Notes on Dragonslayer by

William H. Rosar

Originally published in

CinemaScore #13/14, 1987

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor Randall D. Larson and William H. Rosar

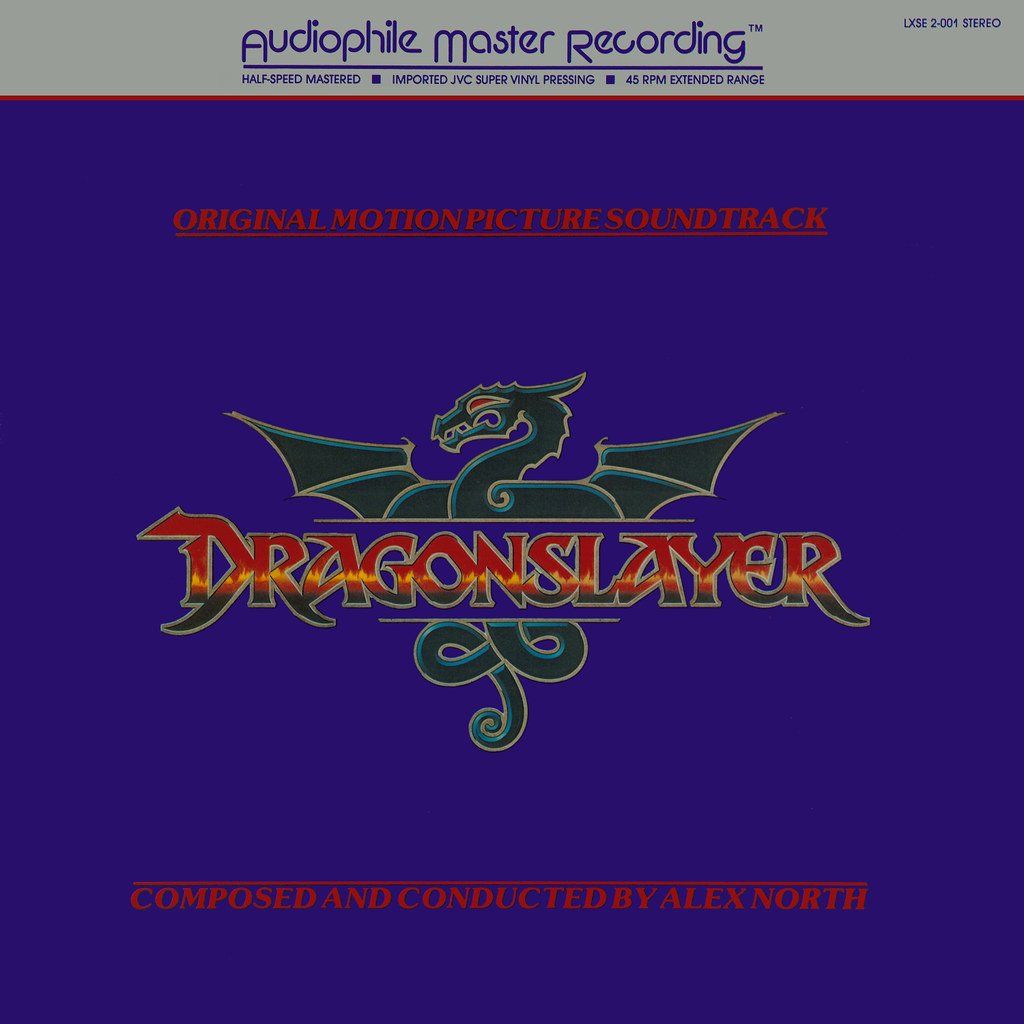

The following article was originally written to accompany the Label X [Southern Cross] Records release of Alex North’s DRAGONSLAYER soundtrack, now out of print. After the planned booklet did not materialize, this material was subsequently made available to CinemaScore by Mr. Rosar. While the article concerns specifically the musical cues appearing on the Label X recording, it should also be of interest as a more general analysis of this important film score.

The Story

During the Middle Ages, the country of Urland is besieged by a dragon – Vermithrax Pejorative, the last dragon on Earth. It has burned the Urlanders’ villages and scorched their crops black with the fire of its breath. Desperate in their plight, the Urlanders found that they could temporarily appease the dragon through human sacrifice. By lottery, a maiden was periodically chosen by the King from among the villagers and given over to the dragon where she would meet with a horrible death.

Protesting this barbaric practice, a group of Urlanders, led by a youth named Valerian (Caitlan Clarke), sought instead to put an end to Vermithrax the dragon. Believing that the dragon could be destroyed by magical means, they journey to the distant Castle Cragganmore, the abode of a sorcerer named Ulrich (Sir Ralph Richardson) – the last living sorcerer. By fateful coincidence, Ulrich foresees the Urlanders’ dire circumstances and mission in the waters of his own cauldron – a vision which also seems to foretell his own doom. Ulrich agrees to fight their dragon.

Tyrian (John Hallam), the Captain of Urland’s centurion has followed the small group of villagers to Castle Cragganmore, and skeptical of the powers of sorcerers, elects to put Ulrich to a test. Ulrich agrees willingly, allowing Tyrian to stab him in the chest, exclaiming that nothing Tyrian can do will harm him. But no sooner is the dagger in Ulrich’s breast than he falls to the ground, dead. Scoffing at the mockery of all this, Tyrian departs. Later, Ulrich’s servant, Hodge (Sydney Bromley) and Ulrich’s young apprentice, Galen (Peter MacNicol), sorrowfully burn Ulrich’s body on a funeral pyre. As the flames leap high into the air, the night sky is streaked with shooting stars, portending magic yet to come….

Taking Ulrich’s magic amulet and Hodge with him, Galen sets out to fulfill his master’s promise to slay the dragon. On the journey, Tyrian maliciously kills Hodge with bow and arrow. The dying Hodge tells Galen to dispose of Ulrich’s ashes in burning water. Galen also learns that Valerian, who has posed as a boy to escape the lottery, is really a lovely young girl. Before they reach Urland, yet another maiden is sacrificed to Vermithrax.

Once in Urland, Galen promptly puts the magic amulet to work and buries the dragon’s lair in a landslide. Soon word of this extraordinary feat reaches the King of Urland (Peter Eyre) and Galen is taken captive to the King’s castle. There Galen tries to display his magical powers, only for them to fail him. Annoyed by Galen’s meddling in his affairs, the King orders that he be locked in a dungeon and has the amulet taken from him.

While the villagers celebrate the apparent demise of the dragon, a priest, Jacopus, learns that magic has been used to bury the great winged beast in his lair. He denies the powers of magic and goes to the dragon’s lair intending to vanquish the beast through the Powers of the Cross. But this leads to disaster, and Jacopus is consumed in the dragon’s breath. Furious, the dragon flies off to terrorize the Urland countryside.

With the aid of the King’s daughter, Princess Elspeth (Chloe Salaman), Galen escapes and continues his mission to destroy Vermithrax, armed this time with a mighty sword. The King orders another lottery to choose a sacrificial maiden in a desperate effort to subdue the dragon’s lust for destruction. Unbeknownst to her father, Elspeth has learned that the lottery has always been fixed so that she would never be chosen. Out of moral duty, she sees to it that it is her name which will be chosen in the new lottery, making ammends for her father’s dishonesty.

Galen hastens to the dragon’s lair, only to encounter Tyrian. They engage in a swordfight, and Tyrian is impaled on the sword meant for the dragon. Galen frees Elspeth from the sacrificial stake, but the Princess, determined to make amends for her father’s wrong, enters the dragon’s lair. Galen reaches her too late, and finds her being devoured by three grotesque progeny of the dragon. Galen enters the flaming subterranean cave of the dragon, narrowly escapes being burned alive, and fiercely attacks Vermithrax with his sword. In spite of his heroic assault on the monster, Galen fails to mortally wound it and the dragon takes flight in a rage of pain and anger.

Valerian finds the exhausted Galen and as she tends his wounds, their romance grows. Galen remembers Hodge’s dying words that he throw Ulrich’s ashes into burning water and realizes this must mean the lake of fire in the dragon’s cave. Racing back to the sulphurous cavern, Galen hurls the ashes into the flaming water, causing it to boil and roar up assuming the form of Ulrich. The form becomes flesh and blood, and Ulrich rejoins the living – at least long enough to see that the dragon is annihilated.

Galen and Ulrich hurry off to the mountains, where the final confrontation between the sorcerer and the dragon takes place. Vermithrax swoops down and carries Ulrich off, who shouts to Galen to destroy the magic amulet. Hesitatingly, Galen obeys, and Ulrich and the dragon explode in midair in a great flash of light. The remains of the dragon crash to earth in a flaming heap, whereupon the King promptly assumes full credit for the creature’s destruction. The last dragon on Earth now slain by a heroic deed, the young lovers, Valerian and Galen, ride off into the sunset on the back of a white horse.

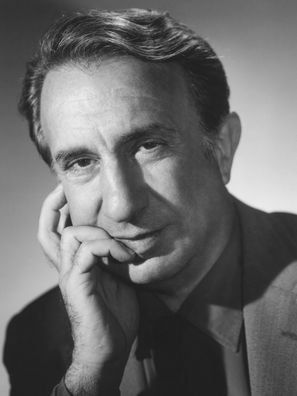

The Composer

Alex North was born in Chester, Pennsylvania, on December 10, 1910, of Russian parents. Pursuing musical studies from an early age, he studied piano with George Boyle in Philadelphia at the Curtis Institute of Music. At the age of 20, he went to New York where he studied at Julliard, supporting himself by working nights at Western Union. With this near-sleepless schedule, North’s health began to fail, and he searched for an alternative means of supporting his musical studies.

In 1948 North wrote the music for Elia Kazan’s New York stage production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. Kazan was so impressed that when he came to Hollywood to direct the film adaptation of A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE in 1950, he asked North to accompany him and score the picture. North’s jazz-oriented score was a milestone, and became the beginning of a long career in film composing which has proven to be one of the most distinguished in Hollywood. North’s scores have included VIVA ZAPATA!, THE ROSE TATTOO, THE RAINMAKER, THE BAD SEED, THE LONG HOT SUMMER, SPARTACUS, THE MISFITS, THE CHILDREN’S HOUR, CLEOPATRA, CHEYENNE AUTUMN, THE SHOES OF THE FISHERMAN, WILLARD, THE PASSOVER PLOT, CARNY and John Huston’s 1985 picture, PRIZZI’S HONOR.

The Music

North came to London in September, 1980, to view rushes of the DRAGONSLAYER film, and met with the executive producer, Howard Koch, as well as Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins, the co-authors and producer and director, respectively. Although at this meeting overall concepts were discussed, it wasn’t until February of 1981 that North was invited to San Anselmo to actually spot the music, determining where the music should go. North spotted the picture with Matthew Robbins present, who tape-recorded his comments and suggestions for what he wanted the music to be doing in certain sequences.

North welcomed this, because he believes that even if a director expresses his thoughts about music awkwardly, and in non-musical terms, it nonetheless gives him useful clues as to what the director wants in a score. North recalled: “Robbins and I saw eye-to-eye in our likes and dislikes in music. He gave me a book on Prokofiev because I was a big fan of Prokofiev as a kid. He allowed me to take my time in the recording, which I was very grateful for, not having somebody over my shoulder saying, ‘Let’s get on to the next piece now!’ The picture offered me any number of opportunities in a dramatic sense that had nothing to do with characters. Except for the boy-girl relationship, everything had to be so removed from myself, because very often I’m able to express some inner feelings about how I relate to the film. I achieved that approach with A MEMBER OF THE WEDDING and WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF, where you have interpersonal relationships which lend themselves to the kind of score which is not necessarily lyrical but has more soul….is more compassionate. There was very little compassion in this story. It was not one of those kinds of films where you get thematic ideas in advance, jot them down and re-work them later.”

As with other films set in historical periods such as THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY, SPARTACUS, CLEOPATRA and THE PASSOVER PLOT, where North often spent months researching authentic material of the period and locale, he sought with DRAGONSLAYER to capture the spirit, if not the letter, of Middle Ages music in his writing. Unfortunately, there was very little material for him to draw upon other than church music. Rather, he found that there were only pictures of what certain instruments looked like with little clue as to what they sounded like. Given this limitation, North tried to evoke the setting of the story by incorporating modal intervals and cadences in his melodic material, and by using harmonies built on fourths and fifths instead of thirds, suggestive of Gregorian chant.

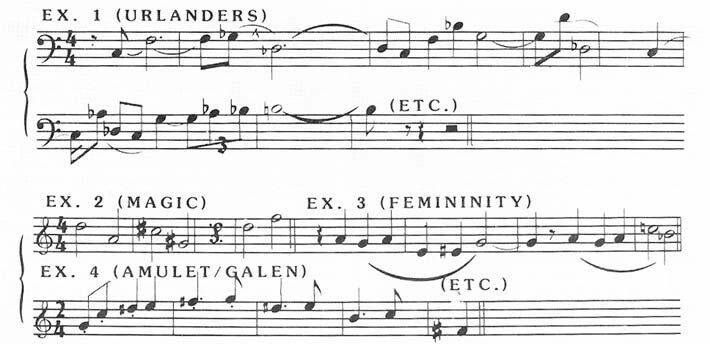

North’s score is based largely on five principal thematic ideas. In order of their first appearance in the score, there is a plaintive theme for the Urlanders, which attempts to capture their suffering and frustration, and is used as a musical motto heard in many different moods and guises throughout the score (musical example #1); a theme symbolizing magic (example #2); a theme for Ulrich’s magic amulet which later becomes associated with Galen (example #3); a theme evocative of femininity, associated with the sacrificial maidens (example #4); and a theme associated with the romance of Galen and Valerian (example #5).

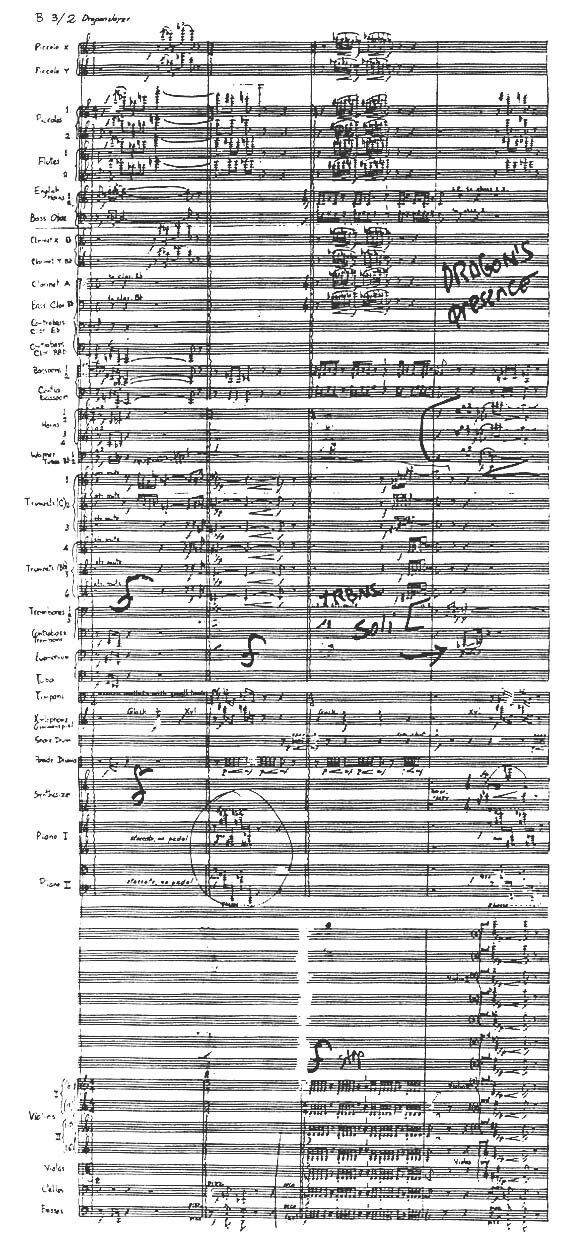

Although only a lengthy musicological treatise could do justice to the myriad compositional techniques and orchestral resources North employed,* a few of the most striking technical features should be mentioned before discussing the music within the context of the film. For example, the score is a veritable textbook in polyphonic writing, some of which is linear par excellence. The music in some places consists of as many as five layers at once, the textures remaining extraordinarily transparent throughout in spite of their complexity.

North used a large symphonic orchestra of 89 pieces, including a number of unusual instruments to achieve certain effects. He augmented the percussion section with three low log drums, two parade drums, clavitimbre, one tack piano, harpsichord, organ, bell tree, thunder sheet and wind machine – many of which he used both for eerie musical sounds related to the magical elements in the story as well as to emphasize the primeval and austere Urland countryside. Additional woodwinds consisted of six piccolos, two contrabass clarinets, baritone and bass oboe. These instruments, as well as euphonium, contrabass trombone and Wagner tubas, accentuated and gave greater clarity to the upper and lower ends of the orchestra. One of North’s purposes for this instrumentation was to emphasize the extreme bleakness and desolation of the brooding Urland landscapes.

The Recording

1 – Urlanders Mission

After a glowering passage in low brass establishing a primeval mood, a long poignant statement of the Urlander theme accompanies the film’s opening credits as we see the Urlanders making their way to Castle Cragganmore. As the scene changes to Ulrich in his castle, with his alchemical agents, we hear a motif associated with magic (example #2) before returning to the Urlander theme.

3 – Ulrich’s Death and Mourning

With Ulrich slain by Tyrian, a doleful mood begins, conveyed in the music by a simple chant-like figure repeated and varied in different orchestral colorings as Ulrich’s body is committed to the flames. As much as to say “farewell”, the orchestra swells into a scintillating flurry of sound embodying the awe of Ulrich’s funeral pyre being consumed in flames as the sky is filled with shooting stars. As Robbins wanted it: “Big, weird, dizzy – bursting out into motion.” (This last effect was achieved mainly with a progression of rapidly alternating triplets of unrelated triads set in the high register of the orchestra over a ground bass).

4 – Maiden’s Sacrifice

The Urlanders ritualistically bring the sacrificial maiden to the dragon’s lair in a horse-drawn carriage. In one of the most exciting and musically interesting sequences in the score, North employs the full resources of the orchestra in a spectacular display of his extraordinary imagination for orchestral color. A strident variation of the Urlander theme (mainly stated in muted brass and nasal woodwinds) as we see the grim procession making its way towards the dragon’s lair followed by a very expressive one – sympatico – harmonized in fourths and fifths, as the forlorn girl is dragged from the cart and manacled to the post. As the leader of the ceremony reads the formal declaration of the sacrifice and its purpose to appease the dragon, we hear the plaintive “maiden” theme. The ground shakes, and the members of the group flee. The Urlander theme is subjected to grotesque dissonant distortions while an agitated version of the maiden theme interjects as the girl frantically tries to free herself. Managing to wrench her hands loose, she attempts to escape but to no avail and is consumed in flame as the dragon roars.

5 – Forest Romp

This spirited jig, reminiscent of the style of Prokofiev, is a lively development of the Amulet theme, as Galen and Hodge set out to Urland to fight the dragon. Now in possession of Ulrich’s magic amulet, Galen is anxious to test its powers and does so by levitating an egg as he walks, and also by playing impish pranks on Hodge during the journey.

6 – Hodge’s Death

In a reflection of a pond, Galen sees a vision in which Hodge is assailed by Tyrian’s bow, and rushes off to find Hodge. Dying, Hodge gives Galen Ulrich’s ashes, instructing him to throw them into burning water. This sad moment is captured with music of great expressivity, including a beautiful passage for English horn and bassoons of a haunting modal character. Desolate, Galen and the Urlanders journey by boat to Urland, the bleak primeval landscape reflected in the stark pizzicato strings and percussive sonorities.

7 – Galen’s Search for the Amulet

With considerable good humor, North musically depicts Galen’s frenzied hunt for Ulrich’s elusive amulet before leaving Castle Cragganmore. First hinted at in various orchestral guises (including timpani), the impish amulet theme finally emerges carried by bassoons, then English horns and low strings, all the while punctuated by ingenious orchestral decoration. Finally, in a swell of orchestral contrary motion, the mischievous amulet is found.

8 – Vermithrax’s Lair and Landslide

Once in Urland, Galen heads straight for the dragon’s lair despite much protestation from Valerian. As Galen enters the cave, North provides an aural equivalent to the vaporous, Stygian cavern which Galen encounters. North uses a variety of atonal devices for this purpose, creating strange bending, wavering sounds in the orchestra (one of which included the flutes playing a quarter tone off pitch) amid snatches of the Urlander theme. Putting the amulet to its first real test, Galen creates a landslide around the walls of the ravine outside the dragon’s lair, burying its entrance under tons of rock. As Galen chants the spell to accomplish this, there is a triumphant statement of the amulet theme in counterpoint to a brief allusion to the “cosmic” tintinabulating ending of “Ulrich’s Death and Mourning.” This is followed by wildly transformed bits of the amulet theme as the landslide occurs.

9 – Valerian and Galen’s Romance

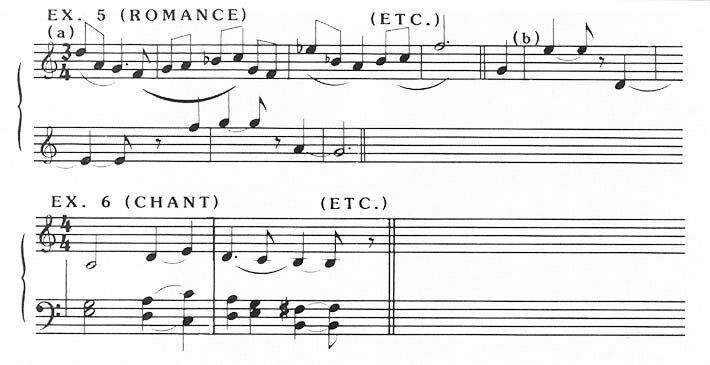

As Valerian and Galen’s love for one another blossoms, North captures the purity and poetry of youthful amour in a long lyrical melody with a modal flavor. In 3/4 meter, the theme is in two parts, the ballade-like first part (example #5-a) is introduced on clarinet with the strings joining in with simple accompaniment before being taken up by oboe. The second part of the theme, with its upward sweep, is waltz-like (example 5-b) and is actually alluded to fragmentarily in earlier sequences (In the film, this sequence actually occurs after Galen’s first battle with the dragon. The recording is not necessarily sequential in relation to the film).

10 – Tyrian and Galen fight

As Tyrian and Galen engage in a swordfight, we hear a very different treatment and development of the merry Amulet theme, which we now associate with Galen. What has hitherto been a light-hearted jig now becomes stark and ferocious, the subject of an elaborate polyphonic episode with virtuoso timpani playing. Interpolating are allusions to the Maiden theme, as Elspeth fulfills her destiny as a sacrificial victim, making her way into the dragon’s cave. The sequence concludes with a darkly victorious exclamation of the Amulet theme (much as we have known it earlier) as Tyrian falls dead from Galen’s sword.

11 – Jacopus Blasted

The priest, Jacopus, makes his way to the dragon’s lair intent on vanquishing the beast with the Powers of the Cross. For this, North used a 6th Century Gregorian chant (example 6), developed into a set piece which stands alone musically as an integral whole. With ingenious woodwind and brass writing, North convincingly evokes an organ-like sound without actually using an organ. The chant unfolds into even grander proportions as the priest’s exhortations become more fanatical with the very ground beneath him trembling and finally rupturing. Shaken to the ground, the priest clambors to his feet and, accompanied by grotesque brass clusters that clash against the chant, Jacopus is incinerated in a blast of flame from the dragon’s mouth.

12 – Elspeth’s Destiny and Dragon’s Scales

We hear a poignant statement of the Maiden theme as Princess Elspeth seeks to right her father’s wrong by fixing the lottery so that she will be chosen as the next sacrificial maiden. With a reprise of the “Lair” music, Valerian removes scales from the dragon’s cave to make a fire-proof shield for Galen, only to discover that the dragon has given birth to three small, hideous offspring, which try to attack her.

13 – Galen Jailed and Escape

As Galen is jailed and the amulet taken from him, North provides an allusion to the Urlander theme as it was heard during the “Maiden’s sacrifice” procession. Aided by Princess Elspeth, Galen stages a gallant escape on horseback to the accompaniment of the Magic and Amulet themes. A lively reprise of the Amulet theme as heard in “Forest Romp” is augmented with fragments of the Romance theme (example 5-b) used cleverly as a horn figure.

14 – Dragon’s Flight and Burning Villages

Having flown off in a fury, the dragon wages havoc in the villages of Urland, scourging their crops with its fiery breath as it soars across the countryside. In a musical montage reflecting furious action with scenes contrasting catastrophe with pastoral romance, we hear brief snatches of the emerging Romance theme (5-b) intermingled with chaotic phrases of the Urlander theme.

15 – The Lottery

In the moment of truth, when against his will the King must choose his own daughter for sacrifice, the music presents us with fateful chimes and the Maiden theme given an unusual variation, using tone clusters in the strings to suggest the sound of wailing female voices. At one point, we hear the Maiden and Urlander themes contrapuntally.

16 – Elspeth at the Stake; Vermithrax Triumph; Galen’s Encounter

The Maiden theme once more sounds forth mournfully in counterpoint to the Urlander theme, as Elspeth is taken in procession to the dragon’s lair. Galen freed, he dispatches Tyrian (“Galen and Tyrian fight”) and with his shield of dragon scales enters the dragon’s cave. There he finds that Elspeth has met her end at the hungry mouths of the dragon’s progeny. Galen slays all three of them with his sword. Avoiding the blasts of fire from the dragon’s mouth, Galen attacks the monster, the thrusts of his sword caught musically with percussive clashes in the orchestra. The Urlander, Magic and Galen themes all come into play in a sequence of orchestral bravura which includes an extended reprise of the glowering low brass passage that opened the picture. This gives way to a contrapuntal tour de force based on the Urlander theme as the battle ensues, Galen failing in his valiant efforts to slay it.

In an earlier sequence in the film, Galen despondently reviews the path he is following, as seen in a vision in a pool of water (“Galen’s Encounter”) – images of Ulrich (musically suggested by a reference to the chant-like motif of “Ulrich’s Death and Mourning”), and then of Hodge’s peril and death. This is musically contrasted with a jaunty recapitulation of the Amulet theme with its youthful exuberance, reflecting Galen’s revitalized spirit.

17 – Eclipse; Love and Hope

An eclipse of the sun, a terrifyingly magical event to people of the Middle Ages, is atmospherically captured in an impressionistic interlude of delicate orchestral latticework. This is followed by the Amulet theme played on harpsichord with an undulating ostinato accompaniment as the restless Galen ponders his defeat in battle against the dragon, and what course of action to take next. Elsewhere, another priest urges prayer as an answer to the Urlander’s strife, as suggested by a brief reprise of the chant motif heard in “Jacopus Blasted.” A beautiful, noble statement of the Urlander theme from woodwinds seems to bespeak the heroic deed remaining to be done, which the salvation of Urland depends upon. From his growing love for Valerian, portrayed in a rapturous variation of their Romance theme (with no less that five different lines in the strings!), Galen derives inspiration.

18 – Resurrection of Ulrich

In a vision, Galen sees the lake of fire Hodge spoke of, and realizes what he must do. With Ulrich’s ashes, he returns to the dragon’s cave and scatters them into the burning lake where the dragon lives. In one of the film’s most dramatic sequences, both visually and musically, Ulrich is reborn from the flaming water and resumes mortal form. A magnificent recapitulation of “Ulrich’s Death and Mourning” is heard as the sorcerer rejoins the world of the living.

19 – “Destroy that Amulet!”; Ulrich Explodes; Vermithrax’s Plunge

Ulrich tells Galen that his presence on Earth is only temporary to insure the destruction of the dragon. A sense of urgency characterizes the music, as Ulrich explains to Galen the magic involved for the final act. We hear a synthesis of the unearthly music of “No Sorcerers, No Dragons!” juxtaposed with the “cosmic” ending of “Ulrich’s Death and Mourning”. Ulrich, Galen and Valerian go to a nearby mountaintop, where Ulrich tells Galen to destroy the amulet. galen does so, and in so doing destroys both Ulrich and the dragon. In the wake of this spectacle, the romance of Galen and Valerian blossoms in a rich tapestry of strings and woodwinds.

20 – The White Horse; Into the Sunset

The dragon destroyed, for which the King immediately assumes full credit, the two young lovers ride off into the sunset on a white horse which seems to magically appear just as they wish for it. As the musical finale and end title sequence, North draws together all his themes with an air of resolution and tranquility at the happy ending.

Thank you, Alex North, for another masterpiece which all film music devotees will long enjoy and cherish for years to come.