An Interview with Fred Katz

A talk with Fred Katz by Randall D. Larson

Originally published in CinemaScore #11/12, 1983

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor and publisher, Randall D. Larson

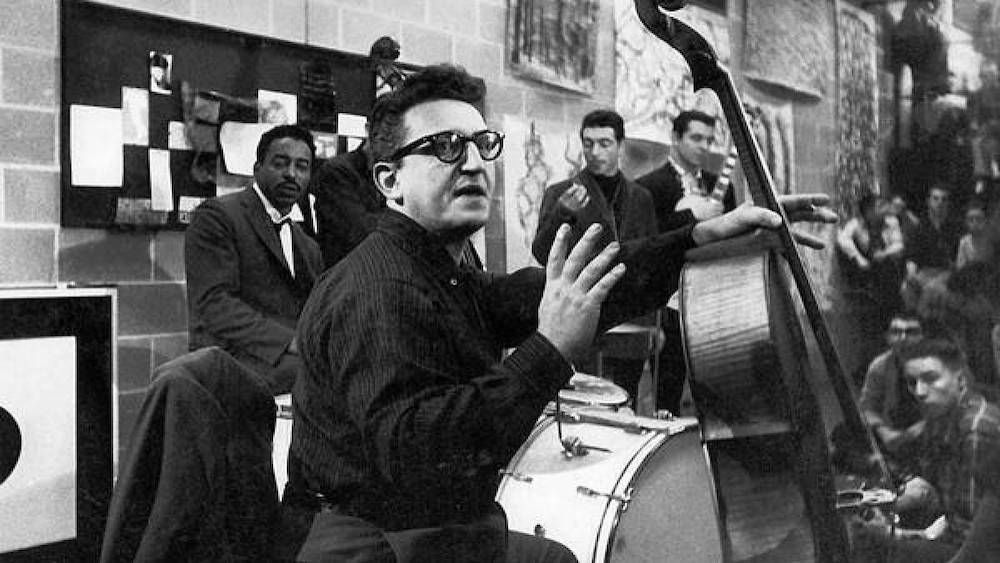

Late night, low-budget horror movie aficionados have no doubt run across Fred Katz’s name in connection with the up-beat, jazzy scores he provided for a handful of Roger Corman produced horror films, including THE WASP WOMAN and the popular LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS. Katz’s brief musical career in films and television began in 1957 and lasted through the early 60s, when he devoted full time to concert composition, mostly in the jazz field.

Born in Brooklyn in 1919, Katz won scholarships at an early age in cello and piano, soon playing with Lean Barzin and the National Orchestra at Carnegie Hall and later with Hans Kindler and the National Symphony of Washington. As a self-taught arranger and composer, Katz wrote for the ‘Treasury Bond Wagon Shows’ and conducted the Federal Employees Chorus. He was invited twice as a guest of President and Mrs. Roosevelt to conduct a choral performance in a national radio broadcast from the White House. During the Second World War, Katz, while serving in the combat Medical Corps., acted as Musical Director of the 7th Army Headquarters, arranging and composing for Army shows and radio broadcasts. While in Germany, Katz also conducted the Heidelberg Symphony in Handel’s Messiah, with full soldier chorus.

After the War, Katz worked as pianist, conductor, arranger and musical director for many popular recording artists including Vic Damone, Lena Horne, Betty Button, Frankie Laine, Tony Bennett, Carmen McRae, Harpo Marx, Tab Hunter and Paul Horn. He eventually became associated with jazz artist Chico Hamilton and was a founding member of the Chico Hamilton Quintet. Katz contributed to the writing and arranging of the group’s material, which led to his work being recorded on a number of jazz-oriented record albums, as well as resulting in his short career as a film composer.

Katz also worked for Decca Records, producing their Mood Series; he composed music for a variety of television commercials (Toni’s Adorn, Hunts’ Pork and Beans, Englander Mattresses, beer commercials, etc.); and composed classical works utilizing jazz roots and Katz’s own Chassidig heritage, including ‘Song of Songs’ (performed at Temple Ahavat Sholem), ‘Jazz Hebraica’ (performed at the Valley Jewish Community Center and Temple, and broadcast twice on CBS-TV), and scores for ‘The Little Prince’ and ‘God’s Troubadour’ (performed for the Valyermo Festivals at St. Andrew’s Priory). His Cello Concerto was performed at the Oberlin Music Conservatory for their Centennial celebration. Other concert pieces have been performed at the Bath Music Festival and the Los Angeles Music Festival.

For the most part, Katz has put his film music endeavors far behind him, but he nevertheless made some memorable contributions to movie music, particularly in the use of jazz in film music, and deserves a place in the film music heritage of cinema’s recent past.

Interviewed on February 22, 1983, Fred Katz recalled his days as a film music composer.

How did you first become involved in the film music field?

I didn’t really write that much music for films, just a few. I got started when I was in the Chico Hamilton group, and one night the director Sandy Mackendrick came in to hear us play. I had written some things that he liked, and he wanted the group in his picture, THE SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS. When we stopped he talk about it, he asked me to do the writing for the picture. That was my beginning.

Now, there’s a story about this that Sandy talks about, and that is that the original score that I wrote is the one that Sandy liked very much, but the people at the studios felt that it was too esoteric, so they hired Elmer Bernstein to do the score for the film. But I did all the jazz writing for the picture. Sandy never forgave them for that because he felt that what I had done was really far closer to what he wanted.

Then I got called by Roger Corman, and I did a picture for him, BUCKET OF BLOOD. There was another thing, a ski film (SKI TROOP ATTACK) about ski soldiers during the Second World War. LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS was taken out of soundtracks I had written for Corman and pieced together by a music editor, so even though my name is on the credits I didn’t actually write music for that particular film – but it is my music. I did a couple of shorts; there was one called T IS FOR TUMBLEWEED, a very beautiful picture and I think it won the Academy nomination for shorts. I did a thing called THE LIFE OF GAUGHAN I did some music for an animated film called THE PUPPET SCREAMS that won many awards. I did the music for APHRODITE, a very beautiful film, told as a myth.

There was a medical association that asked me to write music for some of their films, and one of them was called NEVER ALONE. I did a picture called HORIZONTAL LIEUTENANT, and I did all the Japanese music in that film. Then I did some TV things, like CHECKMATE, HOLLYWOOD IS MY TOWN; there was a pilot called GRINDL that never really got off the ground, and I did a television movie, THE THIRD COMMANDMENT, where I used avant-garde jazz. That just about covers it, I think.

Your background is basically in the jazz field, then.

Actually, my background before jazz was completely classical. I went into jazz later.

Did your jazz background at all affect your approach to film scoring?

Not really; only as a musician. Sometimes, for example in the picture T IS FOR TUMBLEWEED, a lot of the music I wrote had no jazz at all. If they wanted a jazz score, then of course my background helped. Generally speaking, though, I’ve written ‘Renaissance’ music, I’ve written jazz things, I’ve written very classical things, and I’ve written very avant-garde things. The jazz background only helps if you’re asked to write a jazz score.

So your approach to film scoring wasn’t dependent on your jazz inclinations?

No. We all had the same approach; we talked with the director, and he’s the one who really decides what’s going to happen with the music. He may want to have dramatic music for a dramatic shot, but sometimes he may want to play against it. I also worked with the music editor, whose opinions I really respected, and he would say “well, this could do with music, this should maybe be without.” But, generally speaking, the director makes those decisions. For example, Sandy Mackendrick would sometimes say to me that silence can build up suspense more than music can, so when I did the music for his film it was not as heavy as it might normally be; that’s why he objected to the way the music finally came in, because he didn’t really want that much.

How would you describe the conditions working for Roger Corman in the late 50s and early 60s?

Very pleasant, actually. There were no problems, I hardly saw him, really. He pretty much completely left me alone; I worked with the music editor there.

What was the musical philosophy for some of those low-budget films that you scored for Corman?

I don’t know really how to answer that. As far as I was concerned, I got paid and I wrote the best I could. You might even be interested to know that in some of the so-called low-budget films, some of the most experimental and avant-garde music came out of them because they figured, “what the hell, you’ve got nothing to lose, let’s try something different.” You weren’t getting paid that much, of course; actually I did it for the experience. I did a film called WASP WOMAN, and I said: “let me experiment with this, let me try coming out with different musical ideas,” and I did. The music is damn good; if you take the music away from the film, the music could stand as a series of concert pieces. So there was no philosophy. The philosophy is only to write to the best of your level.

How would you describe the music you wrote for THE WASP WOMAN?

There was sort of a hook every time she became a wasp. I wrote something that would be a hook; it was sort of a suspended series of chords, but not melodic. She’d have a headache, and I’d write headache music! We have all kinds funny things, so we’d say “oh, how do you write headache music?!” and you come up with some ideas and it works. But you write suspense, you write angry, you write violent. What I like to do, because I’m that kind of a person, is to write something whimsical. I believe that sometimes a whimsical piece of music when there’s suspense on the screen could be a very interesting kind of juxtaposition of emotions.

I notice you avoided using any “buzzing was” sounds in the score.

No, I thought that would be too obvious.

How about A BUCKET OF BLOOD? Do you recall what you were doing in that score?

Pretty jazzy. I know there was a lot of good jazz in that thing. I’m pretty sure that’s the one where it features Paul Horn, playing saxophone. It was a sort of suspense score but using jazz themes, motifs. That sort of idea.

What other types of films were you given to score?

There was a war movie about two soldiers marooned on an island – it was a very, very small budget film. I think I wrote it for three people, featuring cello and a lot of piano. I can’t remember the name of it. The other music was very poignant. You use whatever talent you have. The marvelous thing about film composers, if you are good, is that you really can write anything you want. If you tell them you want 12th Century music with a reggae beat, they’ll come up with it! They have incredible skill, and are, in that way, absolutely amazing. They can come up with anything.

While you were scoring these occasional films, what were your other musical endeavors?

I did a lot of albums, ten or twelve or thirteen, with the Chico Hamilton group, Carmen McRae, Sidney Poitier – that sort of thing. I did everything; composer, arranger, conductor.

Which area did you prefer, if any, of these various activities?

What I prefer is to write music for the concert stage. I think music for the film is fine but it’s limited; music for an album can be very exciting but it’s also limited to time. But music for the concert stage, as far as I’m concerned, is really the test. That is another thing entirely.

What did you think of scoring those horror movies?

I didn’t think anything at all. I was hoping it would lead to better gigs, but I did it, as I said, first because of the experience. I had to break in somehow, and I didn’t particularly like them. Everybody seems to like LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS, but I hated it. I hated every picture that Corman did, but you’ve got to be a professional about this. This is what you have to work on, and you do it to the best of your ability. It was the job to do and that was it. I wrote to the top of what I could write. You never write down. I don’t care what job you get, you always write to the top. That’s what integrity’s all about.

Did you work at all with any of the other Corman composers such as Les Baxter?

No, I never knew them.

Some filmographies credit you with scores by “Fred Kaz”, such as THE MONITORS and LITTLE MURDERS. Is this your work?

That’s not me. We used to get confused, but he’s from Chicago. Those aren’t my scores.

What are your current musical activities?

I was a Professor of anthropology for about twenty years, and I’ve just retired. Right now, I just finished a piece for my son, Hyman Katz – a seven-movement flute, percussion and piano piece which is, I think, a major work for me. I’m writing pieces for woodwind quintets, duets, trios, and I’m working on a concerto now for Buddy Collette. I also perform in concert; I’m constantly running jazz things, and I perform with a man who is a priest but whose background is as a jazz saxophone player. Pretty much of my work now is writing for the stage. I use a lot of Biblical subjects, mystical ideas, that sort of thing. Matter of fact, the piece for my son is based upon the prophet Zechariah and his eight visions. Now the piece for Buddy, the concerto, is a straight concerto utilizing jazz ideas, motifs, that sort of thing. That’s what I’m all about now.

Do you ever have a desire to return to films?

No, not really. If it’s a very good gig, and they pretty much leave me alone, yeah, I’ll do it, but outside of that, no. I have no desire really to get back unless it’s something very special.

I’d imagine, being accustomed to concert composing and such abstract music, you’d find the need to limit yourself to specific visuals somewhat restricting?

Yeah, that’s what I mean. Listen, I’ve heard some magnificent film scores – some of the stuff Alex North wrote, and Leonard Rosenman wrote – a lot of that music can stand by itself. But I really have no desire to get back into it.

Have you ever arranged any of your film music for the concert stage?

Not really, although some people have suggested that I do that, interestingly enough. There was one thing I wrote, for Pyramid Films, a very lovely little 8 or 10 minute film called THE LEAF, it won a lot of awards. I’ve arranged some themes from that film to be played. But, generally speaking, my personality is that I write something for that medium, and then I forget about it and go on to something else.