Philip Sainton comes of a family well-known in English music for the past hundred years. He himself has had a distinguished career as a performer and composer. He was born in Arques-la-Bataille, in Seine-Maritime, France, grandson to violinist Prosper Sainton and contralto Charlotte Helen Sainton-Dolby. He started his music studies learning the violin. At some point he entered the Royal Academy of Music in London, where he studied composition under Frederick Corder and viola under Lionel Tertis. Shortly after World War I, he joined the Queen’s Hall orchestra, which he relinquished in 1929 to replace H. Waldo Warner in the London Quartet. In 1925 he was also appointed principal viola of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1930, after the London Quartet’s tour of the United States, he joined the BBC Symphony Orchestra. His composition activities had begun early. Already by 1923 he had conducted his first orchestral work, ‘Sea Pictures’, at Queen’s Hall promenade concerts. In 1935, Sir Henry Wood conducted the premiere of his Serenade Fantastique with Bernard Shore playing the viola. His other works have been performed under the direction of Sir Adrian Boult, Sir John Barbirolli, the late Leslie Heward and other conductors. ‘Two Sea Pictures’, ‘Nadir’, ‘The Island’, ‘Serenade Fantastique’, the ballet ‘Dream of a Marionette’ are among his compositions that have been widely heard in the concert hall and on the air. Today, he is perhaps most remembered as the composer of the score for John Huston’s 1956 film Moby Dick. He died 1967 in Petersfield, Hampshire in England.

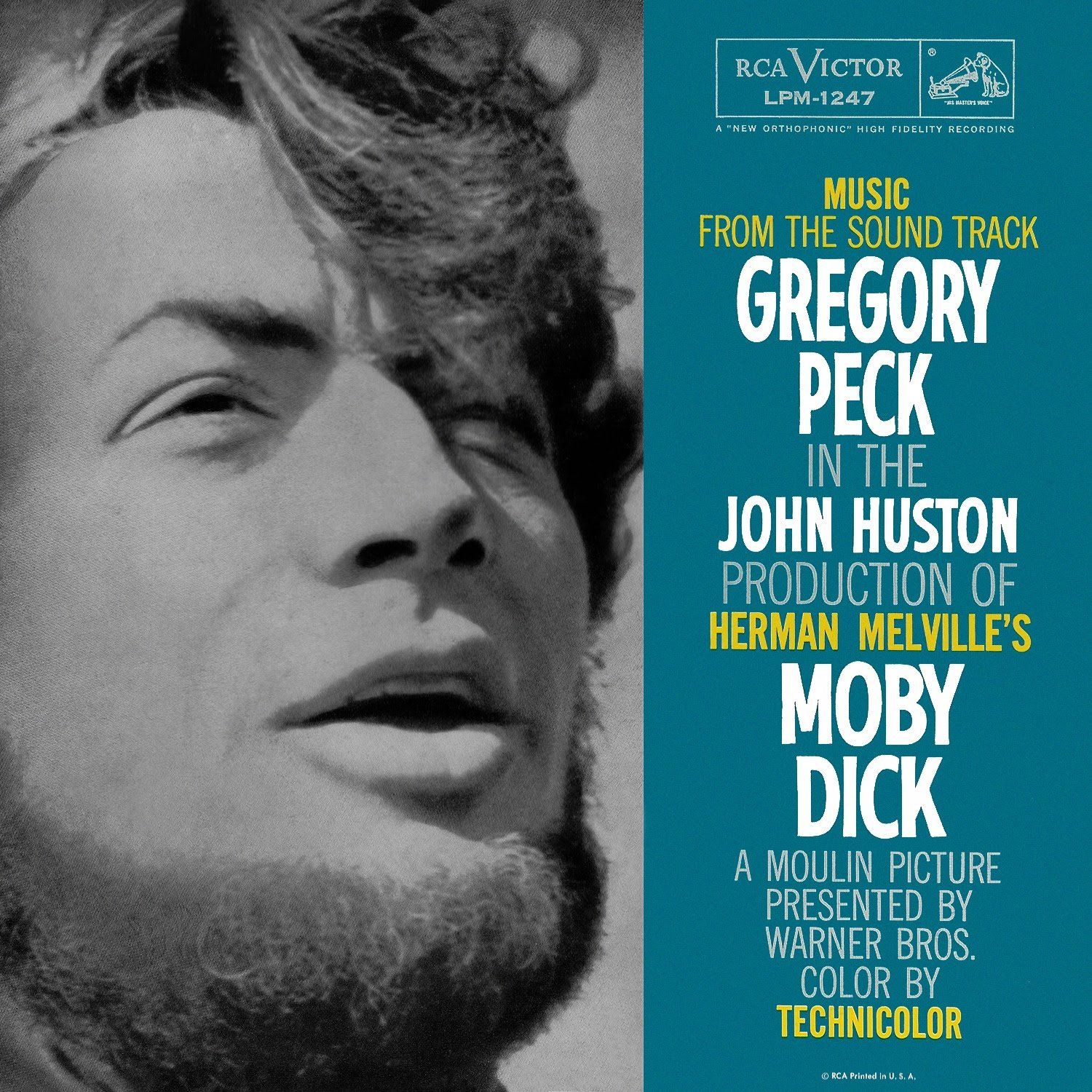

Moby Dick

I have been composing music for the greater part of a lifetime, and although I must confess to having entertained secret hopes that someone would some day ask me to do the score for a film, I had never really expected that it would happen. The music chosen to accompany the vast majority of film is not the sort of music that I find congenial to write. I knew, too, of fellow-composers who had been forced by film companies to work within time-limits that I should have found intolerably constricting. A piece of music that takes a minute to play takes a day to write and orchestrate for full orchestra – that is what it takes me, at any rate – and so I was never really sanguine enough to hope that the day would come when a director would not only request of me the sort of music I love but would also leave me, within reasonable limits, free to write it at my own pace and in my, own time.

It is strange the way things happen. Although my works have received respectful attention in musical circles, it was almost by accident – certainly not through any composition of my own – that I was unexpectedly enabled to achieve my private ambition to write the score for a film. It came about in this way.

For some twenty years I have enjoyed the friendship of Jack Gerber, a steel manufacturer of Lowmoor. His two hobbies, as dissimilar as you could find, are horseracing and music. He is an amateur composer, and from time to time he commissions me to score and arrange his more ambitious works. A short while ago I orchestrated two of his compositions, ‘Fiesta’ and ‘Stonehenge’, and then I assembled an orchestra of sixty players and in a single session I conducted them in a recording of both works for HMV. John Huston happened to hear ‘Fiesta’, and he was sufficiently interested in it to ask if he might meet me. He was then looking for someone to write the score for MOBY DICK. That was in Ascot week in 1954.

At our first meeting he asked me to set to music Melville’s ‘hymn’, ‘The ribs and terrors in the whale’. In a day or two I wrote the original tune that is sung in the chapel scene. It is of a type that might well have been sung by fisher folk a hundred years ago. Leslie Woodgate recorded it for me, and it was sent to John Huston in Ireland. It was on this slender evidence that Huston later commissioned me to write the whole orchestral score.

Since those days many people have said to me that they supposed, since the score breathes the passion and excitement of the book, that I must have been a lover of Moby Dick since childhood. They are amazed – just as Huston was at our first interview – when I tell them that I had never even read it, indeed had scarcely heard of it. Huston actually gave me a copy of the novel to read at the same time as he handed me the script that had been prepared for the film.

If the score that I subsequently wrote is deemed a success, I want to underline the two factors that made it so. The first is that John Huston has a great understanding of music, and knows exactly the kind of sound he wants for each sequence in his films. He told me that I must treat MOBY DICK just as if I were writing an opera. There were no words that I better wanted to hear. This treatment ideally suited my own inclinations, and in his view it ideally suited the book as well.

So I happily followed his instructions, and that is why there is not one theme that keeps recurring, but several themes. In some sequences Huston wanted me to intensify in sound the visual scene; in others he required the music to reflect the thoughts and feelings of the characters. For instance, in the first hunting sequence he told me to write music that would be alive with the rest of the chase. The excitement of the crew was to be transmitted in sound. Then, when the Pequod comes upon an enormous school of whales, and thus from the crew’s point of view the voyage has attained its object, he asked for “carnival music” that would echo their exultation. I built this theme round old French hunting-calls, using mainly the open notes of the French horn. Again, Huston always spoke of the scene in which Ahab addresses his crew as Ahab’s aria, thus emphasising for me his wish that the dialogue should be musically treated as if it were being sung. For this sequence, which is also to be heard in the title music, I tried to create the illusion of an incessant hammering, to convey Ahab’s overwhelming obsession about Moby Dick.

It will be readily understood how helpful it was for me – for I had no previous experience of film-making – to be thus guided by a director who knew so clearly what he wanted. Although he has no technical knowledge of music, Huston is urgently aware of the effects which music can create; and having indicated what he required me to do, he left me to do it, un-plagued by interference. And that was the second factor that enabled me to give of the best of which I was capable. He made no unreasonable demands in the way of a rigid time-schedule; I was able to write at my leisure.

In November 1954 I went to Elstree at Huston’s request to see the film in the making on the studio floor, and then from January to April last year I concentrated on the script and leisurely wrote the themes I thought would be required. There were six of them, all quite short. Two I have already mentioned, the whale-hunting and Ahab’s aria. For Moby Dick’s own theme I tried to convey in music the relentlessness of the brute, its unappeasable thirst for destruction. On the other hand, for the Pequod’s departure I wrote some soft music that I hoped would be indicative of the crew’s silent dedication to their task.

The sea music I decided should not be divorced from the whole orchestration of the score. Thus there is no specific “sea” tune. The breadth and depth and silent enmity of the sea pervade the whole of Melville’s novel, and I have attempted to reproduce this through the music, showing its subtle influence on all who lived within its power. In this I was mindful of Huston’s advice that in certain sequences the sound should communicate what was passing through the minds of men.

Finally, there is the cataclysmic music at the end. Here I entwined the opposing themes of Moby Dick and Ahab and so fashioned a theme that should be heard throughout the dreadful scene in which all but one of the Pequod’s crew are killed. Then it changes to what I can only call the cataclysmic funereal music that plays while the monster slowly encircles the doomed ship. The rhythm here is subdued, for I was anxious that this music should not sound triumphant. What at last the Pequod sinks, we come to the climax of the film, and I have expressed it through a complete silence, a silence that last for four seconds. And then the coffin bobs up to the surface, and Ishmael, the only survivor of the crew, climbs on it and is rescued by the Rachel.

I worked on these themes for four months, rising each day with the sun in the lovely Surrey town of Haslemere, across the hill from Blackdown where Tennyson used to walk the woodlands and declaim his poetry. When the tunes were done, I reduced them to be played by a septet led by Jean Pougnet – five strings, piano and clarinet – and had them recorded. The records I took to Huston in Ireland, and he said he was delighted with what I had done.

Looking back on it, I see that my biggest problem was how to write music that would really enhance the visual scene and make its presence felt by every member of an audience, musical or not. I decided that the answer was rhythm. If there were a strong rhythmic interest, the music would hold the audience, for even the tone-deaf, heedless of melody, can recognize rhythm and respond to its insistence. I therefore concentrated on writing rhythmically grammatical sentences of music to fit the timings precisely, so that, however long or short the periods might be, the music should come, as it were, to a logically-placed comma or full-stop. Only where the Pequod lies becalmed in the heat have I not done this, because throughout this seven-minute sequence the music must bring to everyone a feeling of maddening monotony. For this scene Huston said he wanted “desert music”, reflecting the perpetual relentless heat and the sameness of the land.

I received the first sheets of timings at the end of May, and those well versed in the writing of film music will smile when I confess that as I looked at the pages of timings for Ahab’s aria, I gasped with fright. The sequence lasts for a little over six minutes, and for every 20 seconds – often for every 10 seconds – the footage was given. I had to accompany the dialogue as if it were being sung, and with the mood continually changing. I very soon discarded the metronome and stop-watch and solved the timings by elementary arithmetic, the sum being, “How many beats are wanted to cover 19 seconds if the tempo is 144 beats, to the minute.” Here I should like to say that I was greatly assisted by Louis Levy, director of music for Associated British Pictures at Elstree, who gave me a record of the dialogue. He conducted the whole score, and I am sincerely indebted to him for the able way in which he directed and fitted the music, as well as for the skilled advice he so freely gave me during the months we worked together. I hope that American audiences will recognize the superlative quality of the orchestra, which was composed of London’s finest players. The music is often very difficult, but it does not sound difficult the way this orchestra played it.

The recording sessions generally lasted for six or seven hours, and they continued from July until December. Progress was often slow, because sequences were more than once recut and I had to rewrite the music. At these recordings Huston was represented by Russell Lloyd, who earned my thanks and immense admiration for his skilful balancing of the music with the sound effects. Here again I was lucky, in working with an editor whose deep appreciation of music was matched by his technical knowledge. Writing this score was a tremendous, and sometimes frightening, experience for one whose previous work has been done in calmer and less momentous circumstances

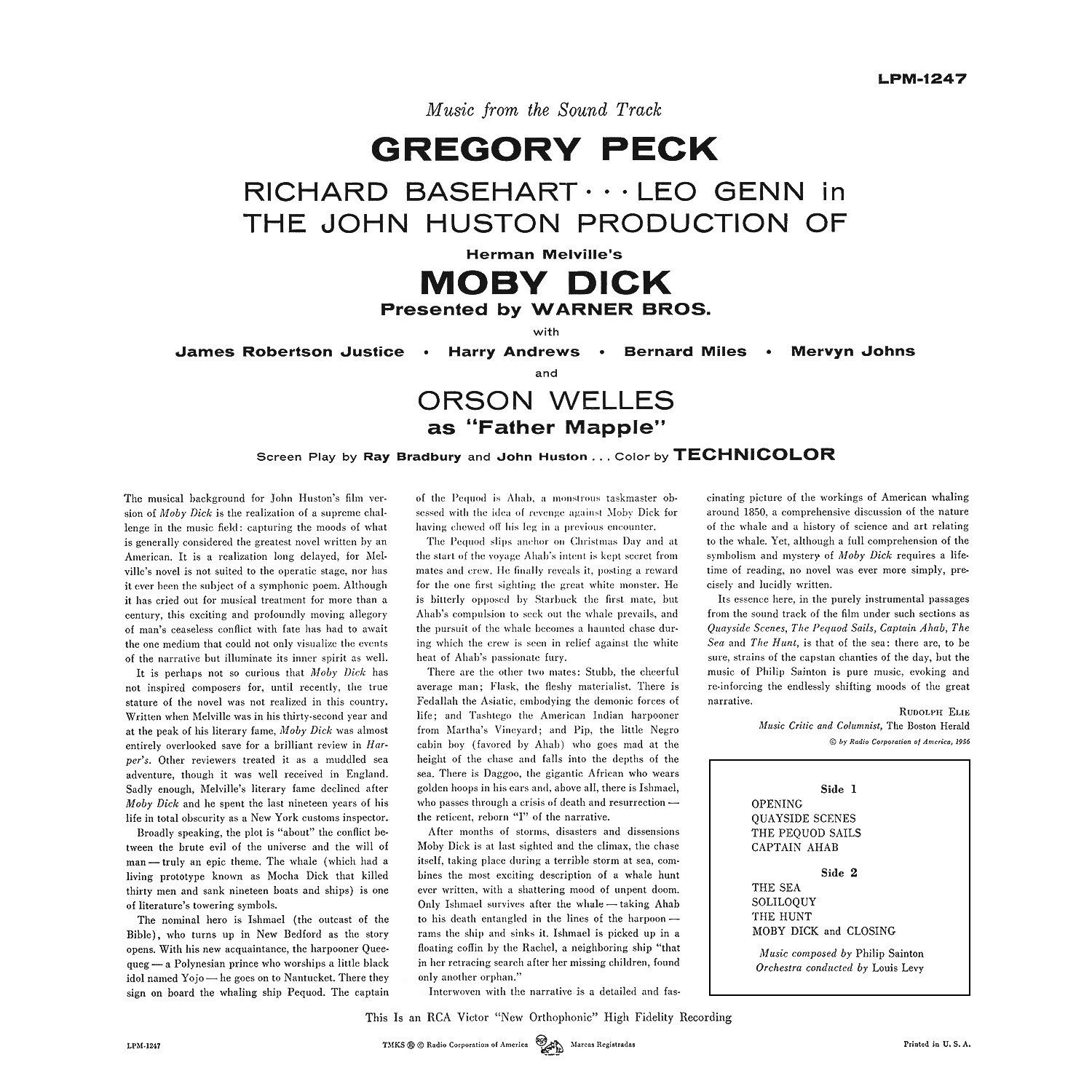

The Record

Eight sequences have been chosen from Philip Sainton’s big score and placed under various headings, ‘Quayside Scenes’, ‘The Hunt’, ‘Captain Ahab’, and the like. From the grave beauty of the opening to the fury of the end, the music has a sweep of composition that reflects the freedom in which it was created. The strong poetic writing calls up a constant feeling of the ocean, now lively and vigorous, now lonely and menacing. ‘The Sea’ is a particularly haunting sequence – its strange, high, soft dissonances voicing the hazy melancholy of the men, stretched out in the shimmering heat on the decks of the becalmed ship. Here, disassociated from the picture, the music reveals its self-sufficiency and a striking power to sustain the mood and feeling of its subject.New

The Composer

Film Music Notes: Summer 1956

Publication: Film Music Vol.XV / No.5 pp. 3-6

Publisher: New York: National Film Music Council

Copyright © 1956, by the National Film Music Council. All rights reserved.