From whisper to great orchestral breath

Between intimacy and orchestral grandeur, let us portray a composer illuminated by all images... David Reyes !

Interview based on questions by

Pascal Dupont

French version - link

With responses from

David Reyes

Transcription and adaptation by

Manon Léger

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

On the occasion of the centenary of Georges Delerue’s birth (1925), the No Limit Festival decided to pay a vibrant tribute to the French composer. During this exceptional event, an honorary certificate was awarded to his daughter, Emmanuelle, thus celebrating the musical legacy of an artist whose works have profoundly marked French and international cinema.

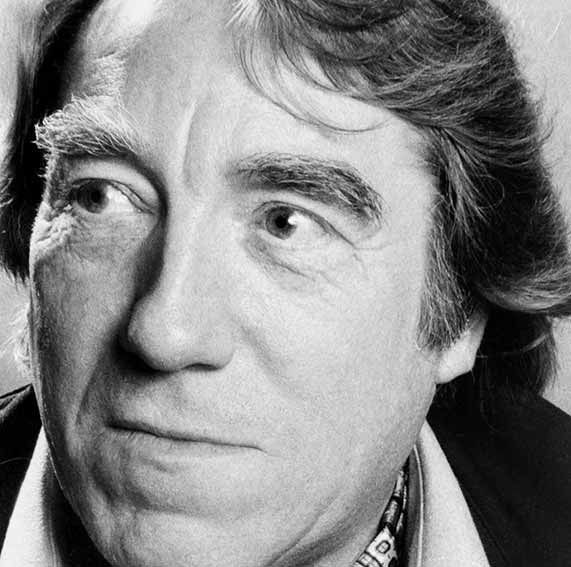

It was while preparing for Delerue’s centenary that I had the chance to discover this composer of rare talent, for whom the cello and other instruments hold no secrets. Passionate, creative, and always in search of new musical explorations, David Reyes surprises with the richness and depth of his sonic universe. Already recognized for his accomplishments, he retains the creative energy that allows him to share, with enthusiasm, the processes and passion that drive his music. A true bridge between sound and image, he knows how to reveal the depth of a story, highlight what images alone cannot convey, all while respecting the filmmaker’s universe.

For Cinescores Center, and following the centenary celebrations of Georges Delerue, I invited him to extend this adventure by delving deeper into Delerue’s work and helping to make it known beyond European borders. He generously agreed to this interview, to which he devoted a great deal of time. This exchange allows us to understand his perspective, his method, and his unique way of inhabiting both sound and image. In a world saturated with sounds and references, David Reyes reminds us that true film music remains human, instinctive, and irreplaceable.

All that remains now is to read, listen, and feel, while admiring the uniqueness and emotional power that animate his music.

Pascal Dupont: To begin this interview, I would like to draw a parallel with Bill Conti’s journey. During his studies at LSU in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, some suggested he learn the bassoon instead of the piano, believing that the instrument offered broader opportunities than a field considered saturated.

You are trained as a cellist. Was your path with this instrument similar, or did you choose it for other reasons? Could you explain how you discovered the cello ?

Was it a spontaneous choice, a passion at first sight, or a strategic decision to stand out in a given musical environment ?

David Reyes: The association with Bill Conti is amusing, because I actually know relatively little of his work — except that he scored the American version of The Big Blue, which makes me smile, as I am a great admirer of Éric Serra’s original version.

Regarding my own path, the cello was truly an asset. Thanks to it, at the age of 11, I joined the Conservatory Orchestra in Verviers. The repertoire we explored nurtured my desire to continue in music. The conductor at the time, Alain Janclaes — who was also beginning his tenure with the orchestra — carried a bag of scores ranging from Stravinsky and Mozart to John Williams’ Hook and even a Duke Ellington medley. This openness allowed me to discover worlds beyond the strict classical framework, particularly the Hook score, which left a deep impression on me. Every Saturday, I looked forward to returning to the orchestra to explore new works.

This experience, combined with my cello practice, profoundly influenced my writing for strings, which remain today my favorite family of instruments.

I also chose the cello to break from family tradition: my mother is a piano teacher, my sister a pianist, and one of my stepfathers was as well. I wanted an instrument that gave me my own space. My mother often says I chose it because I wanted to play an instrument while seated — which is also true of the piano, except perhaps Michel Berger aside, but let’s move on.

I have absolutely no regrets. The cello repertoire is magnificent. Yet, I did not initially envision becoming a performing musician or pursuing a career in music… until I discovered my passion for composition. As a devoted cinephile, I quickly realized that combining the two would be the ideal profession. This passion emerged during adolescence, unlike my sister, a piano prodigy who started at three. Early talent often leaves little room for choice; in my case, music was a conscious decision, not a predetermined destiny.

DP: The cello is renowned for its expressiveness and the richness of its timbre, both warm and deep, capable of combining power and softness in shades from dark to bright. It is sometimes perceived as the instrument that best embodies the feeling of solitude.

For you, is it primarily an instrument of nuance or a vehicle for specific narrative?

Can a cello truly “speak” ?

DR: I completely understand this metaphor, especially as the cello is often said to be the closest instrument to the human voice — which is true, both in range and timbre. It is highly expressive, with a deep sound, rich vibrato, and an extensive palette from low to high registers. I prefer it, for instance, to the violin, which I sometimes find too bright or even slightly shrill. I have also rediscovered the viola, whose timbre I greatly appreciate — similar to the cello — and I feel it is underutilized.

The cello offers immense possibilities. It is particularly effective for naturally expressive melodic lines. That said, many instruments possess their own expressive power linked to their unique timbre. I am, for example, very sensitive to the English horn, bassoon, horn, celesta, and ethnic instruments. Playing a single note on the duduk can instantly create atmosphere because of its emotional weight. Its distinction from what is usually heard in a classical orchestra gives it remarkable expressive power.

This is why, in my compositions, I enjoy combining ethnic instruments with classical orchestras — not for geographic connotations, but for their singular sonic color, which immediately captures attention. This is one of the joys of film music: you can experiment with all sorts of instrumental combinations, provided the emotion aligns with what the image conveys. Returning to the cello, I do not associate it with a single emotion. It can be lyrical, playful, or melancholic. But this versatility applies to many instruments: it depends on how they are showcased, which is precisely what makes exploring them so fascinating.

DP: Does learning the cello provide a specific advantage in understanding the symphony and the orchestra, compared to instruments like drums or guitar ?

Has it notably influenced your compositional approach ?

Not everyone becomes a composer like you, but I am curious whether your initial cello practice sparked your creativity or if writing music always seemed almost self-evident.

DR: I partially addressed this earlier. Playing an orchestral instrument was an asset because it allowed me to understand orchestration from the inside. The true privilege, however, was being part of the orchestra: rehearsals offered the chance to dissect orchestrations live.

I must admit, I am quite poor at writing rock music… If I had been a drummer, I would likely be more comfortable in that domain. Everyone has their strengths.

As for composing itself, I was not initially inclined toward it. Music ran in my family, and I wanted to take another path. I considered journalism, pharmacy… or even Louis de Funès! I thought of becoming a filmmaker, as I was far more passionate about cinema than music. Composing seemed out of reach. To write film music, I would have needed to live in Hollywood, not Verviers! My initial idea was to make my own films to score them. Eventually, composition became my career almost despite myself.

In hindsight, learning piano would have helped a lot. My mother tried to teach me, but I refused categorically! The creative spark came not from the cello but from cinema. Cinema made me dream, and music allowed me to enter that world.

DP: You later specialized in composing film scores.

Which early film soundtracks truly caught your attention ?

DR: Film music undeniably sparked my desire to compose, far more than classical music, though my first aesthetic shocks were linked to it. For example, Richard Strauss’ Alpine Symphony was my very first CD, and Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé remains a model of orchestral perfection for me. Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians also had a profound impact, shaping my later writing.

Film music, however, had an additional dimension: it heightened the emotion of images while delivering lyricism, melodic richness, and heightened expressiveness that moved me from childhood. Foundational discoveries include John Williams’ E.T., Henry Mancini’s Basil, Detective, and Alan Silvestri’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit. These scores imprinted themselves indelibly on me.

The first film I ever saw was Dumbo. Oliver Wallace’s music left an unforgettable mark. Revisiting it recently confirmed the extraordinary mastery: a score that stands on its own yet aligns perfectly with the imagery, never succumbing to caricatured mickeymousing. The scene where Dumbo’s mother rocks him behind bars remains one of the most poignant in cinema.

Over the years, other works have continued to shape my thoughts on music and image: Bruno Coulais’ Microcosmos, Éric Serra’s The Fifth Element, Thomas Newman’s American Beauty, and John Powell’s Jason Bourne trilogy. Each discovery demonstrates the rigor and inventiveness of this singular language, inspiring me to strive for the same level.

DP: Jennifer 8, with Christopher Young’s score, features cello passages intertwined with the story, as the protagonist, played by Uma Thurman, plays the instrument herself. Which moments in your work have given the cello a similarly pivotal narrative or emotional role ?

DR: I haven’t seen Jennifer 8, but I know Christopher Young’s discography. I must have close to 5,000 soundtracks in CDs and digital formats, because I listen to almost everything, even unseen films. Young is remarkable; I particularly love Bless the Child. Jennifer 8 is a beautiful album, and I will dive into the film after this interview.

In my works, the cello peaks in Les Rivières Pourpres. Other passages I cherish appear in Derrière les murs or Sauvages, usually for expressive character. In Les Rivières Pourpres, however, I explored the instrument in all its facets, “turning it inside out.”

DP: One of the most original sounds I’ve heard in film music is Keith Emerson’s Nighthawks, where cello and double bass are manipulated with synthetic effects, creating a dense, atmospheric texture. Your Les Rivières Pourpres TV adaptation has a similar innovative use of cello. Could you elaborate on this blend ? Do you plan to continue manipulating traditional instruments to explore new textures when creative freedom allows ?

DR: I don’t know that film or composer, thank you for the reference — I’ll look into it.

For Les Rivières Pourpres, I wanted the cello sound to be singular: a little “dirty,” crushed, rough, matching the series’ dark atmosphere. Lyric playing wouldn’t have worked. I treated the cello not just as an instrument but as a sonic material: striking it for sounds, using the bow unconventionally, or even rubbing the strings with a Lego ruler. This extends my electroacoustic experiments. My final-year piece, The Cello That Didn’t Want to Die, already explored this: taking an instrument with a strong identity and deforming it into new sonic territory.

This exploration fascinates me. Classical music pushes boundaries, but instruments remain fixed. Recorded music, especially film music, opens endless possibilities: deforming, pitching, reversing, cutting sounds to create new worlds. Thomas Newman’s inventiveness in textures and instrumental combinations has been a major influence.

DR : I don’t know that film or composer, thank you for the reference. I love discovering new things, and I’ll gladly look into it.

Regarding Les Rivières Pourpres, I specifically wanted the cello sound to be unique. It needed to be somewhat “dirty,” crushed, rough, to match the series’ dark atmosphere. A lyrical approach simply wouldn’t have fit what I was looking for. I chose to treat the cello not merely as an instrument, but as a genuine sound material. For example, I sometimes struck the instrument to produce certain sounds, used the bow unconventionally, or even rubbed the strings with a Lego ruler. This extends my explorations in electroacoustic music.

My final-year piece, The Cello That Didn’t Want to Die, already laid the groundwork for this research: starting with an instrument with a strong sonic identity, then leading it into uncharted territory, ultimately deforming it to transcend its status as an instrument and conceive it as pure sound material.

This is a terrain of exploration that fascinates me. In classical music, much has already been written and pushed to extremes, yet instruments retain inherent limits. Recorded music, and particularly film music, opens infinite possibilities: you can deform, pitch-shift, reverse, or slice sounds, creating entirely new sonic worlds. This aspect of my work excites me greatly.

I have boundless admiration for John Williams, but I don’t feel inclined to write in a purely symphonic vein like him. What excites me more is working with smaller ensembles, where each soloist is identifiable, or blending ethnic instruments with a classical orchestra. I don’t use them to evoke geography; I’m interested in their singular timbre and expressive potential. I also enjoy exploring the meeting points of acoustic and experimental sounds, or inventing percussion from organic noises. In short, what stimulates me is this constant search for atypical textures, the desire to create sounds I haven’t yet heard elsewhere.

In this pursuit, Thomas Newman has been an enormous influence. His inventiveness in timbral exploration and instrumental combinations remains a precious source of inspiration.

DP: I greatly appreciate the clarity with which your instruments unfold, each identifiable by its timbre and interpretation. Do you consider this a musical signature, or rather one aspect among others of your

approach ?

DR: It’s something I developed gradually, almost unintentionally. I remember a Spanish journalist, Conrado Xalabarder, describing my work on Before Snowfall as a “grand chamber orchestra.” I found that description particularly accurate.

This type of orchestration, which is now part of what one could call my sonic signature, arose from several factors.

First, there was a very concrete reality: I rarely had the budget to record a full symphonic orchestra. I had to find compromises, mixing live strings with a small instrumental ensemble, complemented by synthetic elements. Reducing the string section immediately gives a color closer to chamber music than to a large symphony. So it was partly a budget-driven choice.

But there’s also an aesthetic dimension. I have absolute admiration for Ravel, whose orchestration I consider a model of perfection: every note naturally finds its place, each timbre stands out with absolute clarity. You hear everything. This precision, this transparency, deeply marked me. I find a similar approach in Steve Reich: his pieces rely on repetitive motifs that allow timbres and rhythmic interplay to emerge.

Thus, when I choose an instrument like a celesta, English horn, or clarinet, I want that timbre to be heard precisely. I don’t systematically double phrases to create a mass effect, as some composers like Hans Zimmer do. Instead, I prefer to assign a theme to a specific instrument without reinforcing it unnecessarily. This gives my writing the sound of an “expanded chamber orchestra,” where each instrument retains its personality.

Over time, I realized I was particularly comfortable in this aesthetic, which gradually became part of my style. I believe that with Before Snowfall, I truly found the sonic balance I was seeking, which I’ve continued to refine since. Of course, if I ever had the opportunity to write for a large symphonic orchestra with choir, I would gladly do so. But I remain attached to smaller ensembles. I’ve even designed two cinema concerts in formats of ten to fifteen musicians, all soloists. This choice seems faithful to my writing style, and also pedagogically valuable: when children attend the concert, they can immediately identify the instrument they hear (clarinet, oboe, etc.) without it blending into a section.

Ultimately, I am deeply attached to the uniqueness of timbres. Each instrument is unique, and my joy as a composer is to highlight them as solo voices.

DP: I find your musical ideas very perceptible: your music is rich, nuanced, inventive, yet never gratuitous.

Even in more experimental passages, one feels that every choice, every chord, every orchestration, every modulation responds to a precise intention. Nothing seems left to chance, and everything appears to move in a clear direction. Is this coherence and legibility something you consciously strive for? Does ensuring that the audience understands your music matter to you ?

DR: Thank you for the compliment. I’m glad you noticed, because it’s indeed an obsession in my work: I want everything to have meaning, nothing to be gratuitous. To me, if music is placed on a scene, it must contribute something; otherwise, it’s better not to include it. Whenever I decide otherwise, I always ask myself: why here? What does it convey? What does it truly add? Every choice—instrument, harmony, synchronization—must be justified. Even if that justification exists only in my head, it serves as a guide.

This likely comes from my filmmaking background: I believe no element in a film should be left to chance. A fully successful film score, for me, is one that exists as an autonomous work yet, projected on images, makes complete sense because it is in total symbiosis with the film—through timing and intent.

I constantly ask: why place music here? Why choose this instrument? What does it evoke? Why synchronize precisely here and not elsewhere? This rigor may seem obsessive, but it makes this work fascinating. It forces me to immerse myself deeply in the film, its narrative, its emotions, so that the music is not mere highlighting but a true character, able to impact both viscerally and intellectually.

What I hope is that, over the years, when revisiting the film, this music remains relevant, continuing to dialogue with the image as intensely as at release. That’s why I was deeply honored when a young musicologist, Manon Léger, devoted three years of research to my work on Les Rivières Pourpres. It proves that there is substance to analyze, and that is perhaps the greatest compliment one can give me.

DR: I think AI will indeed make certain types of compositions—and the composers associated with them—disappear. Take, for example, cooking shows or fashion magazines. They often use background music: short, interchangeable pieces selected to color an atmosphere without real artistic significance. In that context, producers will no longer need a composer; they will rely on ready-made sound libraries, with “fun,” “dramatic,” or “suspenseful” music. The quality doesn’t matter much, because these tracks are brief and rarely listened to attentively. From their perspective, it saves time and money. In a sense, AI will replace the existing music libraries.

But this precisely underscores, in my view, the importance of the composer’s role. Hiring a musician rather than a machine is about everything an algorithm cannot provide: a unique vision for the film, inventive choices that step outside established formats, a human dialogue with the director, and a sensitive, original reading of the images. And, of course, the beauty of working with real musicians—the living interpretation that nothing can replicate.

So it’s not a matter of fearing technology; it will continue to evolve, whether we like it or not. It’s better to observe it, understand it, see how it can enrich our tools, while reaffirming what is irreplaceable in our profession: creativity, unpredictability, and the human connection.

DP: You have a solid training in music and composition, which is evident in your work. Yet, as you know as well as I do, film music still struggles to claim its full value and existence, especially in France. I’m certain that had you worked in the 2000s, you would have been overwhelmed with opportunities, because film music then had a more prominent role. In today’s industry, the pursuit of cost savings too often relegates music to a secondary component. We can see it clearly: most compositions are now done on computers, due to a lack of budget for a real orchestra.

Even with your refined creativity and unique musical approach, do you think producers and directors—facing tight budgets, will still recognize the human touch of a composer as opposed to a sound designer using AI to produce a cheaper portion of the score ?

D.R.: I don’t believe the key question is distinguishing AI from humans. The real issue is what you want to convey. There have always been composers working with electronics: listening to Vangelis or Éric Serra on their synthesizers, you immediately perceive the presence of a creator, a sensibility. In other words, the challenge isn’t the technology itself, but the relationship you establish with the composer—the dialogue, the exchange of ideas, the building of a shared vision. That human connection cannot be replaced, and I hope it will continue to be valued. As for budget cuts, they are very real and increasingly severe, but this issue goes far beyond music.

DP: Are young directors or producers still genuinely interested in high-quality film music, or do they now see it as an accessory, too costly to justify ?

Can you outline their profiles: do they have real musical culture to argue for their choices, or is their approach limited, shaped by budget constraints and differing creative priorities ?

DR: I’m rather optimistic about the new generation. When I studied cinema, film music was often seen as “artificial emotion” to be avoided. The Dardenne brothers had just won the Palme d’Or for Rosetta, and a certain critical current believed that a “great film” should be music-free. For someone dreaming of composing for film, that wasn’t very encouraging.

Today, the young directors I meet—often on their first or second feature—grew up with Steven Spielberg and John Williams, with Robert Zemeckis and Alan Silvestri. They were nurtured from childhood by films that gave music a real place, often symphonic. These references are part of their cinephile DNA, making them much more attentive to music than their predecessors. I hope this trend continues.

That said, mixing remains a major challenge. In France, realism is traditionally prioritized: every sound must be heard, even a pigeon three streets away. Music is often relegated to the background, whereas in the U.S., it is highlighted, sometimes at the expense of other sounds. This difference reflects cultural priorities: France, more literary than musical, still often treats music as mere accompaniment rather than as a true character of the film. Much remains to evolve on this front.

DP: In an online interview for La Maison du Film, you mentioned the importance of dialogue with the director and the search for a “pseudo-sonic semantics” to understand what needs to be done while responding to their requirements. Do producers still interfere in musical choices, or is it now mostly between you and the director ?

DR: In France, collaboration is usually built directly with the director. This is a notable difference from the U.S., where composers are sometimes treated as technicians, and producers often have decisive influence. It depends on the project: a cinema film, typically conceived and led by an auteur director, functions differently from a TV series, more closely supervised by producers and showrunners.

Most often, my primary contact is the director. Other voices, especially producers, intervene legitimately since they fund the project. But for smooth workflow, it’s best to centralize feedback with one person, usually the director, who becomes the spokesperson for the team.

I’ve faced more complex situations—for example, on Enquêtes extraordinaires, where over ten people provided input. That can quickly become hard to manage. Conversely, when the director fully embraces the role of mediator, collaboration is much more effective. After all, they carry the film, have the vision, and are often also the screenwriter. As composers, our role is to accompany them, helping bring their work to life with a musical dimension aligned with their vision.

DP: During your training, you studied at Pierre Schaeffer’s GRM, a reference linked to Le Club d’Essai. What did you learn there, and how did it influence your approach to sound composition ? Like François de Roubaix or Morricone’s experimental group "Les Nouvelles Consonances" in the 70s, do you work on sound experiments to create a catalog of effects ?

Do sound effects and instrumental manipulations play a particular role in your creative process ?

DR : After graduating with a film music degree from the École Normale Alfred Cortot (unanimous honors), I pursued a year in electroacoustics. I wanted to experience the inverse of my classical training: to create music without instruments, treating every sound as a material to deform, transform, and sculpt, exploring how it could generate atmosphere or musical discourse. Coming from a very traditional background, I saw this as a way to expand my palette into a radically different language.

The impulse came after discovering Dancer in the Dark, where Björk’s music profoundly impressed me: she creates songs from real sounds that gradually transform into rhythms and form the basis of the composition. I thought: “I can write symphonic parts, but how can I achieve this electronic dimension?” In 2004, electronic music classes were not as developed, and electroacoustics was closest to what I was seeking.

It was a fascinating experience: electroacoustic composers operated in a world very far from mine, making for almost lunar exchanges, yet always stimulating. I was fortunate to work with passionate teachers like Régis Renouard-Larivière and Christian Éloy, and my final-year piece was even broadcast on Radio France. While I did not continue in that radical style, all current sound manipulation in my work stems directly from that formative experience.

I still write purely classical pieces outside of film work, but I never compose autonomous electroacoustic music. I do preserve all my experiments, forming a personal sound library I draw from regularly. These textures, shaped by me, create a unique sonic color, contributing to what people call my “style.” Whenever I explore this path, it directly responds to the film: the images themselves—gravel, a passing train, cracking wood—spark these manipulations.

My ear is always alert. If I hear an interesting sound in daily life, I immediately record it on my phone for future use. This habit comes directly from my electroacoustics years: they taught me to listen to the world differently, perceiving musical potential in everyday sounds. With perfect pitch, I instantly recognize the pitch of a sound, which often inspires me to work it into my film compositions.

DP: If you were asked to create a more visceral or cerebral music, by reflex, would you turn to noise-based creations (like Luc Ferrari, for example), or to dissonant works and experimental compositions by avant-garde composers such as Penderecki, Tristan Murail, or Steve Reich ?

Or do you adopt other creative strategies, pushing yourself to explore differently and sometimes keeping at a distance from the influence of these references

?

How is this approach organized in your composition process, and to what extent does the search for new forms of musical expression push you to explore territories that escape preexisting influences ?

DR: Generally speaking, I don’t forbid myself anything. At first, I was afraid of unintentionally plagiarizing, since I’m nourished by so many different types of music, as any composer is, ultimately. But after all, there are only twelve notes… So I decided to trust my instinct and my musical memory: if something sounds too obvious or too close to an existing work, I sense it immediately. For everything else, I let myself be guided by feeling.

Steve Reich had a decisive influence on my writing, as much as Ravel. My taste for rhythmic and timbral games, for loops that are never quite loops, clearly comes from him. But I believe I have integrated this influence along with others, whether near or far, so that what I compose today is the fruit of this digestion.

That said, I have always wanted acoustics to remain at the heart of my work. I would not spontaneously turn to a noise-based aesthetic: I love melody, harmony, and orchestration too much. Thus, for Derrière les murs, I preferred an approach close to Ligeti, exploring how he decomposes the orchestra. For example, by dividing the strings into about forty voices separated by semitones, rather than using electroacoustic treatment.

DP: You haven’t yet experimented with a fully synthesizer-based score, like Maurice Jarre or Jerry Goldsmith did. If the opportunity arose, would you be interested in such an exercise ?

DR: When I work on some TV documentaries without a budget for recording, I do compose entirely with synthesizers. Simply, I don’t use them with the typical ’80s sounds, as Goldsmith or Jarre might have. That said, I am never truly satisfied when I have to write a soundtrack purely in synthesis. I love real instruments too much, and the total absence of their presence in a film score always feels a bit unfortunate.

DP: Among cinematic genres you haven’t yet explored, which attracts you most as a composer ?

DP: I like almost all genres because what excites me in this profession is being able to move from one universe to another. My dream, however, remains composing for an animated feature, because that’s where I feel the most in alignment. There are also genres I haven’t yet explored, like science fiction or musicals. But more than a particular style, what drives me is each new project, as it represents an adventure, a meeting, a story to tell.

I haven’t yet found the “lifelong partner” that Serra had with Besson or Williams with Spielberg, but that is something I would very much like. A director who trusts me film after film, with whom we can mutually encourage each other to go further, experiment, and surprise ourselves. Over time, such collaboration allows for greater daring: the director learns to give more space to music, while the composer gains confidence and explores new paths. After all, no director wants to make the same film ten times, and it’s the same for us composers. We can change universes without changing partners. It is in this reciprocal trust that the most beautiful scores are, I believe, born.

DP: Imagine being offered to compose the score for Tron Legacy at Disney. Would you approach the project by respecting your personal style while adapting to the film, or would you try to break from your habits to explore a new musical universe ?

DR: I am eagerly awaiting the release of Tron: Ares, as the Tron universe has always fascinated me. If I were ever approached for such a project, my first question would concern the reason for this choice: would it be to find certain colors inherent to my writing, perceived in my previous work, similar to Éric Serra when he was called for GoldenEye, or would my presence result from another context, such as a co-production, implying a necessary adaptation to the existing universe? If, however, I were entrusted with the project, I would necessarily see it as an echo of something in my music that had caught their attention. My first task would then be to identify this unique element in order to preserve it, while taking on an exciting challenge: to integrate into an already established universe while leaving my own signature. This is precisely the same question faced by composers called to succeed John Williams in the Harry Potter saga: how to reconcile respect for the legacy with asserting a new voice? An intimidating exercise, but deeply stimulating.

In the case of Tron, it would be obvious to invoke electronic, metallic, cold sounds, as the visual universe itself imposes this climate: the bikes racing at full speed, the luminous lines, the dark, almost video game-like digital aesthetic naturally call for such a palette. The imprint left by Daft Punk in Tron: Legacy is such that it would be necessary to refer to it, without reproducing the motifs, but rather by extending the spirit. I would seek to explore synthetic textures while enriching them with a more organic dimension, perhaps by overlaying the expressive depth of a cello.

DP: On a day off, if you could immerse yourself in three classical works of your choice, which would you pick and why ?

DR: It depends on my state of mind. If I want to be surprised, I prefer to pick three discs at random from my collection and listen without preconceptions, simply for the joy of discovery. Perhaps an aesthetic shock will occur, perhaps not, but in any case, I will have nourished my curiosity, and I deeply enjoy that moment of confronting the unknown.

On the other hand, if the desire is to revisit works that have accompanied me for a long time, like meeting a faithful friend, then I turn to three pieces that are essential to me: Daphnis et Chloé by Ravel, The Planets by Holst, which seems to me a true “Bible” for any film composer, as everything is already contained there, and a work by Steve Reich. I would probably choose Music for Large Ensemble, which seems to me one of his most successful, like a more compact but equally powerful version of Music for 18 Musicians.

And of course, I wouldn’t just listen: I would also study the scores, because I greatly enjoy reading them for pleasure, as another way to rediscover the music.

DP: Imagine a long six-month stay in space: you can only take three film music CDs. Which works would you choose and why ?

DR: Since it’s a trip into space, I must admit I would love to take three box sets, like those sometimes available for cinema: the complete John Williams collection or the complete Michel Legrand collection… Or even better: the Best of Vladimir Cosma box set, with a hundred CDs, enough to last the whole journey !

Joking aside, if I had to truly limit myself, I know I never tire of listening to Lemony Snicket by Thomas Newman, Léon by Éric Serra, and A.I. Artificial Intelligence by John Williams. Three very different universes, but each, in its own way, moves me profoundly.

That said, three discs are really quite short… Deep down, I wouldn’t be able to limit myself: I would take my iPod, overflowing with music, so I would never run out of notes.

DP: Which composer from Hollywood’s Golden Age do you prefer, and which of their works impressed you the most ?

DR: Inevitably, John Williams—he is God for me. You find absolutely everything in his work: he wrote the greatest themes in cinema history, explored every genre, and his orchestration skills are exceptional. But beyond this mastery, it is above all a profound humanity that you feel in his music. Even in his most complex works, his writing remains clear, readable, immediately accessible. And he has continually renewed himself, adapting to each project. Between Star Wars and Memoirs of a Geisha, the contrast is striking. For me, he remains the greatest, and meeting him was an absolute dream. When that moment arrived, I was literally on a little cloud, and physically I felt tiny in front of him.

Apart from Williams, I am fascinated by Jerry Goldsmith’s rhythmic science, whom I consider the second great composer of the Golden Age. His way of composing with syncopated and asymmetric rhythms, always perfectly controlled, allowed him to land naturally on the points of synchronization: in my eyes, he is Stravinsky’s direct heir. I also admire Elmer Bernstein, notably for The Ten Commandments and The Magnificent Seven, without forgetting the fundamental contributions of Max Steiner, Lalo Schifrin, and Alfred Newman.

I would also like to pay tribute to the composers who shaped the Disney universe: the Sherman brothers, Oliver Wallace, George Bruns, and of course Alan Menken. The latter, for me, represents the second Golden Age of Disney, and his work deeply influenced me. The Hunchback of Notre-Dame album was a decisive influence.

But well… John Williams is God.

DP: Among film composers, who surprises you the most with their style or technique ?

DR: I feel like mentioning Thomas Newman, because he is probably the one whose sound creations surprise and intrigue me the most. Every time I hear one of his scores, I want to understand how he built his arrangements, how he shaped those unique textures. I know that with each new film, there will be something atypical: his signature is immediately recognizable, yet he always manages to reinvent himself and go where one does not expect.

What fascinates me in particular is the way he considers the relationship between music and image: rarely does he simply accompany the scene at face value. On the contrary, he offers a skewed, often unexpected reading, which enriches and transforms our perception of the film.

In short, he is a composer I listen to with my eyes closed, no matter the project. Among the composers I dream of meeting, he is probably the last one I have yet to encounter. Talking with him must be fascinating, and I am convinced I would learn an enormous amount from such an exchange.

DP : In your composition process, when do you approach the creation of the main theme: as soon as you read the script, during the rough cut, or after exploring the entire sound universe? Could you illustrate your answer with specific examples ?

DR: Generally, the film’s theme is the first thing I look for. So I start writing it as soon as I’m involved with the project. This can happen as early as the script stage, though that’s fairly rare. For example, with Derrière les murs, the main theme—the one heard in the end credits—was born from reading the script and the distress of the woman who had lost her daughter.

If I am brought in during the first cut, I like to watch the images first to absorb them, then step away from the computer: go for a walk, do something else, let my mind wander. After a while, a melody starts looping in my head, and it is often this one that I retain. I trust my subconscious a lot: the first idea is very often the right one. Or at least, it contains something that will persist until the end because it arose from an instinctive impulse, free of conscious thought. This was the case for L’Odyssée de Choum: after seeing a sequence being animated by the director, I went home, and during the night the main theme imposed itself. The next day, I developed it into seven different versions to show how it could adapt to all situations in the film.

If I am contacted at the end of production, once the cut is locked and generally already temp-tracked (i.e., covered with temporary music integrated into the final edit), I first request a version without that music. This allows me to discover the film in a pristine state and create a theme directly inspired by the images, without being influenced by the temporary tracks already present. Only then do I analyze the temporary music chosen by the team, to understand what they were trying to convey, which can indirectly inform my own work.

In any case, I always start by finding the theme and then its harmonization. For me, this is the backbone, the DNA of the film, the foundation I constantly refer back to. And whenever I feel lost in a scene, I return to the fundamentals: what is the theme, why is it that one, and what does it say about the film?

DP: Considering one of your works, Lettres ouvertes. It features a very reduced instrumentation, a small ensemble accompanied by your electronic or computer interventions.

Was this a budget-driven choice or a conscious artistic decision ?

DR: As often, it was a combination of both. I knew there wasn’t much budget, so I didn’t plan to write for a full orchestra, but rather for a small ensemble. Keeping this constraint in mind, I make artistic choices so that each instrument feels purposeful—not due to lack of means, but because it’s the aesthetic choice best suited to the film.

For Lettres ouvertes, this choice proved very pertinent. The strings convey both the emotions of the seasonal workers (between melancholy and determination) and support staccato loops symbolizing their progress despite difficulties. The sound of a small string ensemble, rather than a full symphony orchestra, brings intimacy that fits the subject well, as these are letters read by the descendants. Additionally, I could play with harmonic textures to reflect the fragility of their situation, expressing the full emotional palette of the project with a limited but sufficient ensemble.

The director herself had very fitting words about the soundtrack, capturing what I wanted to convey:

"David was able to convey through music the precarious status of having a residence permit in Switzerland, the race to obtain a more ‘stable’ permit or reunite with family when possible. There’s also the sadness of that era experienced by seasonal workers and their children, felt in the music without victimizing them. Bravo, David!"

Incidentally, I was very happy to work on this film because Katharine Dominicé and I studied film together; we graduated from IAD in 2003. It was really nice to reconnect twenty years later to score her feature film!

DP : Do you enjoy composing under constraints—time, budget, format—or do you prefer total freedom ?

Have these restrictions ever pushed you to explore unexpected paths ?

DR: Constraints are part of the job. When making film music, you know there are frameworks: deadlines, the fact that your music will be mixed with other sound tracks, etc. Above all, you work for a film—for a director, producers, editors… You are part of the film’s universe; you are not composing purely freely. But if I chose this profession, it’s precisely for that: the director invites me into their universe, I bring mine, and together we create a new shared world.

Through a film, I can explore things I wouldn’t have done otherwise: atonal music with Derrière les murs, ethnic music with Min Ye or Before Snowfall, etc. I like these constraints, especially as I work well under pressure. My brain starts searching in all directions when it knows it has to produce quickly, and I’ve learned to use these constraints as real assets—or even as powerful inspiration boosters.

DP: What I particularly appreciate about your music is that it avoids the need to be linked to a big name in the field. This is striking today, in a context saturated with references and codes already deeply ingrained in our sonic imagination. With you, one perceives a clear attention to uniqueness, a desire to preserve a personal signature. After all, what would be the point of reproducing what has already been heard a thousand times ?

This concern for uniqueness is all the more remarkable today as many young composers (often constrained or influenced) create music that is highly marked, sometimes imitative. Of course, within a film context, the composer does not always have total freedom: they must compose considering the director’s desires, who remains the dominant voice.

Even among renowned composers, one can sometimes perceive works where influences blend too noticeably: a bit of Williams, a bit of Poledouris, Goldsmith, or Philip Glass, to the point that their personal voice is diluted. It’s also tempting—or easier—to lean on an already codified sonic universe, especially in very structured genres. Consider Elmer Bernstein, for example, a benchmark for the Western.

This is precisely what makes your work, for example on L’Odyssée de Choum, remarkable: you avoided the trap of stereotypical music or a simple “in the style of.” The absence of references allows a full focus on the writing itself, on what it tells, within its own logic.

With you, a strong personality emerges through your choices, the clarity of your orchestrations, and the sensitivity you give to certain instruments, especially the previously mentioned cello. Except for the way you develop certain rhythmic modules—which can remind one of Thomas Newman—no direct comparison comes to mind when listening to you. Except when you deliberately offer one as a nod, such as with James Horner’s Zorro, which you have already mentioned.

DP :Do you agree with this reading ?

DR: First of all, thank you, that’s really kind. Since I listen to a lot of film music, I’ve always been a little afraid that people might notice unintended influences or similarities that could be mistaken for plagiarism. I have, however, consciously made nods or even offered temporary music to a director. For instance, for Facteur chance, I mentioned Zorro and also proposed John Powell’s Mr. & Mrs. Smith to the director because I thought the music fit the script perfectly. As he also liked Powell, we went with that idea, and my music became a deliberate nod. Especially as it was my first TV film, I had even less experience than today.

For L’Odyssée de Choum, I knew what temporary music Claire Paoletti and Julien Bisaro had used. But I found the theme independently of all that, as I explained, after seeing a sequence in their office while it was being animated. Finding the theme detached from any pre-existing music probably helped on this film, because it became my foundation: I could always rely on it. When they sent me a scene with temporary music, I could easily remove it and go back to my own feeling. Since I was involved in the film from the beginning, they quickly abandoned the temporary music and used my sketches, which allowed a score with its own singularity—even if some people mentioned the Zelda theme, which is funny because I hadn’t played Zelda at the time.

As for Thomas Newman… as I said, he is a model for me. Sometimes I try to explore certain ways of arranging music like him, making textures resonate with a particular style of reverb or delay because his sound resonates deeply within me.

If you feel I have enough personality not to be simply tied to another name, that touches me a lot. I hope one day people will say: “That’s Reyes,” not “a Newman wannabe.” What will make my signature recognizable? Honestly, I don’t know: it’s mainly those who listen who will tell… or those who take the time to analyze, like my musicologist partner.

DP: To continue our reflection and provide some context, I would rather situate you not in terms of style, but generationally. In the quite organic way you integrate music into the film—especially with attention to story, rhythm, and space—I would almost call you the “spiritual son” of Bruno Coulais, but with your own well-defined personality.

It’s not a question of direct influence or stylistic resemblance, but rather a closeness in how music serves the image and narrative while retaining a true sonic poetry.

DP: Do you accept this reading ?

D.R.: Again, thank you. I have enormous admiration for Bruno’s work, and I also greatly appreciate him as a human being. I even asked him to be the godfather of the second edition of the No Limit Festival in March 2026, which I organized in Strasbourg… It’s a way to pay tribute and acknowledge his influence on my journey.

There are some amusing coincidences in our paths: we both worked on a Souleymane Cissé film as well as Les Rivières Pourpres—he on the movie, me on the series.

I also have a memorable anecdote: Bruno was the first composer to invite me to a recording session. He was working on La Planète Blanche, and thanks to Laurent Petitgirard, the conductor, I could observe a recording day. I saw Bruno working with the orchestra, with voices, and orchestrating organic percussion, notably rhythms based on stones… At the end, very shy, I gave him my Microcosmos album for his signature. He wrote: “To a future colleague, best wishes.” That deeply affected me: if he thinks I can become his colleague… then I can really achieve it. That’s also Bruno: his kindness. Musically, we share a similar approach to film music: it’s not there to repeat what’s on screen, but to offer another reading, acting as a third character, inventing instrumentation that gives the audience a unique and unexpected journey.

Microcosmos was one of the first scores that deeply impressed me as a young person, notably the bee sequence, where Bruno breaks the boundary between music and sound, with violins evoking wing beats echoing Laurent Quaglio’s sound design…

Yet I worked to digest his influence to find my own uniqueness, and I think when one hears my work on Les Rivières Pourpres, one does not think of Bruno’s film music.

DP: We’ve discussed your uniqueness and possible musical lineages, but one score in your career has particularly struck me and remains among my favorites: Behind the Walls (Derrière les Murs). It’s a score I greatly admire, yet I would describe it as more “Americanized.” From the opening credits, I sensed an atmosphere reminiscent of works like Alien or Outland: a dark, almost metallic theme, with a “ferrous” string layer, very tense, almost spectral.

This score has something profoundly cinematic, in the Hollywood sense, but also a complete mastery of contained, mysterious tension that truly fascinated me. Moreover, there’s the superb love theme and Valentine’s theme, which reminded me of other musical worlds I greatly admire, such as Christopher Young or Jacob Groth in Millennium. It’s interesting because even if certain sounds can be linked to familiar references, it’s not something you can fully control: it’s our emotional references that act in this way. This musical and sonic culture is deeply embedded in us, always connecting us to what we hear at the deepest level.

With the entire historical backdrop of film music—from the Golden Age to the Silver Age, through the Nouvelle Vague, up to what some now call the “Bronze Age” or “era of connected creation”—how do you navigate between the heritage of highly codified film music, with its major classics and essential references, and the need to renew yourself in a context where technology and production methods have radically transformed the sonic approach? In such a rich and dense musical universe, how do you preserve the originality of your writing while avoiding unconscious influences from works you’ve already heard ?

DR: Actually, I sometimes try to navigate off the beaten path… but above all, I try to move forward without being influenced by everything that’s been done before. Music already exists; it permeates us, and everyone has their own references, so everyone links what they do to what they love or what has shaped them. But your references are not necessarily mine… and that’s also the beauty of music: it’s a very personal journey.

I am a huge consumer of film music; I listen to it every day, and since early childhood I have collected records and scores, and I watch a lot of films to observe what is being done… I love it. But when I compose, I try not to be crushed by the weight of references: neither those that came before me, nor those of my talented colleagues, whose work I admire. My goal is simply to chart my own path, always returning to the essential: the film, nothing but the film. I am given a story, and I seek to translate it through my own language: this is my only direction, my fundamental guide.

This was also the message I conveyed to my students when I taught film music courses: always start from the image, the story, what needs to be translated. Some colleagues would have their students copy almost exactly pages from James Newton Howard. Personally, I see no point: how can a composer forge their own identity if, from the start of their studies, they are asked to copy someone else’s work? In my courses, I would give a blank sequence, letting the students freely compose after a brief on the scene’s intentions. Once the first mock-up was submitted, we would debate, analyze, discuss: what had they expressed, why did it work or not, how could it be improved… But everything had to start from their initial version, not from a reference.

I apply exactly the same principle to my own work: I draw from deep within myself what the film evokes emotionally. To do this, I try to get into the mindset of the sequence (if it’s dramatic, I put myself in a sad state) and translate it into music as accurately as possible, so the audience feels what I myself experienced.

For example, in Behind the Walls, the references we discussed were those of Ligeti, particularly as Kubrick used them in 2001: A Space Odyssey or The Shining. I purchased the Atmosphères score to dissect its orchestration. For films like Alien or Outland, I didn’t have the scores in mind at the time, but I recently rewatched Alien and immersed myself in its absolutely incredible music. Whereas we were discussing synths for Gremlins, in this score, all the sounds evoking space or the creature were created from unusual organic instruments:

The main strength of Alien’s score lies first in the sonic illustration the composer offers on screen, achieved through the use of rare and diverse instruments, revealing a true musicological work. Among these exotic instruments, atypical for a late-1970s Hollywood film, are the serpent (a six-hole horn with a key system and an ivory or horn mouthpiece, widely used in late 16th–early 17th century religious music), two conches—one Indian, one Polynesian—used to create unique sounds, a shawm (a double-reed woodwind of the oboe family, common in the Middle Ages and Renaissance), a didgeridoo (a wind instrument used by Aboriginal Australians, made from a termite-hollowed eucalyptus branch, electronically processed by Goldsmith to produce a strange, viscous, slime-like sound totally inseparable from the alien in the film), not to mention the Echoplex effects the composer had already experimented with in 1968 on Planet of the Apes and in 1970 on Patton with his famous trumpet echoes. 1

I find this work simply extraordinary.

Regarding Valentine’s theme in Behind the Walls, it was a film where I was contacted from the script stage. The theme emerged very quickly: it evoked Valentine in the film, but by the end, you realize it also references Suzanne’s missing daughter. It was a red thread from the opening credits, subtly over the images of the car arriving at the house, creating an ambiguity that allowed the horror to gradually set in. The producers, however, thought it wasn’t scary enough and requested a more explicit opening, in the spirit of The Shining, to immediately signal that the film would be a suspense thriller. It’s the same logic as Goldsmith’s work on Alien: his first version was rather romantic to evoke the beauty of space, but Ridley Scott wanted the music to instill anxiety right away.

DP: How do you perceive the score for Behind the Walls today in your career ?

Is it a stylistic exception, or a facet of yourself that you would like to continue exploring ?

DR: I actually recently rewatched it and I think the film has aged quite well. What surprises me is that this score continues to be mentioned by many, even though the film didn’t achieve the expected success in France, whereas in China and Russia it was a hit and reached the top five.

What I love about this score is primarily the beautiful lyrical theme, with the violins as I like them, which I could really develop in the closing credits. But there is also, throughout the first part, the immense challenge of writing atonal music, an exercise I had never tackled before, which pushed me to explore completely new directions. In hindsight, I’m happy to see I handled it fairly well.

The Macedonian orchestra that recorded the score actually hated me at times because playing such tense, slow music, with long passages and many harmonics, demanded enormous concentration. But that tension felt by the musicians served the music: it nourished the atmosphere I was trying to create. And it’s funny because they still talk to me about it today, even though it’s already been fifteen years!

In short, all this to say that it’s a film I still love very much. Even if the ending is slightly weaker, I find it overall very successful: the sets and costumes are convincing, Laetitia Casta acts very well, and the music has a good place and is rather well mixed. So I can sleep peacefully thinking about this work.

DP: Are you more attracted to the opportunity to write a score like Open Letters (Lettres ouvertes), with its intimate, minimal, and personal approach, or a project like Behind the Walls, where you explore more tense, spectral, perhaps even more “Hollywoodian” atmospheres ?

Do you prefer moments when you can explore your own voice, or do you also appreciate the freedom a slightly more “conventional” sonic work can offer, like The Fox and the Child ?

DR: The common point between these two films is the use of a string orchestra… but exploited very differently. In Open Letters, the orchestra is smaller and recorded very closely, giving a more intimate, closer sound. In Behind the Walls, on the other hand, the orchestra is larger and recorded in a big studio, which allowed for a more expansive, more “Hollywoodian” sound, creating an enveloping, oppressive, tense atmosphere.

Looking at these two examples, you can see that you enjoy my way of working with strings! That said, I miss a film like The Fox and the Child. I love writing for films aimed at children or general audiences, with beautiful orchestras; that’s also why animated films fascinate me. Even though I enjoy writing for orchestra, I always try to highlight soloists and integrate instruments that don’t necessarily belong to the traditional classical orchestra. The more different timbres I have at my disposal, the happier I am. I’m a philatelist of music!

ML: Once the last note is written, it’s time to record the music, whether to accompany the film or to create standalone versions for CD or streaming platforms like Spotify, Deezer, or Apple Music. When conditions allow, as with The Odyssey of Choum (L’Odyssée de Choum) or The Fox and the Child, the production provides you with a group of instrumentalists. In this context, do you conduct the orchestra yourself, or do you prefer to entrust that responsibility to a professional conductor?

DR: The ultimate goal for a composer remains to record their music with real musicians. And, in this case, the ultimate grail is conducting your own score yourself, like you see in the making-ofs of John Williams or Alexandre Desplat. Unfortunately, in reality, that’s not always possible.

For my part, I would like to conduct my music systematically. On one hand, because communication with the musicians would be more direct (I know what I wrote and can correct immediately), and on the other, because conducting is a true pleasure. Since childhood, I’ve nurtured this dream: I used to put records on in my room, a score on a stand, and conduct into the void as if I were already in front of an orchestra.

In practice, recordings sometimes take place abroad, in Bulgaria or Macedonia, for production reasons. In these cases, a local conductor leads, while we follow the session from the control room, giving instructions in English. When I work with the excellent musicians of Strasbourg, they are usually accompanied by their designated conductor. I then find myself again in the control room, adjusting after each take. This collaboration works very well, but I must admit a slight frustration: I would like to be more often at the podium, with my assistant in the control room indicating what needs to be redone.

I’ve had the opportunity to conduct several times: twice my own music during recordings in Belgium with a “phone” orchestra for The Odyssey of Choum and A Song for My Mother. Once for a friend and colleague, Selma Mutal, who entrusted me with conducting her musicians in Barcelona for her first film, Madeinusa (2005).

I hope in the future to wield the baton more and more often, and perhaps even conduct my own concerts. For me, it is the ultimate reward after all this work: hearing your notes come to life under your own direction is an absolutely unique experience.

[1] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alien_(bande_originale)

Propos recueillis par Pascal Dupont - Cinescores Center - Photo ci-dessous - Sophie Chamoux - DR - Photo haut - Collection David Reyes