Franz Waxman

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.21 / No.82 / 2002

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven and Dirk Wickenden

I would like to thank John Waxman for being so willing to answer my array of questions, as well as offering his advice and constructive criticism of my article. Franz Waxman photos are courtesy of John Waxman. Please visit the Franz Waxman website, which also features a link to the Waxman papers at Syracuse University.

Franz Waxman is an important figure in the annals of motion picture music. His special brand of music, composition, particularly his film music, has influenced many subsequent film composers, including Jerry Goldsmith, who began his career while Waxman was still scoring films and who today is considered an influence on many new composers himself. With the assistance of the composer’s son John, himself a prominent figure in movie music (but for different reasons) we present an appreciation of a talented composer who was equally at home writing movie and concert hall music.

As is well documented, Hollywood was founded by Jewish immigrants, who set about making “an empire of their own”, and it is still curious to think that what is seen as a purely American institution was founded by those not hailing from the “land of the free”. This of course extended through all elements of filmmaking, including the music. It was these émigré composers, both Jewish and gentile, many fleeing the tyranny of Nazi Germany, who created what we know of as the “Hollywood Sound”.

Beginnings - One such composer was Franz Waxman (original spelling Wachsmann), born on Christmas Eve 1906 and hailing from Königshütte, Germany (now Chorzow, Poland). Many film music publications state he was the youngest of seven children; in fact, the Wachsmanns had eight including Franz, the others being: Paul (1895-1982), Elfriede (Frieda) (1896-1988), Fritz (1897-1945), Max (1898-1918), Dorothea (1902-1903), Ernst (1904-1966) and Alfred (1905-1906). Young Franz showed skill at the piano and also at composition but his father, who was a salesman in the steel industry, did not encourage him and when he was sixteen, he became a bank teller. His earnings went towards paying for instruction in piano, composition and harmony. Two and a half years later, he enrolled in the Dresden Music Academy and also journeyed to Berlin in 1923 to study composition and conducting at the Berlin Conservatory. He supported himself by playing in cafes and was then offered a job arranging and playing piano in a jazz band named the Weintraub Syncopaters (a name which gave Waxman’s later friend and colleague, David Raksin, a great deal of fun to rib him about). Through this, he met Friedrich Hollaender (who himself would alter his name, to Frederick Hollander when he “went Hollywood”), who fuelled his interest in “serious” music and in turn, introduced him to Bruno Walter, with whom he studied. Walter also played an important part in Miklos Rozsa’s concert hall career.

Euro-Cinema and Hollywood Calling - Subsequently, Hollaender recommended Waxman to UFA producer Erich Pommer as an orchestrator and conductor. One of his earliest jobs (without screen credit) was arranging Hollaender’s music for the Marlene Dietrich starrer, Josef von Sternberg-helmed THE BLUE ANGEL (1930). However, after being beaten by Hitlerites, Waxman fled with his wife-to-be Alice to Paris. It was there that Waxman composed his first dramatic score for 1933s LILIOM, based, as was the 1956 American musical CAROUSEL, on Ferenc Molnar’s ‘Liliom’ and directed by Fritz Lang, in which the composer utilized three ondes martenot. Their use represented one of the earliest examples of electronics in film, gaining him more recognition. A move to America was prompted when Waxman was hired as music director on Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II’s MUSIC IN THE AIR (1934), as envisaged by Pommer, who, along with former UFA colleagues such as Billy Wilder and Peter Lorre, had preceded Waxman to Hollywood. Europe’s loss was Hollywood’s gain. Franz Waxman married Alice in Los Angeles on the 23rd June 1934. She was born Alice Pauline Schachmann on the 13th May 1905 and her first husband was Dr. Alfred Apfel, a lawyer and writer, who died in 1940. Waxman then became acquainted with another bride, this time of the fictional kind.

Director James Whale, an admirer of Waxman’s LILIOM music, invited the composer to score his new film, THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935). The result was one of the most revered scores in movie history. It is fair to say that its impact was the same as that achieved by Max Steiner’s KING KONG two years beforehand, and it is worth noting that both were of the same film genre. Universal used parts of Waxman’s score as stock music in other productions, for example the Flash Gordon serials starring Larry ‘Buster’ Crabbe and this helped the music achieve more recognition. Its presence is even felt in 1998s SMALL SOLDIERS, for the scenes of the girl’s dolls being implanted with microchips by Major Chip Hazard and his men. Waxman’s siren song-like theme for the Bride is used here – although only film music aficionados got the joke. Following his work on THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN, Franz Waxman became music director of Universal, a post presumably offered to him by impressed studio heads. As head of music, he continued to write scores.

Another important lady in Waxman’s life was Lella Simone, who bore a startling resemblance to Marlene Dietrich. Born Magdalene Saenger on the 26th August 1907, her father was a distinguished German publisher and ambassador to Prague. Her mother was an acclaimed violinist, hailing from Belgium and one of the first winners of the Queen Elizabeth of Belgium Prize. Lelia was a piano prodigy and a student of Arthur Schnabel. She fled Germany with her third husband in 1933, arriving in New York. Lelia toured the US with Otto Klemperer as a concert pianist before arriving in LA. Franz, Alice and Lelia all knew each other in Berlin long before moving to Hollywood and Waxman hired her to play the solo piano for a difficult number in THE ICE FOLLIES OF 1939, which she did in one take. Producer Roger Edens was so dumbfounded that anyone could play the music at all, even in one take, that he yelled “Bravo!” at the end of the recording and asked Waxman who this beautiful girl was. This resulted in her being hired as a rehearsal pianist at MGM. Leila became a major player in the Freed unit at the studio. She served as Arthur Freed’s executive assistant for almost twenty-five years, while finding the time to marry her fourth husband, film editor Albrecht Joseph, who worked on the GUNSMOKE television series.

Alice Waxman passed away on the 13th September 1957. Come 1958, divorced for the fourth time, Lella retired after working on GIGI and married Franz Waxman in Rome, Italy, on the 14th August that same year, where he was working on his score for THE NUN’S STORY. They divorced in 1965. Lelia passed away on the 23rd July 1991.

Under Contract - Waxman was more interested in composing and conducting than being an administrator and after two years, Charles Previn, second cousin to Andre, succeeded him in the role and stayed for more than a decade, before Joseph Gershenson, the most well-known of the Universal department heads, took over. Waxman was then at MGM for the standard seven year contract, from the years 1936-1942, which would result in scores for high profile films such as CAPTAINS COURAGEOUS (1937), THE PHILADELPHIA STORY (1940) and WOMAN OF THE YEAR (1942). Waxman always worked at home, as opposed to others who toiled away in their cubicles on the studio lots. Of course, any contracted person, be they composer, actor or otherwise, could be loaned out to another studio, at the contract studio’s financial benefit; so MGM loaned Waxman to independent producer David O. Selznick for THE YOUNG IN HEART (1938), which was Oscar-nominated for both Best Score and Best Original Score and again for REBECCA (1940), securing a third Academy Award nomination, for Best Score. Waxman was then contracted to Warner Bros. from 1943 to 1947, where he composed such scores as MR. SKEFFINGTON (1944) and the following year’s sparsely scored TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT, most famous for the screen debut of Lauren Bacall (whose singing was dubbed by Andy Williams). Waxman then began to freelance, which gave him more time to concentrate on projects other than film. As a freelancer, he scored such films as 20th Century Fox’s 1950 release NIGHT AND THE CITY, Paramount’s THE FURIES, and one of the big screen precursors of glossy small screen soap operas, Fox’s PEYTON PLACE (1957) and its 1961 sequel, RETURN TO PEYTON PLACE.

Waxman Winds Up Steiner - David O. Selznick, unsure that Max Steiner could complete his score in time for 1939s GONE WITH THE WIND, commissioned Waxman, who was at that time assigned to REBECCA, to write an “insurance score”. Of course, Selznick’s successfully having put the wind up him; Steiner delivered the goods with the help of a team of orchestrators and arrangers in SIX weeks. However, some music by Franz Waxman did make it into the film’s ‘Battle of Atlanta’ sequence.

Franz Waxman with Gene Kelly and the award for his 1950 score for Sunset Boulevard.

Oscar Calling - Waxman received a total of 12 Oscar nominations during his Hollywood career. He was the only composer to be awarded Academy Awards two years running – for 1950s SUNSET BOULEVARD and 1951s A PLACE IN THE SUN. For the former, Paramount will be releasing a DVD of the film for Christmas 2002 and one of the special features will be a ten-minute documentary on Waxman. For the latter, Waxman’s compositions included an alto saxophone denoting Elizabeth Taylor’s character. Waxman went to great lengths to find the right saxophonist for the job and auditioned a hundred musicians, before finally settling on Ted Nash. As a saxophonist myself, I feel it is one of the few instruments where an individual’s tone can vary so greatly from that of another, so Waxman’s time-consuming search was an astute decision. Film music aficionados will be most familiar with the RCA album conducted by Charles Gerhardt, with the sax solos on the suite of music from A PLACE IN THE SUN played to perfection by session man Ronnie Chamberlain. Another fine rendition of the suite was on the album ‘Music from Hollywood’, a live recording of a 1963 Hollywood Bowl concert featuring the original soloist Ted Nash, re-released on compact disc by Columbia Legacy in 1995.

Annoyed with Oscar - Waxman resigned from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1954, in protest over Alfred Newman’s THE ROBE not receiving a nomination, which demonstrates his respect for his fellow composers. Interestingly, Waxman scored the sequel to THE ROBE, DEMETRIUS AND THE GLADIATORS, which reworked Newman’s themes from the former film.

Waxman at Work - Some of Waxman’s working practices have become standard procedure in film music composition. He felt that “the foremost principle of good scoring for motion pictures is the color of orchestrations. The melody is only secondary.” Waxman of course wrote his own fair share of memorable tunes, as he believed “in strong themes which are easily recognizable and varied according to the film’s needs but the variations must be expressive and not complicated.” While these two comments might appear to be contradictory, in actual fact they show a keen intellect ultimately concerned with providing music which suited a given film, not taking center stage unless absolutely, dramatically necessary. Music editor and Paramount Pictures music department executive Bill Stinson remarked that, “when Franz would score a picture, he would put the dialogue in his ear and he would conduct to dialogue just to get the nuances in music that he needed.” Makes a change from a click track, I suppose! But seriously, this remark goes a long way to explain why, amongst his colleagues, Waxman’s under-dialogue music worked so well, when that of other composers could be overpowering and ultimately distracting.

As he progressed from his assignments of the early to mid Golden Age, Waxman’s predominant compositional style, influenced by the music of Wagner, Strauss, his fellow Hollywood composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and also the stylisms of Shostakovich and Prokofiev, was slowly superseded by a more forward-thinking, progressive characteristic of dissonant harmonies. Those who say that it was primarily Alex North, David Raksin and Leonard Rosenman who remodelled the 19th Century approach of the typical “Hollywood Sound” should study Franz Waxman. Also, Waxman made great use of fugal writing in his film scores, proving that movie music does not have to be watered down, so-called “serious” music. Today’s composers would do well to remember this. From the Latin “fuga”, meaning “flight”, a fugue is a technique where one voice states a theme, which is developed by further voices, before returning to the opening statement. One of the best examples of his use of a fugue is to be found in the Oscar-nominated OBJECTIVE, BURMA! During the parachute drop / hill-climbing sequence, the music adds to the struggle as each layer builds on the previous layer. Another Waxman-ism is the use of the passacaglia, wherein a theme in the bass is continually repeated while variations are introduced around it, a good example being the climactic scene in SORRY, WRONG NUMBER (1948), the music increasing the tension greatly. For more familiar examples of a passacaglia and fugue, just think of Jerry Goldsmith’s THE BLUE MAX and the final aerial battle, which took him more time to write than the rest of the score.

Another working example is Waxman’s use of the luftpause, which is a pause for a dramatic point; for instance, in the climax of the “Asleep” cue from THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS. Another may be found in the last minutes of LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON, when Audrey Hepburn is running alongside the train as it leaves the Paris station. The music is building. When Gary Cooper sweeps her up on board, the music stops for a second or two to make the moment more dramatic.

In the contemporary film and television environment, one often hears of composers working on many projects either simultaneously or back to back. But it has been proven that composers in the Golden Age worked on many more films, with or without help, than is the norm today. John Waxman, who first became aware of what his father did for a living around the time of OBJECTIVE, BURMA!, has his own recollections of the time his father was working on three high profile films at the same time: “He’d get up in the morning and work on a contemporary jazz score for CRIME IN THE STREETS until breakfast, take a break and work on a Kirk Douglas western called THE INDIAN FIGHTER until lunch, and then from lunch till dinner, work on THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS.”

More Time for Research - Franz Waxman represents a good example of how important it is for a certain amount of musical research in some film scores. Today, many ethnic sounds are layered in, often through the use of samples, with little actual research. Time is the biggest hurdle as to why this is not done nowadays, with three weeks being an average time to compose and record a score. In the Golden Age, one may have had longer in which to deliver the goods but it still speaks to the composer’s merit. Undoubtedly, Waxman was not the only composer to indulge in a great deal of research. Miklos Rozsa researched historical and geographical idioms for many scores, including QUO VADIS and BEN-HUR.

For PRINCE VALIANT (1954), Waxman composed in an English idiom, combining early madrigals with post-romantic symphonic writing. More revealing is that, commissioned to score THE NUN’S STORY (1959), Waxman wrote a letter to director Fred Zinneman and producer Henry Blanke, in which he asked for an earlier starting date, explaining his reasons in a most literate manner. In part, he said “We need time – time to create”. Unfortunately, this is one luxury composers do not often have but in Waxman’s case, he got the extra time and the results were worth it, earning Waxman his eleventh Academy Award nomination. The music was recorded in Rome, where Waxman had gone to the Papal Institute of Religious Music, to research Gregorian chants, which were to form the basis of the score. He also made the singular use in his film music of the twelve-tone scale to depict the insane asylum in the film. At the Oscars, THE NUN’S STORY lost to Rozsa’s BEN-HUR, a score which Waxman said deserved to win, stating that Rozsa was “the best film composer”. Producer Blanke praised Waxman’s efforts in the original album’s liner notes, stating “I feel that this is as close to the perfect dramatic motion picture score as has yet been written.” Not bad, considering that Zinneman had originally thought the film did not need music but Warner Bros. had dictated otherwise, as they had no faith in the film and thought music might help.

In 1962, Waxman had the good fortune to have been invited by the Soviet government to conduct in Russia, thus becoming the first American conductor to conduct the major orchestras of the USSR in Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev. While there, he found time in Kiev to study Ukrainian folk music, which he put to good use in his score for the same year’s TARAS BULBA, including the understandably celebrated sequence ‘The Ride to Dubno’, a tour-de-force musical extravaganza for a score he was fond of and which earned him his final Academy Award nomination. These three scores are amongst the most respected in film music circles.

Television - Waxman was not a snob when it came to the small screen, which used his PEYTON PLACE theme for the ensuing series. He also composed for series such as GUNSMOKE and ARREST AND TRIAL and the music for ‘The Sixteen Millimetre Shrine’ episode of Rod Serling’s acclaimed anthology series THE TWILIGHT ZONE. The story and, therefore most logically, the score, covered similar territory to that of the Waxman-scored SUNSET BOULEVARD.

In 1947, Waxman founded the Los Angeles Music Festival, and over the course of two decades used it as a platform to champion American composers and introduce significant international composers with over seventy premieres including works by Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Shostakovich. (Waxman with Stravinksy in 1960.)

Festivities in the City of Angels - In 1947, Franz Waxman founded the Los Angeles Music Festival and it was through his efforts as principal conductor and music director during the ensuing twenty years until his untimely death, that he brought many works to the West Coast. Amongst these premieres were Claude Debussy’s Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, Arthur Honegger’s Joan of Arc at the Stake, and Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem (Waxman conducted the West Coast premiere, which was its second performance in the United States), as well as symphonies by Shostakovich, Prokofiev and William Walton. Stravinsky, who never managed to compose for film himself, despite a number of his students using his techniques in their film music, was featured with Soldier’s Tale and his opera The Nightingale. The composer himself conducted the world premiere of his ballet Agon and gave the US premiere of his Canticum Sacrum at the 1957 Festival. The previous year, Waxman conducted the West Coast premiere of Miklos Rozsa’s Violin Concerto.

Concert Hall Composer - Concerts of the Los Angeles Music Festival, 1947-1966 - Franz Waxman is one of the few composers whose film music translates well to the concert hall and this reflects upon the fact that he did not differentiate between his film and concert hall music. Unlike Miklos Rozsa, he did not lead a ‘double life’; he did not draw clear lines of demarcation between his programmatic and concert compositions. Like Erich Wolfgang Korngold, for example, Waxman adapted material from his film music. His Elegy for string orchestra and harp came from OLD ACQUAINTANCE (1943), while Ein Feste Burg was taken from EDGE OF DARKNESS (1942) and Overture for Trumpet and Orchestra was based on music in THE HORN BLOWS AT MIDNIGHT (1945). The Carmen Fantasy for violin and orchestra was based on themes from Bizet’s ‘Carmen’ for the film HUMORESQUE (1947, an Oscar nominee for Best Score), which was performed on the soundtrack by the violinist Isaac Stern and Jascha Heifetz recorded it for the RCA label. A new generation of violinists have championed this work and Maxim Vengerov’s recording with Zubin Mehta and the Israel Philharmonic has become a legend in our own time. Of course, some of Waxman’s film scores were fashioned into suites for concert performance, such as A PLACE IN THE SUN, REBECCA and SUNSET BOULEVARD. Waxman was also fascinated by Stevenson’s ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’, for which he wrote the music for the 1941 film version starring Spencer Tracy; for years he worked on and off on an opera but it was never completed. One might surmise (although it is not actually the case) that this, too, contained material from the film score, which was Academy Award-nominated for Best Scoring of a Dramatic Picture, along with his SUSPICION. Waxman did sometimes feel like turning his back on Hollywood and writing purely for the concert hall but as his son observes, “he was basically a dramatist and loved the challenges that a new film score assignment presented.”

Among Waxman’s other concert hall works are 1955s Theme Variations and Fugato for jazz orchestra and Sinfonietta for Strings and Timpani, the oratorio Joshua four years later and the following year’s Goyana. Perhaps his most heartfelt non-film work, The Song of Terezin was commissioned by the May Festival of Cincinnati and performed there in May 1965. This was a song cycle for mixed chorus and orchestra, which had its origins in ‘I Never Saw Another Butterfly’, a collection of poems by children interned in the Theresianstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia during World War II. Fritz, one of Waxman’s brothers, had died in a concentration camp while another, Max, was killed in action in the First World War (also, a brother and a sister had both died in infancy).

What If…? - Franz Waxman turned down the film MARTY (ultimately scored by Roy Webb and analyzed by this writer in Soundtrack Vol. 20, No. 77), as his son comments “he did not think the public would be interested in the life of a butcher”. It went on to win the 1955 Oscar for Best Picture. Due to scheduling conflicts, he also was unable to score such films as THE EGYPTIAN (co-composed by Alfred Newman and Bernard Herrmann), THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA (Dimitri Tiomkin), SPARTACUS and CLEOPATRA (both scored by Alex North). It is interesting to imagine what Waxman would have done for these films and indeed, his son John mentions that “the late Christopher Palmer and I used to play the ‘what if’ game – what if Tiomkin had scored HOW THE WEST WAS WON etcetera.”

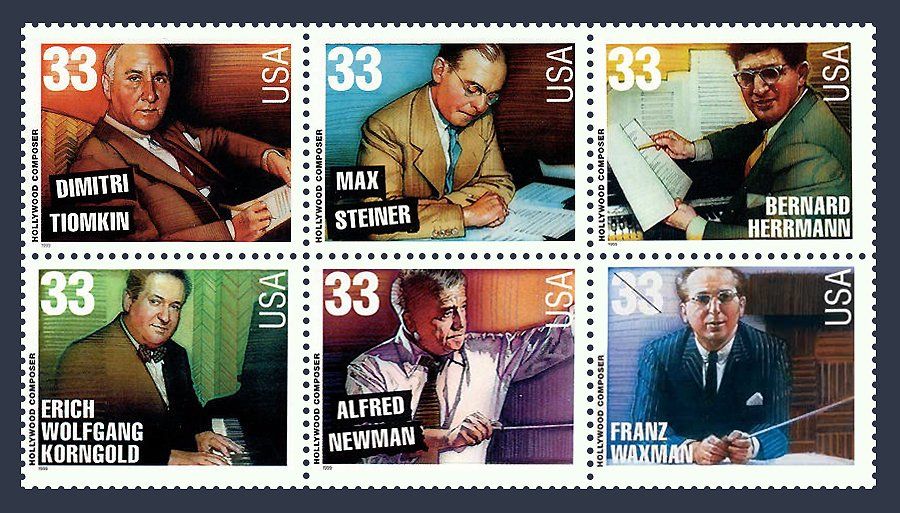

Six 33-cent Hollywood Composers commemorative stamps were issued in Los Angeles, California, on September 16, 1999. The stamps were designed by Howard Paine of Delaplane, Virginia, and illustrated by Drew Struzan of Pasadena, California.

Philatelist Composer - For Franz Waxman it was always music; John Waxman says that when he was not writing film scores, his father was guest conducting orchestras, writing concert works and planning the next season of the Los Angeles Music Festival. This left little time for hobbies but he was a stamp collector. Little did he know, that one day his image would grace a postage stamp of its own, along with his Golden Age colleagues Max Steiner, Dimitri Tiomkin, Bernard Herrmann, Alfred Newman and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, all painted by talented film poster artist, Drew Struzan.

John reports that some of his father’s own particular favourites of his own film scores were THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN, REBECCA, OBJECTIVE, BURMA!, CRIME IN THE STREETS and TARAS BULBA. As for non-film compositions, “He greatly admired his colleagues’ work, such as Shostakovich and Rozsa, to name a few, as well as Ravel’s ‘La Valse’ and Tschaikovsky’s ‘Svmphonv No.6.’”

The Legacy - While still actively working, Franz Waxman contracted cancer and passed away on the 24th of February 1967. His final film score is often mentioned as being the previous year’s LOST COMMAND. In fact, he composed the music for one other production that never made it into cinemas and instead turned up on television – THE LONGEST HUNDRED MILES. In his thirty two years in Hollywood, he had scored a total of one hundred and forty-four films (if one counts the films tracked with Waxman’s music, this brings the total to one hundred and eighty-eight) and it begs the question, as with the other film music greats, how they could maintain a high standard of writing over an extended period of time. This perhaps stems from the fact that he was not interested as much in the music he wrote for film as a separate entity (although, like all good music, much of it does stand on its own in the concert hall or on album) but as a part of the production, much like the costume design or the cinematography. As for the son, is he the keeper of his father’s musical legacy? “The music is his legacy. Not an individual.” In John’s opinion, is there a Franz Waxman equivalent working in film music today? “My father was multifaceted and there have been several ‘Hollywood’ composers who have successfully taken the same route.”

Franz Waxman’s legacy speaks of a highly talented individual, whose contributions to the worlds of cinema and music, through his roles as composer and conductor and concert impresario are remembered to this day and will be as long as they are people like John Waxman, record producer such as Robert Townson, and publications such as this one, to never let that legacy fade away.

Themes & Variations - As a companion to our Franz Waxman appreciation, let’s get the low-down on Waxman Junior and his own work, who has been kind enough to answer my questions, giving me a deeper insight into the work of his father.

John’s name appears a lot in various film music books and periodicals and this is because he is seen as one of the first ports of call, due to his knowledge and education. As a film historian, he is invited to participate in forums and lectures on the subject. His company, Themes & Variations supplies parts for concerts and new recordings of music for film. The company was founded when John was working on the RCA Classic Film Scores series of recordings with George Korngold and Charles Gerhardt. This series was undoubtedly one of the most important recording projects in film music and recording history in general. Without them, maverick filmmakers such as Brian DePalma and Martin Scorsese may not have “rediscovered” Bernard Herrmann (recording in England and working on European, films) and he would have not made the triumphant return to Hollywood that he did, prior to his untimely death. John Waxman says that his memories of the RCA series “are fond ones. The impact of the thirteen recordings was tremendous.”

Perhaps the direct successor to RCA and the Elmer Bernstein Filmusic Collection is the Marco Polo label. Citing a couple of works by his father, John says “In addition to Marco Polo, there is Bob Townson’s fabulous series on Varese Sarabande. PEYTON PLACE is a great recording and from what I have heard so far, REBECCA is also going to be wonderful.” But surely, there is already a representative album of the latter score on Marco Polo, why re-record it yet again, when so much of Franz Waxman’s work remains unpreserved on disc? “When Marco Polo recorded REBECCA, it was not under the best conditions [the early recordings were made in a church, which resulted in a poorer-than-hoped-for sound]. But that has changed recently thanks to John Morgan and Bill Stromberg. OBJECTIVE, BURMA! and MR. SKEFFINGTON are both excellent CDs. In addition to these, there will be at least two or three original soundtrack recordings coming from Varese Sarabande and Film Score Monthly in 2002-2003.

The music parts housed in the rental library were reconstructed from the composer’s original sketches and orchestrations, although of course a number of concert arrangements do differ from the film versions, be they those of Jerry Goldsmith or John Williams, to name just two fan favorites. But if you would like to get your hands on a copy of the music, think again. Themes & Variations does not send, sell or lend scores to fans or collectors, only to professionals.

John is also a consultant to recording labels such as Decca, Koch, Nonesuch, Philips Classics, Silva Screen, Sony, Telarc and Varese Sarabande, helping in preparing recording projects. Themes & Variations also represents Famous Music Publishing Companies, the music subsidiary of Paramount Pictures. From the Columbia Pictures library, the company has James Horner’s THE MASK OF ZORRO, Patrick Doyle’s SENSE AND SENSIBILITY and Thomas Newman’s LITTLE WOMEN. T&V, to use its website address acronym, has restored many of the major works by Bernard Herrmann, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Alfred Newman and Max Steiner (among others), while every year adding such contemporary works as Stephen Warbeck’s SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE and Rachel Portman’s THE CIDER HOUSE RULES and CHOCOLAT. Two years ago, John added a recording unit to the T&V family.

‘Celebrating the Classics’ was the premiere release – this was to commemorate the release by the US Postal Service of the ‘Hollywood Composer’ series of six stamps. John also mentions that “my next record project will be called ‘Alone in a Big City…’, aka the Franz Waxman Songbook. This CD will feature songs composed by Waxman Senior for German and French films before he came to the United States. The songs will be sung in German, French and English.”

John played the piano and violin as a youngster – but, even though his father was “in the business”, there was no pressure on John – Franz and Alice’s only child – to play an instrument. Although he never contemplated following in his father’s footsteps, he has created suites from film music for his rental company. I was curious as to whether the Waxman line might result in another composer for film with the illustrious surname – are there any other relatives who work in the arts, or entertainment field? “No, not directly in music but our daughter Alyce is a graphic designer and our son Joshua is a lawyer.”

As regards his father’s works, John's “personal favourites are not, restricted to his film music, I appreciate his classical works as well, such as his soon to be recorded oratorio ‘Joshua’ and ‘The Song of Terezin’, which was released by Decca for their Entarete Musik series.”

Has John ever contemplated writing a book about his father or indeed is he aware of any such plans? “I’m thinking about it. There are several books in the works.” But has he found that everything written about the subject today has nothing new to say? That everything there is to be said has been covered or is there anything he personally would like, to see covered? John’s answer is enigmatic: “That’s for my book.”

Primary Sources

The Composer in Hollywood by Christopher Palmer, Marion Boyars, London 1993

Music for the Movies (Second Edition) by Tony Thomas, Silman-James Press, CA 1997

Film Score: The View from the Podium by Tony Thomas, A.S. Barnes and Co., NJ 1979

Listening to Movies: The Film Lover’s Guide to Film Music by Fred Karlin, Schirmer Books, NY 1994