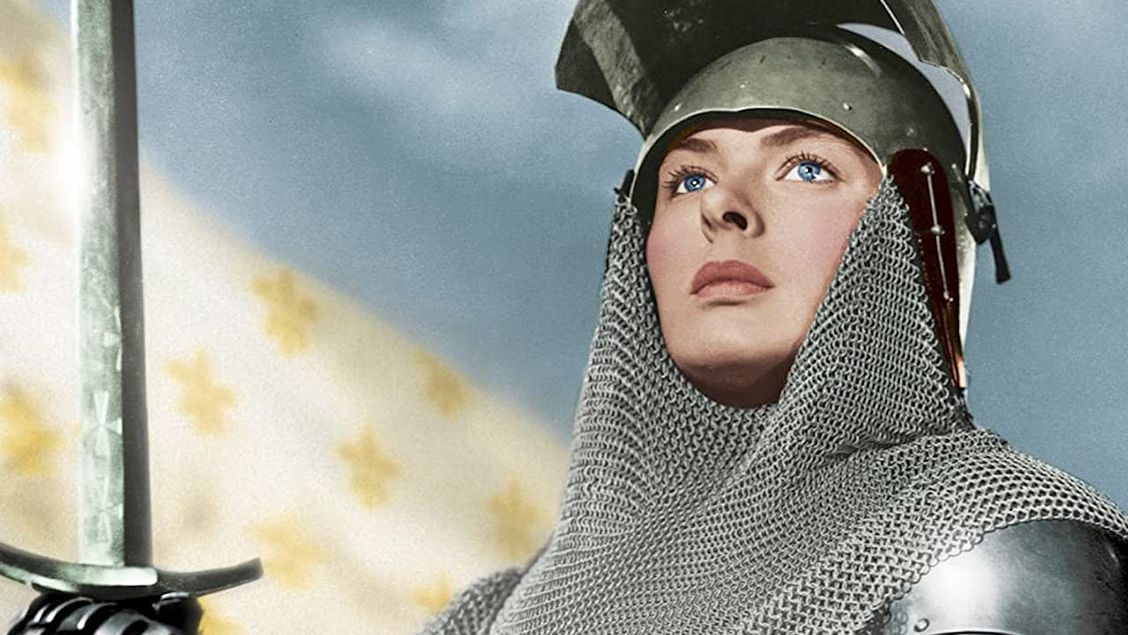

Joan of Arc

Originally published in Film Music and Altered States of Consciousness

Text reproduced by kind permission of the author Will Shaman

This film is a re-telling of the famous story of Joan of Arc, otherwise known as the ‘Maid of Orléans.’ She was a historical character, born around 1412 and dying at the stake 30 May 1431, and has been the subject of several films and a great deal of literature, both fact and fiction. This is one of two films used as case studies in this dissertation, the other being The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1999). They follow broadly the same plotline, although the 1948 film depicts the English as occupying Orléans, whereas The Messenger is more historically accurate, showing the French defending the city against the English.

Plot summary. It is 1428 and a pious peasant girl from the hamlet of Domrémy, Joan d’Arc, receives persistent visions telling her she must see Charles, the Dauphin at Chinon. He is France’s king-in-waiting, under constant pressure from the barons who lend him money, and the English and their Burgundian allies who have been attacking his country for many years, including the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 when France was ignominiously defeated. Joan is reluctant to obey her visions at first, but eventually relents and manages to persuade the local governor to allow her to make the journey to Chinon. Once there, the Dauphin’s court attempt to trick her by dressing up one of the courtiers as the Dauphin and placing him on the throne, but Joan is not fooled and she correctly seeks out the real Dauphin. To eliminate all doubt, she offers to speak to him in private and tell him things that are so secret that “they are known to you and God alone”. This she does and, believing she is fulfilling a prophecy, people flock from miles around to form a great army to rescue Orléans, which is currently occupied by the English.

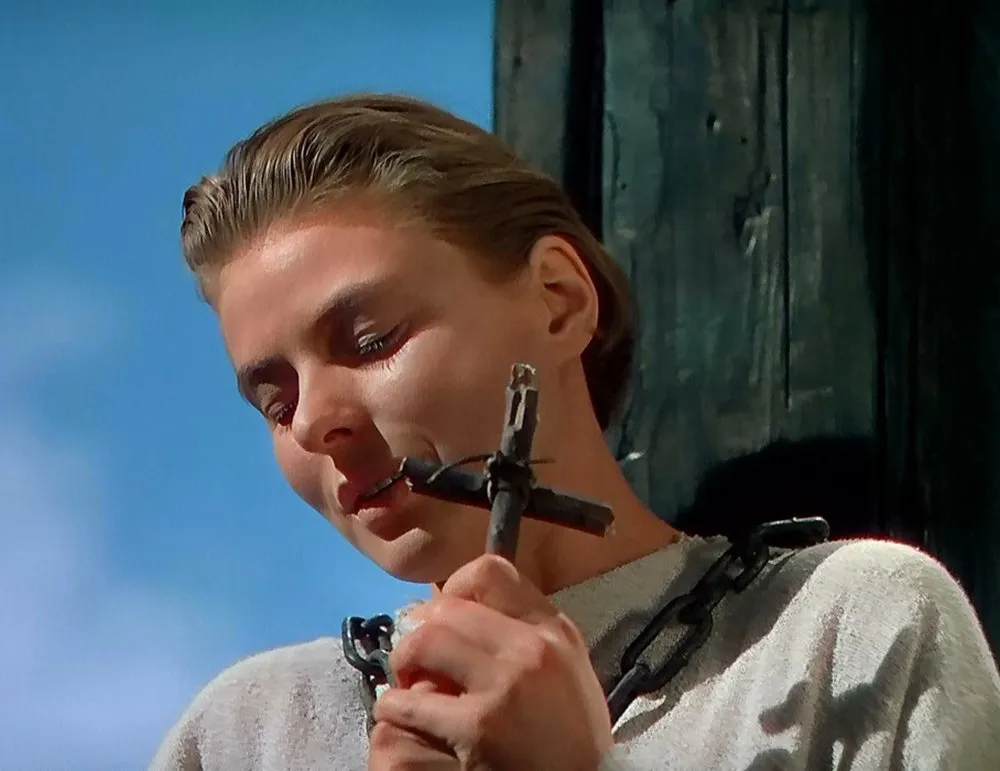

After waiting for longer than Joan wanted, they set off for Orléans and Joan meets with opposition from the French captains, although the ordinary soldiers follow her. Leading the bloody assault she is wounded and the French are repulsed. But despite her injuries, she takes to the field again and rouses the spirits of the demoralized French army who go on to take Orléans, thus opening the way for the Dauphin to be crowned Charles VII at Reims. However, the new king rejects Joan’s urgings to finish the English defeat by marching on their last stronghold at Paris, preferring instead to sign a peace treaty in exchange for Burgundian money. In Joan’s eyes, he has betrayed her and the whole of France and, to make things worse, her visions and voices have ceased. She decides to leave, despite Charles’ orders, but the Duke of Burgundy captures her and sells her to Bishop Cauchon, who is allied with the English. He then presides over Joan’s trial, at which Cauchon is seen as an unfair judge. Any of his fellow priests who contradict him are arrested and Joan is subjected to endless questioning while being kept in a terrible jail. They pressure her to sign a document denying her voices and visions, in exchange for which she will be transferred to a church prison attended by women and will escape execution. However, Cauchon goes back on his word and Joan remains in the same prison as before. She hears her voices again and they tell her to recant, resulting in her execution at the stake. This fulfills her own prophesy that she will be taken prisoner and die just over a year after first meeting the Dauphin.

Please note the version I am using is the 100-minute edit that was released in 1948 and distributed by RKO Pictures, which is 45 minutes shorter than director Victor Fleming intended. The cuts do not do the film any favours: there are several breaks in continuity that disturb the flow of the story, such as at 01:13:47, when we cut to Joan on trial and she delivers a historically accurate answer (“If I am not, may God put me there. If I am, may He keep me there”) but the question itself (“Are you in God’s grace?”) was edited out, making a poignant remark something of a non-sequiteur. It is reported that Fleming wept when he saw it. I have not been able to obtain a copy of the full-length film but, for the purposes of this research, it is in any case more appropriate to use the version that was released and watched by the majority of the public.

Analysis. It must first be stressed that Joan was filmed just after the end of the Second World War. It was a time, even in relatively prosperous America, when material concerns were paramount. There was little popular interest in pondering mystical ideas or what consciousness might be. It would not be until the late fifties, when times were less economically challenging, that alternative thinking would rise in importance (often inspired by the use of psychoactive substances, such as the so-called Beat Generation’s use of marijuana and, later, LSD [1] amongst scientists and youth culture). The sort of discourses on ASCs we enjoy today would therefore not have informed Friedhofer’s response to Joan of Arc’s experiences, and he is not likely to have viewed Joan’s story as anything other than a historical one (albeit with religious overtones). This can be discerned right from the opening credits, with its grand fanfares and large orchestral treatment signaling that this film is meant to be regarded as a great historical epic. It is interesting to compare this with the opening bars of Olivier’s 1944 production of Henry V

[2], another one of many war-related feature films to be released around the time of the Second World War. Both feature similar use of strings, brass, timpani and cymbal crashes.

Friedhofer’s approach to this film would have been pragmatic; it was after all only one of five films he scored that were released in 1948. In his lifetime, he wrote for 256 films without credit and was primary composer for another 166 movies, shorts and TV series. He was therefore an extraordinarily busy man and would have had little time to consider the sociological or spiritual implications of Joan’s story in any depth. This is characterized by his famous reply when asked about his progress with the score, “I’ve just started the barbeque!”

[3] (meaning the scene where Joan is burnt at the stake). Clearly, he treated his compositions very much as a job and worked hard to complete many scores; one might almost suggest a ‘production line’ approach. Notwithstanding this, the way Friedhofer handles his leitmotifs and themes is sensitive to the action on screen, and he creates a good sense of continuity. When asked about his approach to film composition, he is recorded as saying:

It is not important for the audience to be aware of the technique by which music affects them, but affect them it must. Film music is absorbed, you might say, through the pores. But the listener should be aware, even subliminally, of continuity, of a certain binder that winds through the film experience. A score must relate, it must integrate.

The main problem with the score from a modern perspective arises from this very pragmatism. There is a sense that the music is accompanying a drama and not augmenting the inner world of Joan. This is perhaps partly because the film has its origins as a stage play

[4] and so brings a quality of stage acting, rather than naturalism. Be that as it may, the production is deliberately stylized, with the opening narration and storybook presentation setting the tone for the whole movie. The sets and photography are presented as formal set pieces, and the overall impression is not naturalistic, which is reflected in the score.

Friedhofer’s score is exclusively orchestral, reinforced at certain points with a choir, harp and bells, and is broadly in the romantic genre that was favoured for feature films of the period. There is nearly a complete separation between the musical score and the rest of the sound track, with almost no merging of Foley and music, as seen in other case studies here. The exceptions are the battle scenes, where the horns we see blown on the battlefield merge with the orchestra’s brass section, and the coronation of the Dauphin. In this second case, we hear complex choral arrangements and plainsong; although we do not actually see the singers, we assume they must be there. The coronation scene also features a trumpet fanfare that is augmented by other, extra-diegetic, instruments, so again the diegetic boundaries are blurred. However, these examples are the exception rather than the rule. As a classically trained musician, it was natural for Friedhofer to score in this way. Of course, in a pre-digital age it was also much more difficult even to imagine such fluid interchange between the soundtrack’s various layers as we see today, so Friedhofer’s role was strictly musical. Not surprisingly, as someone of European descent who had spent many of his early years in film orchestrating for Max Steiner

[5], he employed leitmotifs, and these are all demonstrated in the overture that accompanies the opening credits [6].

There are clear musical signs for the audience to read when watching the film: lush string arrangements accompany quiet but emotionally charged scenes; heavy brass and percussion are brought out for battle sequences; and spiritual moments are given extra lift with the use of choirs. The movement from one emotional position to another is signaled using these basic musical building blocks. So, for instance, when Joan is in prison feeling despair, having denied her ASCs in order to save herself from execution, we hear a sad orchestral air [7]. She is regretting he denial, yet she is fearful of facing death. As she prays to her God, the choral leitmotif is introduced, which Joan responds to by looking up; we know from its previous use in the film that this leitmotif signals the return of Joan’s voices. As she realizes with relief her God is hearing her prayer, the orchestral component of the track is boosted with brass and this symbolizes the strength she receives from her experience. As the choir fades, the concluding orchestral chord moves from minor to major, giving a satisfying sense of completion to the end of this scene and indicating the resolution of her quandary: she would rather die than lose her soul.

The occasional appearance of Joan’s spiritual guides is signaled elsewhere, as with the scene where Joan approaches Orléans before the siege and announces the decision to strike [8]. This sequence, which could be read as a depiction of one of Joan’s ASCs, begins with an ominous theme combining heavy cello and double bass, plus horns, timpani and rolling snare drums, as the camera pans across the gathered French troops. Joan’s eyes are open at this point, so we can assume she is in a state of normal consciousness. There is an air of expectation and everyone is waiting for Joan to give her orders. The tension mounts as we are then shown the English at the battlements of Orléans, but when the camera cuts back to Joan, she has her eyes closed as if in prayer and the theme gives way to Joan’s choral leitmotif with accompanying bells, showing us she is experiencing one of her ASCs; her lips are moving silently and she looks upwards as the voices also ascend in pitch. The choir climaxes as Joan draws her sword, having apparently been told what she must do, and she gives the order to attack. The orchestra and timpani return, underlining Joan’s return to normal consciousness.

Friedhofer’s score, though excellent, makes little attempt to step outside of the expectations of the studio system he worked for. His use of orchestral and choral music is very conventional, and would not have challenged an audience in 1948. On the contrary, his music served to portray Joan of Arc’s spontaneous spiritual experiences as acceptable religious experiences [9]. In real life, her ASCs must have carried enormous force in order to drive her from her peasant home and face the potential threat of being imprisoned or killed as a heretic. The fact that the Dauphin was convinced by her experiences and was, as her ASCs predicted, later crowned king was further evidence of the ASCs’ potent influence. By flouting the conventions of the day (claiming direct communication with God; requesting leadership in the French army, despite her gender and low social standing; and, crucially, wearing male attire) Joan was highly revolutionary. Yet the musical portrayal of the ASCs that drove her references traditional church music and places Joan firmly within the acceptable domain of state-approved religion. In this regard, the score relies on a posteriori knowledge of Joan’s canonization nearly 500 years after the Church burnt her at the stake and does not attempt to reflect the fact that her claims at the time must have been highly controversial. This can be viewed as part of a larger picture, where the audience of the 1940s was politically docile and largely conformist. The notion that individual, personal experience may conflict with our culture’s dominant ideology has been sanitized in this film, leaving the audience feeling secure under the state’s (and its religion’s) protection. Friedhofer’s score, by using safe, conventional techniques and instrumentation, serves only to underline the non-threatening nature of Joan’s ASCs. I will compare this with the other Joan of Arc case study,

The Messenger where ASCs are portrayed in a more naturalistic fashion.

Notes

[1] LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) was actually synthesized by Albert Hofmann as early as 1938. However, he did not discover its psychedelic properties for another five years and it was not produced commercially until 1947. Even then, it remained largely unknown outside of the laboratory until the 1950s, when the CIA decided to experiment with it as a form of chemical warfare as part of their infamous Project MKULTRA. This included secretly giving doses of LSD to US and Canadian citizens and military personnel. Later, in the early 60s, there were scientific trials (unconnected with the CIA) involving volunteers, many of whom were students. This activity spread knowledge of LSD amongst the American population and fuelled the social revolutions that began during that decade including, ironically, peace protests that helped end the Vietnam War.

[2]

See Henry V extract.mov (duration 00:00:20). Taken from Henry V (1944), music by William Walton; directed by and starring Laurence Olivier.

[3]

From a conversation with composer David Raksin, recorded on website ‘HUGO FRIEDHOFER – Fathers of Film Music, Part 9’, MOVIE MUSIC UK

[4]

Joan of Lorraine was a successful Broadway play from 1946 by Maxwell Anderson who, with Andrew Solt, adapted it for this film. Ingrid Bergman also starred in the theatre performance.

[5]

Max Steiner, dubbed the ‘father of film music’, wrote the groundbreaking score for King Kong (1933) amongst many others. He trained in Vienna and was privately tutored by Gustav Mahler and Robert Fuchs, and his godfather was Richard Strauss, so it is not surprising that, when he went to America and started working in Hollywood, he brought with him strong influences from the European classical tradition. He is quoted as saying, “Every character should have a leitmotif”. This approach to film scoring had a lasting effect on other composers, including Friedhofer.

[6]

See Joan of Arc extract 1.mov (duration 00:04:22).

[7] See Joan of Arc extract 2.mov (duration 00:01:54).

[8] See Joan of Arc extract 3.mov (duration 00:01:16).

[9] In theology, the terms “spiritual experience” and “religious experience” are often used interchangeably, which in my opinion is a mistake. Here, I use ‘spiritual experience’ to denote one that arises from the depths (or heights) of consciousness, such that it appears to originate from a place outside of the individual experiencing it, without there being a need for it to have a relationship with any religious or cultural ideology. Such experiences have much in common with (or are indistinguishable from) other ASCs, such as certain aspects of schizophrenia, or the effects of some psychoactive substances, and are as such of potential danger to the dominant ideology. ‘Religious experience’ I use to describe one that may have originally been spiritual in nature, but has since been organized, structured and tamed, in order to harmonize with the tenets of a particular religious ideology. This makes the experience less visceral, more socially acceptable and eliminates any threat to the dominant culture. It is thus isolated from accusations of ‘Otherness’.