keep the music”. It was a big challenge for me. I came back to my office and I started thinking about this piece and I studied how he had edited it to the music. I made some kind of map of the dynamics of the cut and I started to write the theme I wrote for the film and started to adjust my music to this map, completely technically.

I hadn't completely finished the music, I was playing with the musicians and Peter arrived a little bit earlier than expected and he asked “What is that?” I said it was my suggested piece of music for the barn scene. He said: “That's great, that’s fabulous!” and he started to be very excited and he never mentioned the Pachelbel canon again.

So you won from Pachelbel! You also won from Mozart…

I was lucky this time that Mozart wasn't eligible. AMADEUS was filmed at the same time as PASSAGE TO INDIA.

Sometimes you combine electronic music with a solo instrument, as for instance in GABY, A TRUE STORY, which is a marvellous film.

I agree with you completely; a small, but very good movie. I used a cello in combination with electronics. That's also a thing I like to explore: the mixture of a solo acoustic or ethnic instrument with an orchestra or with electronics. In GABY it was interesting to have this solo because there is no way to confuse the cello solo with any kind of electronic imitation of a cello, plus a group of synthesizers.

The cello is a warm instrument.

Absolutely, but not sentimental. A good film should never be sentimental. At times very sensitive or touching, but sentimentality is a thing I always try to avoid in any kind of music.

You work with people like Christopher Palmer, Michel Mention, Richard Bowden. How is your relationship with your collaborators?

For me, orchestration is a part of the work of the composer. When you have a long score, and you don't have too many weeks to complete the assignment, you need someone to help you, but help is very dangerous, because for me orchestration is the color of the score and if you don't have somebody who does exactly what you want, you've got problems.

Sometimes the orchestration is basically a copy of a smaller map you have. Fused to have specific instructions on what you call a sketch - in fact it's a very sophisticated sketch - and I'm very careful about using percussion, or about using a new electronic instrument. Even Christopher Palmer, who is one of the most intelligent and most musically cultured people I know - sometimes he doesn’t know what I mean by E.V.I. or which sound I want to introduce electronically. If I don't put the maximum of information on my sketch, he will probably make a wrong decision, if it's not the right combination with the electronics I'm using.

When you find a collaborator like Christopher, it’s very good, but I'm always open to different people, because you're never married. It's the same with a director, I don’t want to do all the films of a particular director. But of all the people I worked with, Christopher is probably the best.

You like percussion. You started as a percussionist with Pierre Boulez in the late forties. I remember that the main title for DIE BLECHTROMMEL consists only of percussion and even so at one particular moment you hear a theme coming out of the percussion.

Again, DIE BLECHTROMMEL means exactly what it means. You have a tin drum which has a metal sound. I try to bring the audience in the right mood from the beginning with all these sounds by different drums. The main character is a boy who doesn't want to grow up. I used a different kind of percussion instrument, called a flexatone, which does ‘djinn’, some kind of a little bell, it makes people think of children but it also sounds a little strange, you hear there's something wrong. It's not a nice nursery rhyme.

I believe you used the same instrument for Michael's Theme in RYAN'S DAUGHTER?

Not exactly the same instrument. That was a different combination, even weirder. In DIE BLECHTROMMEL, there was only a little touch of that. He's not the same character as Michael. He's still a child, with a little purity in a way. That's why he such a fascinating character. The creature of Michael on the other hand is very disturbed, in almost a demented way. I used an even stranger combination if I remember well: there was a cymbalon, a salterio, a zither, a kamanche (a kind of oriental, single string violin). It was an interesting combination to orchestrate for. You see, when you have a problem like that, you can’t give it to an orchestrator and tell him. “Try to do something with it”. You have to write exactly, for each instrument, what you want to obtain.

That's one of the reasons why I like your music: you are always looking for the exotic, the ethnic.

And I like that. Unfortunately you sometimes have big problems trying to find a player who can play these instruments well enough, and also trying to find someone who can read the music. In many cases you have to practically spend hours rehearsing with these people. Now it's fantastic, you have a sampling and you take one note of a strange instrument like, say, a Gambian instrument - for instance the kora - which is a very difficult instrument to play and it's very difficult to find a player - and you sample that and you play it on the keyboard like the most virtuoso kora player!

The problem was even worse when I was doing ZHIVAGO. I did not want to have 2 or 3 balalaikas, but an orchestra of 25 people. I was lucky enough to find these 25 people in Los Angeles, but they couldn't read music. So I had to teach them the 16 bars of “Lara's Theme” and when we recorded the music, I had a symphonic orchestra in front of me and my balalaika players on my right, I had to mime with my mouth just to show them which kind of rhythm they should play. It worked well, but it was much more difficult than with people who could read music.

You like to use several instruments at the same time, for instance you used a dozen harps in RYAN'S DAUGHTER…

Eight (on the record sleeve it says 9, so we were both wrong - DM.)

Twelve pianos in PARIS-BRÛLE-T-IL to illustrate the Germans marching through Paris…

The reason why they say Maurice is becoming really crazy now, he wants to use 12 pianos.

You mean, you were being criticized at the time for using so many pianos?

Sure. There is a reason why I used 12 pianos and not 8 or 6. Unfortunately we didn't have a really good engineer and the effect I wanted was not realised completely. When we rehearsed the beginning of IS PARIS BURNING?, the idea was not to use the cliché of percussion illustrating the marching goose steps into Paris (Maurice imitates the Germans marching), but instead of that starting with one piano, just playing a cluster on the lowest part of the piano and add two pianos, and then three... to give the feeling we were surrounded. We felt the Germans marching into Paris with this kind of sound and when we played that in the recording studio, the director and the producer were absolutely astonished by the strength of this music at the beginning. But we don't hear that very clearly on the record or on the soundtrack, because unfortunately at that time il was not a digital sound and because there was a large orchestra, they didn't have enough microphones to put on the pianos. Can you believe that? That was ridiculous, and again the engineer was not a first-class engineer. The effect was no right.

Sometimes you use a large orchestra sometimes one instrument only. There is a beautiful scene in DIE BLECHTROMMEL, ‘La Poste Polonaise’ where you imitate a Chopinesque waltz, which starts and then stops, starts again and stops again about 5 or 6 times. It is an example of counterpoint scoring.

When we talked about this sequence with Schlöndorff - who by the way is one of the most musically cultured directors I have ever worked with, together with Peter Weir and Visconti - he told me it's a really dramatic and important sequence for me, maybe we ought to add some military drums to emphasize the strength of the military, the tanks, making the scene stronger by adding some more percussion. I said let me think it over. I was fascinated by this scene and I said I felt we could do better by just adding percussion.

And one day I said to Schlöndorff, “Look, maybe it would be interesting to do the contrary and play the music against the scene: we see a very dramatic scene with a lot of explosions. Polish Post means Poland. What means Poland musically to the audience? They immediately identify it with Chopin, a romantic Chopin waltz. Let's say I play the piano just with one hand, a kind of little waltz à la Chopin (Maurice hums the waltz) with silence”, and suddenly Volker looked at me and said, “That's great, Maurice. You know what I’m going to do: I'm going to stop practically all the sound effects and make them sound as if we hear them in the snow, something very muted, very dampened.” So in this scene we see some horrible things with ... (Maurice hums the music again) with ‘chew’ instead of ‘bang, pang’. In this case we have a dramatic scene with music totally scored against the film. That's an example of how I like to use music.

Unfortunately again, critics sometimes accuse the composer when they don't like the music in a particular scene. It's not the fault of the composer, it's the fault of the director who forces the composer. You are hired to execute more or less the feelings of the director. You can argue, but at one point you have to do what he says, what he asks. Also, the quantity of the music may be a problem. Always when I see a film I want to have much less music, because music is supposed to say something. If you see a scene and it's very well done, why put more sugar on the cake in this case? It's very aggravating. I have had lots of experiences with directors who are a little bit insecure, they don't trust some scenes (to work on their own) and they think the music will give more information to the audience. If the music only illustrates the film, we just don't need the music.

Personally I think there is a little bit too much music in RYAN'S DAUGHTER…

That was part of the criticism, but I don't think so. You see, the film arrived at the wrong time. There was a lot of snobbery. Any film made for less than $200,000 was obviously a very good film, even with a lot of bad music, very badly recorded.

With RYAN'S DAUGHTER we tried something the critics didn't get and the film was attacked, even slashed. I still think it is one of the best films ever made. Now it's going everywhere. Now they love the movie. When A PASSAGE TO INDIA was released, I was stupefied to read in Time magazine (by a critic who panned RYAN'S DAUGHTER 15 years ago): “Oh my God, David Lean did this beautiful film, A PASSAGE TO INDIA, but remember RYAN’S DAUGHTER and DR. ZHIVAGO and even LAWRENCE OF ARABIA.” They called it the sand opera at the time.

Sometimes you work for fairly unknown directors, for instance William Richert who did WINTER KILLS and THE AMERICAN SUCCESS COMPANY…

I'm not being sarcastic, but you see, the fact that they are fairly unknown is probably because they deserve to be. In the case of Bill Richert it was a very difficult subject (WINTER KILLS) and unfortunately in Hollywood, if a film flops and you do another film with the same result, that's it. You are then totally ignored. He hasn’t done anything since. I think it's wrong, because this film about the Kennedy business was a very interesting movie with John Huston playing a marvellous villain.

I have another example, a very interesting film called JACOB'S LADDER. No success at all. The film was a little bit too complicated for modern audiences. They want to understand everything very fast and that's the reason why we have less and less intelligent films, because people want to go and see films like BATMAN, or LETHAL WEAPON Numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8! It's very sad. I don’t criticize pictures like these, but you shouldn't make several sequels when you have had a successful movie.

You have scored several westerns, I particularly like VILLA RIDES!

VILLA RIDES! was not a very good film. It was a good subject, but not really a good film and I'd love to do westerns. One of my favorites was THE PROFESSIONALS. Buzz Kulik was a nice man, but he was not really equipped to do a really good film.

There was something missing and your music couldn't save it completely. You also did EL CONDOR…

That was interesting again. Here it was not the fault of the director or the producer, but of the studio which went bankrupt and didn't distribute the film very well and didn't make any effort to promote the film.

MANDINGO?

That was really a mistake. Sometimes you read the script, you think it's going to be a good movie, you sign the contract and then you are confronted with a very bad picture.

(The interview had to be interrupted here because other journalists were waiting to take Daniel's place - if you can get an hour with a well-known composer like Maurice Jarre you can count yourself lucky - but we hope this conversation will be resumed at a later date. Special thanks to Udo Heimansberg for making the interview possible. LVDV)