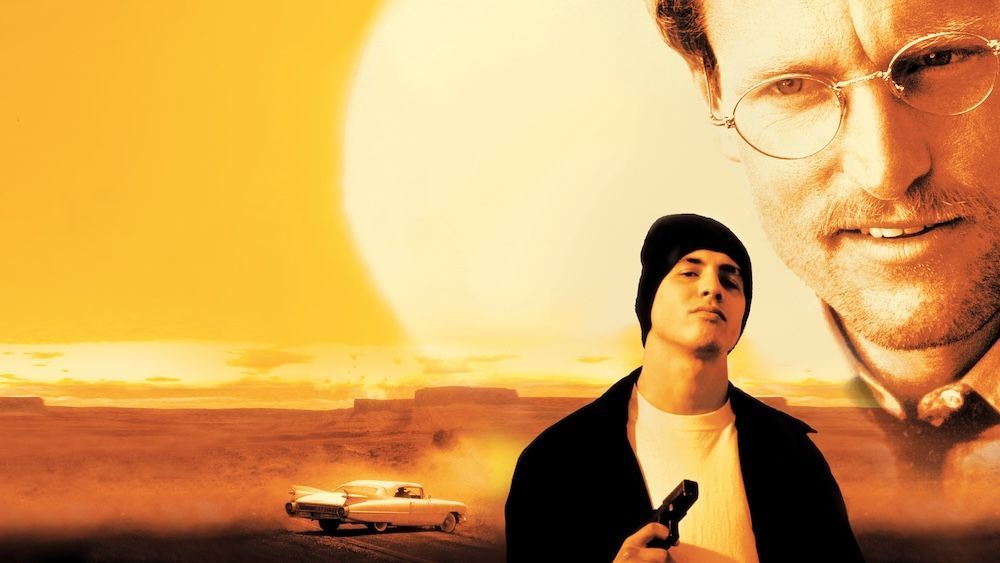

Maurice Jarre on Scoring The Sunchaser

An interview with Maurice Jarre by Daniel Mangodt

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.15 / No.60 / 1996

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

Maurice Jarre fans have every reason to be delighted: this Summer Jarre gave an open air concert in Berlin, a career achievement award dinner given by the Society for the Preservation of Film Music took place last October and his concert at the Royal Festival Hall in London a few days later (on October 16) attracted quite a crowd.

The highlights were a London premiere of a suite from THE TIN DRUM and 2 world premieres: a suite from THE YEAR OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY complete with gamelan, Ondes Martenot and EVI, and a Concerto for Electronic Valve Instrument, Strings and Percussion.

At the age of 72 Jarre seemed to be in top form, clearly enjoying himself during the sold-out performance and demonstrating once again his talents as a raconteur. This short interview took place at the Dorchester Hotel in London. Some of the questions and/or comments are by Trevor Willsmer, the editor of Movie Collector. Later that week Jarre went to Paris to attend a performance of his ballet Notre-Dame de Paris at the Bastille Opera, an event he wasn't even informed of by the people who organized the event…

THE SUNCHASER is your most recent score…

When Michael Cimino started the film, from the beginning he thought about me, but he had a lot of problems with the production. They told him Maurice Jarre wouldn't be available and he'd be too expensive anyway. But Cimino was persistent, he sent me the script and I liked it. It's an engrossing story, a movie with real characters, like in the seventies. This kind of film is making a come-back, like RYAN'S DAUGHTER, which was a flop when it had its release, but a few years ago when it was shown again people applauded. I saw the film in pretty bad conditions, and I didn't even see the ending at the time, because they were still editing the film. I liked the movie and it was very interesting from a musical point of view: there were big open spaces (kind of Americana) and a character confrontation between the Indian Blue and the doctor who is kidnapped by Blue. They live in 2 different worlds and in the end the doctor has to admit that there may be another way to cure people, not only the scientific way, which is kind of a modern theme.

What approach did you take?

When you see a film in its final cutting stages, if the film is good you really feel inspired. Good directors like Cimino, Lean or Weir know very well what they are expecting from the music. So you have to express your ideas and it's a kind of collaboration. I love to work very closely with the director. They say you are not free when you are writing music for films. That is not true. I still write the same kind of music I wrote a long time ago with different directors. You have to be able to go with the director's point of view, but still it is your music. THE SUNCHASER has a big orchestral score. After all these big movies like LAWRENCE and IS PARIS BURNING? it was very difficult for me to ask directors whether they'd allow me to write an electronic score or a score for small ensemble. They said “No. You are very good at writing those big scores.” Finally I was allowed to write an electronic score for THE YEAR OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY for Peter Weir and for other directors and recently my agent got a call from a producer who wanted me for his movie and he asked: “Can Maurice write an orchestral score?”

There is a piece by Copland from Appalachian Spring in THE SUNCHASER (it occurs when they are driving their car through a pack of horses).

Michael Cimino chose that because there was so little time. I had two weeks to write about 45 minutes, and I said I doubted I could write all the music. Cimino told me not to worry and he suggested to keep Copland's piece for this particular scene. And I was relieved.

Did he use that as a temp-track?

It was on the temp-track and it works very well. The only thing I did was to write an intro and an ending to Copland's piece so that it comes across as one piece.

Warner Bros. were a little bit wary about giving Cimino too much control over the film. Was that manifested when you were working?

Warner Bros. were very happy. The problem was with the publicity surrounding the film and with the Cannes Festival where the film was shown in competition. Everybody from the Cannes organisation loved the film and they wanted to give it “Le Prix du Jury”, but Francis Ford Coppola disliked Cimino and so the prize was given to another film.

What happened on THE RIVER WILD?

I worked with the director, Curtis Hanson, and producers Larry Turman and David Foster. They always came to the recording sessions and everybody was very happy. We mixed the music and everything was fine and we did the record and the people from RCA went to see the movie with the music and they liked it. Curtis Hanson had even written liner notes for the CD booklet. But the preview was disastrous and the head of the studio at Universal, Sidney Sheinberg, didn't like the movie. He ordered Hanson to change the music, who was really surprised, but Sheinberg was the boss. The next morning, they called Jerry Goldsmith. So, fine. I was paid. In the end Sheinberg wanted to change Goldmith’s music also, again because he didn't like the music. What qualifications does this guy have? Does he have a degree in music? He is a business man. He knew that the film was not really good and when he realized that, the only thing left to do was to change the music. David Lean told me once a composer can be a doctor. The only problem is when the patient is already dead. You cannot save the film.

Producers tend to regard the score as the last chance to save the film, like with THE SCARLET LETTER, which is a dreadful film. You've been in the line of fire a few times, especially lately…

I think it's because directors have less power than before. They couldn't do that to Hitchcock or David Lean.

One of the reasons is of course that films are so expensive nowadays and film scores have become so much more expensive to perform…

I'm not so sure about that. They send a lot of composers to the East-European countries and it cost 10 times less, but lately they are charging more. I turned down several films because they wanted me to go to Hungary. I said “No”, because we have the best musicians in the United States and London is fantastic also. The orchestras are wonderful here, because they play together every day. But even in the States a pick-up orchestra is very good. France is out, because the French are not really professional. The studios are not so good in Eastern Europe; they have to bring in recording engineers and so on. I don't think music costs more. The thing is, it costs more if you have 3 different scores! I even heard that Demi Moore had a lot of say about the music for THE SCARLET LETTER.

The rumor is actually that Elmer sent her a thank you note for rejecting the score, saying that now he could use it on a better film.

An assistant in L.A. told me that Elmer's music was wonderful.

The same thing happened on WHITE SQUALL…

That was worse. I was supposed to do BLACK RAIN for Ridley Scott, but I didn't do the film, I don't remember why. When he asked me to score WHITE SQUALL, I was curious why he asked me. He had used music from WITNESS and DEAD POET'S SOCIETY as temp-track. He wanted me to write music in the same mood as for those two films. It was partly electronics and there was a little choir and an orchestra. We decided to start recording the electronics first. So we did one session with electronics and he came in late and I told him what I was doing, and he asked me to continue. Before the second session started, the producer told me Ridley didn’t want me to continue with the music. He had changed his mind. He didn't want to have the mood of DEAD POETS. He would have liked to have more time to cut the film.

Everything was ready, all the musicians were booked, the choir was booked and I said: “Let me at least record what I wrote, because no matter what, you are going to have to pay these people and we have 3 full days of recording ahead.” The producer had no idea what it is like to work with musicians. You have to pay the musicians and the recording studio. But they decided to stop after just one session. I couldn’t believe it. I called Ridley and he told me he had made a mistake to have the same mood as DEAD POETS. The real problem was that they realized the film was bad and Ridley wanted to have some time to recut the film. Actually they wanted me to wait until February (this was in December of last year) and then write a second score for the same money. In the end they had to pay the full three days: an orchestra of 80 people for 2 days, five men for the electronics plus the choir, plus the studio. They could at least have recorded the music.

You sued them.

Yes. I was paid in three installments. The first two payments were okay and they thought the third payment was a part of the deal. I had to sue Ridley Scott to get my money. Big movie moguls like Zanuck or Spiegel were careful with money. They cheated a little bit, but they knew what they were doing. But I signed a contract. This year 7 or 8 composers were fired from the film they were working on, people like Silvestri, Bernstein.

I heard that there will be no CD of THE SUNCHASER?

Maybe the re-use fees were too high or maybe there was a song they wanted to use. Probably that was too expensive. But I always mix for a possible CD.

In the fifties and early sixties you wrote a lot of “classical music”, e. g. the Mobiles pour Violon et Orchestre and the Cantates pour une Démente. They were never recorded.

We have a project with Milan to record some of those pieces. You heard this piece yesterday. I wrote the Mobiles for a violinist called Devy Erlih. When you write a piece like that with a lot of freedom for the soloist it is very difficult for the orchestra and you cannot have too many rehearsals, because it costs too much money, especially now.

For the Cantates you used a special way of notation.

How did you know that?

I read it somewhere (I actually read it in the late Nicolas Slonimsky's “Music Since 1900” where he wrote that the score was notated both acoustically and pictorially as a partition-tableau.)

It was based on letters from women inmates at an asylum for the insane and I based the music on a painting. I have always been interested in painting. Maybe I was influenced by Franju's LA TETE CONTRE LES MURS aka THE KEEPERS). And I was interested what a mad woman would paint, I used a canvas, and after that I put some lines horizontally and vertically and I designed it like a score; I had to reconstruct the music with what I did with the painting, the colors represent notes. It was after all a kind of intellectual exercise.

When I listened to the concerto for EVI yesterday, it took me back to your early career.

I loved to do that. For this concerto I worked with Nyle Steiner (I worked with him since WITNESS), the inventor of the EVI. He is a genius and I wanted to introduce him to an audience with this totally new instrument. The score is a classical one, very tonal. This instrument can imitate almost every instrument except the violins. It has an incredible scope of sound. I tried to manage with each sound a combination of instruments, and instruments from different families. For instance one sound was a combination of harpsichord, flute, bongos, harp and vibraphone. The sound is a mixture of that. In other words it creates a totally new sound, but it is still musical. It can imitate an electric saw or a drill or bells or a kind of rap music and besides that you have something very melodic.

What are your future projects?

Maybe to write more music, not necessarily for films. I did this

Concerto for EVI, just seventeen minutes, in two months and I really enjoyed it. It's wonderful to write and not to have to work for these kind of jerks. I will probably do the next Peter Weir movie. He is working on a very interesting script, THE TRUMAN SHOW. It's almost science fiction. You know, at my age and at this point in my career, I don't care. I have my house, I have 3 dogs and I have a wife, not necessarily in that order (laughs). It's wonderful. I'm very happy.