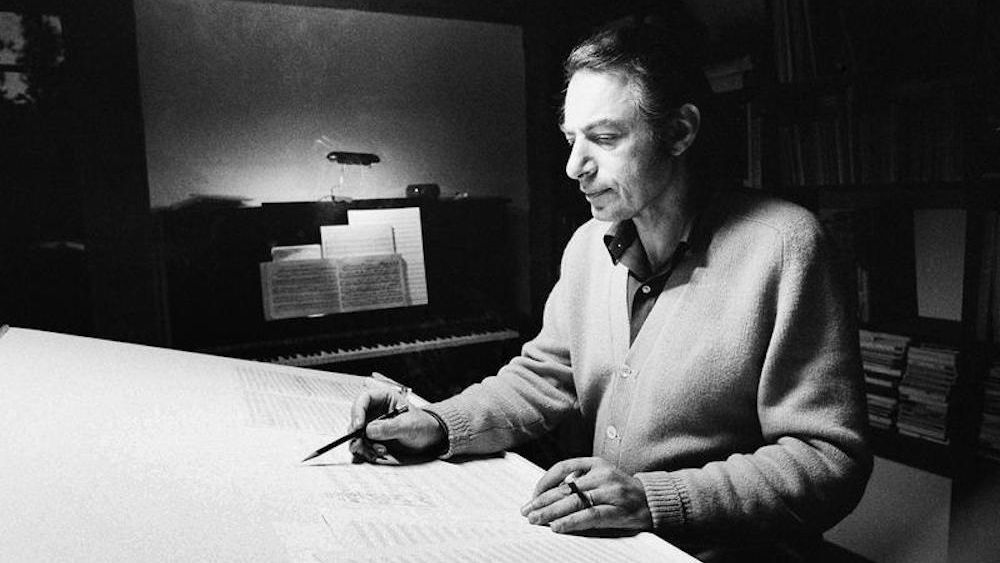

An Interview with Leonard Rosenman

An Interview with Leonard Rosenman by Wolfgang Breyer

First published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.14 / No.55 / 1995

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

Maybe it would be best if you briefly discussed your early life as a musician…

My early life as a musician did not exist: I was a painter originally, and I started piano lessons at the age of 15 just as a hobby. And then I began to win prizes for my piano playing at the age of sixteen. I went into the army, where I started to become interested in composition. When I came back, I went to the University of California; I studied with Roger Sessions and with Arnold Schoenberg in Los Angeles. Later on I won a scholarship; I went to Italy and studied with Dallapiccola. Then I became a composer and while trying to get a job as a professor in some large institute, a university or something like that, I was teaching piano on the side. One of my piano students was James Dean! He became a roommate, he moved in with us, and we became very dear friends.

I had a big concert in New York. James Dean took Elia Kazan to the concert. Kazan asked me if I’d be interested in writing the music for Jimmy’s first film, which was EAST OF EDEN. I refused, because I wasn’t interested in films. The more I refused, the more they wanted me. Finally everyone talked me into it – Steinbeck, Kazan, James Dean, Aaron Copland, Lenny Bernstein. That’s how I got into films.

The EAST OF EDEN score is considered by many (along with Bernard Herrmann and Alex North), to be the score that really brought music in films into the twentieth century. My great admirer was Benny Herrmann at the time. I had written a great deal, I had conducted, I was a pianist, and so on. I was a twelve-tone composer at the time, and I wanted to really write that kind of score. The director agreed with me, but he said, “Can you also write a beautiful tune?” And I said, “We’ll, I’ll try. You have a stop watch?” “No, but I have a second hand on my watch.” I said, “Start it.” I wrote the tune in 7 minutes. And that became the theme of EAST OF EDEN!

With COBWEB you became a kind of innovator in Hollywood film music circles. Weren’t you taking a great risk, as a young film composer?

If I wanted to be a film composer, it would have been an outstanding kind of threat. But since I didn’t take film seriously for many, many years, I thought they’d buy me the kind of money to give me the leisure to write my own work. I was totally trained for the concert field and just by luck I had gotten into films. I didn’t care. André Previn said to me at the time, “They are going to throw out your score,” I said, “I bet they won’t, there’s no frame of reference between this and any other score, it’s all atonal.” I didn’t care; I lived in New York at the time. Not that I didn’t try to do the best I can, my name was on it, but at the same time I just didn’t take films very seriously. In the concert field, everything is related to form. In the film field, the form is that of the film. At any rate, they just loved the score, because there was no frame of reference. That became one of the basic scores that influenced an enormous amount of composers in film.

Then you did REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE, the second film with James Dean. There is a very exciting main title.

I did some research in pop music at the time, I knew nothing about pop music, I had the same kind of concept that I had in EAST OF EDEN except that it was a little less complex. I had motifs for people that little by little came in counterpoint with each other.

One cue is called ‘The Planetarium’, and it is very similar to Bernard Herrmann’s score for PSYCHO. Were you aware of this at the time?

No, I didn’t know it then. I didn’t know Benny Herrmann’s music because I didn’t go to movies and I didn’t listen to film music at the time. A lot of people felt the score sounded like WEST SIDE STORY by Leonard Bernstein. I found that rather interesting, because WEST SIDE STORY came three years later! I remember I used to go to Lenny’s house with Aaron Copland and Aaron would say, “Well, he’s listening to REBEL again.” I’m not saying for a second that Lenny stole anything from me, but he was very inspired by it, like a great many people in Hollywood, probably Benny too. Benny at one time asked me to coach him in areas that he was writing in, in terms of his concert works. I liked Benny, we were good friends. At any rate, REBEL and I’d say COBWEB were the 3 very important scores in terms of how they influenced the other writers. I can’t say that I copied it from Benny, because PSYCHO came later, and Benny knew my work very well, but again he didn’t steal anything, I think he was probably very inspired by the style, and the style fit that film wonderfully.

I read that when you arrived in Hollywood, you were a newcomer, you went to a little guy at a desk in the music building at Warner Brothers and you asked him if he knew what a click track is…

It was Max Steiner. We were both waiting to see Ray Heindorf, who at that time was the head of music at Warner Brothers; he became one of my closest friends in the world. A wonderful man. And Max Steiner said, “A click-track? Yes, I can tell you about it, I invented it!” And we introduced ourselves, and I didn’t know who he was! I knew every avant-garde composer in the world practically, but I didn’t know any film composers!

You’ve said that your music was influenced by one of your teachers, Arnold Schoenberg, the founder of the Viennese school and you also composed in the twelve-tone idiom…

I don’t anymore. I think that my work is now much more accessible but it’s rather interesting. For years I didn’t get any performances of my own work because I did films. In 1954 I did EAST OF EDEN, my first film. That year I had 5 major performances in New York, where I lived. The minute I did EAST OF EDEN I didn’t have any performances in New York for 20 years! That’s because suddenly I was a “film composer”. I didn’t get performances and since people didn’t hear my music for a long time, they’d say “Oh, he’s not writing any more.” And I had a whole pile of stuff. So I got very bitter and very upset by it, and thought to myself, “Maybe they think my music is commercial.” So I started to write music that was a bit more accessible than 12-tone music. And I began to like it much better, but I still had the schizophrenic idea of film music and then concert music. Well, about 5 or 6 years ago, a whole bunch of friends of mine said, “For god’s sake, stop being a schizophrenic, you have great passion and great technique, you write wonderful concert music, why don’t you combine them?” And I said, “You’re absolutely right, I’m tired of doing two things at once.” My work in the last 4 or 5 years is quite different now, much more accessible, although it’s not like film music generally.

FANTASTIC VOYAGE in 1966 had a very avant-garde score…

Today it’s still considered to be the most avant-garde score in films. It was interesting, I hadn’t done a film score in 4 years, I was living in Italy at the time, and I was conducting there. That’s what I do between films. Unlike the other composers, I will take off anywhere from one to 4 years and do my own work. FANTASTIC VOYAGE I did after 4 years in Italy. Richard Fleischer was the director. The sets were fantastic. I went there and I read the script and I thought it would be fabulous. I played some of my concert music, and Dick said, “That’s exactly the kind of music that I want.” That’s why I wrote this very wild kind of music and orchestrated everything myself. A lot of people in Hollywood were very jealous; they couldn’t understand what I had done because they had no tradition in that.

Living in Hollywood sounds like an adventure…

Actually, it’s not an adventure at all. Hollywood has no tradition, it has no identity. Los Angeles is a series of small cities, connected by freeways as opposed to New York or Chicago, or Vienna, for that matter.

Do you see yourself as specializing in sequels? You did STAR TREK IV, ROBOCOP II, and 3 of the PLANET OF THE APES films. BATTLE FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES has a very effective march, the main title…

The reason why I didn’t do the first ones was that very often when the first ones were done, I was not available. I was either doing my own work or I wasn’t in the city, or living in New York, or teaching at the university, and so on. When I came back, the directors would say, we’ve got the second one, would you like to do it? And I’d say, sure. That is why I did a lot of the sequels but not the originals.

The march in BATTLE FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES was based on some of the music that I wrote for the second APES film, BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES, which is the real science-fiction one. That was also a very, very avant-garde score at the time. But again, it had nothing to do with the theory of the 12-tone music; it had to do with something that fit the film. My favorite film scores are usually ones that may have even stolen things from other people, but they worked beautifully for the film, and that’s the important thing.

You won an Academy Award nomination for STAR TREK IV. I particularly like a cue called ‘Crash-Whale Fugue’ – it has a very baroque style trumpet motif…

It’s interesting, because that whole film was kind of fascinating. I thought it was the best of the STAR TREK films. It was very well directed by Leonard Nimoy, who was a friend of mine at that time. Unfortunately, in the script it stated that I use the original theme of STAR TREK in the main title, which I didn’t like. I did an arrangement of that and Leonard Nimoy said, “From then on you do your own music, anything you want that fits the film.” So I did the end title, which was very big, but was not based on the STAR TREK theme, it was my own theme. One of the parts of it was this fugue based on the whale; I thought the whale was so noble that I decided to do a baroque kind of thing on it to celebrate the living of the whale. When we heard all the music, Leonard Nimoy said, “You know, I must say, I really like your music so much better than the theme, let’s have another session and let’s re-do the main title and do your own music.”

There’s also an interesting cue called ‘Hospital Chase’… It’s an unusual chase theme, it’s like a polka.

It’s like a more classical version of Charlie Chaplin. I told Leonard Nimoy that’s what I wanted to do. He just loved it. With my technique of music they always asked me to do dramas, fantasies and so on, I wanted to show that I can do humor also. In ROBOCOP II there’s a cue called ‘Robocop Memories’. It has an interesting instrumentation with voices and bassoon or bass clarinet… The interesting thing in that score was that I was writing a violin concerto that had been commissioned, I was starting to sketch it, and I wanted to put 4 female singers in the violin concerto, but not like a chorus. They were sitting with the woodwinds, the flutes and clarinets. And they would not sing solos. They would sing in such a way that you would wonder, “It sounds like a human voice.” So I thought, “I may as well try it out”, and that’s when I started to use 4 female singers. I thought it worked wonderfully for the film, and it worked really well in the violin concerto!

For KEEPER OF THE CITY you used a very strange sound…

Yes, I tried to use a kind of church chant, so I’d be able to distort it, because that I was dealing with a crazy character, he was a kind of killer in the film. That was a television show.

The cue ‘Donetti Dies’ is a very effective 54-second cue. Is it a challenge for you to do such a short cue?

Always, yes. I wanted to say everything in 54 seconds. Sometimes you have to say it in 10 seconds! You don’t get that in classical music and that’s the kind of beauty of the process in film music.

You won a Golden Globe award for THE LORD OF THE RINGS. There is a cue called ‘Helm’s Deep’, it’s seven minutes long, I call it orchestra furioso.

I’m sorry that you did not hear it on the CD because we remixed it completely. It’s just wonderful now. I played it recently for an audience at Yale University. They just went crazy, they loved it, and they said it would be wonderful if you made it into a concert. I’m making a concert suite out of it. The male chorus sang a strange alien tune, in alien words. I made the words up. They also sang “Dranoel Namnesor,” which is my name spelled backwards!

I used just one or two electronic effects in the entire score. To me, electronic music is wonderful only because it can give you sounds that you can’t get with an orchestra. I don’t like electronic music in most Hollywood films, because they try to imitate an orchestra. But I did some very odd kind of sounds that you couldn’t possibly get with an orchestra. The film wasn’t very good, which was too bad, because the script was just wonderful. Also, when they put out the LP of the score, the LP could not take the aesthetics of the way the music was performed. That is why the CD is quite extraordinary.

You won two Academy Awards for adapting BARRY LYNDON and BOUND FOR GLORY. What makes it so interesting for a composer to adapt music to a film, and what was your working relationship like with Stanley Kubrick?

Stanley Kubrick called me and said, “I’ve completed a rather interesting film and I’d like you to arrange the music for me. Have you ever done arrangements for a film?” I said no. He said, “I’ve picked out all the music, but you’ll be able to conduct it with the London Symphony, and we’ll have some fun”, because we hadn’t seen each other since New York, we practically grew up together. So I said sure.

I came to London, I looked at the film, and I didn’t like a lot of the things that he had picked, although there were some that I did like. We argued and we talked and we argued, and so on. I won about 50% and he won about 50%. I did for example an arrangement of the main theme, the harpsichord, into this big kind of thing. Originally he had picked the theme in harpsichord. And I said, “It doesn’t fit that sequence.” He said, “It’s only harpsichord.” And I said, “Let me make an arrangement for it.” We argued. And finally he said, “Hah! It’s gorgeous!” We kind of liked each other, but we won’t work with each other again…

BOUND FOR GLORY was even more complex, because it involved music that I had had no experience in at all. Pop music from the thirties, folk music, but at the same time the score was rather interesting and different. The score had nothing to do with the songs whatsoever, except one or two themes. They had to do with the drama of the picture, with the relationships…

Now it’s interesting because I couldn’t get a nomination for the Oscar on the grounds that this was an original score, because there were 40 songs in the film! Despite the fact that there were 40 minutes of original music in that film! So I got the adaptation nomination and I got the Oscar for it, which is kind of funny because most of it was really original.

What is your working relationship like with your orchestrator, Ralph Ferraro?

Ralph Ferraro was a student of mine in Rome when I lived there. He was a percussionist at that time; I taught him all about music. I met him in rather an odd way. It was the first time I was conducting there, I had a little book with Italian, and I didn’t speak Italian at the time. I began to tell him, “Play so-and-so,” I was turning the pages of the book to find the translation that I wanted, and he looked at me and said, “I’m from Connecticut, I’ve been living here for 14 years!”

We became good friends, I became his teacher, and then I had him come over (to the States) and he became my orchestrator. My orchestrator in Hollywood is different from most orchestrators, in the sense that I do everything with such detail, that even if the orchestrator is sick or can’t do it, I just send my sketches to the copyist and the copyist can copy the whole thing. And now of course he knows my style in films so well, so when I say “brass”, he knows exactly how I do brass. He is superb.

Can you tell us how you feel about film music and classical music?

Well, as I said earlier, film music cannot be compared to concert music. It’s not that it’s not as good, it’s entirely different. Its function is entirely different. The process is entirely different. The process of film music involves drama, what fits the film. I did a South African film once which was never released. It’s called CIRCLES IN THE FOREST. It was done many, many years ago. A wonderful film. I recorded the music in Munich with the Philharmonic. The score was one of the best scores I’ve ever done. But it’s also a series of sketches for several works that I was writing at the time, although I wouldn’t sacrifice the Hollywood score for the sketches that I’m doing…

What are your favorite scores and what directors did you like working with the most?

Well, Kazan of course. Fleischer and FANTASTIC VOYAGE. My favorite scores – not including mine – are Benny Hernnann’s score for PSYCHO… JAWS… I think GONE WITH THE WIND is fabulous, even though these scores have entirely different styles, they really are sensational scores. Jerry Goldsmith’s score for PATTON – I think he’s one of the best composers in Hollywood. And I like EDEN too, I must say! (Laughs).

It’s funny, because I did several first films with directors – I did the first film for Robert Altman, it was called COUNTDOWN. But Jack Warner was the head of Warner Bros., he didn’t like the film, it was much too modern for him, people talked at the same time and he didn’t like that. They just buried the film. It was a masterpiece. I did the first film for John Frankenheimer, I did the first film for Martin Ritt, directors like that.