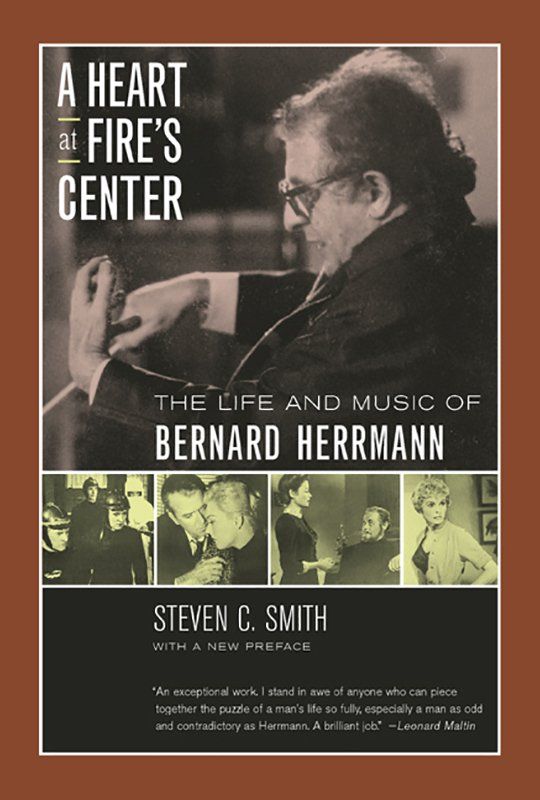

A Heart at Fire’s Center

A Heart at Fire’s Center

Author: Steven C. Smith

Publisher: Berkeley & Los Angeles : California University Press, 1991, 2002

No composer contributed more to film than Bernard Herrmann, who in over 40 scores enriched the work of such directors as Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, François Truffaut, and Martin Scorsese. In this first major biography of the composer, Steven C. Smith explores the interrelationships between Herrmann's music and his turbulent personal life, using much previously unpublished information to illustrate Herrmann's often outrageous behavior.

Steven Smith deserves the highest praise for having written such an absorbing biography of Bernard Herrmann – the screen’s foremost musical dramatist. The work which has gone into this book is formidable. Meticulously researched (Smith has had access to Herrmann’s letters and papers, whilst every quote is given acknowledgment as to its source) it presents a fascinating portrait of the composer. Although the book touches on his private life, it is essentially Herrmann’s professional life which interests the author.

Too many recent books about film music have concentrated on analysing specific scores. Smith keeps analysis to a minimum and concentrates on giving us a wealth of anecdotes and details of Herrmann’s working habits from those who knew and/or worked with him.

What the book illustrates above all else is Herrmann’s cantankerous personality: his remarkable propensity for arguing with all and sundry, be it a studio executive or a cab driver. Page after page details his irascibility, his falling out with colleagues and friends, his inability to meet people without aggressively disagreeing with them about something. Yet the book’s title is apt for Herrmann was a man of contradictions. Many people bear testimony to his kindness and warmth. His letters certainly show that beneath the gruff exterior was someone of great sensitivity.

His film scores tended to reflect the volatile side of his personality. His fondness for low brooding notes and a keen sense of what sounds could strike tenor in an audience. But the obverse side of his nature brought forth such romantic scores as THE GHOST AND MRS. MUIR and VERTIGO.

Alfred Hitchcock’s disagreement with Herrmann over TORN CURTAIN is given considerable attention. Herrmann obviously deeply regretted the break-up but why Hitchcock, in particular, took the attitude he did in dismissing his composer from the film remains obscure. Certainly a series of letters between the two prior to the start of the film shed some light, in that Hitchcock was perhaps intimidated by Herrmann. Unfortunately the director never made any public comment on the matter.

Ultimately the picture of Bernard Herrmann which emerges after reading this book is of a rather frustrated man who could never find contentment. His constant anger and dissatisfaction certainly contributed to his early death. Many lesser composers have tried copy Herrmann’s style and the word Herrmannesque has become a cliché – but none have succeeded in coming close to the unique talent that he possessed and whose music enriched so many films.

Doug Raynes – Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.10/No.40/1991