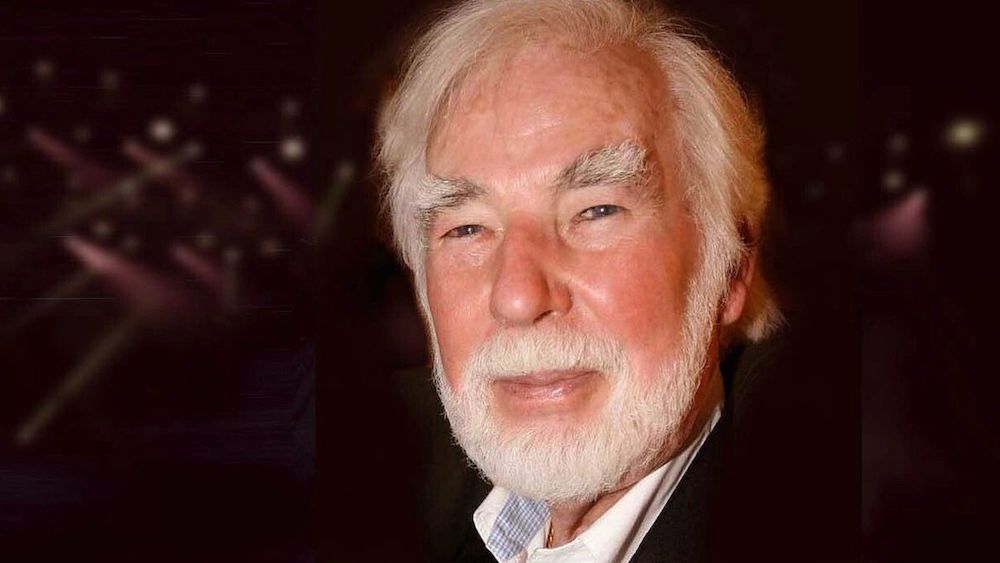

An Interview with John Scott

An Interview with John Scott by Rudy Koppl

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.16/No.63/1997

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

No matter how large or small the film is, if it has music by John Scott, it becomes monumental. From a time trip on an aircraft carrier (FINAL COUNTDOWN) and the ancient days of Rome (ANTHONY AND CLEOPATRA), to the jungles of Tarzan (GREYSTOKE) and Mowgli (THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK) to the Canadian wilderness (FAR FROM HOME: THE ADVENTURES OF YELLOW DOG) and the world’s oceans (numerous Cousteau documentaries and ABC’s 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA), his inspiration is endless. John Scott has penned over fifty-five film scores in his lifetime, and plenty of television documentaries and TV movies. Today he still writes, orchestrates, and conducts all of his film scores. Since last December he’s composed for 3 films, 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA (Hallmark Hall of Fame TV movie), MILL ON THE FLOSS (British TV movie), and THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK (released last summer in theaters). This interview was finished in June, just before he left for a holiday in France. When John was over there, Jacques Cousteau died and was buried there at the same time. Cousteau was instrumental in helping John develop his skills as a film composer and I know he will always be indebted to him for that. To sing John Scott’s praises is easy for me, but I think his music speaks for itself. What you are about to read are the views of an English gentleman and his take on an industry that’s turned upside down in thirty-seven years.

Do you have any idea on how many scores you’ve done?

I’ve never counted. I was a late starter and a playing musician up till very late. I played for all the film composers including John Barry and Henry Mancini. It was in a sense much too late that I really decided to start writing for films. And everyone knew me as a player; they think you can’t do two things well. If you are a good player you can’t be a good writer. I started actually writing for films at the end of ‘65, having played on all the James Bond movies and things like that.

What instruments did you play?

Saxophone, flute, and clarinet.

Did you have the ability to write when you were a player?

I never put myself to the test because I was a professional musician. When I decided I was really serious about writing, I had to stop playing and spent time studying. It took about a year doing various exercises, talking music from the compositional point of view rather than the playing point of view.

What was your first film score?

A film called A STUDY IN TERROR, about Sherlock Holmes, and I think it was 1965. An American company shot this in England with English actors.

Don’t you find it unusual today that you orchestrate as well as compose your film scores?

No. I consider orchestration equally a part of composing. I’m very serious about my music. It’s not a business to me. I hope it never does become a business, but if it was a business and if I was doing 8 or 10 films a year possibly I would have to resort to an orchestrator. But when you look at all the serious composers throughout the history of music, I’m talking about serious composers’; tell me one that used an orchestrator? Handel, Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Mahler, Stravinsky, Bartok, who used an orchestrator? Nobody.

Isn’t the amount of work to compose and orchestrate a score overwhelming?

It depends on the way you think about music. When I conceive music in my head I hear the full sound. Why shouldn’t I write it down as I hear it? There are certain composers that hear just part of it. They hear the melody line and then give it to an orchestrator. It’s very typical and prevalent in the business now that through the advent of computers, MIDI, and synthesizers people are composing through their fingers. Their fingers onto the keyboard, out through MIDI into a computer. This is notated by the computer and then is given over to someone else to straighten out, to make sense of, and then to orchestrate. In other words, these people are not hearing orchestration. They’re hearing at best a melody and rhythm. A mood let’s say. To me, orchestration is a part of the music. It’s one of the most important ingredients of the music.

How do you feel being one of the few who write, orchestrate, and conduct their own scores today?

There are certain composers I know, whether they use orchestrators or not, who do it all. I’m talking about people like Bruce Broughton and John Williams. These composers do exactly what I do. I don’t think that I’m unique. Most film composers have to conduct their own music. Incidentally that does not make him into a conductor. But a composer like Bernard Herrmann completely scored all his films. Why? Because he felt the same as me, he heard it as he conceived it in his head. And the other thing is that Bernard Herrmann’s scores and sound stand out from everybody else’s. He’s very much copied. He’s an original, the copies are not originals, but he is.

Is there any orchestra you worked with that stood out among the others?

I hear a lot of film composers criticizing orchestras and saying this orchestra is great or this orchestra is not so great. That might be true, but there isn’t that much difference because professional musicians have all earned their places in those orchestras. When it comes to film music, it is basically much easier to perform than a lot of orchestral repertoire. If they can play Stravinsky and Bartok, they can certainly play film music with their eyes closed because it doesn’t make those kinds of demands. The orchestras that I’ve worked with here (in the USA) have been wonderful. Absolutely wonderful! The orchestras I’ve worked with in England have been wonderful. They are different, but different doesn’t mean better. You compare one novel with another, they’re different. You can say this orchestra has a great string section or a great brass section, but all in all I think that I’m seldom dissatisfied with the orchestras that I work with. And having been a player I also feel much more of a rapport between the orchestra and myself. I’m in their place. I have played for stupid conductors and I know that when I stand up in front of an orchestra that I’ve never met before, everyone is waiting to see how I work. You know, they test you.

I can also remember working with the London Symphony Orchestra and at the time André Previn was their principal conductor. The producer of the film was Steve Previn, his brother. It was a film called HENNESSY. Steve said, “I’m going to take you to meet André and he will tell you about the orchestra”. André said the orchestra will test you out and if you can make it you’ll be all right, if not – forget it. He sent the fear of God up me. I got there with the orchestra, we started and it was just wonderful! Everybody in most orchestras is really so cooperative. I also conducted in Germany the RSO Berlin Symphony Orchestra, a really fine orchestra and I don’t speak the greatest German. I can remember being scrutinized by everyone. You get up on the podium and everyone is looking at you. They are sizing you up and you have to break through that. Also I was in Seattle recently and once again a similar situation occurred. You stand up there in front of the orchestra and you break through. Then everything is great after that point.

How did you get the job to score THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK?

Paul Talkinton, my business manager, put me in touch with the people making JUNGLE BOOK last spring. I met the director Duncan McLachlan and he said, “We’d like you to do the picture. Here’s the script, take it home and read it,” which I did but didn’t hear anymore about it. I went back to England and got on with my work, 20,000 LEAGUES and all that. Then they called and said. “We want you to do the picture, like can you do it straight away.” Of course I was doing something else. As soon as I was clear I got on a plane and came over and met them all again. That is the way I did THE JUNGLE BOOK.

Which orchestra did you use for THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK?

It was basically The Seattle Symphony, but I don’t know whether we will use their name because it was an outside contractor that contracted the orchestra, basically drawn from The Seattle Symphony. We did four sessions with 85 players and two sessions with 67. Six sessions in all.

Can you explain the development of your themes in this film?

There are probably three or four themes here. Let me explain my working methods. I try for an overall theme and then sub-themes for various characters or situations. In the case of THE JUNGLE BOOK here is my overall theme which is a feeling of certain aspects of India, the jungle, etc. And then there are sub-themes for Mowgli the main character, the bear Baloo, the wolves – he was brought up by the wolves of course, and in this case he befriends this little monkey called Timo, so Timo has a theme as well. In all my films it’s generally restricted to a main theme and sub-themes that come in. But they are always treated according to the dramatic situation in the film at the time. So if we’re talking about Mowgli, there’s a playful theme for him that’s heard very early on when nothing has really happened in the film. Then this thing takes on other shapes, for instance he finds himself on this train and he’s kidnapped, someone wants to catch him and take him back as a wild boy to the Barnum & Bailey Circus. When all these things go on, his theme turns into excitement, adventure at times, comedy, according to the situation. But I really wanted the theme of THE JUNGLE BOOK to have nobility and a sense of India. I really wanted to use the Sitar as featured instrument as I did in a film quite a while ago called THE LONG DUEL, which was set in India. We had so little time and financial resources. They were pleading with me to cut my orchestra down because they didn’t have the money in the budget. I stuck to it. I did it in basically six sessions, it should have been ten. We did no overtime whatsoever. But when it came to the luxury of an instrument like a Sitar, which is very specialized and you pay a specialist’s fee, and then it was out of the question. In this score there are some classical or traditional pieces fused into the music.

Could you explain what those score were?

They were there generally for some comical music. I use a little bit of ‘Scheherazade’ in one place where the owner of the monkeys is in this big chase on top of a train. It’s absolutely ridiculous and it becomes so farcical. I decided to use this little bit of ‘Scheherazade’ that everybody knows. I thought it would add to the fun and confusion of the thing. And later on there’s a scene where this old soldier, who has made himself king of this derelict lost city, is talking to Mowgli about being his successor and there’s various things glorious like war. I use a little bit of Wagner’s ‘The Ride of the Valkyries’, which has been used in APOCALYPSE NOW. There’s a little bit of ‘Orpheus in the Underworld’ when the person who’s captured Mowgli is talking about taking him back to America and how he’s going to be a star appearing in front of all these people. Then I play the Can Can which is typical of the music played in circuses. Also ‘Rule Britannia’ because he’s an English soldier. The idea was implanted in my head and I found it fun to incorporate it into some of the chaos here.

Do you feel this might be one of your most complete scores representing many styles up to this point?

When you write music for film you’re serving the needs of the film. I think it should be within the compass of a film composer to be familiar with various musical styles. You’re called upon for all kinds of music. One moment you’re doing thriller. The next moment you’re doing a war film, a sports film, a love film, they’re all different and require different things. They even require different kinds of orchestras, jazz, pop, hard rock, symphonic, string quartets, piano solos, everything. The knowledge of it all is very much required. It so happens I was a jazz musician, so I feel I can write for big bands, jazz groups, pop groups, and symphonic things.

What kind of orchestra did you use for 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA?

This was recorded in England and it was the Philharmonia Orchestra. That’s quite interesting because the Philharmonia is one of the great orchestras in the world; it’s one of the orchestras that has a film history. For instance I think that most film music collectors know SCOTT OF THE ANTARCTIC, the music was written by Vaughan Williams. And this music became his Sinfonia Antarctica. The Philharmonia was the orchestra that recorded it. My largest orchestra here was 65 pieces, but this is basically a television film. I mean that’s large forces. We also recorded it in four sessions and it’s a two hour film.

How many themes did you use here?

There was the generic theme which was really about the Nautilus, this incredible submarine. The theme has a sense of mystery; it’s all about Nemo and his underwater world. There was a theme for the love interest between Sophie and Ned Land. Then Capt. Nemo had his own theme, a little bit introspective. There was also a theme for the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln, which was the ship that he went to war against. So, four themes.

Explain the deep stirring and surging string-like theme at the opening of the film?

This is a story about a naval captain who’s condemned to roam the oceans aboard his boat, a kind of ghost ship, forever and ever and ever until he’s redeemed by the love of a woman who’s prepared to give her life for him. I saw Nemo as wandering the ocean, a type of underwater Flying Dutchman. During that theme there was a descending arpeggio with flute and percussion.

What did you identify this with?

That was an idea that came from the feeling of the Nautilus submarine. You know, the sonar kind of rebounding. I know they didn’t have sonar in those days, but I saw it as a kind of submarine motif. You hear this thing and you think of below the waters.

Was it my imagination that I perceived bit of Strauss or 2001 – A Space Odyssey here?

That’s part of it. Zarathustra and all the rest of it. But taking place below, not above.

Do you feel your music portrays the drama here?

It definitely does and (on the album) will be released in sequence as it was written for the film. I think that you can follow the story through, so it must portray the drama. I’ve made one little deviation and that’s why I start with the second piece rather than the first piece. I felt that this was a better way of entertaining a listener. The first piece of music is the titles. It’s the very mysterious underwater world of the Nautilus and Capt. Nemo. Then starts the second piece which is these people aboard a cruise ship, late 19th Century or early 20th Century. So it’s a little bit of a change, but it’s saying these are people on board a cruise ship, excitement at sea and all the rest of it. Then come the titles and now we’re into the mystery of 20.000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA. This fires the imagination. We don’t know what’s under the sea. When we go for a swim there could be a great big creature getting ready to bite off our legs. I’m sure you’ve had that feeling out in the ocean when you’re swimming about. So this second piece conjures up the feeling of the mystery underneath the surface of the ocean.

When you composed this were the special effects finished?

No. You’re writing along the same time the film is being made, especially one which depends on special effects. So the only time I saw the film completed, was when it was aired on television. You’re using your mind, rather than responding to a visual image. After I finished recording the music they were still working on it. They worked out how long these periods occupied in the film, but they still had not come back from the special effects house. There was no budget for any kind of changes. You get one shot. Everyone is allowed to edit, re-edit, shoot, re-shoot, and the composer goes in and gets one shot.

How do you incorporate the synthesizer in your film scores?

I incorporate it in my scores as a sound that is complementary to the orchestra or a sound I cannot get from the orchestra.

Who was the vocalist on the beautiful piece ‘Over Atlantis’?

She’s a very fine singer who specializes in early music, like madrigals and motets and things like that. She came and did it as a favor for me. This was recorded live with the orchestra. However, if I had looked at the film and been inspired by what I saw, probably I would have written nothing. You have to use your imagination. You think this Nautilus is supposed to be sailing over Atlantis. I read the script all the time I’m writing. Mt. Atlantis is still pouring out lava, like it did when Atlantis was ruined. They’re now sailing over it and it’s so hot, The Nautilus dare not linger here. I could see pictures of this city, thinking how it was and how it is now. This inspired me to write this particular piece of music.

How do you consistently come up with beautiful pieces like this in your scores?

I pray to God!

One of your more romantic pieces here is ‘A Proposal of Marriage’…

It takes place on the deck of the Nautilus. They have just left the area of Mt. Atlantis and they’ve come up on the surface. Nemo and the girl are taking in the air. It’s a very romantic night with stars out. He is going to propose to her, but she rejects him. The picture is peaceful and romantic and in total contrast to the destroyed city of Atlantis. Nemo’s theme is a development of that Strauss-like theme, as you call it. It develops into that, but it can take on different forms. He’s an introvert, a very complicated person with many facets. So that theme also changes according to his facets. In the case of this one, it’s now highly romantic because he’s discovered the person he wants to make his wife. This is exactly the same music when we first see him on board introducing himself across the table, but now this piece of music is highly mysterious, almost to the extent of being devious. Very deep, low, and introvert. The same thing, but different ways.

When you write a film score, do you get ideas from other places than the film?

For me, writing music for a film is a struggle. It’s a tremendous struggle. It’s tiring, when I start on a new project. Invariably I feel that I can’t write. I have to go and reassure myself by listening to something I’ve written in the past and think, “Yes I can write, but it’s not happening now.” It’s a struggle to drag every note out. It amazes me when I come to it afterwards that it sounds easy. It sounds as if it all flowed, but it doesn’t, it’s got to be dragged out. Do external circumstances influence me? No. The thing that influences me is the struggle to drag something out.

Why are you using the oboe quite a bit in 20,000 LEAGUES and THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK?

This has been remarked before. It might be that the oboe draws attention to itself when it’s used. Whenever I find myself over-doing something, I try and stay away from it. When I did the music for FAR FROM HOME: THE ADVENTURES OF YELLOW DOG, I felt that lover-used the harp. So the next couple of scores I never used a harp in order to bring myself down. Now there are other devices that I feel I’m over-using, so I’ve got to leave them out of scores. And it could well be that now I’ve got to leave the oboe out of a couple of scores.

Do you feel your score of 20,000 LEAGUES captured the spirit of Jules Verne?

After I finish a piece of music I can’t listen to it, I can’t be the judge, I’ve done my best. I’ve probably failed, but I’m too close to it to sit back and say that’s great or that’s not good or whatever. Now that a good couple of months have passed, I’ve actually listened to it again. And as a work I feel that it stands up very well. As far as complementing the film, as far as being a great piece of film music in film, I still can’t answer you. It satisfies me as music, there’s a difference. This is the second Jules Verne film I’ve done. The first one was in England called ROCKET TO THE MOON. It was a great thrill to write. It’s a score that I’m satisfied with to this day. I said somewhere I’d give my eye-tooth to write the score for 20,000 LEAGUES. It was thrilling to think that I had the chance to write the music for 20,000 LEAGUES. That is fulfilling for me.

What scores have you composed since 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA?

I recorded 20,000 LEAGUES in the beginning of December ‘96. That was followed by MILL ON THE FLOSS. This is a very famous English novel written by George Elliot. She was one of the first feminists who built this around the role of a woman in her time. This is like mid-19th century, 1850 or 1860. MILL ON THE FLOSS is a two hour film made in conjunction with the BBC in England and it will come out as a feature film in certain territories. It’s a little bit like ENCHANTED APRIL, if you remember that one.

After that I did a Thomas Hardy story. He is another English novelist and we recorded that right at the beginning of the year in Slovenia. I think it is due for a summer release on the big screen. Then there was THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK. (When Jacques Cousteau died last July, we asked John whether he’d score any more films for the Cousteau Society) I am currently working on LAKE BAIKAL – BENEATH THE MIRROR, a documentary about the largest lake on the planet, in Northern Russia. They had already selected ‘library music’ and that was the way it would have been transmitted. I am glad that they are giving me the opportunity to show my appreciation and write the score. I will use a medium-sized orchestra and write it purely for the film, so it won’t be sentimental, but I will issue it on CD as a tribute and possibly include a specially written piece in the shape of a memorial.

It would be ideal for me to write one or two films a year. I’d be happy if they were good films, but I think the A-list composers are writing absolutely continuously. You know, 8, 12, 14 pictures a year.

What do you think of film scoring today?

I think there will always be good composers coming up. The genre will carry on. Having said that, I think there are troubles. I acquired my knowledge for writing music for films through documentaries. First of all I had Jacques Cousteau, who was just wonderful, who was one of my greatest teachers. He allowed me to write, and he encouraged me to write and they provided me with orchestras to work with. That seems to have gone now. The area of documentaries which is dominated by the Discovery Channel, you hear what’s happening on those? Everything is synthesized. There’s no budget anymore for music. Also there’s fault to be laid with the producers and directors, because they are of the opinion that a synthesized score can be heard immediately. They hear how it complements the film. They can ask for changes that can be accommodated on the spot.

And that’s where music rests nowadays, in the synthesizer and in MIDI. This takes away the demand for compositional skill and orchestration skill, because even though one is using synthesizer and sampled sounds, there are not too many instrumental orchestral sounds that are convincing. What it does do is take away from the demand for a composer to gain more knowledge of scoring and orchestrating. To me orchestration is composition. When a composer is content to delegate that part to someone else, quite often of lesser skill than the composer, then things are in trouble. Documentaries gave me the chance to learn, experiment, and write. Nowadays the budgets are miserable, because people think synthesizers are serving them well. A composer didn’t have to jump in the deep end; he could try in the shallow end and develop skills. Where does one go nowadays? It’s straight in the deep end.

What direction is your record company JOS going in?

JOS can only put out things that are not snapped up by the majors. The success of JOS depends on the support of people who buy through mail order, people that like my music, which means they are true film music buffs, and they will accept my music even though it’s not tied to some major success. I’m very proud of NORTH STAR, but the film itself went nowhere. There was another score written and it didn’t rescue the film. I save the music because no one’s going to see the film and it’s something I’m very proud of. But where will that take JOS as a company? It’s a kind of indulgence, because a lot of these things that I put out would just be locked up and no one would ever hear them.

Funny enough, we’re selling out at last of a couple of CDs. So we either have to print up again or take the risk of having a thousand CDs in our garage. I just sold the last of ‘John Scott’s Favorite Film Themes’. So that will become sought after. We ran out of CAPE HORN and PARC OCEANIQUE COUSTEAU as well. But we made a second printing of PARC OCEANIQUE.

What are your current and future plans?

I have a couple of commissions. I’m writing a guitar concerto for Gregg Nestor, an orchestral work for the Philharmonia Orchestra, and I want to write a concerto grosso. Concerto grosso means setting four or five solo instruments against an orchestra. They all have virtuoso parts and they play together, but they are also contrasted with the orchestra. Whereas a concerto for violin and orchestra is one soloist and orchestra. I want to write a concerto grosso for five soloists and orchestra. That’s important to me. Also I will do more film scores, but I won’t talk about anything, I’m a little suspicious. If you talk about them they tend to go away.