The making of Music for the Movies

"On-the-job-training" and "steep learning curve" are two phrases of modern parlance that have a special resonance for me, as I look back over the preparation of the material for CPO's recent release "Music for the Movies", devoted to film scores of my late stepfather Benjamin Frankel. As a student at the Royal College of Music, many years ago, I studied piano on the Performer's Course. Sadly, the study of orchestration and composition were not on the curriculum and I recall, with some irony, my consternation when I learned that the second-year theory exam included a paper on the former subject. The problem was solved in the end, not by the introduction of tuition in these areas, but by the discovery that there was an alternative paper which omitted such questions. My knowledge of the orchestra, therefore, (and still requiring much study), is based on listening, studying scores and reading numerous textbooks on the subject.

My motive in mentioning this may seem obscure but will become apparent during the course of this article.

Before entering into the details of the recording, it might be worth mentioning what I regard as being the genesis of the project. To elaborate, I must go back some sixteen years, to the moment when I first began my efforts to see a collection of Frankel film scores recorded.

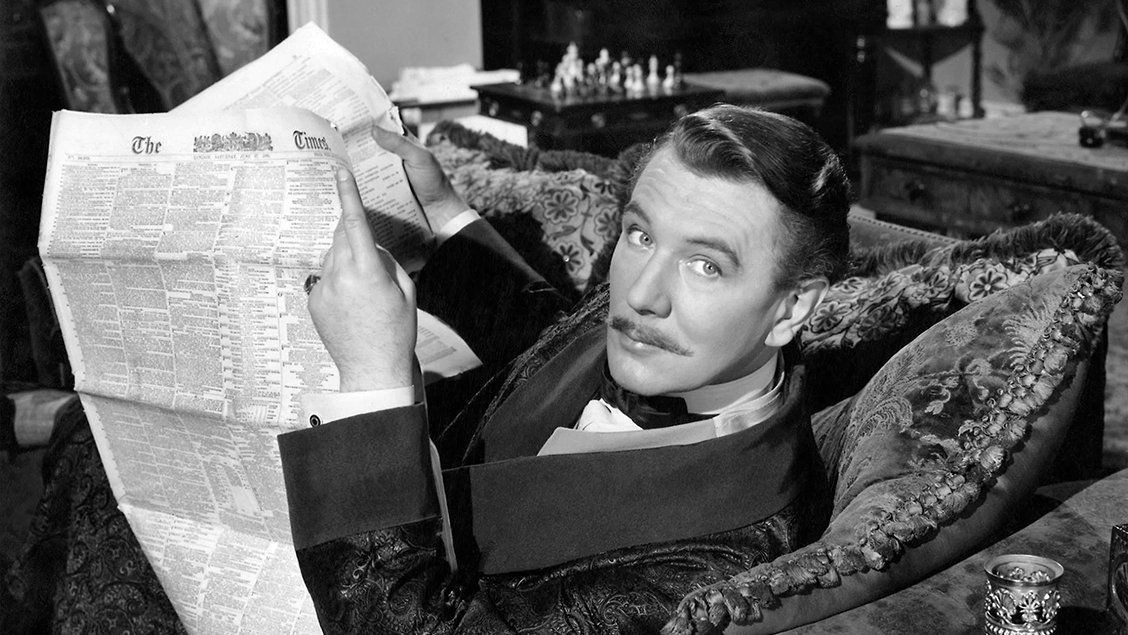

As I recall, it was sometime early in 1985 that I first saw the film Libel - a courtroom suspense drama starring Dirk Bogarde and Olivia de Haviland, directed by Anthony Asquith. He and my stepfather had been devoted friends and collaborated on a good many fine films (among them the above), starting with the most famous, probably, The Importance of Being Earnest. Other notable titles were Orders to Kill and Guns of Darkness.

While listening to the title music for Libel, I was struck by the instantly memorable, romantic theme and thought immediately that it was far too good to be heard only on the film's soundtrack. Then, not long after, I was browsing in a major London record shop and noticed a stand of LPs (the days of vinyl) devoted to film music, including various albums of individual composer compilations. Suddenly, the absence of any Frankel struck me as an absurd state of affairs, when considering his prolific and outstanding contribution to the field. It was then that I began the long - and often frustrating - process of trying to get an album of his film scores recorded. The problems were manifold. My initial thought was to see if a compilation of old recordings could be reissued under license from the various copyright owners. The available material was limited of course: there had been original soundtrack releases of (incomplete) scores from Battle of the Bulge and Night of the Iguana, occasional recordings of individual themes (notably, "Carriage and Pair", "The Lily Watkins Tune" and "A Kid for Two Farthings" theme") and some private acetates of original session material which my stepfather had kept.

This approach soon failed: the licensing of even a limited amount of material from, say, Battle of the Bugle was a prohibitive proposition; the quality of sound was too variable across the range of recordings and I also learned that original soundtrack material, if reissued commercially, incurred costly re-use fees of the Musicians' Union, unless the original fee had been negotiated to include a soundtrack release. The old private acetates mentioned above did not satisfy the latter condition, so were of little help. What to do next? If reissuing old recordings was not a viable option, then it would have to be a question of making a new recording. But only a few original Frankel manuscripts were extant (though enough to make a few albums). Like many composers, he had not maintained his own archives, doubtless in the belief that the material was no longer relevant once it had been dubbed to soundtrack, and the studios were little better at preserving scores, especially as many of them closed or merged, often discarding unique documents in the process. Nonetheless, the following scores survived: Battle of the Bulge, Night of the Iguana, Guns of Darkness, Curse of the Werewolf, Orders to Kill, The Prisoner, a selection from The Importance of Being Earnest (located in the BBC Music Library) and some cues from Trottie True (not much, out of nearly seventy feature film scores). Thus, a new recording could be possible - but who might produce it?

At about this time, someone told me of the sterling work that the record producer David Wishart had done in recording some British film music on his own Cloud Nine label, including scores by Bax, Vaughan Williams, Easdale, Schurmann and others. I made contact and was initially delighted to learn that he was highly familiar with the Frankel output and interested in the idea of a recording. Financial concerns soon raised their head again, however. To make a new recording with a major orchestra was a very costly proposition and without some major backing, it could not be done. Not only that, but the cost of preparing the materials (reconstruction of scores where required and also the production of parts from the few extant scores) was also a major issue. I then began to hunt around for financial backing in the business sector (it was a time when the arts were receiving a good deal of sponsorship). At one point, a private backer was interested but this route was scuppered by a change in personal fortune. Hope of the required backing seemed to be fading and the project had to be put "on hold". When the opportunities were there, David Wishart, in collaboration with the Silva Screen label, included some Frankel in compilation albums (a suite from Curse of the Werewolf on a CD of scores from horror films; the Prelude from Battle of the Bulge on a commemorative D-Day album). Still, however, an entire album of Frankel's film music was nowhere on the horizon. Then fate stepped in, with an unexpected twist, in the shape of the German label CPO.

I had always thought that my stepfather's film music - apart form being worthwhile in its own right - could provide a gentle way in for those wishing to approach his more demanding concert music. Yet, it was the latter which initially attracted the interest of CPO, during the early 1990s and which was to be recorded by them in an extensive and highly acclaimed series of recordings which embraced the eight symphonies, the string quartets, the concerti, and many other works. This, it has to be said, was what would have mattered to my stepfather, who regarded his film music as a means to an end - a living - and who was always dubious about the validity of film music when heard away from the films themselves. CPO, however, were always interested in the idea of recording some of the film music, once the major concert works had been completed on CD. So it was that in 1998 and 1999, the complete score of Battle of the Bulge was recorded ( honoured with a Cannes Classical Award at the annual MIDEM event in January this year). It should be said that this too might not have got off the ground had there not been the great good fortune to trace a complete original set of parts. To have engaged a copyist to produce a new set - bearing in mind the score is fully symphonic and some eighty minutes in length - would also have raised serious budgetary issues. Once the Bulge CD had made its mark, CPO now decided that they wanted to follow it up with a further film music recording.

After the drama and symphonic grandeur of "Battle of the Bulge", I was very keen to focus on another side of my stepfather's creative genius - his witty and tuneful film music. Even before "Battle of the Bulge" went into the recording studio, I had started preparing material against the day when a second recording might be confirmed. Thanks to the revolution in computer desktop publishing and with apologies to all those who used to earn or supplement their livings as copyists, I was able to produce printed scores and parts for Night of the Iguana, Trottie True and The Importance of Being Earnest. For the most part, as many would confirm, this side of the process is hack work, involving the slow and painstaking transfer of the written page onto the computer. (It may cause some mild amusement when I disclose that, so far, I was working with an old Atari STe computer, using the Steinberg Cubase and C-Lab Notator software programs!). Trottie True did involve some creative thinking, however: it seemed to me that Ben had kept just a few cues from the full score, which he felt, perhaps, could be put to use as a light-music suite. This is speculation but the basis was there nonetheless. I needed to do a bit of cutting-and-pasting and effect a few modifications to produce the eventual six-movement suite. I also made an arrangement for muted stings of the "Lullaby" from "The Years Between", a very attractive piece which existed only as a published piano solo. The real challenge, however, came with the need to reconstruct some of the music I felt was desirable for the proposed recording.

For a while, I had been experimenting with a number of themes from various films, among them The Love Lottery, Libel, Footsteps in the Fog, Portrait from Life, The Man in the White Suit, London Belongs to Me and A Kid for Two Farthings, all of which were ideal candidates for an album of light and melodious music. The simplest part of the procedure was the taping of the soundtrack from video onto an audio cassette. Then came the difficult part. Often, I would sit at the piano, listening repeatedly to a passage on the tape, and fill in the more obvious details first: melody, harmony and rhythm. Then came the real challenge - attempting to reproduce the composer's original orchestration ( where I would often employ the added aid of a synthesizer to approximate the sounds). Some aspects of this are fairly clear - solos played by the different instruments, a theme spread out in octaves among the upper strings and so forth. Background detail and doublings are another matter: these can be difficult to discern even with modern digital recordings but on scratchy old monaural soundtracks some details can disappear almost completely, especially if, as so often, the orchestra is heard beneath dialogue and other sounds. Many would agree that some doublings have to be inferred - oboes do not cut through loud orchestral tuttis really, though their presence must, in some subtle way, modify the sound we hear. Piano or harp filling in harmony can also be obscured quite easily, at least in terms of the individual notes they play. Here, I must pay tribute to Ben's clarity of orchestral style - he wrote astutely and economically for the orchestra, seldom indulging in the "all-but-the-kitchen-sink" approach.

As it was clear that I would not be able to reconstruct all the scores I was working on, for this one project, I settled on three in particular: the love theme from The Net (another Asquith film), So Long at the Fair (the expected "Carriage and Pair", with the addition of some other cues to form a longer, integral piece) and a personal favourite - Footsteps in the Fog. The main theme from the latter ("The Lily Watkins Tune") had been published as a piano solo and recorded by some of the light orchestras during the 1950s, but none of the original score survived. The complete score contains, I would estimate, about thirty minutes of music, some of it dark and dramatic. Not wanting to stray too far from my original plan (especially given that Night of the Iguana is a serious score), I focussed mainly on the romantic, melodious sections (with the odd bit of drama thrown in!). The final result was a four-movement suite which accounted for about half of the complete score, at about fifteen minutes. Now, I must confess to some necessary tampering. As many will know, film music does not - nor does it need to - follow an intrinsic musical design: it fades in and out, sometimes lasting a mere few seconds, sometimes far longer, according to the needs of the unfolding narrative. Mainly, Footsteps provided a number of more extended and cohesive sequences (the second movement, for example, following the original soundtrack precisely).

Elsewhere, however, it was necessary to compose some bridging passages, so that the continuity could be preserved and a satisfactory musical result attained. Thus, the title music is joined, via a linking modulation, to a later incarnation of the theme, followed by a bridge which leads to its reprise, then a short coda. The third movement provided a happy opportunity to link two contrasted sections ("Lily's Triumph" and "Motoring in the Country") with the minimum of effort: it turned out that the bar which finished the former section rested conveniently on the suspended dominant seventh of the latter's opening. Repeating the bar (which happened to make a balanced four-bar phrase) and resolving the suspension led perfectly from one into the other. The finale again required some thought. There is a point near the end of the film where the music stops and, after some short dialogue, the main theme is reprised for the last time. I experimented with various linking ideas (always, I must stress, based on the composer's own thematic elements), before coming up with one which seemed to join the two sections naturally. The last confession concerns the inclusion of a 'grand' (though short) Hollywood style coda, to compensate for the fact that, in the original, the music fades into nothing (that is, apparently, as one cannot know if this was the result of editing). Here again, though, the ending derives entirely from Ben's own themes and is, in fact, a kind of mirror image of the score's four-bar introduction.

Perhaps it is worth mentioning one or two circumstances which nearly caused the recording to be delayed, at the very least. I had sent the materials for Night of the Iguana, Trottie True, The Importance of Being Earnest, The Years Between and Curse of the Werewolf (the "Pastoral", included for its suitably romantic style), to the Queensland Symphony Orchestra and also to the conductor, Werner Andreas Albert, well in advance of the recording being scheduled. Then the original dates were postponed due to some oversight and I could not get a clear idea of when they might be reinstated, so relaxed my efforts on "Footsteps". Some months later, and without warning, some other sessions were cancelled and the project was on again, leaving only a short time to complete the work 'in hand'. The reconstructions of So Long at the Fair and The Net were done and sent off to Brisbane a shortish while before the sessions but... were mislaid somewhere at the other end and did not reappear to date. (They were only copies of course). As the sessions drew nearer and nearer, I was now struggling to complete Footsteps in time and also wondering whether to re-send the missing scores. In the end, and following an all-night sitting at my computer (now a PC, and using a program called Personal Composer), I managed to finish the task about four days before recording was due to commence. I sent off the score and parts by courier and, thank the stars, they arrived in time. As it turned out, the recording sessions finished with only a few minutes to spare , so the missing material could not have been done on that occasion after all (or had it been done first, something else would have been omitted instead). Bearing in mind that I had been engaged on reconstructing one of my stepfather's creative triumphs, I could only be thankful that I had only to do that and not actually write the music myself. My respect and admiration for him and others who work under such pressure of time and yet manage to produce something of stature had grown enormously.

And what of the final result? I awaited the edited mastertape in a state of high anxiety for nearly a year, before I could decide for myself if I had succeeded in my aspirations. I confess to some tears of relief and joy when I heard the reconstructed music from Footsteps: it sounded to me as if it was a faithful recreation of the original. I would never presume to swear that every last detail is accurate but, at worst, the result could be regarded as a mixture of recreation and arrangement - a compromise I decided I could live with.

All in all, a long-cherished dream has been realized and I hope that the new recording will not only appeal to existing Frankel admirers but will also win his music new friends, showing, as I believe it does, how complete was his musicianship, craft and artistic genius. Last, but by no means least, I hope that, were he around to hear it, he would appreciate this, my personal tribute to his memory, borne of the utmost love and gratitude.

Originally published @ MusicWeb International © 2002

Text reproduced by kind permission of MusicWeb Founder, Len Mullenger and E.D.Kennaway

Copyright © January 2002 E.D.Kennaway. All rights reserved.