Webb was at home in a variety of film genres – scoring World War II pictures like BOMBARDIER, PARACHUTE BATTALION and THE FIGHTING SEABEES, domestic dramas like BILL OF DIVORCEMENT and FATHER TAKES A WIFE, westerns like PAINTED DESERT, BADLANDS and TALL IN THE SADDLE, fantasy and horror films like THE BODY SNATCHER and MIGHTY JOE YOUNG, historical dramas like THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS and ABE LINCOLN IN ILLINOIS, suspense thrillers like NOTORIOUS and STRANGER ON THE THIRD FLOOR, comedies like MY FAVORITE WIFE and BRINGING UP BABY, plus uncategorical low-budgeters like ZOMBIES ON BROADWAY and the MEXICAN SPITFIRE movies. Webb received Oscar nominations for his scores for QUALITY STREET (1937), MY FAVORITE WIFE (1940), JOAN OF PARIS (1941), THE FIGHTING SEABEES (1944) and ENCHANTED COTTAGE (1945).

Cat People

The Vintage Score / Music by Roy Webb / Analysis by Randall D. Larson

Originally published in Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine No.36, (199)

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor and publisher, Randall D. Larson

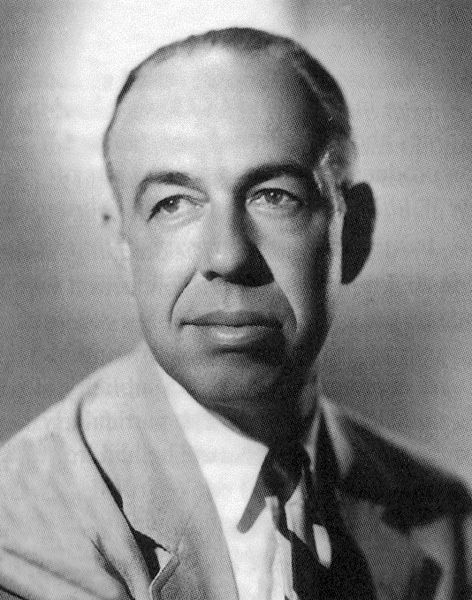

One of the most versatile composers of the 1930’s and 1940’s was Roy Webb, whose twenty-five year tenure with RKO Pictures resulted in a plethora of effective and memorable film scores in a wide variety of musical styles and film genres.

Born in New York City on Oct. 3, 1888, Roy Webb had initially been interested in art, attending New York’s Art Student’s League, where he studied drawing and painting. His interest in music only came to light when he volunteered to write background music for plays put on by the League. Discovering his knack for music, Webb enrolled at Columbia University, where he wrote music for variety shows and composed the University’s fight song. A songwriting career ensued; Webb also became one of the co-founders of ASCAP in 1914.

During the First World War, Roy Webb enlisted in the Navy and was attending Officer’s School when the Armistice was signed. After being honorably discharged, he became an assistant director and later an art director for the Famous Players; eventually returning to the world of music when he accepted a conducting job on Broadway for the Fred Stone show, Stepping Stones. This production toured for two and a half years, Webb recruiting some of his musicians locally from the towns and cities in which the show played – they had to be ready for the opening with little more than an hour-and-a-half’s rehearsal!

When sound came to motion pictures in 1929, Webb embarked for Hollywood. He orchestrated the music for RKO Radio’s Rio Rita before returning to New York for more work on Broadway. He returned to RKO in 1935 as an assistant to Max Steiner, then head of the music department (and a pioneer of motion picture music himself, having scored RKO’s monumental KING KONG in 1933, one of cinema’s first full-blown symphonic scores). Webb’s first assignment was as musical director for THE LAST DAYS OF POMPEII, and he went on to supervise and design music sequences for films such as GUNGA DIN (scored by Alfred Newman), and CITIZEN KANE (scored by Bernard Herrmann). Webb also composed more than 200 film scores himself, beginning with 1935’s ALICE ADAMS.

Roy Webb retired from motion pictures in 1958; he died of a heart attack at the age of 94 on Dec 10, 1982, leaving behind a legacy of effective and memorable film music. Much of Webb’s music is certainly among the best of The Golden Age of Hollywood Movie Music.

Among his most interesting work are those scores for fantasy and horror pictures, all of which were approached with his characteristic delicacy and subtlety. Within the fantasy genre, Webb’s earliest efforts included such marginally fantastic pictures as THE NITWITS (1935) and MUMMY’S BOYS (1936), and the cartoonlike I MARRIED A WITCH (1942), but his most notable work in the genre began in 1942 with Val Lewton’s CAT PEOPLE. Webb went on to score nearly all of Lewton’s macabre RKO pictures — THE LEOPARD MAN, I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE, THE 7TH VICTIM, GHOST SHIP, CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE, THE BODY SNATCHERS and BEDLAM (Webb didn’t score ISLE OF THE DEAD, which was composed by Leigh Harline). Just as Lewton and his directors Jacques Tournier, Mark Robson, and Robert Wise provided a mysterious visual ambience for these films, Webb’s evocative music likewise contributed an important sonic ambience. Often drastically shifting musical gears to match the milieu or style of each picture, Webb’s style in these films is subdued, subtly underlining Lewton’s sense of quiet suspense and haunting dream likeness.

CAT PEOPLE marked Webb’s first collaboration with producer Val Lewton. Webb, along with RKO music director Constantin Bakaleinikoff, were brought into the picture before even the screenplay was written, an unusual practice as most composers, in those days as now, were normally consulted only during post-production. Lewton, however, did not want to settle for the pastiche scores often assembled for low-budget pictures, and involved Webb even in the story sessions, where he contributed ideas for linking visuals with music. Webb later said that by being involved in the planning, he was able to provide a more effective score.

Webb’s intricate and commentative score is interwoven with no less than seven distinct themes, each of which centers around Irena, the mysterious Serbian immigrant who suffers under the curse of the Cat People, transforming into a vicious panther during moments of high passion. Irena is central to the story, and Webb’s music constantly reassociates itself with her personality and her heritage.

The music for CAT PEOPLE is notable for its restraint. Webb avoids bombastic symphonics and ambient dissonance, preferring simple orchestrations and quiet themes which develop intricately to underline and support the subtle atmospheres of dread and spookiness created by the filmmakers. The music is often sparse, containing brief moments of music built around a variety of leitmotifs which interact together to comment subtly on characters and their interrelations. Especially notable is the contrast between extended periods of silence and sudden surges of music, contributing much to the stark, haunting atmosphere of these films. A large percentage of the score’s 25 minutes of music underscores dialog, commenting on characters and their relations more than activities or occurrences. In fact the suspense scenes in the film’s second half are nearly all without music, achieving their own atmospheric undercurrent through silence and soft sound effect.

The CAT PEOPLE score opens with mysterious chords, heralding fantasy and mystery, under the opening credits. This segues into the Main Theme, five sing-song notes, two descending followed by three descending. The music ends as do the titles, and the introductory sequence in the zoo where Oliver meets the exotic Serbian, Irena, has no music. Only when they are drawn together as their romance begins (and with it the various entanglements caused by Irena’s mysterious affliction) does Webb introduce and develop all his other themes, varying them according to the developments in Irena’s lycanthropy.

There are a total of seven distinct themes, which are woven together and interrelated in complex fashion

1. Main Theme (Serbian Lullaby): For his dreamlike film, Val Lewton had wanted a lullaby theme that was suited to a story about cats, yet had a haunting quality to it. He discovered a traditional French lullaby called “Do, Do, Baby Do,” and Webb agreed that it would make an ideal leitmotif for the picture. This motif denotes Irena’s heritage and her curse, constantly intruding upon the other themes as an ostinato of danger, the shadow behind Irena’s outward innocence.

The melody recurs frequently, both as a brief ostinato, reminding the viewer of Irena’s deadly heritage (as when the pet kitten she is given by Oliver hisses at her, and when she reaches for the caged bird which panics and dies) as well as in developed variations for strings and woodwind (it is this theme which is used, not the Love Theme, when Irena and Oliver confess their love for one another, a subtle suggestion that the Love Theme, like the romance between the two, remains subservient to the dominating influence of Irena’s heritage and its corresponding music.)

The Main Theme will recur often, frequently playing with or against the other themes to emphasize aspects of Irena’s character or the deepening mystery. Its five notes are tapped out in an ostinato as Irena struggles with her feline compulsion, as when she carries the dead bird to the zoo, or when Oliver suggests that she consider psychiatric treatment for what he suspects is simply a delusion. The theme sounds dreamily as Irena does visit Dr. Judd in an attempt to overcome her compulsion through psychiatric means; this dreamlike quality is later matched by similar use of the motif in Irena’s nightmare.

2. Love Theme: a subtle melody for soft strings-and-woodwind, associated with Irena’s developing romance with Oliver. First heard when Irena invites her new friend up to her apartment for tea, a furtive clarinet figure sounds as Irena says “I’ve never had anyone here… you’re the first friend I’ve had in America.” When they go inside the romantic melody is heard softly from romantic violins. The theme underscores their growing romance, softly pleasant and joyful, until it turns tragic as the reality of their marriage begins to crumble under the weight of Irena’s Serbian curse.

It will alternately sound happy or sorrowful depending on Irena’s mood; like all the other themes, the music is constantly subservient to the influence of Irena’s feline lycanthropy. On their wedding night, there is a brief cue for violin and harp when Irena sadly insists on sleeping in separate rooms – the theme broken momentarily by a far-off panther cry from the zoo – signifying the reason for Irena’s reticence. The Love Theme plays happily when Irena returns from her visits to the psychiatrist, hopeful about being helped; and each time it turns sour, first when she learns that Oliver’s co-worker Alice recommended the doctor, and therefore knows about her assumed mental illness, and the second time when Oliver says he wants a divorce.

3. Hopelessness Theme: Consisting of nonmelodic high violin figures (which derive from the Main Theme) counterpointed by descending strokes of low viola, this is the thematic counterpoint to the Love Theme. I call it the “Hopelessness Theme” because it is associated with Irena’s apprehension towards her marriage with Oliver, the dissolution of their closeness and eventually their marriage; it underscores Irena’s hopelessness towards her marriage and, ultimately, life itself. Like Irena’s romance, the musical theme is unresolved, static and stationery.

The Hopelessness Theme is first heard, from mysterious strings and woodwind, as Oliver and Irena confess their love for each other. The music reflects Irena’s obvious apprehension toward a physical relation with Oliver; she knows the transforming effect passion will have upon her, and even in the blossoming of their love. Webb’s music, rising higher for violin figures counterpointed against lower, descending viola strokes, adds to the image of Irena’s worried, shadowed face, portraying the impossibility of their romance. The Hopelessness Theme reinforces this idea throughout the score, emphasizing both Irena’s pessimism toward romance and Oliver’s increasing interest in co-worker Alice. It’s used when Oliver and Irena argue about Alice; when Irena wakes during the night and wanders to the zoo; when jealous Irena heads for Oliver’s workplace to confront he and Alice; and finally when Irena leaves home for the last time after the death of Dr. Judd.

4. The Cat People Theme: This brief ostinato is something of a herald of danger, four quick notes sounding a sudden warning, suggesting Irena’s evil side. It is first heard when Oliver gives Irena a kitten as a present, but the animal reacts with fear and hisses at her. The theme punctuates the moment and suggests that there is something unusual about Irena; it is followed by the Main Theme, which further reinforces Irena’s strange heritage. Similarly, when Irena, having exchanged the kitten for a bird, reaches into its cage one day to stroke it, the bird panics and dies, the music reflecting why: the Cat People herald punctuates the shocking incident, associating it with Irena’s evil side, while the Lullaby theme which follows again relates to the Serbian heritage which is the basis of Irena’s curse.

5. Irena’s Theme: a descending/ascending/descending motif for soft violins, melancholy and barely discernable beneath the dialog; this motif is associated with Irena’s regret at her lycanthropic condition and, finally, her death. Like the Love Theme(s), the melody is sad and delicately soft, reflecting the tragedy of Irena, while the menacing ostinatos reflect her evil. Irena’s Theme first segues out of the Cat People and Lullaby Themes when the kitten hisses at Irena and she suggests exchanging it for a bird. Later, when the bird dies in fright and Irena puts it in a burial box, the music connects the two scenes and reflects Irena’s regret and sadness. It is used again briefly when Irena returns from a late night visit to the zoo, and finally, when Alice and Oliver arrive at the zoo to find Irena dead, the victim of the panther she set loose.

6. The King John Theme: a regal, hymn-like melody associated with the legend of King John of Serbia told by Irena to Oliver. During his first visit to Irena’s apartment, Oliver asks about a statuette of a horsebacked knight spearing a panther. Irena says it’s Serbia’s King John and the panther represents the evil forces he vanquished from their country. Webb here introduces the King John Theme, its majestic chords lending a backdrop of important legendry to her retelling. The legend symbolizes much of Irena’s internal conflicts, and the music’s religious quality reinforces its affect on Irena. Later, when Oliver and Irena discuss the dead bird (they are seen in profile, with the King John statuette in foreground), the theme recurs when Irena mentions the Serbian legends and Oliver reassures her. The motif is reprised again in the End Titles.

7. Irena’s Perfume Theme: a brief theme associated with Irena. This a jingly motif for bell-tree is introduced when Oliver first enters Irena’s apartment. As he sniffs the air and remarks on the exotic scent which wisps through the air, the motif is briefly heard. Later, when Oliver and Alice leave the office building after their close encounter with the panther, Alice smells Irena’s perfume in the air. The same bell-tree motif underscores her remark and associates their confrontation with Irena.

All these themes interact frequently, both to punctuate and support visual action and (more importantly) to musically portray the multifaceted character of Irena. Webb’s use of leitmotif to symbolize or emphasize elements like these is particularly remarkable in this score. During the scenes where animals react to Irena in panic or fright (the kitten, the bird), the Cat People Theme sounds with surprise and significance, followed by the Main Theme which reinforces Irena’s strange heritage, followed by Irena’s Theme which humanizes the situation. The first two themes represent Irena from outside points of view while Irena’s Theme portrays her own tortured emotions.

An excellent moment occurs during Irena’s nightmare, starting out quiet, low and furtive woodwind notes, gradually ascending, then segueing into spiraling violin notes as the dream is visualized. Interestingly, though the dream depicts King John, Webb does not use the King John theme – remaining increasingly dissonant to emphasize the disturbing symbolism of Irena’s nightmare. The Main Theme is heard from frenzied, vibrato strings as the dream reaches its climax.

The spooky scene in which Alice is stalked by the panther at the indoor pool has no music, achieving its eerie mood purely through the shadowy photography and echoed sound effects. Later, when Oliver and Alice are trapped in their office by the prowling panther, Webb serves up low, quivering violin chords, spiraling up and down, over and over, eventually joined by woodwind and horns as the panther stalks them through the forest of drafting tables. When Oliver holds up the crucifix-like T-square and cries “In the name of God, Irena, leave us in peace!” the music dissolves, seemingly exorcized along with the ghostly panther.

Webb supplies superb action music for the climactic scene where Irena attacks Dr. Judd, his seducing kiss awakening the panther in her. The Main Theme sounds softly and staccato as they kiss, the music then growing into a wild orchestration of trumpets, whirling strings and pounding snare drum as she is transformed into a panther and attacks Judd. Whirling strings propel Oliver and Alice up the stairs when they arrive and hear the screams, broken by a phrase of the Main Theme as we see Irena hiding in the shadows, punctuating her presence. The music turns soft and sad as they discover the psychiatrist dead, then the Main Theme (vibrato strings and high, shivering tones) accompanies Irena’s return to the zoo, segueing into the Hopelessness Theme as she goes to the panther cage and unlocks it with her stolen key. The Hopelessness Theme sounds richly from violin as Irena, mortally wounded by Judd’s cane-sword, she stands resolutely in front of the cage door – finally the panther leaps out and attacks her before darting away to be run over by a taxi. When Oliver and Alice arrive to find Irena dead, Irena’s Theme sounds sadly a final time, as Oliver realizes Irena hadn’t imagined her feline affliction after all. The motif rises triumphantly (at least now, Irena is at peace, after enjoying momentary happiness with Oliver) and surges into a resolute conclusion.

Roy Webb reprised nearly all of the original CAT PEOPLE themes and merged them with new material when he scored Lewton’s light-fantasy sequel, CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (1944). Here, the heraldic Cat People Theme, the Love Theme, and the Main Theme resound both to recall the original story and also to lend a new sense of legendry and mood to Lewton’s fairy tale story of a child’s imaginary playmate.

As noted earlier, Webb composed music for a wide variety of films and in a wide variety of styles. For his prolific and varied output, Roy Webb is one of the most unsung heroes of 1940’s film music. CAT PEOPLE is only one of several scores in only one of many genres, yet it’s a prime example of Webb’s soft approach to these kinds of films, and of the leitmotif style at which he excelled.