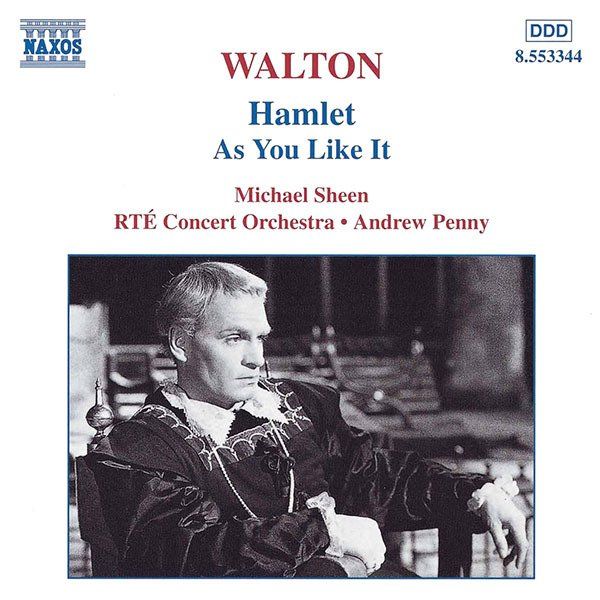

William Walton 1902-1983

Writing music for the screen is undoubtedly a specialised job. To begin with, the composer is rigidly disciplined in his work by the time factor. For example, in HAMLET (as in all other films) my first contact with the production was the arrival of the script. This meant that I could obtain at least some idea of the treatment envisaged by the producer-director, in translating this monumental work into celluloid. An occasional visit to the film set also gave me some impressions of how the project was coming along.

The first showing in this country of Sir Laurence Olivier's production of RICHARD III attracted a great deal of attention, and with justification. It is an impressive spectacle in whatever form it is experienced: on television, on the theater screen in Vistavision and Technicolor, or listening to the soundtrack released by RCA Victor. Sir William Walton wrote the score, as he had for Sir Laurence's previous Shakespearean productions of HENRY V and HAMLET. The music contains many tuneful passages that remain in the memory. Throughout the film the score performs different functions. Some of it is implicit in the scenes, such as drums and trumpets followed by organ music during the coronation, and fanfares and field drums during the battle. At times the score serves to characterize personages in the film: Anne, represented by a plaintive oboe solo against a background of strings; Mistress Shaw by a pert ditty; Richmond by a broad and stately theme in woodwinds and brass. Finally, much of the music does what it is supposed to do in any adventure film: it stings and snarls and emphasizes and creates suspense or excitement. The opening music sets an atmosphere of pomp and splendor which cannot be mistaken for anything but English. A broad tune in the tried and true Elgarian vein appears here for the first time; it is again heard near the end of the picture when we approach the camp of Richmond, the future Henry VII; it also ends the picture over the credits. The picture proper opens with a shot of the crown, portrayed musically by a high tremolo in the strings. The scene shows the coronation of King Edward IV. Brasses alternate in rhythm with the shouts of the nobles as they acclaim the new king. The last note of the brasses is picked up by the voice of the archbishop as he intones the benediction. The sounds of gay music and the people shouting in the distance recede as Richard, the king's brother, is left alone in front of the throne. Richard turns to the camera and in his famous soliloquy "Now is the winter of our discontent ..." he reveals his cold-blooded designs to gain the crown. Sir Laurence's voice is tremendously impressive here as all through the rest of the play. He handles it, in fact, like a versatile instrument at all times fascinating and expressive. The employment of music during this soliloquy seems curiously belittling to the power of the acting, both visually and vocally, to carry the scene. At the words: "Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths ..." the music enters discreetly in back of the voice, and when the lines refer to the "lascivious pleasing of a lute" we hear the sound of a lute. This surely seems to be an extreme case of gilding the lily. The soliloquy rises to a shrieking climax — followed with great effectiveness by the soft chanting of monks approaching in the street. They form part of a funeral procession in which Anne follows the corpse of her husband recently slain by Richard. With Anne we are introduced to her little oboe tune as background. Throughout the film it faithfully appears as she appears, and does not alter its form materially however cruel the straits in which she finds herself. It remains sad and resigned even during the weirdly stirring scene in which Richard woos and wins her. In many instances the music strongly emphasizes the grimness of the situation: Clarence being conducted to the Tower after a hypocritical expression of commiseration by Richard; a sting as Anne spits in Richard's face; shock music as the scene changes abruptly to the dark exterior of the Tower in which Clarence is imprisoned; a musical shriek as Richard turns to his young nephew when the boy playfully refers to Richard's malformed shoulders. The treatment is far from subtle, but the music does what it is supposed to do: it shocks. A beautiful transition is effected, both pictorially and musically, as the scene of Clarence's violent death in a wine barrel shifts to the bed chamber of the ailing King Edward. Through a dissolve two lighted Gothic windows appear and the music changes to a soothing organ piece. The organ is presumably used purely for instrumental color; it is not employed, as it was during the coronation, as a sound emanating directly from the scene. On second thought this may appear to be somewhat of a confusion of styles, but on first hearing it certainly is effective. The battle on Bosworth Field which concludes the picture invites, of course, comparison with the battle of Agincourt staged in HENRY V. Sir William Walton's task was thornier in RICHARD III for this battle is more dispersed in nature and less grimly fought. In contrast to the treatment in HENRY V where music supplied all the sound during the fighting, sound effects are used in conjunction with the score in RICHARD III. If this description of a battle seems less exciting than the other, that is most likely due to the nature of the engagement which was sporadic and finally ended in a general cessation of fighting when both parties united against Richard. The music graphically shows the slowing down of hostilities as the two armies stop combat and the soldiers embrace. Richard, on foot, is cornered. The only sound heard is his breathing — a chilling effect. He is set upon and mortally wounded, and the music takes up at this point. The musical treatment of this sequence rivals in obviousness that of many a less spectacular film: as Richard throws himself from side to side in his death agony each movement is accompanied by a sharp stab in the orchestra. He raises himself for a final effort and then sinks down as a 'cello solo slithers down with him. We may smile at some of the effects employed in the old melodramas, but the technique is still very much alive, apparently. The release of the sound track on records affords a welcome chance to hear the drama unfold at the listener's leisure. It brings home forcefully a virtuosity of Sir Laurence's acting and the tremendous range of characters encompassed by his supporting cast. The excitement of the drama comes through vividly.

This short choral work was in fact penned by George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) for the 1941 British film Major Barbara and may be heard on the soundtrack, approximately ten minutes before the end of the film, during a brief scene showing Shaw’s vision of a socialist post-war Utopian world. The film is a reworking of Shaw’s 1905 stage play of the same name made by the Hungarian director/producer Gabriel Pascal (1894-1954).

CD Reviews

William Walton and Laurence Olivier first met in 1936 when Olivier co-starred in Paul Czinner's production of As You Like It with Elizabeth Bergner, Czinner's wife. In 1943 Olivier decided to put his Henry V on film and approached Walton to write the music. This was the first of three films on which Walton and Olivier collaborated together; the others were Hamlet, written in 1947 and released in 1948, and Richard III in 1955. The association was a happy one and Olivier said of Walton's music. 'I have always said that if it was not for the music, Henry V would not have been the success it was.'