Zdeněk Liška : Revolution Behind the Silver Screen

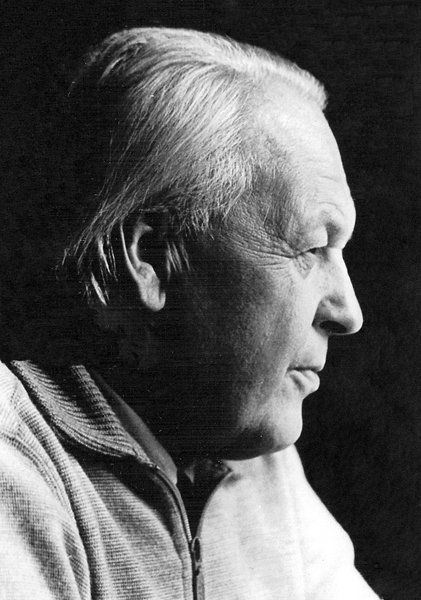

There is probably nothing we could call underground film music, but there is certainly an innovative scene for film soundtracks. The composer Zdeněk Liška (1922–1983) was an innovator of revolutionary parameters, but he lived at a time when Czechoslovak film music was not published separately. Today, the world is gradually discovering his name outside the frame of cinematography, on releases by British label Finders Keepers or the Polish brand Bolt Records.

And there is certainly a lot to discover. Liška pioneered film music in Central Europe, he composed the music to the Oscar-winning THE SHOP ON MAIN STREET (Obchod na korze, 1965), and also managed to convince film-maker and artist Jan Švankmajer that music can mix well with a surrealist imagination. He bound his life to cinematography and scored several hundred films – the crucial aspect, however, is quality, not quantity.

We are currently in a period of re-evaluation in regards to the 20th century. Forgotten stories re-emerge. Points of view change, and what was once marginal can meet what a later conception sees as valuable. For too long, film music was considered an “applied art” in Czechoslovakia, and the publishing politics of state-operated labels Supraphon and Panton (between 1948 and 1989) made no claims to it for neither documentary nor commercial purposes. The Soviet bloc states had centrally planned cinematography, freedom of speech was partial at best, and artists often had to cloud their opinions in metaphor.

Concurrently, however, there was a functional system of film production groups, and centralised production included not only high quality sound studios, but also the possibility of using Fisyo – the Film Symphony Orchestra. Artists walked a narrow path: they had to try and find ways of using these excellent resources in their works without expressing too much loyalty to the powers that be and their ideology. Film music, graphic design for books, translations from foreign languages or work for children: all these fields became the home of artists that would at other times have expressed themselves through original work.

The freest time for Czechoslovak cinema was the 1960s. Films by authors connected to the new wave (and others) have timeless value. Zdeněk Liška made his strongest works in the 60s and 70s. His story, however, begins in the 1940s. Liška finished the Prague Conservatory and in 1944, he started as a composer in the film studios in Zlín. This city was crucially determined by the Baťa shoe factory. In the first half of the 20th century, Tomáš Baťa took great care of the complex social status of his employees; their involvement in culture and sport and their abstinence from alcohol and tobacco. The city includes an entire district of Baťa-houses to accommodate the workers. The film studios produced advertisements: Liška cut his teeth on these and on animated films.

Here, he encountered his first important collaborators: puppet film maker Hermína Týrlová, and a Meliés-style magician who created dreams between animated and live action films – Karel Zeman. With Zeman, the young Liška soon entered the realm of experiments. When glass, the pride of Czech export, needed advertising, Zeman made an imaginative short film titled INSPIRATION (Inspirace, 1949). The sounds Liška is able to merge with the glass material show how far he was able to think through the process of glass-making – from liquid material to solid, and from there on to specific forms – here still in the traditional orchestral instrumentation, with only the addition of the realistic sound of water.

Private Man

It is difficult to identify the influences that were crucial for Liška. Over the course of his entire career, he gave only one interview that was published in print – his entire story is only being reconstructed after his death. Until this day, it includes not only his extensive oeuvre, but also a number of uncertain periods and a general lack of information.

What is certain is that Liška decided to make film music his exclusive occupation. “I only write under moving pictures,” he would say. In this, he differed from remarkable composers like Luboš Fišer, Svatopluk Havelka, Jan Novák, Jan Klusák, or Ilja Zeljenka, who also left their distinctive imprint on film music, but were more active as authors of concert music. Liška, it seems, did not miss this. By the end of the 1950s, he had acquired a reputation as a distinctive, fast-working composer who possessed both professionalism and a remarkable invention.

The beginning of his artistic maturity is marked by his first feature-length collaboration with film-maker and animator Karel Zeman: THE INVENTION OF DOOM (Vynález zkázy, 1958). For this Jules Verne adaptation, Liška combined acoustic instruments and early electronics: the orchestra’s dramatic narration is complemented by ‘walkie-talkies’ made by early oscillators and the industrial rhythms of motorised valves. Just like Verne, then, Liška anachronistically combined technologies from different time periods. That was his strong point: he belonged to the era of symphony orchestras, but he greatly enjoyed experimenting. He also suggested edits to the director, increasing the pacing of the entire film.

It is of course extremely rare that a composer acts as a parallel dramaturg (editor?) for the film, but that was exactly the position Liška began assuming. He conceived of music as one of the dramaturgical methods film has at its disposal. For him, it was much more than an illustration or expression of atmosphere. THE INVENTION OF DOOM became the most successful Czechoslovak export film altogether. To this day, it retains cult status in Japan.

With features like the subtle drama AT THE TERMINUS (Tam na konečné, 1957) or THE WHITE DOVE (Holubice, 1960), lyrical impressions from the life of a sculptor, he became the most in-demand Czech film composer. Throughout the 1960s, he stuck to an almost unbelievable rhythm: he scored eight feature films a year, and a number of shorts on top. This decade also saw the creation of his most fantastic works.

A Man from the Twentieth Century

“You have to understand there are things robots aren’t fit for,” says the astronaut in the first large-scale Czech sci-fi. Liška knew no one could say what space sounded like. That is why he wed his experiments in electronic music to the cosmos. He was one of the pioneers of electronic music not only in Czech film, but in Central Europe. The opening credits to THE MAN FROM THE FIRST CENTURY (Muž z prvního století, 1961) list Zdeněk Liška under “electronic music”, but also Jaroslav Svoboda as the “author of the electronic instrument” – Svoboda prepared the composer’s technical setup. Liška’s search for sounds made use of oscillators and filters: he carefully selected the sounds he would use. Suddenly, sci-fi was an amply supported genre even in Czechoslovakia: during the cold war, both parties were openly competing in the space race.

For the satirical comedy THE MAN FROM THE FIRST CENTURY, Liška created distinctive sounds (rather than music), but he had larger expanses and more complex means at his disposal when scoring the existential sci-fi IKARIE XB-1 (1963; the remastered version was screened at the Cannes Festival in 2016). Several layers of pulsations and tones complete the scenes both inside the Ikarie space ship and in outer space. Liška evokes warning sirens; communication signals both strong and weak; the trembling of material; nervous responses to sudden impulses; and most of all, something uncertain and unknown.

There is even a dance party scene in the futuristic spaceship: the astronauts do not make contact while moving; the important thing is the repeated flowing rhythmic figure. The harmony is more impressionist, but generally, Liška quite precisely captured rhythm as the timeless axis of dance. He never used electronic sounds for melodies: they were used exclusively for their own world of rhythm, drones, and abstraction. IKARIE XB-1 is an adaptation of a novel by the Polish writer Stanisław Lem, which is why the music – arranged into a suite – was first published by the Polish public broadcaster’s label Bolt Records, as part of their Polak melduje z kosmosu compilation (2016).

Another significant chapter is Zdeněk Liška’s involvement with Jan Švankmajer. Švankmajer, born in 1934, studied puppetry, and his aesthetic was formed by the very influential Czechoslovak Surrealist Group, to which he remains loyal to this day. His films always critique a passive approach to life, throwing doubt on the ordinary, celebrating imagination, proposing a latent revolution, and declaring “animation as a magical act”. Together, they made ten short films that belong with the classics of non-conformist art of the late 20th century: the Kafkaesque THE FLAT (Byt, 1968), in which animated objects grind down their owner; JABERWOCKY (Žvahlav aneb šatičky slaměného Huberta, 1971), a tribute to Lewis Carroll; DON ŠAJN (1969), an hommage to old puppet shows; or LEONARDO’S DIARY (1972), a study in societal decay through the medium of archive footage. The music for LEONARDO’S DIARY is one of only few exceptions: it was published in Czechoslovakia as the Suite for Brass Quintet.

Jan Švankmajer gives us valuable insights into Liška’s life. “Mr. Liška had an editing table at home – that was exceptional. He took the film home and then examined and measured it at his table for so long he discovered rhythms I didn’t even know about. The fact that he made rhythm such a central component of his music was very convenient for me. I think he knew how to capture a rhythm other than the obvious one: he discovered in the material the rhythm of its soul.”

The depiction of the beginnings of the Holocaust THE SHOP ON MAIN STREET (Obchod na korze, 1965) was the first Czechoslovak film to receive an Academy Award. Not even this brought the Czechoslovak labels to publish Liška’s music – Jewish and Slovak motifs in an original transformation. An LP was made in the United States – in Czechoslovakia, it was only a vinyl single (today a coveted collectors’ item).

Screenwriter and director František Vláčil was one of the most important figures of Czechoslovak cinematography. Liška worked with Vláčil for almost twenty years: they made nine features together. IN THE VALLEY OF THE BEES (Údolí včel, 1968) and the famous MARKÉTA LAZAROVÁ (1967), they made great creative use of the tension between pagan music, the first notes of Christianity and the sounds of the real world. Apart from a few stage projects, Liška wrote no music other than film music: all the more, then, he let cinematography inspire him to create the best music he could. His film scores included his response to modernist composers: we can hear this in the music to the pagan love scene in MARKÉTA LAZAROVÁ.

Interest from Abroad

This film, like a number of others, was published on DVD in Great Britain by Second Run, reminding the cultural world about the somewhat hidden heights of the Eastern European sixties. The English musician, producer, and Czechoslovak-new-wave-cinema enthusiast Andy Votel is instrumental in these developments. With Finders Keepers Records, he began publishing extraordinary old soundtracks: not a single one of them were re-editions, they were all published for the first time. He faced several obstacles: overcoming copyright hell and finding a quality source, as the original magnetic tapes were predominantly lost.

That was also the case of Zdeněk Liška’s films: only the music for THE CREMATOR (Spalovač mrtvol, 1968) and the imaginative fairy-tale MALÁ MOŘSKÁ víla (The Little Mermaid, 1976) was published in Czechoslovakia. Both of these films have a very attractive sound-world. For the most brutal scenes in THE CREMATOR, a horror with comedic elements, Liška intentionally composed music of illusive beauty; a waltz whirling as if one were entering a grand ball. The music for THE LITTLE MERMAID, on the other hand, takes its cues from the underwater world: acoustic effects, electronics, echoes. The discs published by Finders Keepers in 2011 and 2013 inaugurated a new wave of international interest in Liška.

But this wasn’t the first time someone abroad had discovered Liška. Identical twins Stephen and Timothy Quay have been fixtures on the world art and cinema scene since the 1980s. They discovered Zdeněk Liška and Jan Švankmajer’s oeuvre while preparing a film about Czech surrealism in Prague. There is something romantic about their discoveries of film music: “We always went to the cinema with a tape recorder,” they say. They are among Liška’s most fervent admirers: their private archives include the soundtracks to a number of films. They legally recycled Liška’s music and used it in films such as THE CABINET OF JAN SVANKMAJER (1984) or THE PHANTOM MUSEUM (2003). With the Quay brothers, Liška entered the context of international contemporary art; new generations and societies of audiences. At their group exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2012, for example.

Music from Inside Films

The new portraiture of Zdeněk Liška in the Czech Republic has gone as far as the documentary film MUSIC: ZDENĚK LIŠKA (2017), directed by the author of this text. It brings samples from dozens of feature films and valuable personal testimonies from a number of artists: Jan Švankmajer, Juraj Herz, the Quay brothers – but also Jára Tarnovski, for example, a contemporary electronic musician who remixes Liška’s music into mixtapes for internet radio stations.

If I may be allowed to append a personal remark, the making of the film included several highlights. One of these were my conversations with Jan Švankmajer and Juraj Herz, the latter of whom – author of the legendary new wave jewel THE CREMATOR – died in 2018. The documentary is thus the last record of the famous director before his death. They both remember Zdeněk Liška as a masterful artist, who in a friendly and helpful manner listened to the director’s conception, only to then bring an entirely unique and different result – a film score

as his own analysis of the work.

The second highlight was mastering the sound track for VOLÁNÍ RODU, an adventure film made in 1977: Liška took this prehistoric tale and wed to it electronic sounds including bass pulsations and drones. And then there was the collaboration between myself and the main co-author of the film, Jan Daňhel – editor and member of the Czech surrealist group. It is thanks to him that this tribute to Zdeněk Liška, at times displaying an inclination towards experimental methods, could see the light of day.

Liška expected his music to sound from inside films: thanks to its unique characteristics, however, it has separated itself from the image, now often presented as an autonomous work.