The score begins over the Columbia Pictures logo, and is our first introduction to the main theme, played like a sweet lullaby on harpsichord, notes plucked as if by a child, gentle and unthreatening. We see Freddie, net in hand, run into a clearing of overgrown grass as he chases after a butterfly on a bright, clear day. As the melody plays itself out, and just a half-beat before the last note fades, Jarre drops the pretense of pleasantries with two gloomy notes of low brass, accented by single hits of xylophone as the title fades up. This creates a quietly somber and chilling beginning. When the harpsichord returns to flesh out the theme, it has become a short but painful musical sting, clipped by a restrained trumpet. When a solo clarinet restates the melody, it is transformed into a delicate pastoral.

The Collector

An Analysis of the Score to the Entire Film The Collector (1965) by Kirk Henderson

Since Maurice Jarre’s score to William Wyler’s THE COLLECTOR was first released on a Mainstream LP in 1965, other Jarre works have completely overshadowed it, and when the composer’s oeuvre is discussed, rarely is THE COLLECTOR ever mentioned.

Jarre’s own DOCTOR ZHIVAGO, which made such an impact the same year, became an albatross to overcome since everyone was looking for the next ‘Lara’s theme’. Mainstream Records re-released their original LP release of THE COLLECTOR on CD with no additional music from the film. Columbia Pictures owns the masters of the actual film score; Mainstream only the masters to its original LP release.

There are other reasons the score is not better known. THE COLLECTOR is a seductively depressing story and probably perceived as not the sort of experience one wants to relive by listening to the music. This is a shame, because Jarre’s score itself is very listenable, and ranks as one of his finest, most substantial works, more complex conceptually than his scores to LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and DOCTOR ZHIVAGO.

Spoilers lie ahead so if you have not seen THE COLLECTOR (and it is highly recommended you do), please return here after having seen the film, for what follows will certainly ruin the many surprises the film has to offer.

Maurice Jarre was the perfect choice to score this film. While not necessary considered, other possible composers like Georges Delerue, Piero Piccioni or even Malcolm Arnold might have come up with something interesting, but as will become apparent, Jarre’s scoring history was an ideal precursor to this psychologically twisted social fable.

The film was based on the best-selling book by John Fowles, notable author of such works as The Magus and The French Lieutenant’s Woman, two novels also made into films. The Collector tells the story of Frederick Clegg, a repressed bank clerk, who has become obsessed with a beautiful art student, Miranda Grey. He follows her from afar, keeps tabs on her daily activities and imagines in his own mind what life would be like if they were only together. When he wins a large sum on the football pools he purchases a house in the Sussex countryside with a deep hidden cellar, fixes the cellar up with sound proofing and dead bolts, and kidnaps Miranda in the hopes that once she is there, she will get to know him and fall in love with him. This is the scheme of a lunatic, and the outcome created by thrusting these two characters together is made compelling in the hands of writer Fowles, who presents the story from two points of view. We initially get Freddie’s first-person account and then Miranda’s own version via her daily journal, which describes, with horror and frustration, the insanity of her captive situation.

The book is remembered for its two distinctive personalities not only at odds with each other on a personal level, but also from completely opposing ends of the political and social spectrum. Conflict between the British social classes has long been a staple of the literary world and the view Fowles gives us by the use of this very unusual premise highlights the differences to the point of maddening clarity. Educated Miranda, the daughter of a well-to-do physician, finds herself face to face with working class Frederick, a man to whom she normally wouldn’t give the time of day. Suddenly she is living on his terms, discovering up close and in the most frightening way, how impossible the situation between the classes really is.

Although this story has nods to Bluebeard and Beauty and the Beast, its social conscience goes deeper and has more in common with Shakespeare’s The Tempest. In Fowles’ book, Frederick is a monstrous slave Caliban to Miranda’s Shakespearean goddess, now trapped underground, not unlike the social relationship between the descendants of upper-class Eloi and working-class Morlocks in H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine. In The Collector the roles are reversed, with upper class Miranda below ground, and working-class Frederick above. The outcome of the story gives us a pessimistic view of two classes at odds, their separation so distinctive that only the insanity of a prey versus predator relationship could be the end result. Clearly, there is a cautionary element to Fowles’ story.

Although not all of Fowles’ observation of differences between the classes made it into the film, it isn’t ignored, and Jarre’s ingenious score, which focuses primarily on the state of mind of Freddie, becomes a musical metaphor for this social tyranny and mental anomaly.

Freddie plunks his net over a resting butterfly, and the melody line is developed with flute and sharp rhythmic accents of harpsichord. These accents might have been achieved by pizzicato strings, but the harpsichord carries with it notions of a very proper past and a touch of stuffiness. It is an instrument that no matter how forcefully played, feels restrained. The harpsichord is a part of Freddie’s mind, reflecting his inhibitions while maintaining a staid sense of beauty, and as the theme continues, its singsong playfulness suggests a ride on a merry-go-round.

The melody attempts to grow in orchestral color but only briefly lets loose with childhood glee before reigning in, not giving in to unbridled expression. Since this is the harmonic metaphor of Freddie’s mind, if we follow the music closely, Jarre rewards us with a good understanding of not only Freddie, but Miranda as well.

The harpsichord used in THE COLLECTOR was a double harpsichord, and according to the liner notes of the Mainstream CD release, it was difficult to keep in tune and hard to play. Jarre takes advantage of qualities unique to harpsichord and utilizes them throughout the score; under his baton, the harpsichord becomes surprisingly flexible. There are moments where the instrument is a burst of joy, a run of fresh air, a chilling coda, a delicate seduction, or the unexpected lead of a jazzy rhythm. It wasn’t the first or last time the composer made use of harpsichord in a score, but it was the one where his use of it was the most unconventional and profound. Jarre’s substantive use of it for THE COLLECTOR has no equal.

Some who follow film music sometimes complain about how few themes are explored in contemporary scores. One theme is written and beaten to death. Perhaps the same could be said of Jarre’s score, for there really is only a single theme – ‘the collector’, but by being transformed in such a myriad of ways it becomes a text book of orchestral and harmonic invention.

In conception and execution, Jarre’s collector theme and its orchestration is the musical equivalent of the end product of arrested emotional development. To Freddie, his grand scheme to kidnap Miranda is not only a dream come true, but is as cool and hip as a teenage boy on his first date with a pretty girl. With the money he won, he’s gained the power and potency to force a relationship between he and Miranda, yet his emotional maturity is stunted like that of an infatuated young boy who just got dad’s car but doesn’t know what to do with the girl once he has her.

Freddie, played with keen observation by Terence Stamp in one of his early roles, discovers a country house by accident and investigates the property. He discovers the deep cellar and his eyes grow wide with the birth of his insane scheme. Jarre underscores the shot with pipe organ, soon overtaken by ‘audio ambience’ - a tape loop created from a recording of glass harmonica, played in reverse and given an almost painful edge with a slow undulating flute. Not so much music as sound, is the representation of a sick mind festering in isolation, a theme for insanity.

After a few seconds, the rhythm of a single note of violin breaks the spell and becomes the cerebral cradle of the main theme, repeated simply and quietly on harpsichord as Freddie tells us in voice-over about the plan he thought he would never go through with. The rhythm pulls us in and gives a sense of security. We don’t really know what Freddie has in mind, but whatever it is, the soothing pulse of a single violin and delicate harpsichord suggests there is nothing to fear.

When Wyler cuts to Freddie later spying on Miranda from his van, the glass harmonica ambience returns to remind us that in spite of the serenity on the soundtrack, what is about to follow is not going to be all that pleasant.

Freddie watches Miranda from across the street as she leaves art school and innocently strolls the streets of London. Jarre’s theme, at first playfully reworked for sax and reeds, suggests the harmony and tranquility of the beautiful art student. Following a reprise of the now chilling glass harmonica ambience it becomes a jazzy rhythm with a cool edge as Freddie pulls his van into traffic and begins to stalk her.

Jarre’s use of a jazz rhythm here is effective and telling. Brushes whisk a dandy tempo on cymbal, while double harpsichord picks away a variation of the main theme, effectively giving the forward momentum a downward sense. Brushes also give the sequence a sense of excitement, but the harpsichord won’t allow us to forget the twisted logic forming the foundation of the story. Freddie has been planning this moment for some time and the music displays his giddiness. The jazz element adds a sense of “cool” to this event. In Freddie’s mind, kidnapping Miranda is the coolest, hippest thing he’s ever conceived of, and the fact that he has the money to carry out his mad plan allows him the luxury to view his act in that regard.

Unlike the book, which begins with Frederick describing how he came about his plan, and describing it all as history, the film starts with the kidnap about to take place. The concept of a jazz ensemble being led by a harpsichord is an unusual one, but Jarre has a reason for it. Placed together, these two musical worlds are out of their element, and the melody carried by sax creates a sense of a lustful preoccupation. Freddie is a driven man, with one goal in mind, to kidnap the vision of his dreams.

Unlike jazz, Jarre’s music is fully structured, making no allowances for improvisation, and the harpsichord will not allow the true nature of the freedom of jazz to take the melody and run. The jazz here is merely a stitched-together fantasy in the mind of a sick man, a tapestry with the undercurrent of a misplaced harpsichord weaving its menacing threads as a malevolent picture takes form.

Most of this music of Freddie stalking Miranda is not on the Mainstream soundtrack, and this is some of the most interesting music in the score. It works on many levels. It helps create character, set a mood, delineate opposite worlds in musical terms, build tension, and mark a major event soon to take place. The stalking music also works simply to underscore a man on the prowl.

While the jazzy rhythm sweeps us into the story and Freddie starts the engine of his van and pulls out to follow Miranda, a single clarinet renders its own version of the main theme, kept in control by the unchanging note of harpsichord. It becomes a ticking metronome ready to explode.

As Freddie holds his breath while pouring chloroform into a handkerchief the theme falls down scale as if the harpsichord was being sucked into a drain. Musically and psychologically, this works well, beautiful but unsettling.

Jarre stops the score just before the kidnapping and doesn’t bring it back until Freddie has overcome Miranda with the chloroform. After the deed has been done, an undulating low clarinet phrase develops what appears to be a new theme. Yet this quiet sense of alarm is nothing more than a variation on five notes from the main theme.

We also hear for the first time, a variation that might be called the ‘distress and excitement’ theme. We see Freddie’s van head away with his fresh catch and later pull up next to the cellar entrance of his country house. This theme, a mix of pacing reeds with added light pound of bass drum suggests a worrisome excitement. On the one hand, it reflects the excitement of Freddie’s catch, but it also embodies the distress we know the “caged animal” Miranda will soon experience. It too is a variation on the single theme, now reduced to a repetition of three notes.

Once Freddie has moved the still unconscious Miranda from the van to the inner cellar and placed her on a bed he has provided, Jarre chooses Freddie’s inner joy as the element he will follow musically. He does this with a sense of harmonic delicacy. There is no rape in mind here. Freddie carefully pulls Miranda’s skirt over her exposed knees, and gently removes a strand of hair that has gotten caught in her mouth.

An easy choice here would be to score the moment with darker tones, but Jarre chooses to play this against the most peaceful rendition yet heard of the main theme. The flute, reeds and harpsichord create a wistful sense of glee. This plays out until Freddie switches off the cellar lamp and stares down at her, his face a rim-lit black shape, a suggestion of satanic evil. All the more chilling is a reprise of the piercing throb of the audio ambience, the insanity theme come home to roost.

Yet, the joyfulness is expanded when Freddie locks up the inner cellar and runs into the big house. The main theme is reprised, but this time the lead up to it is different. As he washes his face in the kitchen, a spiraling group of woodwinds suggest the audacity of what he has just done, while an undulating downscale fragment on piccolo, gives the moment a sense of unease. When Freddie looks out the window and smiles, the score takes a dramatic turn. Accompanied by a rumble of thunder on the audio track, flute and reeds graduate from downscale to upscale, ending up in a jubilant variation of the main theme, as he runs out into the rain, laughing wildly. There will never be another moment of such bliss in the rest of the score, and the music is so pleasant, it’s a shame it wasn’t included on the soundtrack.

It should be said that Jarre’s concept for the music of The Collector has precedence in an earlier score, LES YEUX SANS VISAGE (Eyes Without a Face), a 1959 French thriller directed by Georges Franju. In that film, a physician kidnaps beautiful women to graft their faces onto the face of his daughter, who was disfigured in a car accident he caused. Like that story, the score is an insanity in itself, a fusion of jazz and the rolling rhythms of a merry-go-round theme, also performed on harpsichord. In this regard, its contrasting musical styles are very similar to THE COLLECTOR. The earlier score, while effective, lacks the depth, subtlety and variety of the later work. In LES YEUX the unique score gives the film a surreal, poetic quality, enhancing Franju’s moody visuals. Jarre’s score to THE COLLECTOR is more like the harmonic blueprint of the psyche of Freddie and Miranda.

As Freddie lies in the rain, the camera zooms into his face and director Wyler dissolves to a black and white flashback where Freddie’s aunt pays him a visit at the bank where he worked as a lowly office clerk. She announces to Freddie and his teasing co-workers that he has won the football pools and is now a rich man. The scene is accompanied by glass harmonica ambience, underlying the fate that will allow Freddie to both conceive of and realize his bizarre scheme.

After the flashback, when the score returns, we are in the cellar as Miranda awakens. The first thing we hear as she looks at the dank ceiling of what is to be her new incarcerated home, is the Dies Irae, the ancient black mass that has been used countless times to underscore the satanic. Jarre does not give it to us straight, backing the piece with a single note of searing glass harmonica, which melds the ancient horror with Freddie’s contemporary version of it.

When Miranda realizes she has been kidnapped, Jarre brings his main theme back, but only in fragments, starting with a blaring trumpet and compounding the terror with a trill of piccolo. As Miranda inspects the cellar, finding a complete wardrobe, including undergarments, all brand new, the distress theme plays in spurts as she discovers, perplexingly, that in spite of being a prisoner, she has all the ‘comforts of home’. During much of this, the harpsichord takes a back seat, only recurring as a brush of keys when she opens some drawers to inspect the contents. This altered use of harpsichord is a suggestion of how Freddie’s insanity is perceived by Miranda. The harpsichord here is not like the structured playing associated with Freddie. Miranda is still ‘in the dark’, and so the harpsichord is there but undeveloped.

Samantha Eggar, who plays Miranda, couldn’t have been a better casting decision. In 1965 she was a stunning British beauty in the classic sense with a mane of red hair, a porcelain face textured with subtle freckles, perhaps not exactly as described in Fowles’ book but certainly reflecting the sense of purity and refinement that could inspire a young man’s obsession. Eggar’s physical beauty is only part of what she had to offer. She provided a full-blooded, emotionally rich Miranda, fiery, obstinate and defiant, one of the finest performances of her career, and for which she was deservedly nominated for an Oscar as Best Actress of 1965. She was also good with comedy, appearing alongside Cary Grant in the 1966 WALK, DON’T RUN, his final film. She was equally effective in THE MOLLY MAGUIRES (1970), about coal miners in Pennsylvania, and remarkably scary in David Cronenberg’s THE BROOD (1979). It was her performance in THE COLLECTOR that made her a star.

The first meeting of Freddie and Miranda is played without score, as are most conversations in the cellar. Music in this first meeting would have been overly melodramatic. After a knock at the cellar door, Freddie enters like a butler, with a tray of food. Soon we learn along with Miranda, that he is in love with her and has kidnapped her to allow her the time to ‘get to know him’. Naturally, she is decidedly upset, and all her pleas to reason are for naught. He is resolute. She offers to stay a week, but he has a different time frame. “Can’t you see?” he tells her, “I haven’t gone to all this trouble just so you’d stay for one week more.”

Ultimately, Miranda realizes the police must be searching for her. The whole of England must be searching for her. Freddie agrees. “Well, sooner or later they’re going to find me,” she explains. “Never,” states Freddie, ”because, you see, they’re looking for you alright, but… nobody’s looking for me,” and with that Jarre brings in a chilling organ accompanied by a thump of drum and low reeds, a comment on Miranda’s realization that because Freddie understands what a nobody he is, the chances are, she will not be found. Despite Miranda’s fear, Jarre quickly shifts the harmonic point of view back to Freddie as he turns to leave, using a soft variation of the now familiar theme, played gently on clarinet, as pastoral as ever. This effectively allows the audience to feel sympathy for Freddie, who, despite his insane act, is a character to be pitied.

Next morning Freddie returns to hear Miranda groaning. Of course, she is using the ‘I’m sick and need a doctor’ ploy in an escape attempt. “I’ll get a doctor!” he exclaims, and she hears Freddie run up into the upper cellar to swing open the outer door. She can see her route to freedom and runs into to the upper cellar only to be stopped by Freddie, who had suspected her ploy. Her POV of him looking down at her with distain triggers a thumping shudder of deep brass and woodwinds momentarily paused when she slaps him across the face before returning to the lower cellar and slamming the door.

A hesitant clarinet reflects the tension between the two, and the full main theme returns after Freddie follows her back into the inner cellar. “Alright,” he says, and the music ends to allow their words to carry the scene alone, “I’ll tell you when you can leave, but only under certain conditions.”

Among the conditions, Miranda must promise not to try to escape and to start eating, since the trays of food he has brought have remained untouched. At last, when an agreement of one month is reached, he says, “It’s alright. It’s agreed!” A starved Miranda begins to inhale the breakfast, and Jarre imbues the scene with relief using an airy take of his main theme, cheerfully incorporating the harpsichord to trace the melody line taken up by flute.

Freddie leaves so she may eat in peace, and steps outside to do an imaginary tightrope walk on the low wall of the walkway that leads to the yard, an action matched by the merry-go-round interpretation of Jarre’s theme, both gleeful and childish, complete with a dashing rhythm of brushes and wooden xylophone. He comes to a balustrade end and crouches down as if ready to spring to the other side, but gives up. This cues a shift to the refrain of the melody line on harpsichord when we return to the cellar and see Miranda contemplating a month of captivity. A soothing clarinet suggests the tension and fear have subsided while the light harpsichord adds a nursery rhyme tone. This lower cellar is, in a sense, Freddie’s nursery, where he comes to play. After Miranda counts the bricks on one wall, determining 28 days, we dissolve to her a week later, painting out the bricks she has numbered that lead to a large brick that reads “Freedom Day.”

Once the story moves into the cellar and stays there, Jarre’s music is primarily used for transitions and the passage of time. Now that Miranda is counting the days, making half-hearted attempts to talk to Freddie, both of them are keeping their emotions in check. We learn much about the characters at this point. Miranda suggests Freddie do something to amuse her and Freddie is too shy to tell a joke until she threatens to tell a dirty one. “I know one that’s filthy!” she tells him. He complies with a simple joke amusing enough to make her smile.

Freddie brought Miranda to this place with the intention of her getting to know him, and so if he sits around and says nothing, she will not get to know him. It’s interesting that the way she coaxes conversation out of him betrays her snobbery. Likewise, his response to the idea that someone like Miranda might actually know a dirty joke or expect him to tell her one, reveals how little he understands about women and, for that matter, anything outside his own social orbit.

What follows when Freddie allows Miranda to come up to the main house and take a bath, is a sequence where music will dominate. Freddie ties her hands and checks to make sure it is all clear outside before he lets her come up to the front yard. Low woodwinds begin the cue, suggesting that, in spite of her thrill to get out of the cellar, an undercurrent of tension has returned, and Miranda, hands tied, is more vulnerable than before. When she steps up to ground level and takes a breath of fresh air, an arpeggio of harpsichord ignites the collector theme. This will be one of Jarre’s most intense cues, as well as an impressive display of the harpsichord’s range.

Rarely has a film score provided as much psychological structure as Maurice Jarre’s music for William Wyler’s THE COLLECTOR. If we had been paying close attention to the score we would have known all along about the film’s inevitable conclusion.

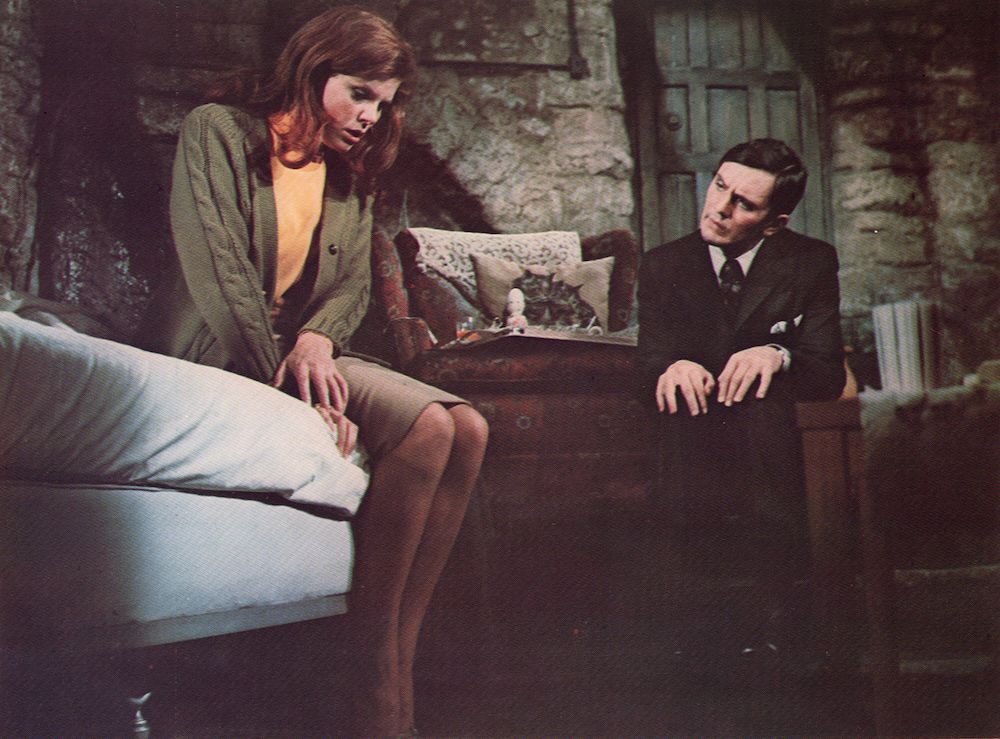

Freddie has finally allowed Miranda to come up from her ‘prison’ to take a bath in the main house. Her hands tied, she steps to ground level and takes a breath of air. “Marvelous!” she says, inhaling deeply, the harpsichord initially mirroring her exuberance with bright arpeggios. In this scene the harpsichord has the widest scope of any of its many appearances throughout the film, first with the aforementioned arpeggios reflecting Miranda’s POV, as did the brush of keys when she first awoke in the cellar. This is followed by a series of uneasy jabs until it builds to a shuddering rhythm. Both Stamp and Eggar give carefully controlled performances here, with Jarre’s score augmenting their psychological states.

Per her request, Miranda and Freddie walk through the garden, but she notices he has fixated on her and slowed his pace. Seeing Miranda outside in the warm evening light he is overcome with passion and begins rubbing her arm. Miranda’s relaxed harpsichord is overtaken by Freddie’s structured and steady style, with delineated notes adding unease. Freddie turns the terrified Miranda towards him and starts running his hands through her hair (perhaps a prelude of something darker to follow) and the harpsichord begins a pulsing rhythm with added reeds laying over ominously, imbuing the moment with fear. The cue cuts abruptly when Miranda screams and Freddie covers her mouth.

When they get back into the house Freddie is embarrassed by what just transpired and tells Miranda it won’t happen again. Jarre gives us a subdued reprise of the pulsing rhythm we just heard in the garden, which in itself is an interpolation of the collector theme, and keeps the moment on edge. Then, as Miranda says, “If it ever does happen again, and worse, don’t do it in a mean way or use chloroform,” the collector theme flows beautifully and inexplicably, yet only for a moment, abruptly ending on a downward tone. Then Miranda adds, “I shan’t struggle. I’ll let you do as you like.” Once the silence becomes unbearable for Freddie, she completes her comment with, “But, if it ever does happen again, I’ll never respect you. And I’ll never ever speak to you ever again.” The score held back exactly where it should have, allowing Eggar’s performance to pull all the punches.

A while later, Freddie sits in a chair outside the second-floor bathroom and once he hears the rippling of water as Miranda steps into the tub, he darkly recedes into deep thought. Jarre’s pulsing garden variation is now subdued, sketched out with low reeds, suggestive of the mystery that is Freddie’s mind.

Cutting outside the house, director Wyler adds a scene not in the book to add dramatic tension. We see an older man has pulled up in his car. He gets out and heads to the front door. His prowling around to find the owner is accompanied by nasal clarinet and accents of piccolo, adding a touch of nervous humor. When the doorbell rings, Freddie springs up and dashes into the bathroom to gag and bind the screaming Miranda.

The distress theme is played on reeds and flute, given a savage edge with kettledrum and fitful starts and stops to mirror the action as Freddie secures Miranda to a drainpipe. When he steps to the window to ask the man what he wants, the score subsides, allowing the tension to build on its own. The man is a neighbor, come to get acquainted.

A nervous Freddie lets the man in. Upstairs, Miranda turns on the tub faucet with her foot to draw attention. The water begins to overflow, eventually pouring down the stairs and noticed by the neighbor. Nervous Freddie scrambles into the bathroom, shuts off the water and tightens Miranda’s bonds. When he comes back out, he smiles sheepishly and tells the man, who is halfway up the stairs, “It’s my girlfriend.”

“Why didn’t she call out?”

“She was embarrassed,” Freddie tells him, and then, “you know how it is.”

The old neighbor turns, adding, “I remember how it was,” and leaves.

The lack of score allows the audience to feel the story has been put on hold while Freddie deals with a nosy neighbor. A complete fabrication by director Wyler, the scene works in Freddie’s favor. Even though we want Miranda to escape, the lack of music keeps us tense because, as in any good crime drama, we also don’t want the lead character to be found out. Both movie and plot are developed in this scene by showing Miranda’s intent to escape and Freddie’s ability to think on his feet. It also sets up their next confrontation.

When the score returns, Jarre allows the story that matters to continue. When Freddie steps into the bathroom, reeds and harpsichord sketch out the collector theme in an altered merry-go-round version of it as Freddie unties the terrified and humiliated Miranda. The cadence is determined but slower. Jarre’s harpsichord continues to form the rhythm, a variation of the garden pulse, suggesting Miranda, naked but for a towel, is her most vulnerable. The audience knows Freddie may be a dark character, but he’s not a rapist, so it’s not surprising the score maintains the nursery rhyme approach we have associated with his childish nature when Miranda’s towel accidentally drops and he merely lifts it back and looks away.

What follows is a key scene, illuminating the film’s title and the nature of the main character. It begins when we see Miranda step from the bathroom, refreshed and clean, her hair wrapped in a towel, accompanied by a quite ornamental version of the collector theme, adorned with arpeggios blended into the nursery chime harpsichord. It gives her quiet walk down the stairs towards Freddie an aura of enchantment. That he restrained himself while untying her has shown Miranda that she is safer here than she thought, but her wary focus on a waiting Freddie suggests a sense of uncertainty. What might he might think of her attempt to escape?

“I wouldn’t be a good prisoner if I didn’t try to escape,” she tells him.

Rather than taking her straight back to the cellar, he wants to show her something and leads her into an adjacent room where his butterfly collection is displayed. Thousands of colorful butterflies, pinned and framed behind glass, cover the walls and shelves. Initially, as Miranda takes in what she sees, she is a bit stunned by the enormity of it all and scans the room in silence.

“I’m an entomologist,” he tells her, now self-satisfied that he has much to impress her with. As he details the intricacies of his collection, opening drawer after drawer of captured insects, a rhythmic harpsichord lays a monotonous pattern like the tiny tolling of a small chime to correspond to the death of each butterfly. Over this, high-end harpsichord intones a variation of the collector theme. The music is unbearably sad, the high-end harpsichord cutting through Terence Stamp’s voice like the small cries of the insects he is now displaying.

When he completes his presentation, Miranda inspects his work more closely. “They’re beautiful,” she says, “but sad. How many butterflies have you killed?”

“You can see,” he says.

She lifts a specimen pinned to his work area and views it under a magnifier, studying it intently. Here the ornamental flavorings of the score recede and the tone darkens. Her face reflected over the butterflies in a glass case, she tells him, “And now you’ve collected me, haven’t you?”

Turning to him she asks, “Is that what you love? Death?” A musical sting follows, a variation of the gloomy chord we heard over the opening credits as the film’s title appeared. When Freddie leads her out of the room the sting becomes a subdued variation of the collector. Through this, Jarre has reinforced the psychological aspect of the story with music. Freddie is a collector, habitually, compulsively.

The correlation between collecting butterflies and beautiful girls is obvious but psychologically sound, the end result of a lifetime of one man’s idea that beauty can only be appreciated when captured and placed under glass.

Back in the cellar, music unusually underscores a conversation between the two. Miranda is sketching a self-portrait in charcoal, sparking both to talk. Freddie is enchanted that it’s a picture of her. This is backed by the main theme on flute. It’s peaceful, soothing, reflecting the quiet concentration often required to create a piece of artwork. As the conversation develops, the score fades away.

Miranda’s portrait is only a so-so likeness, but Freddie is willing to buy it for 200 pounds, (a lot of money at that time). Jarre continues to hold back because Freddie is distracted by Miranda’s offer to pick out another drawing to purchase. He had earlier agreed to get a note to her mother, which he dictated. While he looks for a picture to purchase, she slips a tiny note into the envelope to her mother. Unfortunately, he discovers the note.

The note says she’s been kidnapped by a madman, and suggests where to find her. Even the moment Freddie discovers the note is without score. Angry Freddie suggests she never tries to talk to him, and that’s why she hasn’t gotten to know him. Her friends would laugh at him, he tells her, but she disagrees.

He sees she has been reading J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, and asks if he would be able to discuss the book with her friends. “But of course you would!” she says. “Then I’ll read it,” says Freddie, and tears up the rescue note as he leaves, adding that she didn’t have his name or the location right anyway. This sets up the beginning of the third act, and also initiates the first of the longest remaining cues in the film.

As the ripped pieces of note drop, stabs of harpsichord are joined by high-end piccolo for an abrupt take on the collector theme. This is a painful comment on Miranda’s failed attempt to communicate to the outside world. There is an alarmist quality to the horns when Freddie readies a tray of breakfast for Miranda and leaves the main house kitchen. The camera moves towards the wall calendar and we see the 11th, Miranda’s last day, circled. Horns bleat out the collector theme and a chiming rhythm of harpsichord underlines the significance of this “final breakfast.”

The score remains tense since Jarre knows we are all waiting to see if Freddie will uphold his end of the bargain and let her go. When we see Miranda packing her things, dressed as she was when first brought to the cellar, the collector theme is given an ominous edge with deep organ as Freddie enters slowly with tray. Horns form the theme while harpsichord notes pluck an uneasy rhythm.

“You know today is the last day?” Miranda reminds him. When he tells her, “Yes, at twelve o’clock tonight,” the score drops off. It is effective to fade the score here, since the extension to midnight would suggest that perhaps things aren’t quite what they seem, but we don’t know for sure. A musical comment would telegraph what was to come, so Jarre avoids it.

What does happen is a discussion of the book The Catcher in the Rye, by Pierre Salinger. Freddie found it to be revolting, viewing its main character, a man Miranda describes as someone who doesn’t fit in anywhere, as a mirror image of himself. His resentment is obvious. Miranda admired the character’s truthfulness, but she now sees how different reality actually is with someone who also doesn’t fit in anywhere. The conversation ends with Freddie going into a rage about how both the Salinger book and even artwork by Picasso, things his working-class background did not prepare him to appreciate, is just plain rubbish. Freddie and Miranda’s attempts to cross over to each other’s world has only widened the gulf between them.

Oddly, in spite of Miranda’s despair over the disagreement, Jarre begins the next sequence, one of his longest unbroken cues, with music at first so light in tone that it seems out of place. Freddie rushes into the big house, and upstairs to his bedroom, where he removes a large box from his dresser. The up-tempo collector theme is bustling, joyful, with an uncharacteristic trumpet toying with the melody, the ever-present harpsichord chugging rhythm behind. Since its mood is gleeful, the upbeat tone of the score suggests Freddie, unfazed by their terrible fight, has something up his sleeve. What is in the box is key to understanding Jarre’s approach. On subsequent viewings the meaning of his odd scoring becomes apparent.

Back in the cellar, Miranda is a bit startled by his quick return with rising and briefly sustained reeds. It emphasizes her confusion. “For tonight,” he says, handing her the box and leaving abruptly. Only when notes of clarinet and flute fade when she opens the box to find a dress does Freddie’s mystery becomes clearer.

When Freddie returns that evening to see Miranda wearing the elegant dress Jarre continues the score in pleasant, sparkling tones. For her last night, Freddie has made a dinner upstairs and for this sequence, the composer not only returns to a variation we have only heard once before, but as the scene progresses, seduce us with his ultimate statement on harpsichord.

Piccolo and reeds etch out the collector theme as Miranda steps forward and holds out her hands to be tied. “Oh no, that’s all over,” says Freddie. Miranda cautiously smiles and heads outside. Jarre takes a light approach with high-end flute and harpsichord reprising the nursery rhyme variation. There is something classy about the dress, and something milder in Freddie’s manner that suggests things are about to take a pleasant turn.

In the living room of the big house, when Miranda sees the candlelit table he has set out, a dinner for two, harpsichord plays the jubilant variation of the collector theme we first heard when Freddie pranced ecstatically in the rain after first capturing Miranda. This is only the second time we’ve heard it. This rendition is also lovely, but its small simplicity, created by individual notes of harpsichord backed with low organ, suggests sadness. Like its previous incarnation, it’s a falling fragment, a simplification of the collector theme with some notes dropped to suggest clean delicacy. Its charm certainly reflects Miranda’s as she gazes at the beautiful place settings.

They toast. “We’ve come through, haven’t we?” says Miranda. The theme is deceptively cheerful, relaxed. Miranda is touched that he has framed the self-portrait she did. “It’ll be lonely here without you,” Freddie tells her, and for the first time, she seems genuinely concerned about his well-being. They sit down to what looks to be a lovely dinner. This is the first time a full conversation between them has received underscoring, and it oddly adds a touch of romance. The cheerful tone of Jarre’s music, however, has a betrayer, the harpsichord. An occasional jab of the instrument, a bit too pointed for its own good, keeps the mood unnerving. As well, the reeds wander over the melody quietly, as if waiting for an axe to fall.

When Miranda picks up her napkin it isn’t an axe that falls, but it may as well have been. It’s a ring, and Freddie asks her to marry him. The sad harpsichord fragment returns, and the descending notes now seems too perfect and controlled, just like the dinner date he has set up, all a sham to propose to her.

“You can have your own bedroom,” Freddie tells her, “You can lock it every night.” The music dies out, and in cold silence, she replies, “It’s horrible.” Yet, she realizes, if she wants to get free, she has to play along, so she says yes, she’ll marry him. It is here that she begins to comprehend the depth of his depravity, for after she has said yes, he merely rests back and darkly informs her, “Don’t you think I know you need witnesses to get married?”

Not only was the dinner a sham, but the proposal was too, for all Freddie wanted was to see was if she would say yes merely to placate him. “You can’t go back on your word!” she pleads, but Freddie states, “I can do what I like,” and muted brass call out a chilling rendition of Jarre’s theme, with high-pitched piccolo painfully suggesting the alarm of terror that must be going off in Miranda’s mind.

Miranda screams and runs to the door, but it’s locked. She darts to the butterfly collection room, searching for an escape. Continuing with the second in a series of long cues, drums pound a steady rhythm and reeds flutter feverishly until Miranda grabs a sharp tool and jabs at approaching Freddie. The distress theme takes over frantically, the drum rhythm intensifying, recalling the caged animal motif used when she first awakened. Repeated notes of piercing flute resonate as Miranda struggles to get free. The rhythm becomes a driving foundation over which the brass states a very sobering, dry rendition of the theme.

Those who are familiar with Jarre will recognize the almost galloping quality in the percussion. It is an approach he used in other scores of this period, namely in the ‘Rescue of Gasim’ sequence from LAWRENCE OF ARABIA. In that score the rhythm builds to a frenzied excitement of victory as Lawrence trots out of the desert on camel in a spectacular wide shot, having rescued a man from sure death. Here, the rhythms are savage, abstract, a cacophony playing against melody. To this raucous interlude Freddie overcomes and manages to chloroform Miranda again. The horns subside, putting an end to this wild melodic concoction with a few short toots as Miranda’s body goes limp.

Pulsing into the quiet as Freddie carries Miranda upstairs, Jarre gives us his collector theme on solo clarinet, a steady thump of deep bass and kettle drum suggesting the gradual calm overtaking what remains of their pounding fury. Slow, soothing flute and reeds replace the horn arrangement, ultimately dying away to nothing when Freddie enters his bedroom and places the unconscious Miranda on his bed. In silence he lays down beside her, putting his arm over her and slowly lifting his thumb to her breast. The glass harmonica ambience Jarre has used to indicate insanity returns as he pulls her body towards him.

Desperation has set in. Miranda awakens back in the cellar to find Freddie watching over her. He tells her he did not take advantage of her when she was unconscious, but he is still angry and accuses her of not trying to get to know him. Wailing flutes with a plunge of bassoon and harpsichord greets the situation when he leaves the cellar to allow her to think things over. Think she does, for the next sequence displays her most desperate act, and Jarre’s most beautiful.

It is sometime later, exactly when we aren’t certain, but Miranda has finished another bath, and is stepping downstairs in her bathrobe, eyes fixed on a waiting Freddie. She is filled with fear, but also resolve. The theme is low, hesitant, with soft flute and restrained clarinet casting a wary quality onto the scene. Something is up.

“Must I go straight back to the cellar?” Miranda asks, and then, “Is there something to drink?” In the living room Freddie pours her a glass of champagne and, like the nervous tension building within her, Jarre’s theme is now backed quietly by soft, churning rhythm in the reeds and harpsichord, single plucks of harpsichord carrying the melody. Miranda finishes the glass and then another. She removes his coat and sits on his lap. She requests he untie her hands, and he complies. “Am I too heavy?” she asks. “No,” he says, and so she unbuttons his shirt, softly kissing his neck and chest. Suddenly he becomes uncomfortable and gets up.

“What’s wrong?” she asks him.

“Nothing’s wrong,” he says, “it’s not right. You’re just pretending.”

She tells him to put out the light and come back to the couch. His flicking off the lamp cues the start of Jarre’s most elegant and simple rendition of his collector theme, lovingly delivered on double harpsichord. She drops her hair and her bathrobe. “Would I be doing this if I were only pretending?”

This is a seduction, for Miranda is now willing to do anything to be released. As she rests back on the couch and pulls him toward her, the theme unfolds beautifully but mechanically. The tempo is metronome perfect, unflinching. There is no embellishment here, just the melody, playing through completely, cleanly, almost starkly. Although Miranda is calling the shots here, it’s fitting that Jarre utilizes not only the instrument we have come to associate with Freddie, but the carefully delineated approach as well. Miranda is trying to use Freddie’s own weakness to her advantage.

This is the most captivating and sensuous version we have thus far heard of the collector theme, but it is curiously devoid of emotion. This is how it relates to Miranda, who in her last desperate bid for freedom is offering her body, an act only masquerading as genuine emotional involvement.

Now that Jarre’s soundtrack to THE COLLECTOR, is available on CD, it is worth noting that the quality of the listening experience of this cue is multiplied many fold by the use of headphones. The left and right hands of the harpsichord are separated cleanly onto left and right channels and a third counter melody line, added halfway through in the center, builds the piece to hypnotic proportions.

Although the cue is complete on the soundtrack release, in the film it is cut short when Freddie pulls away from Miranda in frustration and anger. He accuses her of doing what a common street woman would do to get what she wants, tosses her robe to her and demands she get dressed. As angry as he has ever been, he drags her to the front door, and as he unlocks it, she states the frightening truth: “I’m never getting out of here alive, am I?”

When the door opens, a particularly effective Wyler conceit is revealed. As quiet as it is inside, with a fire crackling in the fireplace, it’s pouring wet outside with a violent rainstorm underway. Of course, a storm that large would have been noticeable, but under Wyler’s direction, it becomes a shocking contrast to not only the quiet of the previous seduction, but a nice visual and aural metaphor of the cold truth of Miranda’s dire situation.

At this point Miranda tries the only option left. As Freddie pulls her across the yard through the drenching rain, she purposely drops her bath items when she spies a conspicuous shovel lying by the steps. When he bends down to pick up her things, she hits him over the head with the shovel. Blood pours from his head, and although she is aghast at the sight, she uses the opportunity to run. With her hands tied, however, she is still no match for even a dazed Freddie. He wrestles her to the muddy grass, as both of them get drenched in the downpour. He eventually overcomes her and drags her back to the cellar. Without score, this sequence plays all the more starkly and effectively with only the sound of their struggle and continuous rainfall.

Freddie locks her in the cellar and she makes one last attempt stop him from leaving, tripping on the floor heater and shorting it out. The door locks, and Miranda falls onto the steps, pleading, “Don’t die! Please don’t die!”

In the evening rain, Freddie has managed to drive himself to the hospital, but Miranda, alone and shivering in the cellar, hands still tied, wraps her wet body in a blanket and glances at the door. High-pitched aimless piccolo suggests the cool, clammy cellar air, with hits of kettledrum reinforcing the dour situation.

It is days later, and Freddie pulls his van into the front yard, the distress rhythm a pounding foundation through which brass and reeds weave the collector theme, upscale flute adding a sense of urgency. Beauty has left the orchestration. It is stark, perfunctory.

Inside the cellar, a weakened Miranda awakens to hear Freddie unlock the door, and the theme softens, the harpsichord fragile in its delivery. Freddie enters with a tray of food as before, and although Miranda is overjoyed to see him, she coughs and falls back. She thought she had killed him, and knew it would have been her end too, locked away with no one knowing. When she reaches for him, he pulls away. “Don’t touch me,” he tells her, “Don’t ever touch me.”

He leaves the tray and turns to leave. She tries to get up but collapses. He returns and helps her back to bed. Looking down at her and realizing how sick she is, he softens. “I still love you, Miranda.”

A pulsing harpsichord sets a clocklike tolling, suggesting what we already know, that Miranda has little time left. A bit delirious, she grabs his hands and confides, “Will you tell anyone about me?” He doesn’t know what she’s talking about. “I don’t want to die,” she explains. Here, the rhythm is emboldened by strumming guitar, all the while a tremolo flute wrenches even more melancholy from the already somber arrangement.

Miranda talks of a painting she wants to do, an image of a butter yellow field with a white, luminous sky, but she begins hacking and coughing. “I’ll get a doctor!” Freddie says and dashes outside. She hears his van drive away and sees that now she is free to escape. Yet, even though the door is open and Freddie is gone, she doesn’t have the strength to leave the bed.

The distress theme, alternating with the garden variation (used before with the unexpected neighbor), backs Freddie’s frantic drive to the doctor’s office. It’s fitting Jarre would bring back the variation used for the neighbor, for this is the only other time Freddie has considered the notion he might actually get caught. When he stares at the doctor’s office and hesitates, a three-note fragment cycled through trumpet, xylophone, flute, then clarinet creates a bit of edginess like it did when the neighbor was snooping around the house. Freddie cannot bring himself to knock on the door.

His drive back to the house continues with the distress theme. Accents of trumpet and reeds maintain a sense of alarm. He rushes down to the cellar and the distress theme merges into the collector, with the harpsichord finishing out the melody so delicately, so quietly, its quavering base line all telling us there is no question what has happened. All the life has drained from Jarre’s theme, barely making it to the last note.

Freddie says the doctor is on the way. “He gave me some pills.” He fills a glass with water, steps to bedside, and lifts Miranda’s head to give her the medicine. Her head falls back. “Miranda?” he asks. He says her name again, this time just to himself. His first reaction is to rub his hands through her hair. We hear the glass harmonica ambience one last time to remind us the insanity that started it all continues.

Terence Stamp, at a summer 2002 screening of THE COLLECTOR at the Rafael Theater in San Rafael, California, said after the production had wrapped that Wyler called and asked him, now that Miranda was dead, what would Freddie do? Stamp suggested he’d ‘shag’ her, to which Wyler was taken aback. Yet, some days later, Stamp was back in England and received a call from Wyler who said he agreed with Stamp, that that’s what Freddie would do. They had a piece of the wall from the cellar set brought to England and placed behind Stamp for a single shot of him talking about how he ‘shagged’ her dead body. Stamp said the shot was still in the film, however, the only shot of him in close up shows him covering his face with his hands, so perhaps the scene was shot as Stamp describes, but as the film now plays, the shot does not suggest anything more than remorse.

The glass harmonica ambience fades when Freddie covers his face. For a brief moment, Freddie can shut out even his own insanity, and this is a telling scene, considering what follows. He walks to the cellar door and is about to leave, but turns and sits. “I sat there all the rest of the afternoon,” he relates in voice over, “remembering. And all sorts of nice things came back.” Ultimately, he realizes that suddenly she was dead, and that dead means gone forever.

We see him drive away from his cottage, passing by a large tree in the front yard. “She’s in the box I made under the tall oak,” he informs. From the last appearance of the glass harmonic ambience until now, the film has played without score. This draws our attention to the few sounds we do hear, such as the engine of his van, which, under the circumstances, has a hollow, chilling effect.

Then we are in town, inside the parked van, seeing another girl approach, from Freddie’s POV. The jazzy stalking theme returns, with brushes dashing out the now compulsive rhythm, sharp hits of cymbal with single plucks of the unstoppable harpsichord emphasize a downbeat that cleverly reinforces the concept of mental fixation. As delivered by Jarre, the theme is even more determined than when Freddie first stalked Miranda at the beginning of the story.

This new girl is dressed like a nurse, and not as sophisticated in appearance as Miranda. Freddie’s thoughts about Miranda continue in voice over as he watches the nurse: “For days after she was dead, I kept thinking, perhaps it was my fault after all that she did what she did and lost my respect. But then I thought, no, it was her fault. She asked for everything she got.”

The compulsive nature of Jarre’s theme makes perfect sense now, as the harpsichord painfully tings its unchanging rhythm. As this new girl walks passed Freddie’s van his voice over gives us his final thoughts: “My only mistake was aiming too high. I ought to have seen I could never get what I wanted from someone like Miranda with all her la-di-da ideas and clever tricks. I ought to have got someone who would respect me more. Someone ordinary. Someone I could teach.” The nurse walks towards a narrow quiet street and Freddie pulls his van out after her as the stalking theme continues like a tightly wound metronome, click-clacking away as if it will never stop.

This gives way to the end credits and Jarre’s final rendition of his collector theme. This version is an anomaly in that it is fully orchestrated, the theme as we’ve never heard it, elegant and forthright, a full string section carrying the melody. The end credits appear over beautiful images of butterfly wings, and combined with Jarre’s full-blown rendition a sense of enchantment is created. Finally, here is the theme as envisioned by a sane mind, and its lack of restraint finally allows the audience to distance itself from Freddie’s peculiar brand of madness.

A suite from THE COLLECTOR is on a difficult to find 2015 CD release Notre Dame de Paris: The Music of Maurice Jarre. Aside from six cues from the non-film Notre Dame and some other Jarre film scores, THE COLLECTOR suite contains ‘Main Title’, ‘The Catch’ (including ‘The Stalking’ theme) and ‘End Credits’. The rendition of the Main Title is reasonably well recreated, ‘The Catch’ less so. The End Credits, the least successful, has none of the beautifully elegant orchestration used for the film. At least it’s nicely recorded.

Mainstream re-released their original soundtrack to THE COLLECTOR with no additional cues, this time paired with Mark Lawrence’s excellent score to the 1962 DAVID AND LISA, a fine film directed by Frank Perry. As of October, 2023, it is still available on Amazon in the U.S. The liner notes say this CD release was remastered using the original stereo tracks for the first time. This may have been true for a CD release, but THE COLLECTOR LP was originally released in both mono and stereo back in 1965. The stereo release had a higher sales price.

THE COLLECTOR has had a strange effect on people. It is one of those films that some people, primarily males, hold close to their hearts. It is a favorite of many, and has developed somewhat of a cult following. This is a rather disturbing notion, considering the subject matter, yet the film is so intelligently scripted, performed and scored, that the legacy it leaves behind is not so simply described.

Perhaps something Terence Stamp himself said about his experience shooting the film sheds light on the effect the story and its characters have on people. As previously mentioned, a technique actors use to elicit a performance out of their fellow actors was also used by Stamp and Wyler on THE COLLECTOR. Although he knew Ms. Eggar before the shoot, by a suggestion of Wyler’s, Stamp remained cold and unapproachable to her during production. This enhanced the tension between them on camera. Eggar gave arguably the best performance of her career, which may or may not have been helped by the aloof Stamp. Years later, according to Stamp, she forgave Wyler for her treatment, but apparently to this day, she has not forgiven him. Perhaps she saw a little of Freddie in Stamp.

Up to Jarre’s passing in 2009, aside from the suite released on

Notre Dame de Paris: The Music of Maurice Jarre, the composer didn’t much acknowledge his work on THE COLLECTOR, but in terms of sheer psychological complexity and musical invention, it ranks as not only one of his greatest works, but certainly one of the finest scores of the 1960s. One can only hope a proper re-release happens, so it can rightfully take its place alongside other greats of the era.