Things to Come

English Music Festival May 2014 Pre-Concert Talk

Introduction

SLIDE 1. Good Afternoon. Thank you for coming today. Over the next hour I would like to share with you my analysis of primary source materials relating to Bliss’s debut film score Things to Come. As well as covering old and some well-trodden ground there are new findings to present on the score and I hope these will be of interest to you. I plan to read from notes as there are a lot of details to convey.

There is no shortage of source information covering the history of

Things to Come, both the film and the music. Bliss devoted a number of pages about his involvement with H.G. Wells’s project in his autobiography As I Remember and there is also a substantial piece devoted to the concert suite in Bliss’s own ‘Selected Writings’ which span the period 1920 to 1975. Importantly, numerous private letters were exchanged between Bliss and Wells during the years the film was made, 1934 to 1935. These can be found in the Wells’ archive in Chicago and the Bliss archive in Cambridge. The composer spoke many times on both TV and radio about his film music, even as late as 1972 when a guest on Roy Plomley’s

Desert Island Discs. If you have not heard this interview it can still be accessed through BBC iPlayer Radio.

John Huntley

My interest in researching the music to Things to Come started around the year 2000 when I was preparing an article about Laurence Olivier’s Henry V for the centenary year of Sir William Walton. I was very fortunate at the time to get help from a man called John Huntley. John started in the film business as a tea boy joining Denham & Pinewood Studios shortly after leaving school at the age of 16. He served in the RAF during the Second World War as a wireless air gunner and after the war returned to work at Pinewood, initially as a sound technician and later as a technical assistant to the conductor Muir Mathieson. John was very keen to share with me some of his vast knowledge of British Film Music. He related to me an account he had heard directly from Muir Mathieson as to how the opening Christmas carol scene in Things to Come was recorded. He said this took place in the Scala Theatre off Tottenham Court Road London toward the end of 1935. The London Symphony Orchestra chorus were standing in the theatre boxes and Mathieson was conducting in front of a cinema screen up on the stage. The Scala Theatre no longer exists but if you are curious to know what the interior looked like I recommend you watch the Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night; the Scala was used for the stage concert shown in the film.

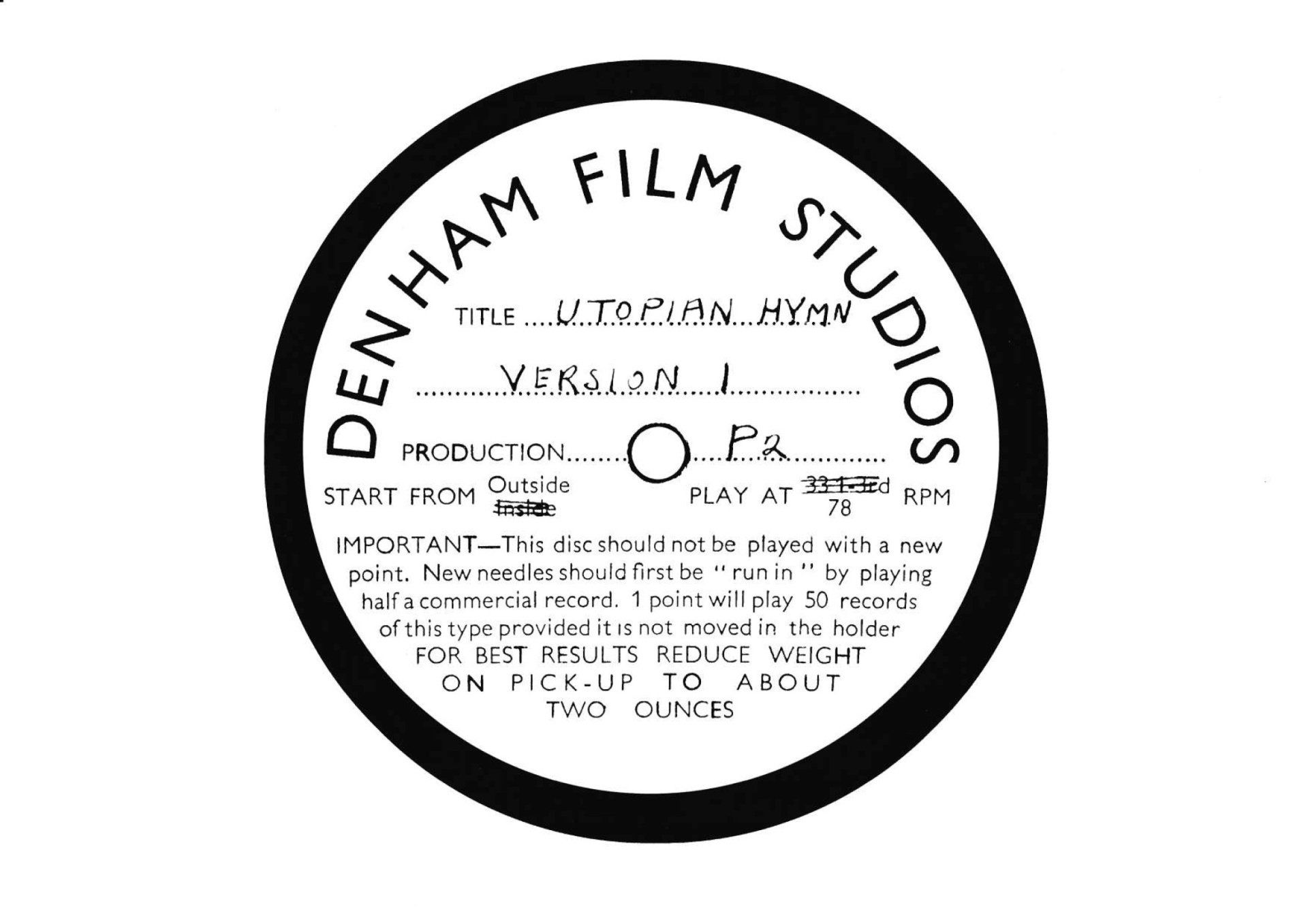

John asked me if I would be interested in material from the film Things to Come. As well as photographs and the first-hand stories told to him by Muir Mathieson, to my amazement he brought out from his archive a collection of shellac records, including a puzzling playback recording made by Denham Film Studios titled ‘Utopian Hymn’. He kindly made a tape cassette recording of all his discs and arranged to have the record labels scanned in high definition. I received this package from him plus a sheet of paper upon which he had written the words: “The Great Mystery Records. Why?” In this talk I will attempt to answer John’s question to me.

Whither Mankind

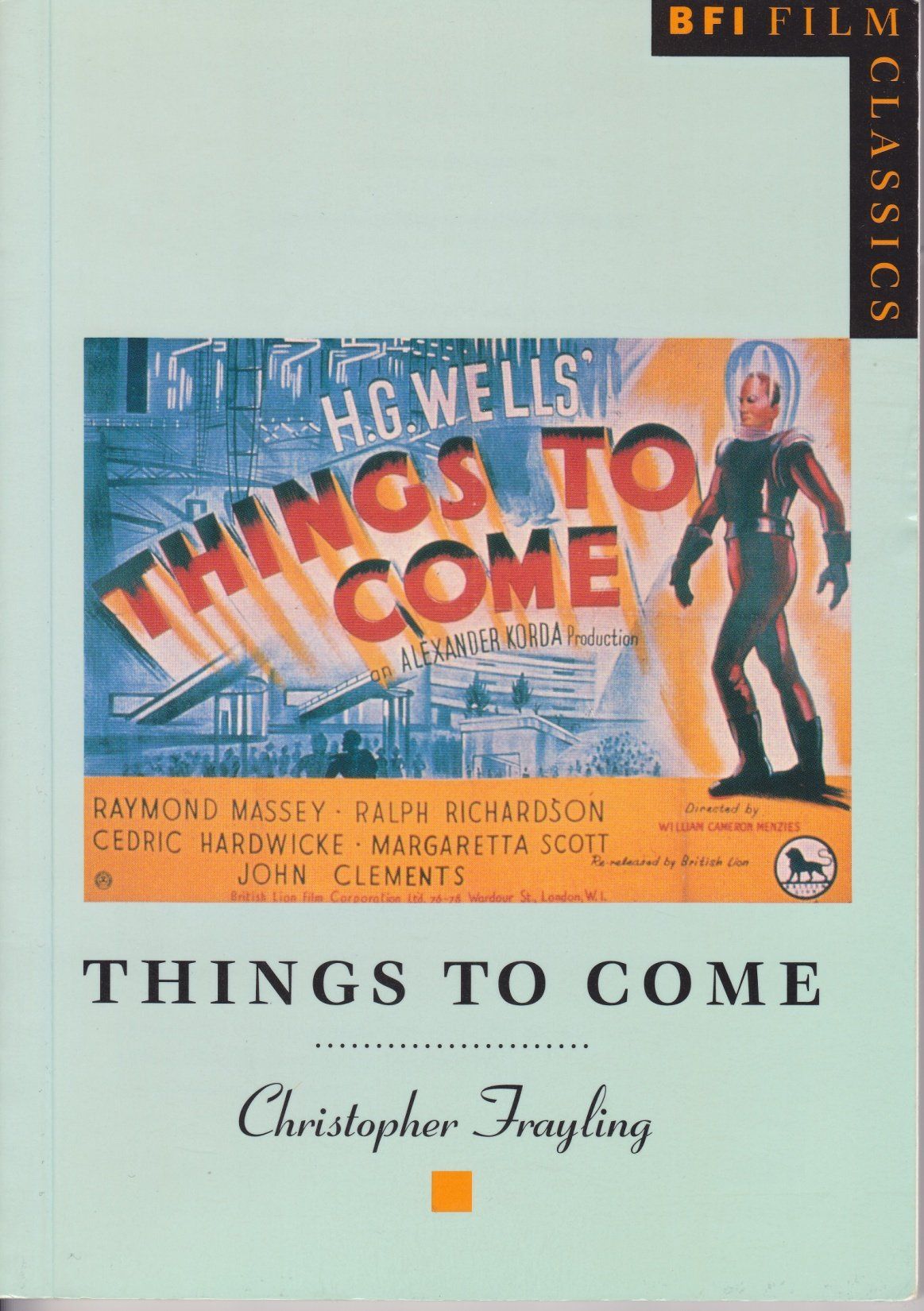

The book The Shape of Things to Come: The Ultimate Revolution was first published in September 1933. SLIDE 2. My own copy was printed in 1936, the same year as the film’s release. The Hungarian film producer Alexander Korda, co-founder of London Film Productions, expressed an interest in turning the book into a film and toward the end of 1933 he met up with Wells in a tea-room of all places in Bournemouth. Korda purchased the rights to make Things to Come and The Man Who Could Work Miracles. He also showed an interest in adapting for the screen two other stories by Wells: The Food of the Gods and The New Faust. SLIDE 3. It is reported that Wells acknowledged the deal with London Films, worth over half a million pounds in today’s money, by putting his signature on a penny-post card.

Several months later during March 1934, at the Royal Institution in London, Arthur Bliss was on his feet giving a series of three lectures on ‘Aspects of Contemporary Music’. Wells happened to be in the audience during the second of these lectures in which avant-garde composers were discussed. Bliss touched upon what he termed “the machine complex” in music citing Arthur Honegger’s symphonic movement

Pacific 231. He illustrated his thoughts by playing extracts from gramophone records, including Prokofiev’s symphony no. 3 from 1928. Which particular section he played is not clear from the text of his talk but I would guess the fourth movement which like Prokofiev’s second symphony onwards is in the

style mechanique influenced by Honegger. Bliss also read out contemporary poetry to the audience, Steven Spender’s ‘The Express’, a poem about a steam train speeding through the landscape of Britain.

Wells was greatly impressed with Bliss’s modern outlook and may have been attracted by these particular references in contemporary poetry and music to machinery. Following the talk the two men met up for lunch. There and then Wells extended an invitation to Bliss to collaborate with him on the film by writing the score. Bliss consented and within a matter of weeks had set to work in his studio on the first floor of his London home overlooking Hampstead Heath. Incidentally, some sources say that H.G. Wells also gave a lecture on the same occasion as Bliss in 1934. However, after consulting with several experts I can say this was not true. Wells first lectured at the Royal Institution in January 1902 and again during November 1936, two years after Bliss, when Wells talked about creating a new social institution which he termed ‘The World Encyclopaedia’. Sounds very much like Wells anticipated Wikipedia.

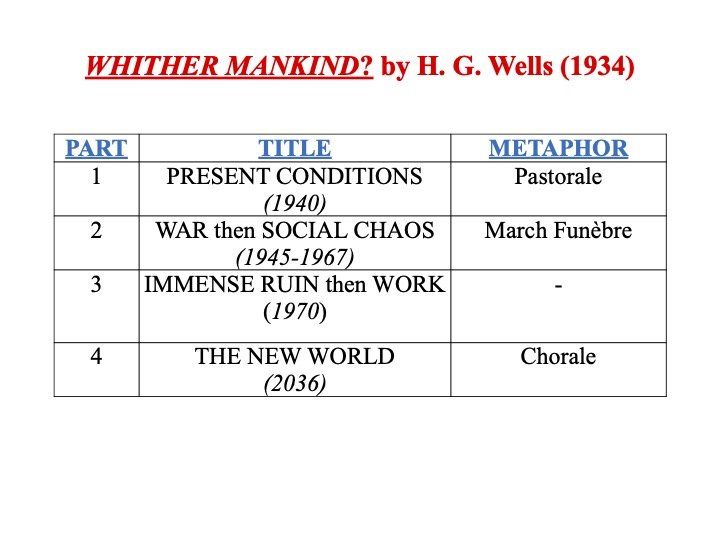

At the outset Wells provided Bliss with a draft film treatment titled WHITHER MANKIND? in which he Wells had defined all the required music cues. The film was structured in four sections with musical metaphors assigned to the parts. SLIDE 4. Part I, PRESENT CONDITIONS, opened in 1940 and had the metaphor ‘Pastorale’; Part II covered universal WAR extending over a 20 year period which then degenerates into SOCIAL CHAOS. This part was likened by Wells to a ‘Funeral March’ ; Part III deals with the prolonged years of RUIN and PESTILENCE followed by the WORK SERIES in which giant machines controlled by scientists create THE NEW WORLD in 2036, 100 years into the future. The metaphor assigned by Wells to Part IV was ‘Chorale’ which I will return to. Interior filming did not start at Elstree Studios until September of 1934 and exterior work on the Denham back-lot took place the following year between March and September 1935.

The March: Horrie’s Story

Bliss’s imagination was fired purely by the story and I think it fair to say he provided music exactly according to Wells’ specification. What was in his mind when he composed the music? To give you some idea I would like to tell the story about the genesis of his famous ‘March’ which we are all familiar with.

In the opening part of the film there is a scene in which a little boy, Horrie Passworthy, is with his dad outside the family home. It is the evening after Christmas and little Horrie has received a tin drum, some soldiers and a toy canon as presents. His father is an air raid warden. The threat of war hangs in the air. Father kisses his son goodbye, salutes him and goes off to perform his night-time black-out duties. SLIDE 5. Horrie is left alone outside the house marching up and down tapping his tin drum. Then we see a scene of the little boy marching in front of a huge backdrop. SLIDE 6. Behind him we see the giant shadows of soldiers marching to war. Then comes the full force of the air raid on the town which is quickly reduced to ruins. At the end of the bombing scene we see little Horrie lying dead among the smouldering rubble. SLIDE 7. Gas and incendiary bombs have been dropped. Over all of this we hear Bliss’s ‘March’. Here is what the composer said in one of his early letters to Wells and I quote: “12 April 1934. I have struck out various themes, for the opening, for the children’s party, for the outbreak of war, which has dramatic value – for instance the music that accompanies Horrie’s marching around with the drum becomes the music of the war – as though his little Tom-ti-Tom sets the whole world alight. The audience will not appreciate this, but this sense of development is pleasing to the musician” unquote. So now you know Bliss’s ‘March’ was not intended to be a happy one. Bliss knew all too well the horrible effects of warfare having lost his younger brother Kennard in the Great War and he himself was wounded at the Battle of the Somme. Ten years after the war Bliss was still suffering nightmares of being back in the trenches. One further observation on this particular film passage, it is startling how accurately Wells predicted the near future such as the London Blitz of 1940 and 1941. You could even draw a parallel here between the scene I’ve just described and the chemical attacks against civilians and children witnessed in the present day.

Around June 1934 Bliss and Wells met at the composer’s home to discuss progress. Bliss played the key themes on his piano to which Wells reacted and later formally responded in writing. I quote in part from one of Wells letters to Bliss, this one dated 29 June 1934: “Of all the early part up to and including the establishment of the Air Dictatorship I continue to be confident and delighted. But I am not so sure of the Finale”. He went on: “I do not feel that what you have done so far, fully renders all that you can do in the way of human exaltation. It’s good – nothing you do can fail to be good – but it is not the marching song of a new world of conquest among the atoms and stars.” Bliss replied almost immediately by saying he agreed the finale was quote “by no means right” and that it was “no easy matter that can be done like a piece of carpentry”. What strikes me as important from this exchange of letters is that a “marching song” was played to Wells during June 1934 and he was pressing Bliss for something greater to suit the film’s climax.

Suite From Film Music (1935)

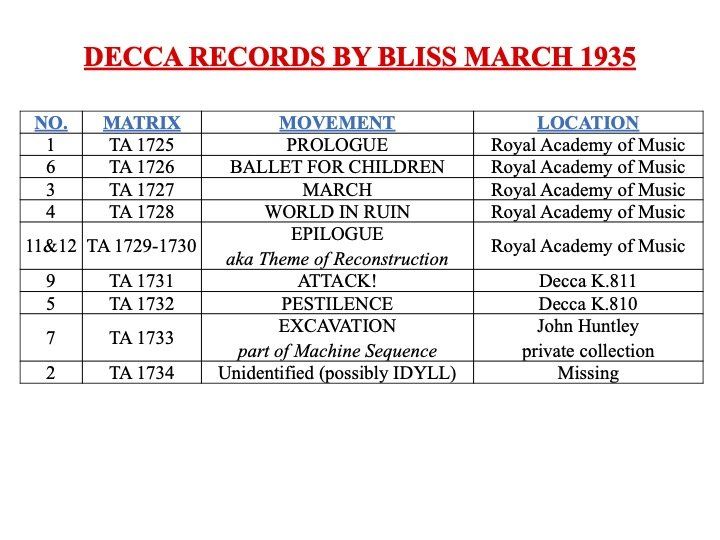

Two major events occur during the following year 1935. First, Bliss went into Decca’s Thames Street studios in London on 3rd March to pre-record his film score with the London Symphony Orchestra. SLIDE 8. Wells wanted the music to be an integral part of the design and his aim was to construct the film around it. Bliss made ten single sided 78 rpm records on that day, four sides of which were later commercially released. SLIDE 9. Samples of the recordings were given to the sponsor London Films and, as will become clear, to Sir Henry Wood.

Information about Bliss’s Decca records can be found on microfilm at the British Library, including the matrix numbers which are hard stamped onto the run off groove area of the record.

SLIDE 10. The record labels were also marked with a number ranging between 1 and 12 plus the general heading ‘The Shape of Things to Come’. As mentioned, Bliss recorded ten sides in total. So given the numbers range up to 12 it looks like he planned to record two other tracks, numbers 8 and 10. Maybe Bliss simply ran out of time on that day and had to call a halt to the session work. By good fortune six of these ten Decca records surfaced by accident in 1991. They were found in pristine condition and stored in among other shellac records belonging to Sir Henry Wood at the Royal Academy of Music. This enormously valuable find was made by a music student, Jonathan Dobson, who later produced and narrated an excellent radio broadcast for the BBC which aired in 1996 titled ‘More Things to Come’.

Having heard Bliss’s music on record it can be inferred that Sir Henry Wood approved the first public performance at his Promenade Concerts. This took place at Queen’s Hall on 12 September 1935. The concert programme luckily contains a page of descriptive notes written by Bliss himself. SLIDE 11. A suite comprising the following seven movements was performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra with Bliss conducting: ‘Prelude’ later re-titled ‘Prologue’, ‘Ballet for Children’, ‘Idyll’, ‘March’, ‘Melodrama no. 1: Attack’, ‘Melodrama no. 2: Desolation’ and the ‘Final Theme of Reconstruction’ aka ‘Epilogue’. I was privileged to obtain from the BBC Symphony Orchestra Music Library a sheet of paper detailing the wind and percussion instruments on which the duration of the 1935 Prom premiere was written: total time 23 minutes. This by the way contrasts with 17 minutes for the shorter modern day version of the suite.

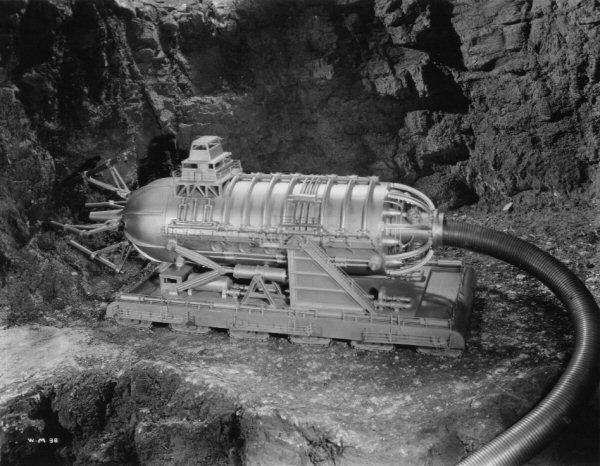

When comparing Bliss’s pre-recording of the film score at Decca with the concert suite performed at the Proms the records can be matched up to the movements with two notable exceptions: matrix numbers TA 1733 and TA 1734. This prompted me to look again at the test pressings given to me by John Huntley. To my delight he owned a copy of TA 1733 with the word “MACHINES” scrawled on the label. This record contains in fact the so-called ‘Excavation’ music which accompanies the scene where hills are mined. Giant machines which look like vacuum cleaners are seen creating the subterranean city of the future. SLIDE 12. In the film a short extract from the ‘Excavation’ music precedes two other related sections underscoring what H.G. Wells termed the “Work Series”. The other sections were ‘Building of the New World’, music which Bliss later recycled as ‘Entry of the Red Castles’ in his ballet Checkmate and ‘Machines’, which Bliss later incorporated into his definitive six movement concert suite published by Novellos in 1940. Bliss was puzzled and perplexed by Wells advice to him on this particular sequence: ‘Remember that the machines of the future will be absolutely noiseless’ he was told. The composer was left pondering what to do. “How to write music that expressed inaudibility?” I’m tempted to jest here and mention John Cage’s silent composition “4 minutes 33 seconds”.

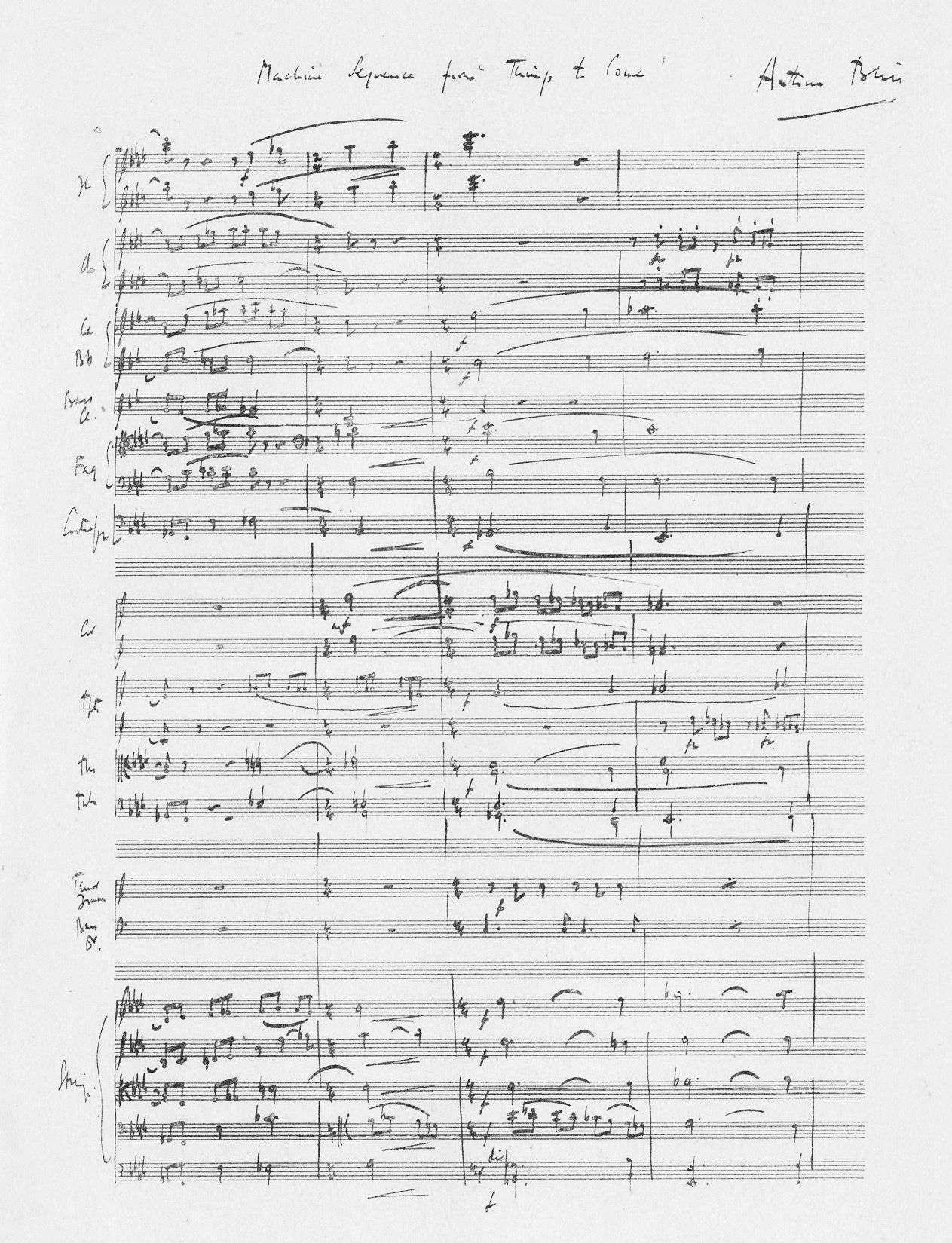

I am pleased to say that during the course of my research I uncovered a single page of unpublished manuscript relating to Bliss’s ‘Excavation’ recording from 1935. I discovered this in a book by the German film musicologist Kurt London published in July 1936, shortly after the film was released. It looks to me that Bliss passed on parts of his film score to this author and that the ‘Excavation’ music was probably never returned. The solitary page in question bears the composers signature and the title ‘Machine Sequence’. SLIDE 13.

So, in summary, 9 out of 10 discs or 90% of the music recorded by Bliss in 1935 has now been traced. Only one disc, Decca matrix number TA 1734, remains to be found and in my view this could well prove to be the lost ‘Idyll’ movement. What makes me so sure about this? The answer lies in another John Huntley story.

The Idyll

During the winter of 1950, just before the music department at Pinewood was disbanded, John gave a series of lectures on the topic of “music and the cinema” at the University of London. There were nine lectures in total. According to the syllabus I managed to source, during each lecture John played gramophone records to his audience, exactly as Bliss had done at the Royal Institution. In lecture no. 6 he covered early talkies, including The Singing Fool from 1928 and Things to Come. As well as Al Jolson he played a set of seven records by Bliss. These were: ‘Ballet for Children’, the ‘March’, ‘Pestilence’, ‘Attack’, ‘Machines’, ‘Idyll’ and the ‘Epilogue’. More than likely these were exactly the same recordings made by Bliss for Decca and it would appear that at this point in time, i.e. circa 1950, John possessed the ‘Idyll’ movement. What happened to his copy of the record I don’t know. I have asked John’s surviving daughter if she can help to locate this as well as his lecture notes but unfortunately all of John’s film memorabilia from his days at Pinewood were auctioned off after his death in 2003. The treasure trail to finding the lost ‘Idyll’ movement has come to an abrupt halt. By the time I got to know John in 2000 the ‘Idyll’ recording had probably slipped from his memory for he did not give me a copy.

Fundamental questions remain over where Bliss’s ‘Idyll’ music fitted in because this particular item does not feature in the surviving film print. According to Bliss’s programme note written for the Proms, movement No. 3 was quote “an Idyll of pastoral peace in the reconstructed era”, in other words a scene set in the future. In his Film Story H.G. Wells describes the music for the ‘New World’, as “gay and spacious, against which plays the motif of the reactionary revolt”. In other words there were two directly opposing themes. Details of various cuts made, including sequences which were either abandoned once filming had started or cut out before the trade show on 20 February 1936, are given in Christopher Frayling’s book published by the British Film Institute. SLIDE 14. This is a fascinating account of the film’s development and production up to the premiere in Leicester Square. My opinion is Bliss’s ‘Idyll’ music was discarded because the scene was never shot, and as a piece of film music featured for the first and only time at the 1935 Promenade concert.

The Lost Score

To my surprise the BBC Symphony Orchestra wind and percussion instrument sheet, which I previously referred to in connection with the 1935 Prom, revealed that the music parts were provided by John Curwen & Sons Ltd. I should explain that originally Chappell & Co. owned copyright for the film music and this was later transferred by arrangement to Bliss’s main publisher Novello & Co. Curwens must have printed the orchestral parts on behalf of Chappells during 1935. I only mention this because for a fleeting moment when I first saw that sheet of paper from the BBC I wondered if the original score may still exist somewhere in the Curwen archive. Searches for the lost score have in the past focused mainly on Pinewood Studios and Bliss’s St. John’s Wood home after the composer’s death. Sadly I was to learn that when the company collapsed in 1969 the Curwen music archive was shipped over in crates to New York where it was eventually destroyed. I am convinced that with the sole exception of the ‘Attack on the Moon Gun’ manuscript, which I will discuss in a moment, Bliss’s autograph score was destroyed, either accidentally during World War 2 or deliberately when the Rank Organisation collapsed during the 1950s. There are reports of the music department out-building at Pinewood being bulldozed with the scores still inside, including important film music by the two Williams - Alwyn and Walton. Bliss states in his autobiography that some of his manuscripts stored in a warehouse were hit by a bomb during the Second World War. He points out loosing the manuscript of his concerto for piano, strings and tenor voice written in 1920. There is no mention however in the book of loosing

Things to Come.

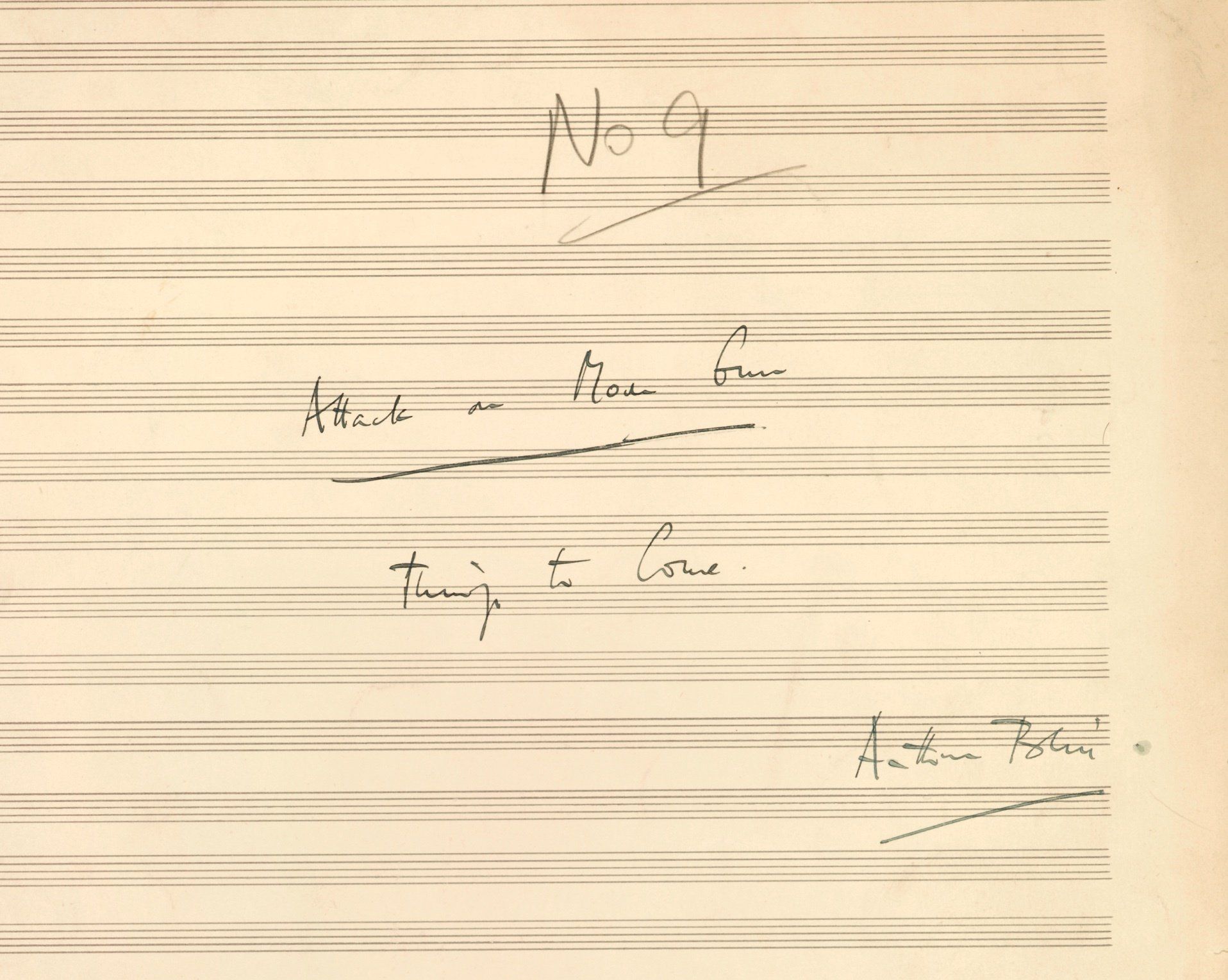

Attack on the Moon Gun

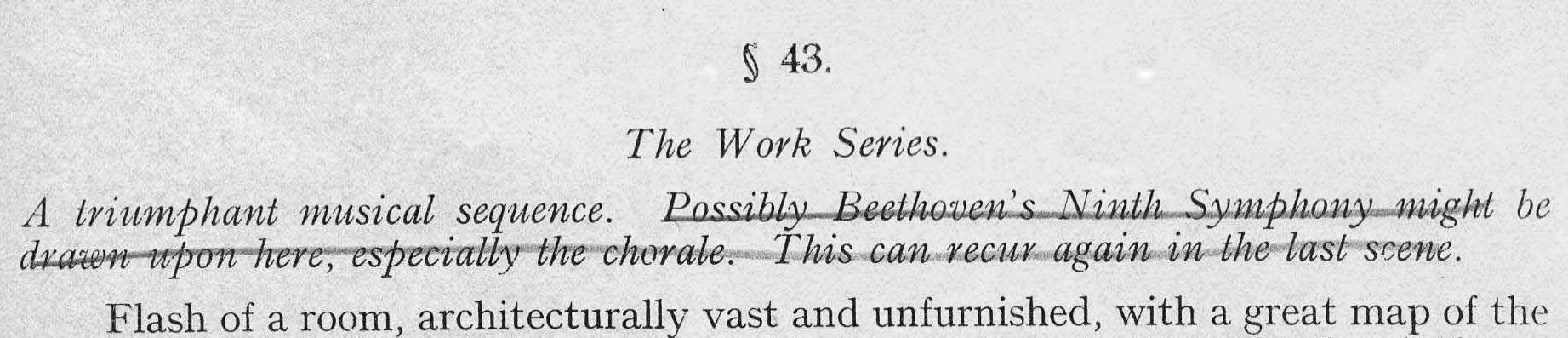

Fortunately, as mentioned, a single complete movement from the autograph score has survived. This was donated by Lady Gertrude Bliss to Cambridge University Library along with Bliss’s other manuscripts and now resides within the Music Department. This score plus Wells’s original film treatment WHITHER MANKIND? offer a number of vital clues about the music in particular changes to Part 4 of the film. The surviving score section is titled ‘No. 9 Attack on the Moon Gun’. Wells’ musical metaphor for this scene was quote “a Chopinesque Revolutionary Etude”. I need to return in time at this point. Bliss received updated script details during October 1934, six months after he commenced composing. By all accounts there was a fundamental reworking of the storyline following a critique of the first production script by one of Korda’s own writers, the Hungarian novelist and playwright Lajos Biró. Biró together with the staff writer John Burch worked on the screenplay to Things to Come but neither received a screen credit. In his letter to Bliss dated 17 October 1934 Wells states: “I am sending you Treatment (second version). It is very different from the first and in particular the crescendo up to the firing of the Space Gun is newly conceived.” Important clues concerning changes made can be found in two other letters from Wells to Bliss. The first of these is dated earlier 25th April 1934 when Bliss was first setting out his principal themes. At this time H.G. Wells was just about to set sail from Southampton to New York on the SS Washington for an historic meeting with President Roosevelt. Wells’ letter looks to be written in a considerable rush and for that reason is difficult to decipher. My reading of this letter, the original of which is in Cambridge, is as follows quote: “Frank will have advised you duly of the revision of the latter part of the Film. It cuts out the Chorale & demands Original Bliss” unquote. The Frank in question here is Wells’ son Frank Wells who worked as assistant art director on the film and the “Original Bliss” demanded is in my opinion the “Moon Gun” music cue, the last section to be composed. What exactly was Wells referring to when he said “It cuts out the Chorale”? After some painstaking detective work I discovered the answer in a proof copy of the film treatment held by the University of Illinois Chicago. The relevant chapter is headed “The Work Series” and the opening line reads as follows, quote: “A triumphant musical sequence. Possibly Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony might be drawn upon here, especially the chorale. This can recur again in the last scene.” The last two sentences have been scratched out. SLIDE 15. Apparently Wells originally wanted to employ Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ but dropped this favouring turning the Moon Gun scene into one of conflict and revolt. John Huntley’s test pressing of the ‘Utopian Hymn’ needs to be brought into focus at this point. The hymn which I mentioned right at the start of my talk comprises four verses and is written for mixed choir and organ. I have been told this was once played to Lady Bliss and she confirmed it was not written by her husband. Only the studio playback recording survives and the few clues found on the record label. SLIDE 16. This disc was an acetate cut during the recording session to allow immediate playback as it was normal for the optical film soundtrack to be processed in the lab overnight.

The Ghost Goes West, starring Robert Donat, was the first Korda film produced at Denham while the studios and laboratories were under construction during 1935. (The official opening of the studios took place a year later in May 1936.) Things to Come immediately followed and was filmed on the Denham back-lot simultaneously with The Man Who Could Work Miracles. Production P2 on the record label ties in exactly with this shooting schedule.

Wells’ film treatment WHITHER MANKIND? includes numerous references to a crowd marching and singing their song of revolt. You may recall from earlier in my talk Wells’ criticism concerning the “marching song” after Bliss played his key themes on the piano during Wells’ visit to East Heath Lodge in June 1934. Wells describes this song as quote “the new revolutionary air or the Marseillaise”. In my view the hymn was written for the climax of the film, the Moon Gun attack, but it didn’t harmonize with the scenes of revolt filmed so Bliss went on to compose a purely orchestral piece of music. The precise context of the ‘Utopian Hymn’ is however a matter of conjecture, including who composed this.

Bliss’s signature and the No. 9 can be seen on the front page of the surviving manuscript. SLIDE 17. In total there are twelve pages of 28-stave music written in ink with pencil rehearsal marks. Who knows why only this movement survived but it appears to be the only part of the complete score never performed or recorded by Bliss himself. Maybe he held on to it for that very reason or because it was written totally out of sequence and last.

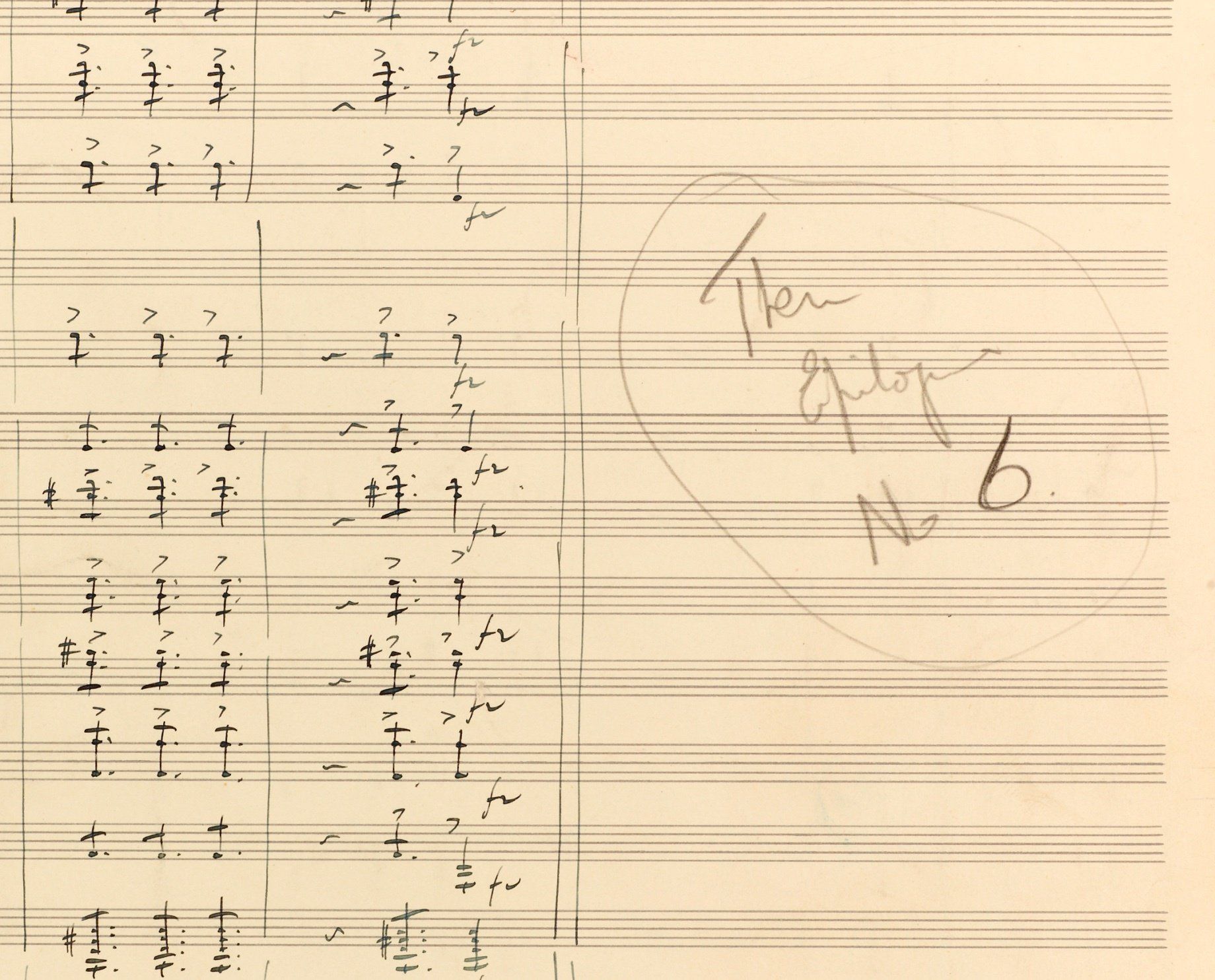

Importantly, the words “Then Epilogue No. 6” have been written in pencil by another person at the end of the manuscript. SLIDE 18. The ‘Epilogue’ features in two places in the film, accompanying the ‘Airmen Landing’ scene at the end of Part 3, which comes just before the ‘Machine Sequence’, and again in Part 4 at the very end, the final scene in the astronomical observatory. ‘No. 9’ written on the front page of the manuscript proves by the way that after editing the film score re-recorded by Muir Mathieson comprised a total of nine movements. If the ‘Idyll’ had been recorded as part of the final soundtrack there would have been ten movements altogether. The numbering found on the surviving manuscript is therefore critical to understanding what score material was used, and not used, by the music director.

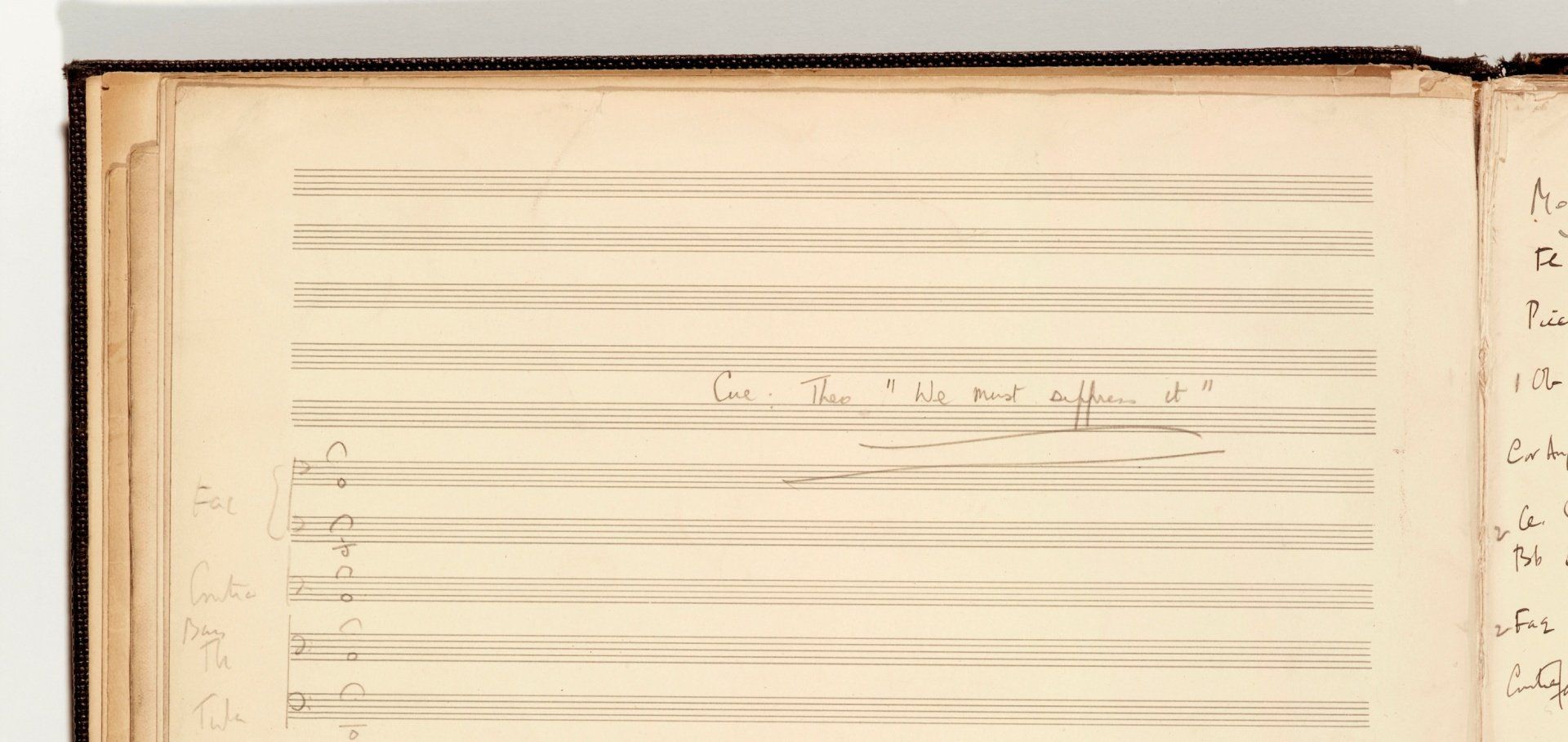

A curious detail worth mentioning here is that on the inside cover of the surviving manuscript there is a prompt in pencil which reads quote “Cue: Theo ‘We must suppress it’”.

SLIDE 19. These words, which are also repeated on the following page, appear to have been added after completion of the score. The cue in question relates to the worldwide TV broadcast made by Cedric Hardwick who plays an artisan opposed to technological progress. He is the leader of the unsuccessful revolt against the Moon Gun. Detailed analysis of this scene reveals that the first nine bars of Bliss’s score have been completely cut out by the sound editor. From my analysis of the film and its soundtrack it appears that Bliss’s ‘Moon Gun’ music cue was originally planned to feature much earlier in the scene and possibly twice. As I said, significant changes were made during final editing, including major cuts to Hardwick’s speech which runs to several pages in Wells’

Film Story.

The Epilogue Chorale

There is one further letter of significance which I need to mention now. On 7th March 1935, four days after the pre-recording session at Decca, Bliss responded to Wells saying quote “I have got the new scenario, & the end is fine. It must be very dignified – no Hollywood frills, no easy O.K’ing about it.” In total I count three separate occasions when Wells notified Bliss of script changes: 25 April 1934, 17 October 1934 and here again during March 1935 when exterior shooting commenced in earnest. Despite all these changes forced upon him Bliss remained calm and collected.

At least two recorded versions exist for the closing shot: the one heard in the film which concludes with singing “Which shall it be?”, and second, the commercial recording by Decca conducted by Muir Mathieson released after the film premiere. This latter version, not in the film, closes with a chorus a few bars long and the words “Lo, the starry sky -- Eternity!”

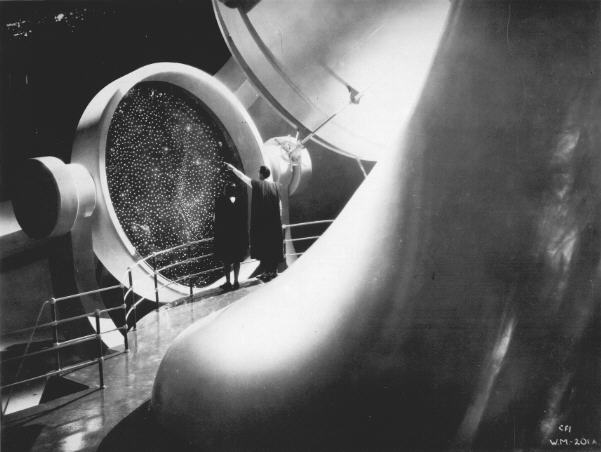

“I want to end on a complete sensuous and emotional synthesis” Wells once told Bliss. Unfortunately, after all that I’ve said, Wells did not get his end chorus from Bliss. Raymond Massey points to the stars and says “It is this or that. All the universe or nothingness. Which shall it be, Passworthy?” SLIDE 20. The musical chorus repeat his question “Which shall it be?“ and the chorus answers with an emphatic “All!”.

According to Lionel Salter, who was closely engaged with editing Bliss’s music to fit the film, this chorus was supplied by Muir Mathieson not Bliss. Salter had this say on the subject of the end chorale and I quote from one his letters written in 1978: “After the Epilogue had been composed, the producer decided that he would like a ‘heavenly choir’ to take up the final spoken words of the film - "All the universe or nothingness? Which shall it be? "; but of course the rhythm of these words wouldn't fit the music. After much fruitless discussion it was decided to give the chorus the meaningless lines "Lo, the starry skies: eternity!"” Lionel Salter confirmed in another letter that this alternative and abandoned chorus was written by Bliss himself.

There is much more I would like to share with you about the music to Things to Come, for example, facts about Bliss’s concert suite which changed content between 1935 and 1940. Those of you who attended the 7pm concert yesterday heard Sir Dan Godfrey’s arrangement first published by Chappells in 1936. I have provided summary details about the suite in the Festival Programme booklet. There is also an intriguing letter to explain in which Gordon Jacob confirmed his involvement with the film as a ghost writer. However, time is pressing and I need to conclude.

Conclusion

As you can now better appreciate the music composed for Things to Come is unconventional in terms of the practice adopted. Composing and recording the majority of the score in advance of shooting, performing a suite at the Proms, followed by pre-releasing gramophone records ahead of the film premiere, was a novel and bold experiment. The process was completely opposite to normal Hollywood practice scoring post-production.

H.G. Wells expressed huge disillusionment about his film and later conceded it wasn’t possible to blend the picture and music so closely as had been hoped at the beginning. I quote from his diary: “It was pretentious, clumsy and scamped”. Bliss was more philosophical about his contribution. He said: “In the last resort film music should be judged solely as music – that is to say, by the ear alone, and the question of its value depends on whether it can stand up to this test.” I’m certain I am not alone in thinking Bliss’s Things to Come stands up to the test.

‘Music for Strings’ which you will hear later tonight came immediately after Things to Come and was Bliss’s antidote to writing for film. He is on record as saying that he felt he was surrendering his musical individuality to the needs of the film so as a kind of mental purgative wrote ‘Music for Strings’, pure absolute music. I very much hope you will enjoy this evening’s concert.

I will end here. Thank you for your patience and attention. If there are any questions I will try and answer these. SLIDE 21.