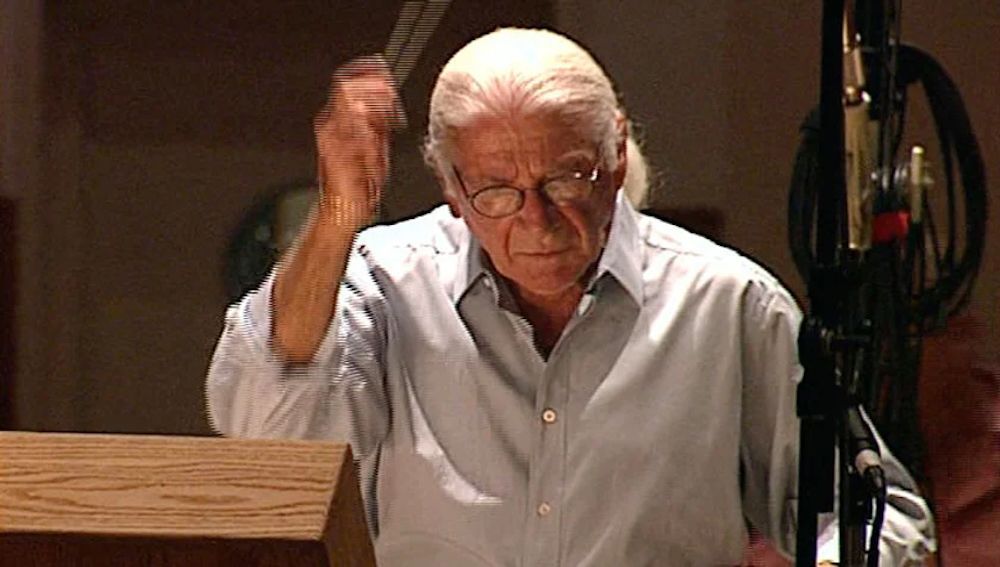

Fred Karlin on Film Music Masters

An Interview with Fred Karlin by David Hirsch

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.15/No.58/1996

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

Fred Karlin is a man who wears many hats. As a film and TV composer, he has created some wonderful scores for films like THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF MISS JANE PITMAN, WESTWORLD and the TV series THE MAN FROM ATLANTIS. Recently, Karlin has embarked on a career as an educator. However, instead of sharing his knowledge with a privileged few at some university, he chose to reach out to the public at large, first with two books, now with the launch of an unprecedented video and book series.

How did you conceive of this project?

Well, in the spring of 1994, I was having lunch with Ron Tilford, a friend of mine and a passionate film music aficionado. Jointly, we both wished that we were doing something with media, with film basically, about film music. Loving the material, in my case having just finished my second book the year before, I wanted to work with the music, instead of just talking about it. That was my urge, to get the material out there and available. Ron shared that vision and we decided to form a company together, right then, called Karlin/Tilford Productions. We decided that we would start with some profiles of outstanding film music composers and met with Jerry (Goldsmith) not that long after, sometime at the end of July. With his approval, which we wanted, we started. Within a couple of weeks after that, at the end of August, we were on the scoring stage taping THE RIVER WILD.

Jerry was your first choice?

Yes.

Why did you choose video as opposed to CD-ROM, which is a format that’s becoming more and more popular?

Video is more practical and it can be broadcast. We showed the film at the Santa Barbara Film Festival in March and we’ve been invited to bring it in October to the Flanders International Film Festival, which is one of the few festivals that majors in film music. They only give two awards, one is for “Best Picture” and the other is for “Best Use of Music in a Picture”. It’s held in Ghent, Belgium.

Right in Soundtrack!’s backyard. So after you taped THE RIVER WILD scoring session, what was your next move?

Over the next period of many months I did all the interviews, the shooting and editing. After I had edited the film, showed it around and done some fine editing, I met with Rusty Nields and Rusty came in as an editor and together we polished and finished the film.

In addition to your own footage, you augmented a lot of archival footage. How did you go about obtaining it?

I had to license it all.

Were you aware of this footage at the start?

No. It was always a question of discovery and I got help along the way. Jerry had some reference copies of some of the material including, for instance, the footage taken when he got his honorary Doctorate at Berklee College of Music. I was able to contact the college and license the footage. Other people, like Gary Kester in England, asked some of his friends and colleagues, Jonathan Axworthy, Barry Spence and Lyn Williams, all helped to get audio tapes together that would be reference material.

Did Jerry supervise the project, select what was seen?

No, not in the slightest. In addition to THE RIVER WILD scoring footage, I spent four hours one morning taping his interview and some other footage. His wife, Carol, was very helpful in offering stills, and, through Lois (Carruth), Jerry answered some faxes about factual details and approved the use of a few of his sketches. He never worked directly with us, but he was always very helpful when I needed information about materials, something about early radio days, or whatever. Then Ron and I ran it for him before Rusty and I did our final cut and polish. That version ran about 85 minutes. Jerry liked it a lot and he had a few comments which we took very seriously when we did our final edit. Not too many comments, but we had a high regard for them. He called me to tell us how pleased he was with the final version.

On some of the film clip sequences, I noticed the music was nicely mixed up louder than the dialogue.

I remixed a lot of the sequences, particularly THE RIVER WILD, because in some cases you would not have been able to hear the music from the original dub. This was designed to help the listener hear the music.

In addition to the video, we have the book. Was this part of your original plan?

We always felt that this should be a package, which included the black and white photos.

Was there ever a music CD, or cassette, considered?

There was. In fact, I spoke to all the right people, but that became impractical. There was too much to do all at once and the project as is was very expensive to produce. That’s why it’s so expensive, and we will not break even when we sell our 2,000 units. A CD would have been nice, but it was impractical.

Since you’ve planned an entire series, will each package then remain consistent, same presentation, a book, video and photos? Or will you try and make each unique?

Both, actually. The point of view is being specifically designed for each composer. I’m now producing the next one on Elmer Bernstein and the film is being tailored to Elmer, so it will be different, even though the elements will be the same in terms of the presentation. I certainly want to play excerpts from his films and find archival footage. The packaging, the book, photos will remain similar.

The video will again be framed around a scoring session?

Yes. I’ve already done one and may do another, though they may not be used the same way.

You avoided the use of a host or narrator on the Goldsmith video, will you use the same technique on Elmer’s?

Yes. I prefer that people tell their own stories.

That’s a challenge if the subjects can’t express themselves.

Well, yes. Sometimes you can be missing something and there’s no way to get it.

Elmer’s career unfolded quite differently from Jerry’s. He’s actually had to reinvent himself several times over the years. For a composer of his caliber, that’s been quite unusual. Goldsmith cruises easily from scoring science fiction to suspense to comedy. He doesn’t have to prove he can write for a picture outside in a particular genre. Elmer, on the other hand, got terribly pigeon holed as a comedy composer in the early 1980s after ANIMAL HOUSE and AIRPLANE! He eventually had to drop out of Hollywood and start over from scratch with small dramas like MY LEFT FOOT.

We talk about that. The viewer, who is a film music fan, will have his expectations satisfied. Those elements he’d want to see will be there.

Several people I’ve showed the Goldsmith video to, who were all film music fans, commented that this was an excellent educational tool. They enjoyed learning how the composer thinks. When you first set about doing this, were you targeting a general audience of film music fans or the film music student?

My approach is to satisfy both groups and a good example of that was my book, ‘Listening to the Movies’, which is written for a general audience, but all the aficionados seem to enjoy enormously. The video is also designed for both and it seems to work very, very well that way. A good example is (Silva Screen record producer) Ford Thaxton, who told me he enjoyed it enormously. He happened to watch it the first time with his girlfriend, who is not into film music whatsoever, but has a good diversity of musical tastes, rock-n-roll and this and that. She was fascinated. Gary Kester’s father is also not a film music fan, but he’s around it and was likewise fascinated.

Now, forgive me; I’m not familiar with your first book, ‘On the Track’. I’ve never read or even seen a copy, but was that written with the general public as your target audience, too?

Yes, with the one distinction that Ray Wright* and I set out very deliberately to create a textbook for composers. However, it was always my goal with that book that it be so accessible that maybe 80 or 90% would be easy to get if you came from the outside and weren’t a musician. I’m told that it does read that way and it’s just that the non-composer would never think to pick up that book. That was one of the motivations for me in writing ‘Listening to the Movies’. I was asked to do it by the publisher, but I was uncertain whether I should or not. Eventually I decided that the people who would get a lot out of the historical material in ‘On the Track’ would never see it.

You’ve been a highly respected and successful composer for years, what motivated you to try and become a teacher? Not many composers seem concerned with reaching out to the general public.

I don’t know. I think I’m drawn to communicate these things. I find myself wanting to understand them and express them to other people. When you’re doing that, you’re teaching. So, it happened through my personal inclinations. I started a book before ‘On the Track’, just because I was inclined to write about film music. I’d done two or three chapters and just put it aside. Within a year after that, Ray called and said he’d been asked to do this textbook by Schirmer and he would only do it if I’d work with him. Since I’d already started, I was inclined to do it. In 1988, Lyn Benjamin, then working at ASCAP, asked me to create a film scoring program for them.

ASCAP and I are now preparing for the 9th ASCAP / Fred Karlin Film Scoring Workshop! I lecture and teach, now and then, around the world. I’ll be teaching at California State University, Long Beach, for a week in July, and in Denmark at the European Film College for a week in August. The film music documentaries are a natural extension of all this related educational activity.

You’ve started to create what may become the ultimate film composer portrait collection. How far do you see this going?

I don’t know. A lot of it depends on what kind of support we get. The first marketing tier is the “Limited Collector Edition” and if it’s successful, then we can go further. We’re going to take it as far as we possibly can.

There’s been a lot of film music programs on television recently, the Randy Newman hosted special for the ‘American Movie Classics’ cable network, the Bravo cable network running of the Bernard Herrmann, Georges Delerue and Toru Takemitsu documentaries. Do you foresee these videos leading to its own television series?

Oh, I would hope, but that would be our second tier of marketing. As we move along on the Elmer book and video set, I am beginning to market the Goldsmith video.

What’s your average production time for each set?

About a year and a half on Jerry. I did a couple of days of shooting Elmer and some preliminary research during the time we were doing Jerry, so I’ve no idea how long it will really take. I would like to have Elmer available this fall.

Market a new title each year?

Yes. And we have a lot of other plans. We can’t contain all our ideas. Ron is great that way, he has this energetic vision. He sees all the possibilities and he relishes them. He’s got this completely relaxed comfort zone to trust me to do what needs to be done.

Are you wholesaling these sets to catalog outfits?

No, we can’t because of the production cost. Stores like Intrada have a few on hand for those who ask, SLC is distributing in Japan and some PAL video copies are being distributed by Soundtrack! But we’re doing just about everything through direct shipping for both NTSC and PAL videos.

Are both video formats part of the 2,000 total limited run?

Yes. We’ll run off a quantity in either format based on the incoming orders.

That’ll help to keep you getting stuck with copies of one particular format.

It’s working out fine and going smoothly. The word of mouth is terrific, as are the reviews – not only the film music journals such as Soundtrack! but magazines like Cineaste as well.

I know friends in the business in L.A. who have shown the video to others, so I know the industry has found it fascinating.

The response has been very gratifying.

What are your plans for the future besides this?

It’s really hard to say because I haven’t scored a film in about four years. I spent time writing ‘Listening to Movies’ and now this. My first jazz album came out on Varèse Sarabande last year, ‘Jazz Goes to Hollywood’, and we recorded a second one last March.

What about your CD anthology series?

Bob Feigenblatt produced that out of Miami and he has a whole string planned. I don’t know when he’ll do the next one. A lot of work goes into them.

It’s expensive to produce these CDs.

Yes.

Maybe one day you’ll do a ‘Film Music Masters’ set on yourself.

(laughs) I think I have a full slate to go through before I get to that!

The documentary ‘Film Music Masters: Jerry Goldsmith’ was planned to be the first in a film music documentary series but unfortunately for film music fans no follow-ups materialized. In the intervening years, Goldsmith passed away in 2004 from cancer, as did Fred Karlin. Music from the Movies released a limited DVD (1500 copies) in June 2005. Bonus features included extended interviews and 60 minutes of scoring session footage of Mr. Goldsmith working on THE RIVER WILD.

* The Rayburn Wright (1922-1990) Collection will be found in the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections, Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester NY.