Juan Quintero: The History of Sound in Spanish Cinema by Julio Arce

Originally published in Clásicos del Cine Español, vol. 1. Juan Quintero, Madrid, Iberoautor, 2000

Transcribed

text reproduced by kind permission of Julio Arce UCM

In one of the latest publications on Spanish cinema - written by Román Gubern, José Enrique Monterde, Julio Pérez Perucha, Esteve Riambau and Casimiro Torreiro, and entitled Historia del cine español, Madrid, Cátedra, 1995-, which aims to offer an organic and comprehensive historical vision to cover the gaps and historiographical deficiencies of our cinema, we find the absence of any reference, however small, to Spanish film composers. This oversight is not justified by the poor quality of Spanish film music, or by the carelessness of its directors; both in past eras and in recent years, we find examples of filmmakers who have shown great interest in film scoring. Without the presence of composers such as Juan Quintero, Manuel Parada, Jesús García-Leoz, Isidro B. Maiztegui, Carmelo Alonso Bernaola or José Nieto, to name but a few, any historical approach, however well done, becomes a 'dull and incomplete history of Spanish cinema'.

The contribution of Spanish film composers has not been fairly valued, neither in the world of filmmaking nor in the field of musical research; the lack of interest shown in musicians and their soundtracks is reflected in the scarcity of recordings, monographs and specific studies on their works and artistic paths. Moreover, most of the published works lack the necessary scientific rigour, so that the analysis and evaluation of the soundtrack in Spain from the perspective of musical techniques and their relationship with the image is still, one hundred years after the invention of cinema, a pending task for Spanish film and music historiography.

Film music of the 1940s

It is not too doubtful to say that the best thing about Spanish cinema in the 1940s is its music. Post-war cinema was influenced by the political situation resulting from the civil war; the possibilities for creating quality cinema were diminished by the weakness of the industry, the censorship restrictions on the exhibition of foreign films and the choice of themes and scripts, which reflected the principles and doctrinal interests of the Franco regime. However, Spanish film music of those years, immersed in cardboard historical dramas or 'white telephone' comedies that had little to do with Spanish social reality, reveals the mastery of our composers and shows a level comparable to that of France, Italy or the United States.

The inescapable separation, organization or categorization into genres, styles, trends, etc., imposed by our culture, has taken the soundtracks of the forties as paradigms of cinematographic musical creation. Musicians such as Max Steiner, Alfred Newman or Erich Wolfgang Korngold laid the foundations for the aesthetic definition of a new genre. However, it should not be forgotten that music is introduced into cinema to perform expressive and structural functions, submitting itself to the rest of the audiovisual discourse. Cinema is also an industry, so artistic creation, whether visual, literary or musical, must be analysed from new perspectives and not from the postulates of traditional art history.

When composers in the American industry were faced with the task of creating music for the screen, they consciously chose a language that was conservative and directly related to the music of the last half of the nineteenth century. Roy M. Prendergast argues that the relationships between music and image in film are similar to those which Wagner, Verdi or Puccini had to resolve in their melodramas. These musicians did not make use of the latest expressive trends but opted for solutions that had been proposed many years before by opera and the symphonic poem. Cinema, despite being a new form of artistic communication, was also an industry and music was part of the final part of film production; those musical codes that could be understood from the symphonic and operatic tradition were sought in order for the soundtrack to be effective, above and beyond its artistic quality in the context of contemporary musical creation.

Cinema in Spain sought from its beginnings a link with the national lyric tradition, fundamentally through ‘zarzuela’, but not with the intention of creating a specific film music based on the techniques and style of dramatic music. Film music was limited to the direct adaptation of lyric theatre works for the screen. Our cinematic history is replete with adaptations of zarzuelas in which the music is simply transferred from the pit to the soundtrack.

In Spain, Juan Quintero, Manuel Parada and Jesús García-Leoz were the most characteristic musicians of post-war cinema. Between the three of them, they produced most of the soundtracks, some of which are surprising for their quality and spectacular nature. The structure of national production during these years sought to emulate the achievements of the American industry and to contribute to the control and propaganda of a regime with a nationalist and reactionary ideology. But if, in terms of content, the cinema was characterised by the choice of themes filtered through the ideological sieve of Francoism -such as historical dramas-, the music adopted the international language initiated by the composers of the American industry. Spanish post-war musicians did not contribute novel or surprising solutions, nor did they create a specific language for Spanish cinema. They followed the guidelines initiated by the Hollywood masters with great skill and achieved an effective music that enriches the images and brings new meanings.

Juan Quintero: Biographical notes

In 1915 he entered the Royal Conservatory of Music in Madrid. He was taught solfège by Dolores Salvador, piano by Sofía Salgado and, when he moved on to the higher grade, by Joaquín Larregla. He studied harmony with Abelardo Bretón and composition with Amadeo Vives. He also studied violin with Julio Francés. He finished his degree in 1925 and was awarded an extraordinary prize for piano. His

Scherzo, consisting of two etchings on themes from Richard Wagner's Ring Tetralogy, was also awarded first prize in a composition competition at the conservatory in Madrid donated by the Círculo de Bellas Artes.

Initially, between the end of his studies at the conservatory and the end of the Civil War, Juan Quintero devoted himself mainly to performance; as was usual at that time, there was no strict limit on repertoire among performers, so that a pianist could give recitals of classical works and other occasions light music. He began to fill in as a violinist in the orchestras of several Madrid theatres. As a concert pianist he gave recitals in Madrid and on tours around Spain. He also accompanied the Russian violinist Miltems and the Hungarian cellist Faldhesy and was a member of the chamber group Doble Quinteto Español. The tango fever of the 1920s made Argentine tenors like Spaventa, whom Juan Quintero used to accompany in his recitals in Spain, very popular. He also accompanied Celia Gámez on one of her first visits to Spain.

In the early 1930s he composed, together with the violinist and composer Jesús Fernández Lorenzo, one of his best-known works, the pasodoble torero En er mundo, which was created for a black saxophonist called Aquilino who was then a hit in Madrid. In 1932 he composed

Morucha, another of his most popular songs. The lyrics were composed by the Aragonese tenor Juan García, whom Maestro Quintero used to accompany in his recitals. It was premiered on Sábado de Gloria in 1933 at the Rialto cinema in Madrid as the fin de fiesta after the premiere of the film EL DANUBIO AZUL. During this period he composed other songs, tangos and pasodobles such as

Desencanto, Ojitos de luto, A mi madre, Talento, Frenazo, Abisinia, etc.

When the war broke out, he had to combine his work as a piano accompanist and violinist in the orchestra of the Capitol cinema and the Alcalá theatre with his military duties. Although he was not sent to the front, he was mobilised and carried out administrative work for the Republican army in a barracks in Madrid. There he met Colonel Cárdenas, a great music lover, who helped him through difficult times and encouraged him to continue composing. In 1938 he married Paquita Martos. When the war ended, he began what we could call his mature phase, characterised firstly by his successful incursions into musical comedy and then by his involvement in the field of film music.

On 14 March 1941 the 'zarzuela cómica moderna en dos actos' entitled Yola, which was composed for Celia Gámez, premiered at the Teatro Eslava. It was her librettists, José Luis Sáenz de Heredia and Federico Vázquez Ochando, who offered the young maestro the composition of the musical numbers. Following its success - more than three thousand performances were given in Spain alone - he composed the music for another of Celia Gámez's musical comedies,

Si Fausto fuera Faustina. Years later she premiered in Valencia the musical comedy

Ayer estrené vergüenza, and a few days later - on 22 May 1946 - she premiered at the Teatro de la Zarzuela Matrimonio a plazos, a musical comedy written by Leandro Navarro and Jesús María Arozamena. All these works had common characteristics; As the critic of the Valencia newspaper Las Provincias recounted on the occasion of the premiere of

Ayer estrené vergüenza, they were shows presented with "ornate effects, striking scenery, succinct costumes, pleasantly undressed actresses, a great variety of scenes, brevity (and this is essential for the audience to be without fatigue and with their attention always awake), romanzas with heartfelt sentimentality, and a great deal of humour, dances with bandoneon, or whatever they call it, and with syncopated rhythms, according to the American recipe, and a constant coming and going of characters, of very varied costumes, of parades of nice and very pretty girls, with tiples-vedettes, and tiples cantoras; because there are vedettes, even in the orchestra we see it, not the violin concertino, nor the cello, but the 'jazz' on a separate stage to play its instruments in competition with the other noble instruments”. (A tiple is a plucked-string chordophone of the guitar family.)

Despite the success obtained with these works, Juan Quintero left behind composing for the lyric theatre and opted for the cinema, as he considered that the cinema offered new possibilities while musical comedy was a genre in decline. His beginnings in the cinema were fortuitous; Juan Quintero lived in Lope de Rueda Street in the same building as the actress Guadalupe Muñoz Sampedro, who was part of the Beatriz theatre company. It was at this lady's house that he met the actor Juan de Orduña. There, the man who would later become one of the most representative directors of post-war Spanish cinema, listened to the maestro Quintero perform on the piano a piece composed during the war years and entitled

Suite Granadina. Juan de Orduña was so impressed that he proposed to the musician to make a documentary about Granada based on his music. The work was orchestrated and the documentary, which was titled the same as the musical work, was structured on the basis of the score; the final bulería was accompanied by a dance performed by Mari Paz. From this moment on, her dedication to film music was constant.

The first score he composed expressly for the cinema was the one that accompanied the short film by Carlos Arévalo entitled YA VIENE EL CORTEJO (1939), based on the poem by Rubén Darío. It was Juan de Orduña, who recited the poem and who provided him with the work. Already in his first involvement as a film composer, he demonstrated his talent for visual description, which Méndez-Leite described as “a marvellous score that underlined the heroic symbolism of the images”. In 1940 he participated, together with the maestro Ruiz de Azagra, in the music for the film LA GITANILLA, directed by Fernando Delgado. Months later he composed alone the music for LA FLORISTA DE LA REINA, a film directed by Eusebio Fernández Ardavín and released on 9 January 1941. In the biographical sketch that Mariano Sanz de Pedre made in 1955, he mentions LA FLORISTA DE LA REINA as the first fiction film in his catalogue. It is possible that it was written before LA GITANILLA, or that the author himself did not consider his collaboration with Ruiz de Azagra to be relevant.

The film career of Quintero is linked to the director Juan de Orduña. We have already mentioned that the former Spanish silent film star used his music as the basis for the documentary SUITE GRANADINA. In his first feature film - PORQUE TE VI LLORAR (1941) - he turned to his friend for the musical episodes. Orduña's triumphs as a director went hand in hand with Quintero's recognition as a film composer. In 1946 he received the award for best composer from the Círculo de Escritores Cinematográficos for the films LA PRÓDIGA, by Rafael Gil and UN DRAMA NUEVO, by Juan de Orduña. Two years later he received an award for the music of LOCURA DE AMOR, at the Huelva Hispano-American Film Competition.

Juan Quintero made more than a hundred films from 1940 until he abandoned film composition in the mid-1960s. He worked with the most representative directors of the time, Eusebio Fernández Ardavín, Juan de Orduña, Rafael Gil, Ladislao Vajda, Luis Lucia, José Luis Sáenz de Heredia, Ramón Torrado, etc. He worked on films of different genres that required a specific musical treatment: historical narratives such as LOCURA DE AMOR, AGUSTINA DE ARAGÓN, ALBA DE AMÉRICA or PEQUEÑECES, comedies such as ELLA, ÉL Y SUS MILLONES or ELOÍSA ESTÁ DEBAJO DE UN ALMENDRO and also films with a folk setting such as CURRITO DE LA CRUZ or LA HERMANA SAN Sulpicio.

If the film music made in Spain was modelled on American composition, the organisational functioning differed considerably, as in our country there were no musical departments or a group of musicians who divided up the different functions necessary for the production of the soundtrack (composition, orchestration, direction and recording). Juan Quintero was in charge of practically the entire process, working under conditions that today, in view of the latest technical advances, could be described as artisan. He himself was in charge of the composition and orchestration, the hiring of the musicians and the direction. Unlike the American studios, where musicians were generally employed exclusively by the studios, Spanish composers worked independently for different film companies.

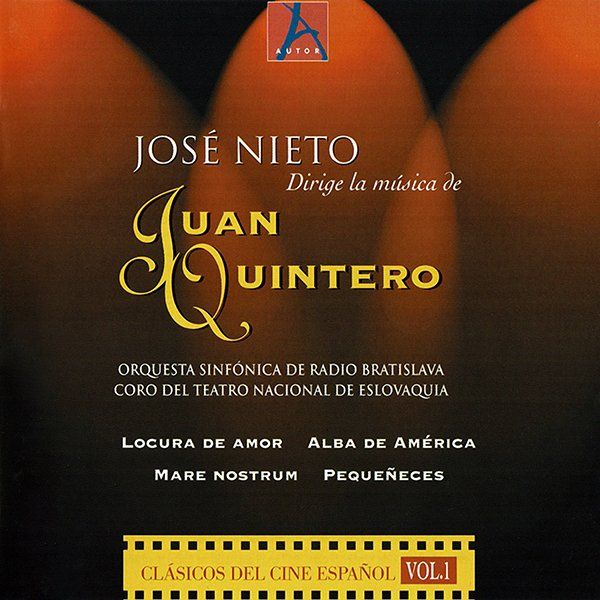

In spite of the limitations of the Spanish film industry, the results were surprising and the confirmation of this fact is perfectly reflected in the works on the disc

Clásicos del Cine Español, vol. 1. Juan Quintero (Madrid, Iberoautor, 2000) in which we can hear, in very superior technical conditions, the mastery and genius of Juan Quintero's music.

In 1952, after several years as an advisor to the Sociedad General de Autores, he was appointed Head of the Film Section after the death of José Forns. At the end of the 1950s he reduced his involvement in cinema and devoted himself to administrative work. He definitively abandoned film composition at the end of the 1960s; Cinema had moved on and the aesthetics of the post-war blockbusters were abandoned; symphonic music virtually disappeared from the screen and was replaced by the modern rhythms of pop and jazz. His health had deteriorated and deafness hindered his compositional work. Juan Quintero died in Madrid on 26 January 1980, leaving behind him more than a hundred films and the memory of a man who channelled his creativity into the difficult field of composing for the image without worrying that his audience did not know the name of the composer who had moved them.

The film music of Juan Quintero

A fact that we must take into account in Juan Quintero's work is the large percentage of music contained in the films. This issue is also the director's responsibility, as well as the selection of the sequences to be highlighted. The music is present in complete sequences and, in many cases, these are linked together and juxtaposed with musical segments that are diverse in their character and significance. In this linking process abrupt cuts occur, if required by dramatic development, or links through the union by means of a musical element. One of the transitional resources most used by Juan Quintero is the harp glissando.

Within each sequence, the music is usually articulated by means of a well-defined melody in its contours, participating in a conservative tonal language. The melodies have, mostly, a considerable extension and are structured in a traditional way in parts, giving place to repetitions and refusing motivational play. The texture is, most of the time, diaphanous, limiting contrapuntal interplay and based on the presence of a main melody underlined by chords. Let us remember that Juan Quintero was a pianist and his works were conceived on this instrument and then orchestrated, so the texture derives from the extension to the orchestra from a pianistic conception.

Each musical segment is generally identified by a sequence and is articulated through a melody that tries to capture the expressive content of the image. In the moments required by the dramatic narration, typical synchronization effects occur between the image and music that constitutes one of the defining characteristics of film music.

On a second level, we will analyse the expressive functions that music brings to the images. First, we must reflect on the use of the orchestra as a musical 'instrument' or, rather, as the expressive vehicle on which all of Juan Quintero's music - and that of most European and North American film composers during the forties and fifties - is based. In a certain sense, the symphony orchestra went directly from the theatre to the cinema in the same way that the cinema was gradually introduced into theatres. The orchestra served as a link between the tradition of the theatrical show and the new film genre. The expressive resources of the lyric theatre were used by film composers to facilitate the understanding of the new audiovisual language. But there are other reasons that we can define as symbolic: the composition for symphonic orchestra gives cinema a quality that relates it to art more than entertainment shows.

The added value that music brings to the image can be realized in different ways. One example is the identification between a character, an idea or any other dramatic-visual element and a musical sequence through a process of symbolization. We are talking about the hackneyed 'leitmotiv', so often used to define the essence of cinematographic music and reviled by those who believe that it has no sense outside the dimensions of Wagnerian drama. However, it is a fact that both Juan Quintero and most of the composers of the forties used 'themes', or, 'leitmotifs' for structural and expressive purposes. If we look at the central theme of LOCURA DE AMOR, narratively linked to the character of Queen Juana, we can see that a synaesthetic relationship is established between the musical component and the character characterization. The melody, in G minor, begins with a ninth chord; the melodic and expressive peak coincides with the dissonant note and the motive is resolved with a melodic descent with chromaticisms; to this must be added that the melody is placed in an extreme register. This melodic theme on its own does not define or bring any meaning, because it must be placed in a communicative context and it has to hold on to codes created over the years. In this way, the melody, together with the character embodied by Aurora Bautista, perfectly expresses the estrangement from reality, the boundary between sanity and madness, and the weakness and insecurity that is perfectly defined by the chromaticism.

On other occasions, the theme assigned to a character provides added value due to its identification with a historical period or culture. This is the case of the musical sequence that accompanies the death scene of Isabel la Católica in LOCURA DE AMOR, as it presents characteristic features of classical polyphony; in the same film, the Moorish princess is accompanied by a naïve melody that we immediately recognize as Arabic. The instruments also help in the identification of dramatic elements: military scenes are accompanied by trumpets and other wind instruments; a hunt will be inescapably underscored by the sound of horns.

Dramatic intensification is also achieved through synchronicity effects between music and image. Unexpected notes in fortissimo in the brass serve to focus attention on a specific dramatic episode. Juan Quintero uses the catalogue of effects that the most relevant composers have been elaborating since the beginning of sound cinema. The assignment of the music to the images is done, in short, following a comprehensible code of signs that seeks the quick identification of the viewer, in a popular cinema that wants to indoctrinate the masses more than to stir their consciences.

A good film composer is one who knows and masters the symbolic relationships between music and image. His music does not necessarily have to be innovative but effective. Juan Quintero is one of our most important film musicians, not only for the volume of his production, but also for the quality and effectiveness of his music.