Composers in Movieland

Modern Music: A Quarterly Review, Vol. 12, No 2, 1935

Official Publication of the League of Composers © 1935

The technic of writing motion picture music is complicated by many elements unknown to the musician of yesteryear. First of all the average theatre, ballet or opera composer of the past had to contend only with a few changes of scene, whereas the motion picture flies out of space and time, from cut to cut and second to second. How is one to illustrate a background flashing from galloping horsemen to pastoral scenes and on to three or four other varied shots? Writing two measures gallop music, one second pastoral music, and so on to the end of the film will obviously not answer. Neither can one ignore what is happening upon the screen and work away at a symphonic form hoping somehow to secure a metaphysical background or the sense of what is going on.

It is apparent that cinema music, to fulfill its primary purpose, should be descriptive and local. Yet if it is to be music at all it must achieve organic unity, whether by symphonic treatment, or some other method of restating and developing original thematic material. Either the score stands on its own feet as music or it falls into the category of pastiche, which is the destiny of most Hollywood film music.

Now there is only one way to achieve an “authentic” original score, and that is to give its production into the hands of one composer, who, from his conference over the first script with the film producer, plans all his work, and solves all his problems. This is so obvious that it seems hardly necessary to reiterate or explain. Indeed it is the method which has given us the only noteworthy film music to date - Georges Auric's score for René Clair's A NOUS LA LIBERTÉ, Ernst Toch's music for THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV, Eugene Goossens' for THE CONSTANT NYMPH, Serge Prokofieff's for THE CZAR WANTS TO SLEEP, Dmitri Shostakovitch's for ODNA, Kurt Weill's for the filmed DREIGROSCHENOPER. But these musical films are, it will be seen, all European. Until recently the method was unknown and untried in America.

For Hollywood has a group formula for making music. Every studio keeps a staff of seventeen to thirty composers on annual salary. They know nothing about the film till the final cutting day, when it is played over for some or all of them, replayed and stop-watched. Then the work is divided; one man writes war music, a second does the love passages, another is a specialist in nature stuff, and so on. After several days, when they have finished their fractions of music, these are pieced together, played into “soundtrack,” stamped with the name of a musical director, and put on the market as an “original score.” This usually inept product is exactly the kind of broth to expect from so many minds working at high speed on a single piece.

It is well to consider the economic factors in motion picture production which have developed this “forcing” process. If a picture needs music at all, it usually needs it badly when the film cutting time is over. It is at this advanced moment that the score must be “dubbed” into the picture, that is, run in final orchestral form into the first “soundtrack.” Joining the film now, the score cannot afford to miss the mark; it must fit the picture like a glove and be fairly descriptive of the important highlights. Otherwise it will endanger a previous outlay of several hundred thousand dollars spent in taking and cutting about four hundred thousand feet of film. Every minute longer that it takes to “dub” the final score into the picture, and so delay its release, will cost the film company the interest on its tied-up capital - which may amount to one thousand dollars a day. Thus it is cheaper to keep a staff of composers on salary, ready to produce a score overnight if necessary. Since each studio produces many pictures, a music department helps to make the producer's investments immediately profitable by expediting the film releases.

But recently a new factor has come to disturb this ideal balance of speed and expense. The group method of patching up a score was developed in the early days of the sound-films, before it was necessary to write “original” music. Ten years ago existing musical scores were not protected by copyright from this medium. The only expense producers incurred was the cost of having able copyists go to the music libraries or buy sheet music. The contents were available to them without royalty costs. It was thus that the method of “pastiche” became so recognized. Nothing could be easier, less time consuming or cheaper than to have a corps of men take a little of this or that, all well tried and of proved popularity, and fit the excerpts to a picture.

But now that copyright has been recognized as protecting composers against the sound-film, it costs the movies big money to quote twelve bars from anything or anybody - an average of $100 a measure. Think of a hundred thousand measures, and you will have some idea of the cost of a quoted score, and you will also understand the sudden new vogue for “originals.”

There can be little doubt that the demand for “original scores” is an excellent augur for composers. For it becomes obvious, even in Hollywood - perhaps after the spectacular successes of René Clair here and abroad - that the best original scores must be written by original composers - in other words that they must be composed. Already feelers are being put out from Hollywood in the direction of one-man scores. Naturally when such scores are tried and prove commercially popular, the mechanical organization of the music departments and studios will be adjusted to new methods of score production. And these will be developed on a sound economic basis as effective for speed and expense as the old ones - perhaps even more so.

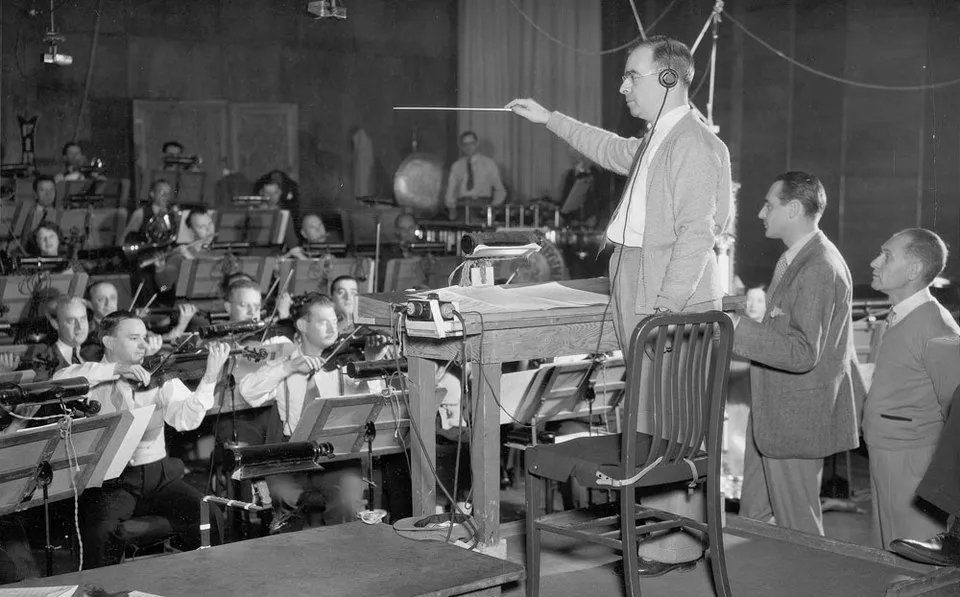

Such an experiment, on a large scale, has been undertaken, as is already well known, by the Eastern Paramount Studios, under the direction of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. Besides being successful in literary and dramatic fields, they are practised men of the movies; since I am associated with their venture as composer and music director, it has been necessary for me to substitute a method of procedure for the standard practice of the Western studios. The method is necessarily experimental, but as it has already been put into effect, and is to be continued throughout the series made at the studios this spring, I will outline it briefly here, for those composers, motion picture people, and laymen who, I presume, have an interest in the development of the sound-film.

When one man writes the score of a film (as I did for ONCE IN A BLUE MOON) it is advisable to have as much of the score finished as is possible by the final cutting, or on the day when the music department receives the film. This reverses the Hollywood process, and for good reason - there will be no seventeen or more co-writers to rush into the job at the last moment. The first step toward this accomplishment is an exhaustive preliminary discussion with the director before the film is begun, at which copious notes should be taken of the planned situations, shots, montages, movie leitmotifs. With this as background, and the first script at hand, a musical “break-down” can be made, which is movie parlance for a work chart. The script is broken into purely musical items, timings, work-out valuations, and sequences from the viewpoint of leitmotif. The tiny changes from shot to shot should be disregarded in planning the large sections and the thematic material of the score. To avoid the creation of a commercial pot-pourri, it is necessary to adjust the main musical outlines to the major psychological developments of the plot.

The break-down chart finished, the whole picture can be acted out by assistants in the music department, so that the timing of each shot and sequence may be recorded by a stop-watch. Such a framework of action and time is sufficient for the composer to undertake the work of score writing. This may then be carried on during the month or months spent in shooting the picture. The composer should naturally expect to write too much music and also be prepared for many changes from the original script. Daily, yesterday's “rushes” (which is all the film taken from the cameras in the previous day's shooting) are timed and can be checked against the original timing guesses, to gauge the length of any particular scene. When the first rough cuts appear, it may be apparent that a complete readjustment of the score is necessary, but usually guess-work methodically undertaken and checked will come within a few odd seconds of the timing for the entire picture.

Thus when the final film is cut and given to the composer, a great deal of the picture is not only in glove-fitting piano score but may be orchestrated as well. A final week is devoted to writing and orchestrating new sequences introduced by the producer at the last moment, or to any other sudden breath-taking, brain-exploding movie business. The “wipes” and “dissolves” and “fades” (which are various ways of blending one shot into another) are the last thing to be cut into the film; they make a slight difference in timing and must be reckoned with in the music.

By this technic, one week after the final cutting date a composer may complete a score which fits the picture. It is then handed to the copyists in the music department, twenty-odd men who work day and night for at least five days. Meanwhile orchestral rehearsals are begun on the first reels. In the big sound recording rooms the orchestra plays and two or three “takes” of each reel are made. Sometimes the picture is played while the recording goes on, sometimes not, depending upon how many small changes in tempo are necessary to hit various high spots “on the nose.” When the whole picture is “hit on the nose” musically, second for second, and each reel is “in the bag” the new sound tracks go to the laboratories and are developed, and the next day the best tracks are selected for the final “dubbing.” This highly technical process involves the putting together of the silent film, the speaking and original sound track taken with it, and the new music beneath it. When there is no dialogue the orchestra plays forte enough, and when the action demands, the track can be “squeezed” to pianissimo.

The master print is then ready. The negative film is matched exactly, and from the master negative thousands of prints are prepared for thousands of sound film theatres all over the world.

These are, to sum up, suggestions for a technical routine by which a single composer may adjust his work to the exigencies of the high-powered, speeded up methods of sound film production. There are, however, a number of other technical processes, of which it is well for him to gain some knowledge, in order to be properly effective in writing film music. Musical movies obviously touch on the fields of opera, radio, ballet and symphony. To be a fair film composer, some musical stage experience is almost essential. The cinema is first of all theatre and, to get anywhere with it, it is important to develop a theatre sense for musical background. As it is frequently necessary to exploit the human voice, it is also well to know something of its limitations and effects in the theatre.

Since THE GAY DIVORCÉE, a film with a star dancing straight through the picture, the ballet has become a factor of first importance to the movies, and to the composers, for obviously this is the kind of film for which carefully planned music will be most essential. It is almost impossible to realize the amount of planning and synchronization necessary in this kind of movie. It would be technically easy if everything were taken in “long shot” with the accompaniment of a symphony orchestra directly upon the set. But in reality it is taken in many shots - to get variety - by different cameras, not all at the same time; the symphony orchestra is dubbed in afterward. Music for the dancing is ground out by a piano, according to a plan devised by musician, choreographer and producer. Only when all portions of the silent film (recorded to the piano score) have been cut and assembled, is the orchestral score played into the accompanying sound track.

Perhaps the most highly specialized technical knowledge that must be acquired is that of the microphone - which one may gain through writing for the radio. Everyone knows that the microphone-orchestral balance is something utterly and completely different from that of the ordinary orchestra. The clarinet sounds much like an oboe, and so the two must be used together only with the greatest care. The horn and cello waves “fuzz” one another if they approach within certain registers. Percussion of indefinite pitch must be either fortissimo and far away from the “mike” or pianissimo and very near, otherwise it blurs. You can reduce the number of lower strings but not the upper strings. Third woodwind parts sometimes sound better on the harmonium. A great deal of care must be taken with the seating arrangement; “condenser mikes” or “ribbon mikes” change the whole effect.

In movie work you need this knowledge if you have ever needed it. A movie recording can be better than a phonograph recording; it is not the result of accident but of a score carefully planned for the purpose. The phonograph companies cannot always have scores written, but must take them as they are; the cinema gets, not an orchestral score, but a planned microphone-orchestral score, intended for one purpose alone.

Obviously it takes a great deal of planning and patience to make even a bad movie. With the technical side of the cinema so complex, and the expense at every step so vast, it is to be expected that producers should be reluctant to entrust the work of score making to others than their highly experienced music departments. But there can no longer be any doubt, with the general rise in the quality of films, that a way will be found in America to introduce serious composers into the business of sound-film production, which should prove as legitimate and fruitful a field for them as it is for writers, actors, directors and dancers. Constant Lambert has truly said, “Films have the emotional impact for the twentieth century that operas had for the nineteenth. Pudovkin and Eisenstein are the true successors of Moussorgsky.”