John Scott: Savage Symphony

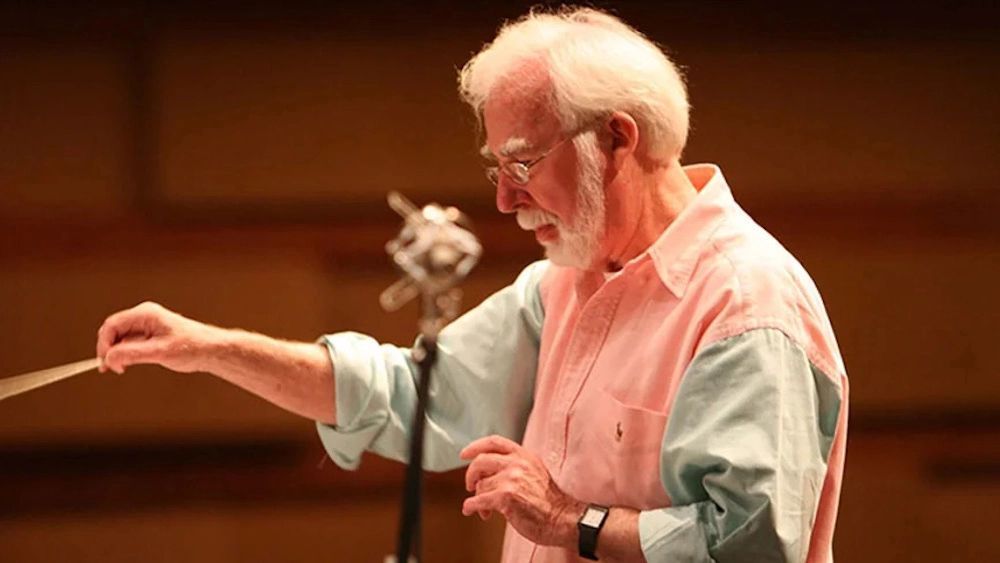

Photo by Bill Dow - All rights reserved © 2600

Originally published in Starlog Explorer #7, June 1995

Text reproduced by kind permission of the author David Hirsch

“Why didn’t John Scott take off?” asked Joel Goldsmith, composer of the scores for MOON 44 and THE UNTOUCHABLES TV series. “Haven’t you wondered about that? Why didn’t John Scott become a big-time film composer? That baffles me more than the no-talents getting these big movies. They’re flash-in-the-pans. There’s no longevity there.”

Scott has developed quite a following within Hollywood’s film music community that swells with both admiration of his talents and a total bewilderment at how little the town has properly used them. Scott still struggles to prove his merit, despite enjoying such successes as THE FINAL COUNTDOWN and GREYSTOKE: THE LEGEND OF TARZAN, LORD OF THE APES. He has even surprised his fellow composers by creating, as if by magic, brilliantly powerful scores for classic turkeys like KING KONG LIVES and YOR, THE HUNTER FROM THE FUTURE.

That struggle to rise to his full potential actually began several years earlier while growing up in England. Born on November 1, 1930, Scott notes that his interest in music came from his father, who played both the clarinet and the viola. “He was in the Bristol Police Band in the 1930s, when all the police regiments had their own bands. My father started me on the clarinet. When I was 13, I used to work six days a week in a musical instrument shop and would save up for a half-hour lesson on Saturday, but I never had time to practice! So, I joined the Army at 14 as a boy musician. I loved music and couldn’t think of any other way of getting training.” Scott actually first played the harp in the Army, eventually expanding his studies to the saxophone and flute.

Upon his discharge, Scott continued performing with various jazz and dance bands. “I really didn’t want to write at all. I wanted to be a performer and I joined the Ted Heath Band, which was very well-known in England in the 1950s. Eventually, I started doing some arrangements and compositions, which were always jazz-oriented. Some people from the EMI background music library wanted to get some modern music for tracking purposes into their catalog, so they contacted me and gave me a writing assignment.”

Studies in Terror. Scott had first been exposed to film scoring as a session musician. “I worked with John Barry on his first film, BEAT GIRL [1962], and DR. NO [1962], Barry Gray on the TV series STINGRAY [1964], as well as various other film composers,” he says. “It was amazing that I really didn’t see myself as a writer until I saw Henry Mancini at work. I did CHARADE [1963] playing flute & saxophone. I would look at his scores during the break and see how he worked with a stopwatch, matching the action on screen. I was absolutely fascinated.”

“Mancini’s music was exciting to play. I could see the film without the music, then play the music without the film, then see the two together. Suddenly, it was so dynamic. He was a great dramatic writer and I never really understood why he didn’t go right to the top of dramatic score writing. With the combination of songs like ‘Moon River’ [from BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S (1961)] and his dramatic skills, I would have thought it would have lent to going that way. I guess we don’t choose the way we go. We fall into it, or we’re led into it.”

While Mancini’s pop song hits dictated the path of his career, Scott found himself forced toward his destiny when fate left him few options. “I had an operation on my jaw due to a cyst in the jawbone. So, I had most of the lower left side of the jaw cut away. As a result, I’ve never really played a woodwind instrument since. That really turned the tide to writing full time. I was trying to do it all until then - write and play 24 hours a day!”

With writing remaining as his only way to make a living doing what he loved, Scott plunged headlong into his new career as a film composer. His first movie was A STUDY IN TERROR, a 1965 Sherlock Holmes thriller starring John Neville, which pitted the detective against Jack the Ripper. As a first assignment, it was a trial by fire. “For a completely green writer, I actually got a lot of time on that film,” Scott recalls. “It was something like five to six weeks, which is quite a luxury. I can remember being so nervous, writing this horror music, that I would play a chord at the piano and jump into the air!”

Scott’s uneasiness may have come not from the film’s content, but the producer’s manner of running a tight ship. “It’s good to be trusted, but with people like that producer… He was a megalomaniac who wanted everything his way. I thought I was learning, but I had to do it his way. In the end, I felt his way was not the best way. When you see the dagger, he wanted you to hear the musical chord. There are much better ways of sustaining atmosphere and suspense. Save it until someone appears, the hand on the shoulder, all those cheap tricks!”

Through his work with other composers, especially Mancini, Scott learned that sometimes he would have to fight to score a scene by his instincts. “I used to witness Mancini arguing with producers. He had a terrible time once with a scene where someone drops acid into someone else’s eye from an eyedropper. The producer wanted the music to start when we see the eyedropper and Henry wanted the music played from the point-of-view of the one who’s going to get it in the eye. He reacted to that idea and felt he should save the music for that time. He had very logical ways of approaching it.”

Over the next several years, Scott scored several British murder mysteries, thrillers and comedies. Among his films were THOSE FANTASTIC FLYING FOOLS (1967), a spoof of Jules Verne’s novel FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON, TROG (1970), wherein anthropologist Joan Crawford discovers the Missing Link alive and well in an English cave, and PEOPLE THAT TIME FORGOT, the 1977 sequel to the film adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT. While several films were successful, some were not. In each case, though, Scott committed his full resources. “If you have a really great film that works, it’s a luxury,” the composer points out. “Unless you’re a fool, you can do anything. You’re not going to damage the film. Whereas a weak film relies so much on music, and music can only do so much. Nevertheless, you must try and do all you can for the bad film. You’re bound to feel more challenged. When I do any film, I try and regard it as the most important thing I’ve ever done.”

Notes to the Countdown. By 1980, Scott would score the first of several major motion pictures that should have established him on Hollywood’s “A list.” The first was THE FINAL COUNTDOWN, a modest box-office success which has since become popular TV fare. Kirk Douglas starred as the captain of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Nimitz, which finds itself transported back in time to the eve of the Pearl Harbor attack and faced with the chance of stopping the Japanese fleet with modern weaponry. “I loved The Final Countdown. It was an intriguing story that really got the mind working.”

For this film, Scott pulled out all the stops, literally writing an ode to Naval air power – in fact, much of the score was reused in the documentary WINGS AT SEA. Charging drums and sweeping horns created the musical might of the NIMITZ, while the horns, combined with string instruments and woodwinds, added an air of mystery. Despite all the powerful images that would easily motivate the composer, his one real challenge was the time warp itself. “It didn’t work too well in the end because we waited forever for special FX that never arrived!” Instead, Scott was forced to develop his musical motifs for the storm based solely on storyboards.

Sharing the good with the bad, his next two films were less than stellar. First came HORROR PLANET (a.k.a. INSEMINOID) in 1982, an ALIEN clone that suffered from a tight budget. Even worse was the internationally produced YOR, THE HUNTER FROM THE FUTURE (1983). “I really worked hard on YOR, as you can imagine,” Scott admits, “because it was a really dumb film, but somehow good to write for. It had all these strange situations that people got into. It was a kind of important film for me at the time because it was a Columbia Pictures release and they put me up in one of the great Rome hotels, the Imperial or something. I had a suite and my piano was there. We didn’t have a lot of time, only three weeks, and it was wall-to-wall music. I worked day and night. Then, we recorded with this terrible orchestra. It was the worst. I’ve vowed never to go back to Italy to record again. There were all these kids in the orchestra – students! They told me that if the orchestra was over a certain size, you had to have a certain amount of students. They were putting the money into their own pockets and just getting anyone. They think that if an orchestra is big, you can cover up these things.”

To add insult to injury, in the end, only four cues of music were utilized and the bulk of Scott’s score was replaced by synthesized disco music by Guido and Maurizio De Angelis, when the filmmakers thought they could save the movie by adding a “hip” score. “I was very disappointed that the music was thrown out, especially in favor of the music that replaced it. The Italians are particularly good at that. I mean, if it had been replaced with a good score, well – I can’t say that the new score was bad – Yes, I can! Bad electronics with all these Denny Terrio dance-type vocals, by a singer named Oliver Onions, no less, trying to sound American,” Scott observes, shaking his head in bewilderment. The composer has taken some small solace in the recent release of his complete YOR score on CD.

Score of a Legend. Scott’s next film featured his most famous score. Unreleased to date on compact disc, bootleg CDs made from the original vinyl record for GREYSTOKE: THE LEGEND OF TARZAN, LORD OF THE APES recently showed up on the collector market for a whopping $150 per album. Produced and directed by Chariots of Fire’s Hugh Hudson, this 1984 version of the early life of Burroughs’ oft-filmed character followed Tarzan’s childhood in the jungle before his only living relative attempts to civilize him. Christopher (HIGHLANDER) Lambert starred as Tarzan and Sir Ralph Richardson made his final screen appearance as Lord Greystoke.

The early part of the film presented Scott with a composer’s dream. Since much of Tarzan’s adolescence is spent with the apes who raised him, the lack of dialogue demanded that Scott pick up some of the narrative with his music and, as he put it, “Speak for the characters who could not.” During these sequences, he chose to utilize a contemporary sound for his score. “I’m surprised now that the African side didn’t occur to me,” he remarks when asked if he had ever considered basing that part of the score on tribal rhythms, like Hans Zimmer did for Disney’s THE LION KING (1994). “Hugh Hudson would have probably wanted actual ethnic music as opposed to re-created. The Victorian aspect, for Tarzan’s time in England, was a foregone conclusion.”

“I was actually the third composer on that film. There were two other scores already disposed of. One was all made up of various classical pieces like the music composed by Gustav Holst and Sir Edward Elgar. Some of the Elgar pieces remained because Hudson had his mind set on them for the museum sequences, which was absolutely right. Apart from that, there was no need for any period music.”

GREYSTOKE did lead to better films, though Scott once again saved the day with his powerhouse action score for Dino De Laurentiis’ lackluster 1986 sequel KING KONG LIVES. Scott credits director John Guillermin with helping pull off another of his most popular scores. One of its highlights is “Lady Kong Gets Gassed,” a sweeping four-and-a-half-minute action cue performed with all the power of the Graunke Symphony Orchestra. “I guess I believed in the scene,” Scott notes of its inspiration. “I admired Guillermin and thought he was a very good director. In fact, he gave me one of the best music briefs I’ve ever had from a director. He knew exactly what he wanted, what he wanted me to do, and where the music should stop and start. That was a very refreshing change. Generally, directors and producers don’t know what music can do. I appreciate people who can tell me what they want from a scene. People who neglect to do that, then hear the scene and tell me, ‘No, that’s not what I want,’ annoy me. It’s partly their fault for not telling me what they’re thinking about.”

In 1988, Scott found his music supporting an important scene in DIE HARD, though he was never hired to work on the film. Having defeated the terrorists, hero Bruce Willis and his wife Bonnie Bedelia finally meet L.A.P.D. officer Reginald Veljohnson amidst the building’s wreckage. The cue heard during the sequence was actually a piece called “We’ve Got Each Other,” written by Scott for the 1987 film MAN ON FIRE.

Music in the Future. Scott’s latest works include the espionage thriller THE LUCONA AFFAIR, the Western WALKING THUNDER, and the recently released FAR FROM HOME: THE ADVENTURES OF YELLOW DOG. “It’s a serious story of survival on the order of LORD OF THE FLIES,” he says of Yellow Dog. “A young boy and his dog are lost in British Columbia and must survive by their wits. Currently, I’m scoring NIGHTWATCH. which is the film Pierce Brosnan was committed to finishing before taking over as James Bond.”

On the horizon loom two very different films that have started his creative juices flowing. “Sergei Bondarchuk, one of my longtime heroes, directed one of my favorite films of all time, the 1968 Russian-made WAR AND PEACE. He finished an eight-hour film based on the Nobel Prize-winning novel QUIETLY FLOWS THE DON. It’s a story that follows the rise of the Cossacks to the Bolshevik Revolution. The Don is the river that runs through their land. I’m writing the music for that.” [Luis Bacalov eventually scored the film.]

Scott’s also looking forward to friend Norman Warren’s planned remake of the 1958 FIEND WITHOUT A FACE (Sadly, the film was never made). Previously, the two worked together on SATAN’S SLAVES and HORROR PLANET. Scott is proposing to resurrect some long-forgotten acoustic instruments to create a sound he believes synthesizers can’t provide. “I think, of course, that you have to create strange atmospheres,” he says. “There are various ways of doing it. The orchestra hasn’t been explored fully yet and probably never will be. It’s always being added to in terms of new instruments, or exotic, seldom-used instruments. I really try my best not to duplicate what I’ve done before. The scope within an orchestra is infinite. One can find various combinations, and, in order to keep fresh, you just have to keep looking. I don’t feel tied into one particular way of doing things, so I try and find something different each time, although people have pigeonholed me. They like me to do big scores. I’ve noticed that, generally, they don’t like it if I do something small.”

Scott also plans to release more of his music on his own record Label, JOS Records. The decision to privately finance his own label came about in 1989 when no one wanted to put out his WINTER PEOPLE score. “Soundtracks only make money if the film is a great success, and everyone thought WINTER PEOPLE wouldn’t make it. Record producer Ford A. Thaxton came to me and said, ‘John, I think we can put it out if you pay all the licensing fees.’ So I thought, if I have to pay the fees, why don’t I put it out? I then went on to do seven Jacques Cousteau score albums, several other film soundtracks, and a collection of my favorites [which included THE FINAL COUNTDOWN, GREYSTOKE and PEOPLE THAT TIME FORGOT.] I would like a decent pressing of GREYSTOKE, so I think I’m going to re-record it and put it out myself,”

Obviously, John Scott’s future is full of work. Not on those big blockbusters that get antacids delivered by the truckload to studio offices, but smaller films that get his mind working. “I really don’t want to do a DIE HARD,” he says. “I like the personal dramas that say more to me emotionally and offer me better opportunities.”

In the end, the movies may not have been winners, but the composer has always scored.