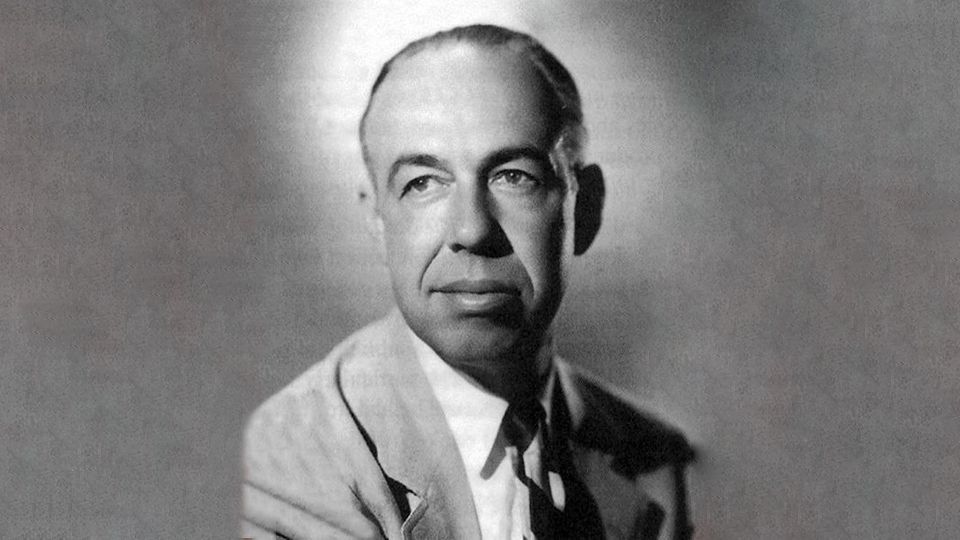

Roy Webb

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.20/No.77/2001

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven and Dirk Wickenden

How many times do we talk of Jerry Goldsmith, John Williams, James Horner, John Barry et al? A great deal, almost as often as we mention Korngold, Steiner, Newman, Rozsa and so on. But how often do we think about George Duning, Roy Webb, Frank Skinner, and Cyril J. Mockridge? These men were just as active, if not more so, than many of our favorites in the Golden Age and their contribution to the art and craft of film scoring is often overlooked. Roy Webb is definitely one of the Golden Age’s underrated composers. Only as late as the ‘nineties did he receive an overdue appreciation, having a chapter devoted to him in Christopher Palmer’s excellent book ‘The Composer in Hollywood’ and a compilation CD from Silva Screen’s Cloud Nine Records label, entitled THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE.

Born in New York on the 3rd of October 1888, Webb was exposed to the Metropolitan Opera by his mother and the works of Gilbert and Sullivan by an uncle. Also a painter (of the artist variety, not an interior decorator!), Webb eventually worked on Broadway shows prior to going to Hollywood in 1929 to orchestrate RKO’s RIO RITA for Max Steiner. He returned in 1933 as Steiner’s assistant and remained at RKO for most of his career, where he became their next major music director after Max Steiner, the association only ending when RKO was sold to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz’s Desilu television studios in 1955.

Whilst the invention of the click track for precise timings can be pretty much attributed to the premier animation composers Scott Bradley and Carl Stalling, Webb and Steiner were both pioneers of its use in live action feature films. (Many of Webb’s film scores at RKO were co-conducted by Constantin Bakaleinikoff, another of the studio’s music directors). His work in one capacity or another at RKO figured at over three hundred films across almost a Quarter of a century.

Roy Webb’s first credited film score as composer was ALICE ADAMS in 1935, but his most famous score is for the Alfred Hitchcock film NOTORIOUS (1946) and his other credits include the 1941 musical LET’S MAKE MUSIC, comedies such as 1938’s BRINGING UP BABY; spectacles like 1935’s THE LAST DAYS OF POMPEII and 1947’s SINBAD THE SAILOR. Webb was particularly adept at scoring films noir, which included the 1944 thriller MURDER, MY SWEET (aka FAREWELL MY LOVELY) and 1945’s THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE but is also admired, as evidenced by the title of Cloud Nine’s compilation, for his scores for the films of Val Lewton, including CAT PEOPLE from 1942 and its sequel two years later, CURSE… and 1943’s THE SEVENTH VICTIM and THE LEOPARD MAN. Indeed, for the year 2000, the Marco Polo label has revisited the Lewton/Webb films with their newly recorded compilation album CAT PEOPLE. Another notable film in Webb’s oeuvre is the KING KONG inspired MIGHTY JOE YOUNG from 1949, which featured a Steiner-like score in the best tradition and he provided additional music for 1944’s THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, a fact the irascible Herrmann, the principal composer, did not forget. In fact, Webb worked in practically every genre.

Fixed Bayonets! This 1951 Twentieth Century Fox film directed by Samuel Fuller is set in its year of production, during the war in Korea. Therefore, it can perhaps be considered a form of propaganda. The basic storyline tells of a soldier, Corporal Denno, who despite rising through the ranks finds himself unable to give orders (although he can take them) and unable to fire upon the enemy. During the course of the squad’s holding off the enemy from a cave, he eventually assumes command by default, when one by one his superior officers are killed and, after hesitating almost too long, succeeds in shooting his first man. He then leads the remainder of the outfit to the rest of the platoon. The leading actors included a pre- VOYAGE TO THE BOTTOM Of THE SEA Richard Basehart as Denno, Gene Evans (DONOVAN’S BRAIN) and Michael O’Shea (THE BIG WHEEL) as Sergeants Rock and Lonergan respectively, with James Dean in a bit part as one of the soldiers.

The film commences with a military pomp-and-circumstance theme over a credit of the filmmakers thanking the US Army for their co-operation, then the first visuals of a jeep carrying a general through snow covered terrain is treated tacitly by the composer. Webb enters again after a brief dialogue at base camp, which precedes the opening credits. Over the titles, Webb scores a military march on brass and snare drums, which fades out after the director’s credit, as if it were a marching band walking past the listener/viewer (the “Doppler” effect). Webb spots the movie very sparsely with transitional cues and brief uses of “Taps” and related fanfares, when I believe the film really required more music, perhaps adopting a gung-ho type of approach to bolster the propaganda feel or a more dramatic approach (the “war is hell” type of score).

An early scene shows the majority of the platoon marching off, whilst leaving a rear guard to outwit the enemy. A male choir sings on the soundtrack, whilst Webb ingeniously layers an eerie, distorted string and organ effect over the top (the sort of sound one might hear in a horror film of the period), playing from the point of view of the soldiers left behind and their anxiety. A similar effect is obtained with “Taps” performed softly on the brass, with the distorted effect as the camera tracks across the soldiers asleep in the cave.

There are a number of voice-overs, which are the men’s thoughts and Webb lays down music underneath, something he was particularly adept at in films. There is also source music, of a sort, as the Chinese play their indigenous bugles from all directions to confuse and play psychological games with the Americans. One of the soldiers says, “They’re playing our Taps”, to which someone else replies that it’s just the last three notes that are the same (sounds like he’s been listening to too many movie scores!).

Two of the men are dispatched to capture a Chinese bugle, so that the Americans may play the enemy at their own game, performing the oriental Taps-like calls to confuse them in turn.

The film, which admittedly is somewhat of a low budget pot-boiler, is a tad plodding in its structure, when more music may have helped the drama and rare suspense (for example Basehart’s unscored tiptoe through a minefield one of his fellow soldiers set out). A soundtrack album would be unworkable, but the score is worth noting for Webb’s weaving of the military tunes and his distorted sounds.

Marty Fine Film. As a freelance composer following the dissolution of RKO, Roy Webb was lucky enough to become attached to a modestly budgeted $343,000 production, a “sleeper” which would emerge as a multi-award winning film and one of the best dramas of the fifties. United Artists’ sensitive 1955 film MARTY starred Ernest Borgnine as the title character and featured a script by the talented Paddy Chayevsky. Chayevsky, like such writers as Rod Serling and Gore Vidal, directors Delbert Mann and Franklin J. Schaffner, actors Charlton Heston and Paul Newman and composers such as Jerry Goldsmith would find artistic success in television’s STUDIO ONE, PLAYHOUSE 90 and other live dramatic presentations. An earlier production of MARTY had originally been broadcast on television as part of PHILCO TELEVISION PLAYHOUSE on 24th May 1953, with Rod Steiger in the lead role and it was a more realistic version than the later film. That said, it is today easier to be able to see the film than the television show but there is no denying the inherent quality in Chayefsky’s writing and the direction of Delbert Mann, whose services were both retained from the TV original. Mann was the first television director to go to Hollywood. He went on to direct such fare as 1958’s SEPARATE TABLES, 1967’s A GATHERING Of EAGLES and 1981’s NIGHT CROSSING, although he continued to direct television movies. Chayevsky is perhaps best known to modern audiences as the writer of 1980’s ALTERED STATES but amongst his other feature credits are 1964’s THE AMERICANIZATION OF EMILY and PAINT YOUR WAGON five years later.

Set in Webb’s home of New York, the story concerns a thirty four year old bachelor butcher (Borgnine) and the twenty nine year old spinster schoolteacher he meets during the course of the narrative. With all his siblings married, he is constantly pushed by his Italian mother and others to find a girl and get married. This is a gentle film which would not do any business if made today.

The Score. The main theme of MARTY was not composed by Webb but by songwriter Harry Warren and additional music is credited to George Bassman, who was at one time an MGM staff arranger-orchestrator. Webb utilises Warren’s melody throughout the film, with the “pay-off” coming in the end credits, when the tune is heard with its lyrics. The opening credits, over a shot of the Bronx, commences with a brass fanfare, giving way to a jaunty waltz version of the theme, highlighting strings and woodwinds. Our introduction to Marty happens when he is working in the butcher shop and, whilst serving two of the women customers, is subjected to them asking about his brother’s recent wedding and that he should get married himself. “You should be ashamed of yourself”, they both say. As he rings up a sale on the till, he looks very fed up. The film cuts to his local bar, where he grabs a beer and sits with his friend Angie and they embark on a humorous scene as they try to decide what to do for their Saturday night. Angie wants Marty to phone up a couple of girls they met at a cinema a while ago, but he does not want to.

Later in the narrative, Marty’s cousin Tommy and his wife Virginia are at Marty and his mother Theresa’s house, asking if Theresa’s sister Catherine can stay there, as she is driving Tom and Virginia to distraction. Both Marty and Theresa say it’s all right and the couple leave. The first cue of the score proper starts as Marty sits twiddling his thumbs upon their exit, on soft strings, then his theme enters tentatively on flute and clarinet. Combined with the actor’s expression, the music reveals his unspoken thought that seeing his cousin is a sad reminder of his being without a girl. An oboe continues the gentle version of his theme as he decides to telephone Mary, the girl Angie was talking about earlier. The music tails out as he dials the number; Marty asks her out on a double date but things do not go as well as he would have hoped. Although we do not hear her responses, actor Borgnine’s performance says it all – his voice is higher-pitched than normal as he talks to her and then he closes his eyes and the camera tracks toward his face as she gives him a brush off. As he goes to put the receiver back on the hook, the music enters on double basses and strings enter on the crossfade to Theresa serving dinner. The Marty theme is recapitulated on woodwind and strings tail out as Marty eats. Theresa tells him he should go out that night to the Stardust Ballroom. The conversation leads to Marty becoming upset, saying he will remain a bachelor and that he is a “fat, ugly man+ and all he gets from going to the Stardust, a place he has been to before, is “heartache”. Borgnine’s performance in the scene is powerful and is an early indication that he will earn that golden statuette at the Academy Awards.

At the Stardust, where a dance band is playing contemporary tunes, Marty meets Clara, a rather plain-looking schoolteacher who has been upset by her date dumping her (he had actually been going round offering guys, including Marty, five dollars to take her off his hands). Marty, who had berated the man that one cannot treat a girl that way, asks her to dance and she cries into his shoulder. The film crossfades to them dancing and the band plays the Marty theme, thus score moving into source subtly and effectively. As the pair leave the Stardust, Marty observes that he is talking like never before – people talk to him about their troubles but he could never find much to say to girls until now. We later see the two in a cafe, getting along like a house on fire, laughing and enjoying themselves. Then the film crossfades to later and Marty talks about his loneliness to Clara. In these intimate scenes, Borgnine’s acting is so natural that one believes in him totally. There is no underscore and no need for one – the performance carries the scene. Webb enters with a gentle love theme for woodwinds after Clara’s complimentary dialogue and her suggestion that he buys the butcher shop his boss had offered him. The cue becomes louder on trumpets on the crossfade to their walking through town to his house so he can get some money and Marty’s theme on strings emerges in the midst of the cue.

A couple of scenes later, Marty and Clara walk toward his house and Marty’s theme is presented in a very attractive setting, with a cor anglais (English horn) over a string pad, tailing out as they enter the house. Marty observes that Clara appears tense and agrees to escort her home. Music enters softly and as Marty places her coat around her shoulders, he holds her, the music growing in volume when he tries to kiss her but she pulls away. He shouts and says all he wanted was a “lousy kiss”. Accompanied by the soft music, his theme drifting in and out, he sits dejectedly and she sits alongside him, saying that she didn’t kiss him as she “didn’t know how to handle the situation”. She tells him he is the kindest man she has ever met and says she’d like to see him again. As she continues, Marty closes his eyes and when he opens them again, they are watery. Again, just in this simple action, Borgnine shows the right stuff to get that Oscar, this time with Webb’s soft but powerful underscoring. With a shaky voice, he suggests they go out the following night to see a movie and he’ll phone her, to which she agrees wholeheartedly. They then kiss gently and embrace.

As they say goodnight, the film cuts from Marty walking back down the pavement to Clara climbing the stairs to her parent’s apartment and a flourish in the strings is scored, with the gentle violin, cello and harp music representing Clara’s happy state of mind, which segues to playful music for Marty as he wanders grinning like the Cheshire cat, crescendoing as he spins around and whacks the bus stop sign, then runs across the road, narrowly avoiding being run over, yelling for a taxi. To hell with waiting for a bus – he’s the happiest he’s been in a long time. The film cuts to the Sunday morning, as Marty gets ready to go to church, whistling away.

Later, his friends say he should not call Clara up as she is ‘a dog’ (a term used a number of times in the film), the film crossfades to that night and he still hasn’t phoned Clara. The music is forlorn, again weaving Marty’s theme in and out of the cue as he tells his mother he’s going to see what Angie and the boys are doing. The cue tails out on the cut to Clara watching television with her parents and she is very tearful, still waiting for Marty’s call. Crossfade to Marty hanging outside the bar with his friends; they are asking each other what they should do for the night. Marty just leans against the wall with his eyes closed and then snaps- “Am I crazy or something? I got something good here. What am I hanging around with you guys for?” and he runs into the bar. After he dials Clara’s number, he says to a sorrowful Angie “Hey, Ang – when are you gonna get married… you oughta be ashamed of yourself”. Over the course of the film, the character has learnt that he is no different to other people and in turn, his friends are no different to him – they too are around the same age and still single. The phone is answered and Marty closes the phone booth door and says “Hello, Clara?” and his theme enters on the soundtrack as the film fades to black and the joyful vocal version of the Marty theme is then presented over silent footage of the lead actors and their credits.

Whilst it won Academy Awards for director Delbert Mann, writer Paddy Chayevsky, leading actor Ernest Borgnine and the coveted Best Picture Oscar and four other nominations, MARTY was not nominated in the music category. This is understandable when one considers the nominated films of the year in the category: Max Steiner’s BATTLE CRY, Elmer Bernstein’s seminal THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM, George Duning’s PICNIC and THE ROSE TATTOO by Alex North, with LOVE IS A MANY SPLENDORED THING winning best score for Alfred Newman and also best song for Sammy Fain (music) and Paul Francis Webster (lyrics).

Webb-Master. Roy Webb’s final film score was for 1958’s TEACHER’S PET and he went on to write for television programmes such as WAGON TRAIN. He effectively retired from film composing when his house burned down in 1961, although he maintained his position as a charter member of ASCAP and SCA. His personal outlook on film scoring can be best summed up with his comment, “I think you can hurt a motion picture a great deal by making audiences conscious of the music, unless you want them to be aware of it for a particular reason”. This is very revealing and may suggest why, amongst his colleagues, he and his output is not given as much attention – by design, it was subservient to the film, much more so than for example, Erich Wolfgang Korngold.

Roy Webb passed away on the 10th December 1982 at the age of 94, in a Santa Monica, California hospital from a heart attack. Although he never achieved the fame of some of his contemporaries, he left behind a vast amount of movie music for our enjoyment.

Notes on Roy Webb’s family background and early musical training

By N. William Snedden (27 June 2023)

Royden Denslow Webb (1888-1982) was born to Juliet Seymour Bell (1863-1930), the daughter of a New York City banker, and Edward William Webb (1844-1915), a dry goods merchant who first came to New York City in 1863 working for George Bliss & Co. and as wool buyer for the William I. Peake & Co. and the James H. Dunham Co. (formerly Dunham, Buckley & Co.) [1, 2] Roy’s middle name comes from his paternal grandmother Mary Caroline Denslow (1815-1888) who married Myron Safford Webb (1810-1871), a prosperous farmer and surveyor, originally from Vermont, who had considerable influence in the town of Windsor Locks, Hartford Co., Connecticut. Both the Webbs and the Denslows were old colonial families. Webb ancestors were from England and can be traced back to circa 1645 and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, one of the earliest settlements in North America. Roy’s father William was a member of the Sons of the Revolution and the Order of the Founders and Patriots of America. His hobbies were all befitting a gentleman of refinement, affluence and prosperity: billiards, shooting, fishing and golf, which no doubt explains why Roy himself was a very keen and high ranking amateur golf player from the time of his youth, competing in and winning championships and tournaments across America. Another fervent golfer in the family was Digby Valentine Bell (1849-1917), the comic opera singer, actor and popular vaudeville entertainer, brother of Roy’s mother. [3] William E. Webb died on Nantucket island in 1915: Siasconset, Mass. was one of two Webb family homes; the other residence in Manhattan at 248W102.

Following in the footsteps of his brother Kenneth Seymour Webb (1892-1966), Roy was educated in New York at the Collegiate School and Columbia University (Class of 1910) [4]. The early years of his academic career appear to parallel that of the film composer Hugo Friedhofer, as he was gifted in drawing and painting, attending the Art Student's League before going on to university. For a time Roy was Secretary to the Fakir’s Club of America [5] and together with Kenneth ran the Sconset Actors Colony in Nantucket, Mass., one of the first summer theatres where many stars of the day received their training.

Roy learned and honed his craft composing vocal scores for numerous amateur varsity shows, vaudeville sketches and musical reviews scripted by Kenneth. One of the earliest of the musical comedies “In Newport” was given by the Columbia University Players in the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel March 8-13 1909. Thereafter the show moved on to Northampton, Mass. for a performance on March 22. Up to the time of becoming a musical director/conductor and orchestrator on Broadway in 1923 (Music Box Revue, The Wildflower, Stepping Stones), Roy scored the following productions (copyright year jointly with Kenneth S. Webb where known, otherwise performance year indicated):

The Rug Shop, a fantasy, ©1922

Steppe Around, musical comedy, ©1922

Klick-Klick, vaudeville review, ©1920

Which One?, musical play, ©1920

Such a Little Bride, sketch, ©1920

Bleaty, Bleaty; or Fifth Avenue, musical revue, ©1920

Take A Chance, musical farce, 1919

Art’s Regeneration, operetta, 1918

The Best Sellers, musical fantasy, 1918

Getting Together, incidental music, 1918

Why, Gladys!, comedy with music, ©1918

The Japanese Garden, operetta, ©1917

Love’s Attributes, Columbia varsity show, ©1915

The Mountaineer, comic opera, ©1915

On Your Way, Columbia varsity show, ©1915

Cinderella -1915, musical fantasy, ©1915

Leap Year Land, comic opera, ©1914

When Dreams Come True, additional music, 1913

The Rainbow Cocktail, operatic fantasy, ©1913

Marching Through Georgia, comic opera, ©1913

The Forbidden City; or The Bride of Brahma, comic opera, ©1913

The Peach and The Professor, musical comedy, ©1912

King Karl of Kronstadt (re-write of In Newport ©1909), musical comedy, ©1911

The Dream Girl, operetta, ©1910

Roy’s principal music teacher was the violinist Julius Vogler (1858-1941) who worked in theatre playing and directing H.C. Miner's Paragon Orchestra on 8th Ave. It is reported Vogler fiddled in the same chair for twenty-seven consecutive years (from c1885) and closed his violin case with a deep sigh of regret when the house closed in 1912. According to the American conductor and orchestrator Mayhew Lake (1879-1955): “Vogler was the greatest analytical harmonist I have ever known. Every note, chord, sequence or development in the three B’s - Bach, Beethoven, Brahms - was recorded in his John Kieran (1892-1981) photographic mind and memory.” [6] Vogler was said to be a direct descendent of the Baroque composer George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) [7] and was the author of eight books on music, e.g. How to Compose Music, 1910; Complete Course in Harmony, 1921; A Modern Method of Counterpoint, 1935. For many years he ran a studio in Steinway Hall, working as a music agent with Otto Herrmann. Vogler died in Ridgewood, Bergen, New Jersey. [8]

By 1919 Roy was in the movie business with his brother. He worked on the Realart picture The Fear Market providing the musical accompaniment in collaboration with the violinist Dorothy Hoyle, the adopted sister of Kenneth Webb and a soloist formerly travelling with John Philip Sousa’s band. [9] Thereafter Roy assisted his brother on a number of silent film productions and was usually credited under the title “Art Direction.”

Roy Webb’s Hollywood film career will be found in Christopher Palmer’s book The Composer in Hollywood (Marion Boyers, 1990). A précise biography, also written by Palmer, is available in Grove Music Online. However, details of Roy’s early training and formative years are scant in both sources. Palmer states in the above book (p162): “The main musical influence in [Roy’s] life was his mother, who frequently took him as a boy to the Metropolitan Opera; and an uncle who was a well-known Gilbert and Sullivan favourite ensured that he had a thorough grounding in comic opera as well.” Palmer does not say which uncle or give out any names but he is most likely referring to Digby Bell cited above, the older brother of Roy’s mother Juliet. A biographical portrait of Digby Bell will be found in Who's who on the Stage, 1908 edited by E. De Roy Koch and Walter Browne (B.W. Dodge & Co, 1908).

For Kenneth Webb’s biography see The First One Hundred Noted Men and Women of the Screen by Carolyn Lowrey (Moffat, Yard and Company, 1920).

References

- The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Volume XVI, James T. White & Co., New York, 1918.

- Ancestry of Myron Safford Webb , Developed by Charles D. and Edna W. Townsend; “The Log Book” of Myron Safford Webb 1840, Transcribed by George McKenzie Roberts, Aceto Bookmen Sarasota FL, 1985.

- A photograph of Digby Bell playing golf in Nantucket can be found in Wikipedia, so in all probability Roy was close to his uncle and played golf with him up to the time of Digby’s death in 1917. More importantly he would have learned a great deal from him about music and the stage. The Digby Bell Opera company was formed in 1892 and toured until around 1899. Reminiscences relating to Bell will be found in De Wolf Hopper’s biography Once a Clown, Always a Clown (Little, Brown & Co. 1927) and in Hedda Hopper’s autobiography From under my Hat (Doubleday & Co., 1952). Digby Bell starred in a couple of silent movies: The Education of Mr. Pipp (1914) and Father and the Boys (1915) so that too would have had an influence on Roy and his brother Kenneth.

- Claire R. Reis, Composers in America: Biographical Sketches of Contemporary Composers With a Record of Their Work, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1947. Kenneth S. Webb was Columbia Class of 1906.

- In Florence N. Levy, Editor, American Art Annual 1911, Volume IX, New York NY. From 1891 to 1914, students attending the Art Students League in New York held annual exhibitions of “fake” art parodying work done by their instructors and other important artists. The students called themselves The Society of American Fakirs.

- Mayhew “Mike” Lake, Great Guys: Laughs and Gripes of Fifty Years of Show-Music Business, Bovaco Press, 1983. Lake states that many of Vogler’s pupils came to the theatre for lessons. An ardent fisherman Vogler lived in the country. Lake relates an anecdote about Vogler’s music bag containing pupil’s corrected harmony lessons which he used to wrap up the fish he caught.

- Julius Vogler was related to Handel through his mother Christianna Handel (1828-1917) who was born in Saxony, Germany. Judging by U.S. decennial census records Julius’s father John Elias Vogler (1819-1879), from Mainstockheim, Germany, was also a musician.

- Death notice of Julius Vogler in Musical Courier, Jan. 5, 1942.

- Dorothy Hoyle was also as a member of the Sconset Actor Colony in Nantucket and appeared in their annual Gambol July 28 and July 29 1914. Roy’s uncle Digby Bell was another member present on that occasion.