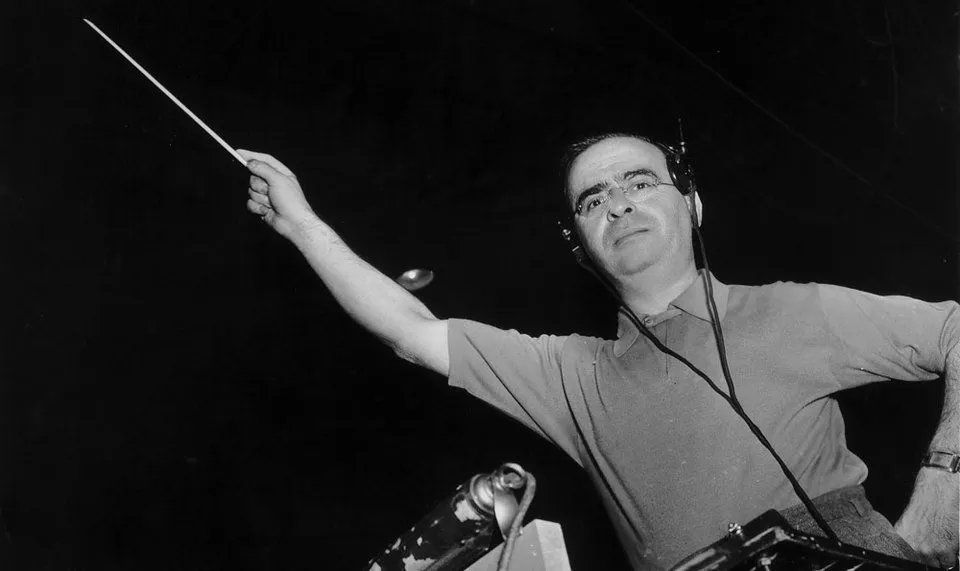

Max Steiner: Maestro of Movie Music

Interview with documentary filmmaker Diana Friedberg by Roger Hall

Originally published at Film Music Review, with permission of the editor Roger Hall

Winner of the Cannes Film Festival! Max Steiner Maestro of Movie Music feature documentary by Diana Friedberg, ACE tells the story of one man who more than any other invented the art of film scoring in Hollywood.

What made you decide to make a documentary about this major Hollywood film composer?

The original concept of making a film about the life and music of Max Steiner began when I was a student at USC in 1975 and 1976 completing a MFA in film production. Prior to this experience I had been working as an editor and even a director of feature films in South Africa. In 1970 an editor named Joe Masefield from New York was brought to Johannesburg to cut a film to which I was assigned as an assistant editor. The producers hoped he would bring a flair to the cut which could make it more marketable on the international market. What Masefield’s presence did do was introduce me to the music of Max Steiner. Being an avid fan, he insisted we begin the day’s work drawing inspiration from Steiner’s scores booming from a portable cassette player. When I was accepted into the program at USC and left South Africa in 1974, Masefield told me to contact Steiner’s widow, Lee who was still living in Beverly Hills. We soon became good friends as she showered me with kindness and hospitality. She introduced me to John Morgan who had befriended Max and had spent time with him discussing his music.

At this point I also befriended Fred Steiner, a composer and film historian who took me under his wing as I expressed my interest in doing a short documentary on Steiner. As a student I was able to solicit favors from a film company that owned a 16mm library of Warner films and each week they would deliver cans of prints of Steiner-scored films. Fred, John and I would spend weekends binging on these films. Along with this came meetings Fred would organize to meet luminaries such as Elmer Bernstein, Johnny Green, Hugo Friedhofer, David Raksin and even Eleanor Slatkin – cellist in many Steiner sessions. Max’s Star Laying ceremony in Hollywood occurred during this period and I was present with a student cameraman doing our first unofficial shoot for the documentary I was hoping to make. The first disappointment was when I was told the footage we had shot had been ruined in the lab at USC. This was soon followed by the professors telling me I could not make a documentary since the school preferred to focus on dramatic story telling. Heartbroken I shelved my project. When I left Los Angeles to return to South Africa, Lee hosted a farewell dinner in my honor for all the Steiner friends I had met during my stay in Hollywood. No celebrity could have been feted better. Her kindness and generosity of spirit has never been forgotten.

Fast forward 42 years. My husband Lionel and I, now settled in Los Angeles having left South Africa with our children in 1986, are sitting at a table preparing for an evening of outdoor entertainment at the Pasadena Pops under the baton of Michael Feinstein. We are joined by another couple. We start chatting and discover that all four of us are passionate film music buffs. I mention my long-lost project of Max Steiner and he suggests I should resurrect the idea. Everyone is dead, I say. He says “No, there are lots of people still interested in his music.” And so, film music historian Bill Rosar and his wife Leslie Anderson organize a Max Steiner Symposium through the Bob Cole Conservatory of Music, California State University Long Beach in February 2018. It was called Max Steiner: Man and Myth. Here I met all the leading players from around the world who are still involved in studying Steiner’s legacy as well as the curators of his collection at the Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. Encouraged by an enthusiastic crowd of his followers, I decide to go ahead and resurrect the documentary project and realize a dream I had never forgotten.

How did you go about finding the people to speak about Steiner?

Many of the key players were at the symposium so I was introduced to them all on one weekend. John Morgan my friend from my USC days had forged an amazing career with William Stromberg rerecording so many Steiner scores as well as other composers, jumped onboard and was thrilled to be able to finally get the film made. We both realized that it was all serendipity that the project should come alive now as it promised to have a larger canvas than that of a student project. I had heard that Michael Feinstein was a Steiner fan and getting him onboard was a challenge. His busy schedule prevented a commitment to a filming date. One day sitting at a theater I read an ad in Playbill that there would be a Broadway on the Rhine cruise featuring Michael Feinstein. The ship set sail from Vienna. Since I had never been to Vienna it seemed a great opportunity to combine a recce of locations tracing Steiner’s early life growing up in this city of music and finally meeting Michael and getting him to commit. It was only a week away, but I found a reservation and set up a location scout in Vienna. Both the time spent in Vienna researching his early life and the ship cruise was highly fruitful. I was also able to schmooze with the guests, many of whom were Broadway producers and lovers of musical theater and movies. I spoke about the film project and received my first donation from a fan from Canada. With my first check banked and Feinstein committed, I was ready to begin the filming process.

Was it difficult to find funding for this documentary and where did you go to find the funds you needed?

It is always difficult to find money for a non-profit film which is what I set up through a fiscal program run by the International Documentary Association in Los Angeles. I solicited some friends and family and raised a small amount of donations as we went along. It ended up being a very low budget film but managed to scrape enough together to finish the film. I was very much a one-man team covering research, production, direction and editing of the film – without a salary of course! The film was truly a labor of love. Everyone was excited about the project and gave generously of their time and talent without renumeration. The team at BYU under the leadership of the ex-curator of the Steiner Collection, James D’Arc worked with me every step of the way as we combed through the rich treasure trove of material that they had archived concerning Steiner’s life. It was all used to flesh out and illustrate his story. The university even generously gave permission to use the talents of their 100-piece Philharmonic Orchestra to play Steiner cues that we were able to film. Morgan and Stromberg gave their time and extraordinary expertise preparing the musical scores for these cues. They rehearsed and conducted the students who did a masterful job playing film music for the first time. And all this for a pizza lunch for the students! It really was extraordinary how everyone rallied around to help make the film happen.

Did you find much support, financial or vocal, from the film music community?

Everyone I approached to interview agreed to appear in the film. I did an initial interview session against a green screen for two days which gave me enough material to create a rough cut. The first interviews really covered an amazing amount of territory. Steven Smith who at the time was busy writing Steiner’s biography was really a key figure. With budget restrictions, I wanted to see what I had before planning a later shoot with further experts. This worked out well as it enabled me to prompt missing responses on the next round of people from the film music community. Of course, there were other greats that I would have liked to have included like Steven Spielberg and John Williams who are both great admirers of Steiner. Spielberg was busy with WEST SIDE STORY and Williams would not accept unsolicited material! So without major resources and contacts, the film stands testament to those who love and appreciate Max Steiner and were willing to participate.

One of the exciting things that came out of this project was that BYU and curators of the Max Steiner Collection went ahead and organized a second Max Steiner Symposium at the end of 2019 which would coincide with a screening at the university of the first cut of the film. Another highlight of the weekend would be a live performance by the BYU Philharmonic of the full score of King Kong played along with the film. It was wonderful to know that a whole new generation of young people had learnt about Max Steiner and were exposed to a live performance of a film music score. This was all stimulated by a renewed interest in film music generated by our project.

What do you hope viewers will take away from your 2-hour documentary about the music of Max Steiner?

It is hoped that the film will give people a new understanding of film and the complexities of film making and the important role that music plays in the total cinematic experience. From its early history during the Silent Era to the development of sound movies when the soundtrack was able to finally fully enable an audience to feel emotions through the use of music.

Thank you for answering these questions and for providing film fans with the fascinating story of this “Maestro of Movie Music.”

Max Steiner Documentary

linkThe documentary may be ordered at this link: Max Steiner Feature Documentary – Blu Ray | Diana Friedberg

See also this website link: Max Steiner | Diana Friedberg