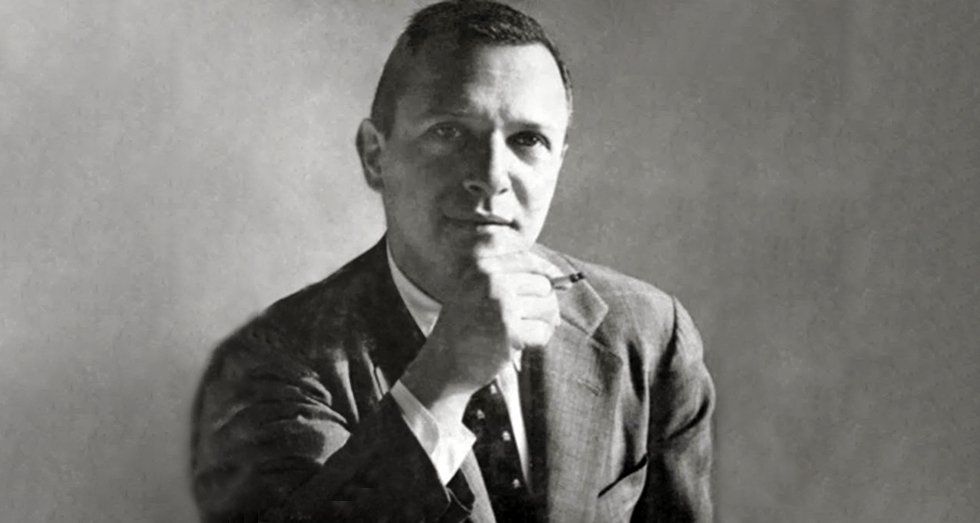

An Interview with Kenyon Hopkins

Film Music Notes: Summer 1957 Vol.XVI / No.5 / pp. 15-16

Copyright © 1957, by the National Film Music Council. All rights reserved.

This interview was originally broadcast over Gideon Bachmann’s weekly radio program FILM FORUM, sponsored jointly by CINEMAGE MAGAZINE and Fordham University, and heard in New York every Sunday at 9 P.M. over Station WFUV-FM (90,7 mc).

In the past year you have written your first scores for feature films – BABY DOLL, TWELVE ANGRY MEN and THE STRANGE ONE. Previously you had been writing for documentaries and industrials. Did you find the adjustment difficult?

No. I have always liked dramatic music, and this is just an extension of the technique used in non-theatrical films. The basic difference is that the dramatic elements in features are much stronger, and the music has to conform,

When you say conform, do you mean that it has to go along with the dramatic development of the visuals?

To a certain extent. Sometimes the most dramatic thing is to play something contrasting. For example, after the fire in BABY DOLL there is an immediate cut to a saloon, where Eli Wallach is in quite a dither about the burning of his cotton gin. I used a juke box as a background to the violent scene.

What is your attitude toward structure in writing movie music?

I’m inclined, perhaps because of my background, to select thematic material which I think will fit characters and situations, and develop it according to their needs. Again in BABY DOLL, you can find the main title theme in the end title; you can hear that theme in one type of development or another almost any where in the score. The average person might have to listen twice to hear it, but it’s there.

This raises a standard question about movie music. Should an audience be aware of it while looking at a film?

I think this depends entirely on the type of film. Certain producers and directors – for instance, Kazan – allow for music; they pre-plan so that music takes a part in the whole work, and then music is audible and makes dramatic sense. There are other producers or directors who don’t make such allowances. When they finish a picture they say “there is a weak spot; we need music there”. But when you get in the mix, they say “now, not too loud on the music, it’s just got to be a mood”. In other words, the composer is supposed to supply what the director didn’t put into the picture in the first place.

I’m often disturbed when something dramatic in the music marks a dramatic point in the film, because suddenly I am aware that this is a film, and part of the vicariousness of the experience is taken away.

There have been long arguments about this. We have all kinds of rules as to where we start and stop music. For example, a composer of the older school will tell you, you should never start music on a close-up, because it sounds like violins playing over the shoulder of the person you are looking at. But in TWELVE ANGRY MEN we deliberately started the theme on the boy’s face and it worked out very well. It’s quite unusual, starting without music. However, Sidney Lumet, the director, having come from television, is used to techniques that are a little bit different. He’s a fine director, one who does a great deal of pre-planning. The writer, Reggie Rose, gave us a shooting script that they handed right over to me as composer to work from, because it hadn’t been changed enough to even make a new timing.

Are there other instances where your music does not directly accompany the image?

In THE STRANGE ONE. Recently my album of THE STRANGE ONE furnished the whole background for a play on Studio One. The music was cut and placed so that it fitted very well. It is that kind of music because it strikes a mood. There are places in the film where I do dramatically catch things, but mostly the music enhances the over-all mood, which is pretty weird. I used a twelve tone technique which I don’t use ordinarily in a theatrical film.

How does composing movie music differ from composing for other musical forms?

It differs quite a lot. A composer usually sits down with a thought-out theme and develops it according to his own feelings for form. In scoring films, he has to limit himself by the stop-watch, not only as to the time allotted to certain cues, but also emotionally; the music has got to be in accordance with the film content. It is a restricting kind of composing. In TWELVE ANGRY MEN, I wrote a little fugue for a character that I thought would fit him very well. Everyone said it was one of the best cues in the film. We didn’t look at it with the picture at the time, and I recorded it. Then when we came to the mix to put it in the film, it didn’t vary enough with the mood of the dialogue to be useful. Thinking it over afterwards, I realized the fugal form I had selected already gave me boundaries, and therefore I couldn’t move freely with the dialogue.

This must be a constant problem in writing motion picture music.

That is true. Movie music is music that half-way develops and then the door slams and the cue goes out. But we did not score TWELVE ANGRY MEN dramatically. If you look at it and listen for the music you will see that almost nothing in the picture is ever caught musically. It is just played in a non-dramatic way to make a point – to remind the audience of the boy.

When this happens, it is on a sub-conscious level, I presume. Have you used a musical point in your other scores to influence the audience on a subconscious level?

In THE STRANGE ONE, the commercial melodies and the juke-boxes and the twelve tone chase which comes at the end of the picture are all related. The theme used in the final chase is the rune called “The Strange One”, used in a twelve tone form. If you listen to the album a couple of times, you can see the relationship of the whole thing,

Do you re-write the music for the album? I would assume that some adjustment is necessary when music has to stand on its own.

Usually we do a little editing. If we have a bridge where just one chord is heard to emphasize a truck falling over a cliff, naturally we don’t put the chord in the album. Mostly it is a matter of blending cues. We have long tails on cues in movies, so they can be mixed out. Then we just cut off those tails and put the cues next to each other, and generally speaking, you’ve got development. With me, anyway, the more complex developments come towards the end of the picture, and therefore the music makes sense in the order in which it appears in the picture.

Are there many buyers of soundtrack albums among those who have not seen the respective movies?

I don’t know. A reviewer of one of my albums said that people who had seen this movie would want the record. I don’t feel that way about it. In the picture the music has one function; in an album it has an entirely different one.

It would not be so different where the music was recognized as music in the original film, such as a musical. On the other hand, thematic music which one is not likely to be humming on leaving the theatre, because it didn’t stand out as music, would be likely to create a different response from a record. A theme heard by itself naturally rouses a different reaction than the whole conglomerate of sound and image.

You mentioned “themes”. I don’t want any confusion on that point, because what I think of as a theme might very well be a twelve tone succession of notes in many different patterns; maybe in inversion; maybe in retrograde; maybe in twelve different transpositions; and out of that I will pick simpler elements for simpler situations which might be recognized as a theme. But I don’t believe in the old-fashioned “beautiful” romantic type of melodic theme, played no matter what happens in the picture.

You mean your “theme” is more a frame of reference.

That’s right, exactly. It gives me a means of creating a form.