20th Century Violin Concerti ABC Westminster Gold WGS-8269 - The Kammermusik No. 4 is one of a group of six compositions similarly titled written between 1920 and 1930. With the exception of No. 1, which is for small orchestra, they are all concerti for solo instruments variously accompanied. The instrumentation of No. 4, described by Hindemith as an “enlarged” chamber orchestra, consists of 2 piccolos, 3 clarinets, 3 bassoons, cornet, trombone, tuba, 4 violas, 4 celli, 4 contrabassi and 4 drums tuned to indeterminate, widely differentiated pitch levels.

The concerto is divided into five contrasting sections. I, entitled "Signal" (or Prelude) moves in a persistent non-varying four-beat pulse. Fairly dissonant, it is nonetheless related (however distantly) to the key of B flat. A trombone enters, giving utterance to a broad a-rhythmic statement, to which the cornet adds fanfare-like flourishes. The tension continues to mount, aided by several key-shifts as well as by the addition of trills and scalar passage-work by violas and celli, all poised on an ambiguous chordal structure which resolves surprisingly but altogether properly on an uncluttered B flat Major triad.

Section II, marked Very Lively, continues without pause as the solo violin enters with its own variant of the “Signal.” This is followed by a close-knit discourse in which the violin pursues a soloistic path against a contrapuntal pattern encompassing the entire range of the ensemble, retaining both integrity of line and thematic relevance. Presently the violin launches into a new and somewhat “Straussian” theme, which is answered imitatively by various orchestral groups, ultimately coming to rest in D flat Major. A brief interlude, marked Quietly, is followed by further contrapuntal manipulation leading to a shortened recapitulation of Section II.

The soloist again resumes his role as protagonist as the accompanying texture grows increasingly dense and elaborate, through which the violin billows upward like a smoke wreath, coming to rest on its topmost “D”, supported by a murmuring D Major triad in the lower strings (again marked Quietly). Once more the tempo accelerates to a Coda based on the Straussian theme, thus concluding the movement.

Section III is called “Night Piece.” The basic time-signature is 12/8, and the strings are muted throughout. The movement opens with a quiet phrase announced by the clarinet supported by the lower woodwind, alternating with divided strings. The solo violin enters (Quasi Recitativo) in the fourth measure, introducing a broadly expressive Cantilena, marked piano, with utmost calm, to which quietly moving violas and celli add both harmonic and rhythmic interest. The songful Cantilena continues, ever-expanding and rising in pitch and intensity.

Gradually the entire accompaniment pattern changes as the bass clarinet, bassoons and contrabassoon in a two-octave unison announce a restatement of the Cantilena at a different pitch-level - actually a fugal answer at the fifth below. The violas divided in octaves add to the excitement with florid passage work, while the celli and bassi (also in octaves) fall into a rhythmically unvarying pattern of eighth-notes, pizzicato.

The violin line is interrupted by the hitherto silent E flat clarinet, which usurps the main melodic interest for one measure, marked Poco Accellerando e Crescendo Molto, followed by the indication Slower than the Original Tempo. All the strings and lower woodwinds fall silent as piccolos and clarinets (E flat and B flat) establish a new rhythmic pattern (Pianissimo and Staccato), under which the solo violin enters quietly with a melodic line quite different from the original Cantilena, though obviously some subtle relationship exists. As the violin continues, the rhythmic pattern gradually expands, and presently the celli enter with a free canonic imitation at the lower octave. The rhythmic pattern shrinks to its original proportion as the solo clarinet announces a recapitulation of the original Cantilena, to which the violin now adds a florid, fanciful embroidery. As the clarinet ends its song, the solo violin, accompanied by divided violas and celli, drifts into a thrice-repeated three-note figure (d, f, e), two of which are accompanied alternately by woodwind and strings, while the third, written in notes of longer value, stands quite alone, coming to rest on an E natural under which the low strings add the rich sonority of C sharp Major!

Section IV, in ¾ time, bears the tempo indication Lively Quarters. The cornet announces a jaunty march-like theme, accompanied by the low strings in a busy two-voiced texture. Some sixteen measures in length, it is straightway repeated in the upper octave by the clarinets. The cornet and trombone in octaves alternate with violas and piccolos in exposing a new countermelody over a consistent pattern of eighth-notes played by an octave of celli and contrabassi. This double exposition concluded, the cornet again assumes leadership, developing and expanding the new countermelody, closely imitated by the low strings.

Now the solo violin enters, working its way (via a fragment of the new countermelody) into a restatement of the principal theme, against which the consistent eighth-note pattern, somewhat transformed, is presented by a trio consisting of cornet, trombone and tuba alternating with the lower woodwinds and strings, presenting the pattern by inversion.

Having concluded its statement, the solo violin plunges headlong into a display of virtuosity. A new thematic fragment is exposed by an octave of clarinets and bassoons, the trombone moves chromatically downward as the original eighth-note pattern emerges again, making a mighty crescendo culminating in a powerful six-octave unison, which is followed by a species of Trio, Quasi Cadenza, played by the solo violin, accompanied by an asymmetrical pattern on the four tuned drums, struck lightly with felt mallets. The tuba makes an occasional comment (Pianissimo) the last of which leads to a much varied recapitulation followed as before by the Trio, Quasi Cadenza, but without comment from the tuba. Presently the percussion pattern vanishes, leaving the solo violin alone with four measures of a repeated pattern which merges without pause into the last section.

Section V (in cut time) with the tempo indication As Fast as Possible, is actually in the manner of a Perpetuum Mobile. Delicately scored, its dynamic level never rises above a Mezzopiano with but few exceptions, confined largely to the solo violin. The high point of the section occurs at measure 113, marked Like a Waltz. Pizzicato strings play in a cross-rhythm, thus - 123/412/ 341/234 and so on.

The solo violin continues, utterly disregarding the crossrhythm, while a piccolo intones the rarest suggestion of a waltz-strain, after which order is restored. Measure 143 is marked Still Faster, if Possible and the section comes to a smiling conclusion, tinged with just the barest hint of a sly chuckle.

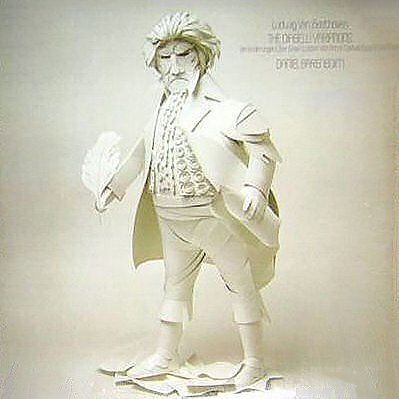

In most instances, audiences tend to be far better acquainted with a composer's early work than with the creative output of his maturity. Almost everyone knows Beethoven's 5th, but how many have ever heard his String Quartet, Op. 135?, Schoenberg's VERKLARTE NACHT, as compared to MOSES AND AARON, or Stravinsky's FIREBIRD vs. AGON? But the creative career of Kurt Weill is a complete reversal of the accepted norm.

Before his arrival in the U.S. in 1938, aficionados of the Musical Theater in America, with the exception of a relatively small “in” group, were unaware of his importance as a creator of numerous stage works in Europe. And it was not until the enormous success of KNICKERBOCKER HOLIDAY, LADY IN THE DARK, STREET SCENE, LOST IN THE STARS and others, that his American reputation became firmly established. Finally, his THREEPENNY OPERA (thanks to Mark Blitzstein's brilliant translation of the Brecht libretto) became known, and ultimately beloved in this country. Its popularity was aided and abetted by the astounding success achieved by the late Bobby Darin's recording of MACK THE KNIFE. Numerous hit songs from his Broadway productions have also gained a firm foothold in the repertory of practically every “pop” vocalist in the country. The success of THE THREEPENNY OPERA has also revived interest in a number of his earlier European stage works, particularly those written in collaboration with Berthold Brecht.

Hopefully, this recording of the CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN AND WIND ORCHESTRA will arouse a like interest in his earlier instrumental compositions. The Concerto is a fine work, written in 1924 shortly after Weill's three-year period of study with Ferrucio Busoni. In some respects it is a typical product of that first wave of avant-gardism which became endemic throughout Western and Central Europe, following the unpleasantness of 1914-1918. (For the enlightenment of those who were born in the ’40’s, it should be kept in mind that the avant-garde did not spring into existence ca. 1950; neither at Donaueschigen, Warsaw, Princeton, Ann Arbor or wherever. The avant-garde, like the poor, we have always with us!).

Happily, whatever latent tendency toward nihilism he might have had were held firmly in check by disciplines acquired from Busoni. Consequently the work is firmly knit, and reveals an extraordinary insight into the possibilities of the instrumental ensemble at the composer's disposal.

Although the Concerto demands a virtuoso technique, it is not in any way a mere vehicle for the display of virtuosity. Too many things of significance are happening in the surrounding ensemble - subtle changes of color, rhythmic shifts, organisation of related thematic fragments, etc.

Particularly interesting is the tripartite middle movement. It begins with a “Notturno” lightly scored for woodwinds and the melodic use of a xylophone. Most importantly, it gives us a glimpse of Weill's early melodic facility.The second part is in the form of a “Cadenza,” both with and without accompaniment, which is followed by the third and final section called “Serenata”. The delicate interplay of color values surrounding the soloist is both subtle and beautiful. The “Finale” (marked Allegro Molto un Poco Agitato) has all the feeling of a Moto Perpetuo, interrupted twice for interludes in slower tempi, but in the end the initial tempo is resumed for a whirlwind finish.