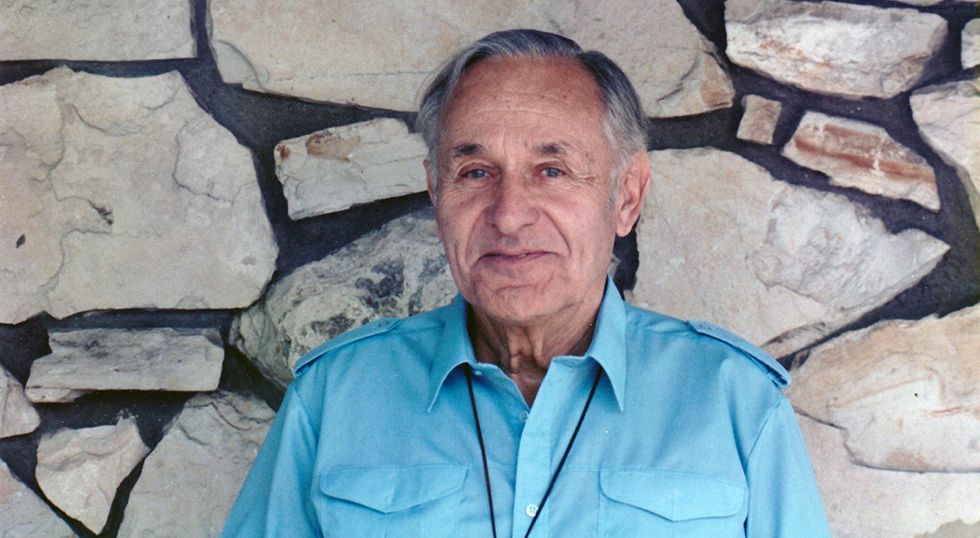

An Interview with Russell Garcia

A Conversation with Russell Garcia by Matthias Büdinger

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.11/No.44/1992

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

Let’s start from the very beginning. Where were you born?

I was born in Oakland, California. That’s the San Francisco Bay area. I studied music at the San Francisco State University, classical and symphonic composition all the time. I went on the road with big bands for about 3 years – that was the era of the big bands. I was writing music and I used to play trumpet. However I decided that I wasn’t earning or progressing. So I went to Hollywood and studied with the first teachers I could find there. I learnt a lot more that way. Edmund Moross was a known teacher, Ernst Toch, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and…

All of them immigrants…

Yes, and I studied conducting privately with Sir Albert Coates. It was a wonderful opportunity because we had a rehearsal orchestra every Wednesday afternoon. The studio musicians sometimes just liked to come and play the symphonic repertoire after always playing studio music. So I got to conduct a tone poem and a movement from a symphony – every week for a couple years, which gave me great conducting experience. In fact Stravinsky brought his Circus Book to us and we played it for him, the first time he ever heard it. He lived up in the Hollywood hills and had a great sense of humor. I’ve been fortunate meeting a few famous composers, for instance Shostakovich. I had a 3-hour lunch with him. He was a wonderful man. If you want to read an interesting book, read his autobiography, which wasn’t to be published until after he was gone.

He passed away in 1975 I think.

Has it been that long? He made a wonderful statement. He said to me, “We get along so wonderfully on a personal level. It’s a shame the countries in the world don’t get along as well as little children. They could solve their problems.”

You mentioned Stravinsky’s sense of humor. Can you recall any particular event?

We were recording some Stockhausen music in a studio in Hollywood. The tuba player – it was an upright tuba – had to put a big mute in, about 2 or 3 feet long. But he had only a couple of bars to put the mute in and out. To do it himself he would have to put the tuba down and he couldn’t do it in two bars. So Arthur Morton, who is also a composer from way back, stood on a chair behind the tuba, reading the music. He put the mute in and out at the proper times. Stravinsky and I were in the recording booth. He put a dollar bill down there and he said to Arthur Morton, “75 cents for putting mute in and 25 cents for putting mute out.”

You have taught seminars at universities…

Yes. Sam Spence was actually a student of mine when he was a young boy. I had a lot of people who came to me because they got the ivory-tower type of music at university. They would write tone-row string quartets and all these wonderful things, but to work in the music business you have to use all these devices and you have to know how to use them in practice. So a lot of people came to me for a quick course and we went through everything they had learned. But I just showed them the practical application of it.

Did you teach film music as well?

No, what I taught was every type of music n composition, techniques, harmony, counterpoint, all these things, but in a more practical and modern way… They’ve always taught harmony here starting way back in the 16th, 17th century or whatever, and then they taught counterpoint separately. I can’t separate them. These things have to be taught together. I wrote two books on writing music, and they’ve been selling very, very well all over the world. One book is in five languages and it’s everywhere. I met music writers in Russia and even they had it. The books are actually used in universities around the world. Quincy Jones once wrote in my book, “When Russ takes the time to share his knowledge with you, you better listen.”

Were there any prominent film composers who came to your courses?

Of course. Johnny Williams was a student of mine and when Quincy Jones did his first two film scores I worked with him all through them because he hadn’t had any film experience. I even did parts of the composing.

But you didn’t get any credit?

No, I didn’t. I’ve done a tremendous amount of work without credit. I worked with Universal Studios steadily for over 15 years, just working all the time. I didn’t often get credit but on some films I would.

What was it like working more or less in the shadows? That must have been awful.

Well, I got very well paid.

Ah, that changes everything. Very often the men behind the scenes are the ones who do everything, whereas only the “big” names in the foreground get the credit.

Occasionally. My first job at Universal Studios was THE GLENN MILLER STORY. Henry Mancini wasn’t doing it. Glenn Miller’s widow had most of the arrangements they needed, the original Miller ones. There were 3 or 4 numbers they wanted to use in the film, but they didn’t know where the music was. So they asked Hank Mancini, “Who can take these off of the record, note for note, exactly like they are?” Hank said, “Call Russ”. I worked with him on that film and a couple of other pictures. If Universal wasn’t too busy at any time I would work for Disney, MGM, Fox or whoever happened to need my services.

But you never had a contract with MGM?

I always free-lance. If I did a TV series at any studio, I’d have a contract for that series. If I did a feature film I’d sign a contract specifically for that film. But you have an agent who does that. The agent never got me any work. I have to get work myself, but the agent can talk money for it. He gets me three times as much as I could. Composers don’t like to talk money or be involved in the business.

Back to your Universal days. You must have met every composer we can think of. You just mentioned Henry Mancini who worked there for six years…

We’re still very close friends. We have dinner often when I go to Hollywood. He is a wonderful person as well as a very talented composer.

I think he is one of a handful of composers who is gifted with melody.

That’s true. Well, a lot of the old film composers aren’t doing so much anymore.

But Mancini is still very busy.

Always. But the film business now is in the hands of young people. Charles Walker and I went together to Hugo Friedhofer’s funeral in Westward, California. All the film composers from our era were there and David Raksin gave a little talk about Hugo. He said, “All of us here are from the era where film composers could read music.” He got a big laugh for it, because nowadays they bring in a lot of inexperienced kids with guitars and such. An awful lot of scores are done with one person and all of the machines, emulators and such that imitate instruments. They can save a lot of money on a score if they don’t have to hire live musicians. A lot of recordings are being done in Europe because it’s expensive in Hollywood. The Unions got prices so high. A lot of composers even go to Bulgaria.

And Jerry Goldsmith himself went to Hungary for HOOSIERS, for instance.

They raised a big fuss because people wanted to give him an Academy Award, but the Unions were screaming because the music was recorded in a communist country.

Jerry Goldsmith went back to the roots of Miklos Rozsa, so to speak. What about Joe Gershenson and Frank Skinner? They worked for Universal as well.

Joe was the music director for feature films.

He was the one who always got the credits.

Yes, for he did a lot of conducting. We would compose the score. On films sometimes I do the composing, sometimes composing and arranging, sometimes the conducting. For TV I did all my own conducting, but Joe Gershenson wanted to conduct almost every feature film. One day I decided to go away with our sailboat and to sail across the Pacific Ocean, just leaving all of this. Joe Gershenson called me the day before I left and said, “Come in, I want you to see and do a feature film, Russ.” I said, “Joe, I told you, I’m going on my sailing trip.” He said, “Oh, put it off for 6 weeks. Do the film.” I replied that if I put it off for this I’ll put it off for something else and pretty soon my health won’t be good enough and I maybe too old to take a sailing trip.

What kind of man was Frank Skinner?

We were very good friends. I worked with Frank a lot, especially when I first went to Universal. If he had a film to compose he would make a sketch and then I would do the arranging. He was very talented. He always wrote very simple, clean, pure music and it always fit the film beautifully.

You also worked with Henry Mancini on TOUCH OF EVIL…

That’s true. Hank got a big check when they sold the rights for that film to TV. He sent me a good part of it. That was very nice of him. He could have just kept it and I would never have known the difference.

You must have been befriended by all the composers in Hollywood. Do you remember any funny episodes with some of them?

Very often a producer or director from Universal Studios would go back to New York. They would have a few drinks and perhaps be in a nice restaurant or bar in New York City. They would hear some pianist who may have written a nice tune. They’d say, “Oh, beautiful. We want you to score our next picture.” Of course this pianist would have no idea about setting music to film, with the timings and the moods. They have no idea how to orchestrate. So they would hire them and Joe Gershenson would call me and say, “Russ, they’ve done it again.” I’d come in and I’d have to take their themes. Even for persons like Bobby Darin, I did 2 films for him. He thought he wrote the scores because he gave me a two-bar little phrase and another eight-bar phrase. That’s what he made up and I wrote the whole film score. But I would be paid very well for these types of things. So it’s all right. I’m not in this business really for money, but…

… but you need it.

Yeah, money is not everything. It just buys everything.

“Money Makes the World Go Round,” as it is sung in CABARET. What’s your impression of the contemporary film music scene when you come from the “Golden Age” of Hollywood film music?

Some of it’s good and some of it’s just terrible. I even like some of the pop music, but some of it is so amateurish and so monotonous that I don’t like it at all. I don’t go to too many movies. I very carefully pick the ones I want to see because I get headaches from screaming pop music going all through a film.

Are there any contemporary film composers you like?

Well, Jerry Goldsmith writes some very nice things. But most of the music is done in a pop idiom now.

That sells better than symphonic film scores. It’s more exploitable.

I suppose. A lot of the 12-year-old kids go to the movies and they attract them with this type of music.

Working steadily against deadlines, was that a problem for you?

I never missed a deadline in my life. I can write very quickly. I was forever helping other people who couldn’t make the deadline. Every once in a while I got a phone call at midnight from Billy May, Johnny Mandel or whoever saying, “Russ, I got a recording session at nine in the morning. I’m not gonna make it. Can you help me out?” So maybe I’d stay up all night and write a few arrangements. Disney’s would only call me when they were in trouble with the deadline. The orchestra was coming in the next day or the day after and they weren’t going to make it, because Disney always kept all their composers and arrangers on a weekly salary and they didn’t have to pay them very much. But they had to pay me so much a page. So it cost them a lot more when they had to use me, but they knew I could work fast and well. So if they were in trouble they would call me and I worked over there if I wasn’t busy at Universal. Usually at Universal I had to write 30 or 40 minutes of music for a big orchestra each week. I had the Universal Orchestra almost every Friday afternoon right after lunch for as long as I needed to finish it.

I think one of your greatest gifts is versatility. You can write in any style.

Well, at Universal one week it was a big love story with strings, the next week it would be a detective story with jazz, the next week a science-fiction film and who-knows-what. Because of my name being Garcia, in the beginning a lot of studios would call me for big Latin productions. They thought I must be an expert in this but I’m no more Spanish or Mexican than you are.

You are no longer in the film business, are you?

I work here and there, but not a tremendous amount, because I live in New Zealand and I’m there 5 or 6 months a year.

The rest of the year you spend in Hollywood?

Well, wherever there’s work for me. I work in New Zealand. I conduct pop symphony concerts and I do radio shows with orchestra and choir, whatever they want and need. Sometimes I work in California. Pop singers make their tracks for their guitars, bass, keyboards, drums and their voices. Then they want strings, French horns, flutes or whatever. They call me and give me a cassette of what they’ve done. Most of them don’t read a note of music. I listen to what they’ve done and then I write string parts. Occasionally, if I’m in Hollywood and somebody needs something for a film and they know I’m there, they call me. For instance, two years ago they had a very brutal thing in a Sofia Loren film. They decided they wanted music coming out of a hifi set in this apartment instead of scoring the brutality. They wanted “just source music”. They called me and told me they wanted something in a Glenn Miller – Benny Goodman – Tommy Dorsey style, because the film was set in the forties. So I did 3 or 4 pieces in that style. I do little jobs like that. But you have to be in Hollywood all the time to be working. I left that. I write a lot of symphonic music now and I do albums in the jazz field quite often.

You just mentioned your symphonic works…

Oh yes. It’s like Miklos Rozsa. I don’t think he does too much film work any more, does he? He would like to become known more as a symphonic composer, which he does quite well. I guess we would all like to get into that field, I’ve written many symphonies.

Are there albums with your symphonic works?

Not really. I recorded a lot for radio but there are a few things on recordings of classical compositions. I did ‘Theme and Variations for Ten French Horns’. That’s recorded on Capitol Records. I got tapes of compositions with the Hamburg Radio Orchestra and orchestras in New Zealand of course, but no big albums. I did a couple of films in Berlin, for instance a Francis Durbridge “Krimi” called NULL UHR ZWÖLF (12 MINUTES AFTER MIDNIGHT). I recorded that in Berlin many years ago. Then I did some short things in German films. I also worked in Vienna. They used to give me a symphony orchestra together with a big band. I used to do big productions for the Austrian Broadcasting Station.

Your career has included arranging and conducting with Judy Garland, Andy Williams, Oscar Peterson, Ella Fitzgerald and many others, no important names are left out…

The list goes on and on, Sammy Davis, Mel Torme, everybody. I acted as their arranger and conductor for record albums.

And concerts as well?

Yes, some of them. I conducted Louis Armstrong at the Hollywood Bowl. He had his little jazz group and we had the Hollywood Bowl Symphony which is the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Wasn’t Henry Mancini’s wife one of Mel Torme’s singers?

Yes, she also worked for me. Recently she said that she met me before she met Henry.

So you could have been Henry Mancini. That’s the same story Henry once told when he met Blake Edwards; he came out of a barber shop. Hank wondered if Nelson Riddle had come out…

We’re recalling the old days. A lot of us in Hollywood had these little offices in this big old building – a big cement building that used to be the first film studio in Hollywood. These were all dressing-rooms but then the studio grew all around it. In all these dressing-rooms we had offices. Nelson Riddle had one. Dick Hazard and a lot of the writers. Nelson was starving then. We’d go buy a loaf of bread and a jar of peanut butter and have to eat this for a couple of days.

Yes, another one who could have lived much longer. And someone like Irving Berlin got 99 years old! Did you know him?

I met him once. We did a show of his in Los Angeles. I did all the orchestration and arranging on this show. They needed a ballet sequence and had me write the ballet. When Irving Berlin came up a week or so before the show, he said, “I never heard of this guy. You can’t have somebody write a ballet in a show of mine.” They played it for him and he loved it. That’s the only time I’ve met him.

Do you know Leo Arnaud? The ‘Composer Arranger Society’ had a dinner honoring him. He was very talented and did an awful lot of ghost-writing, like I did. In fact there are a few well-known composers that would have been nothing if he hadn’t been behind them. He was a so-called arranger, but he went on doing more composing.

Like yourself. It’s a shame you didn’t get credit. What do you think of the film business now?

Films are such a great media. They can be so artistic, so wonderful. But they put out so much junk now. It’s a shame. You really have to search for the good ones now. I get to busy that most of the films we see are on airplanes. Once in a while we go to a movie.

With special thanks to Joanna Jenkins and Monica Barber.