An Interview with Steven and Annemarie North

An Interview with Steven and Annemarie North by Daniel Mangodt

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.10 / No.40 / 1991

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

In 1960 I saw THE WONDERFUL COUNTRY in a small cinema in my home town. Although I was only 10 years old at the time, I’ll always remember the impact this film had on me. One scene became engraved on my memory, where the injured gunman (Robert Mitchum) rode into a windy, half-deserted border town. Today this scene is still an example of suggestive film music composing.

From then on, Alex North became one of my favorite film composers (although I didn’t even know his name at the time!), along with Rozsa, Bernstein and Jarre. I grew up with big epics like BEN-HUR, SPARTACUS, LAWRENCEOF ARABIA, and in those days cinemas sometimes respected the American roadshow way of film presentation. I saw KING OF KINGS with the overture, while the curtain was closed and enshrouded in a mystical blue light. Wonderful!

When I heard of Alex North’s death, it was a sad moment for me. I had fought with Spartacus against Crassus, fallen secretly in love with Varinia and even with Cleopatra (there is no accounting for tastes…) and I learned to appreciate Michaelangelo’s work thanks to THE AGONY AND THE ECSTACY. Never have Michaelangelos frescoes been so musically illustrated as in this film.

At the Ghent Film Festival the newly restored version of SPARTACUS was presented and I didn’t want to miss this presentation in old Hollywood style, complete with overture, intermission and end title music. Even if only 10 extra minutes had been restored, the experience was as grand as seeing the “new” LAWRENCE OF ARABIA two years ago. I have lost count, but I must have seen SPARTACUS more than 15 times by now.

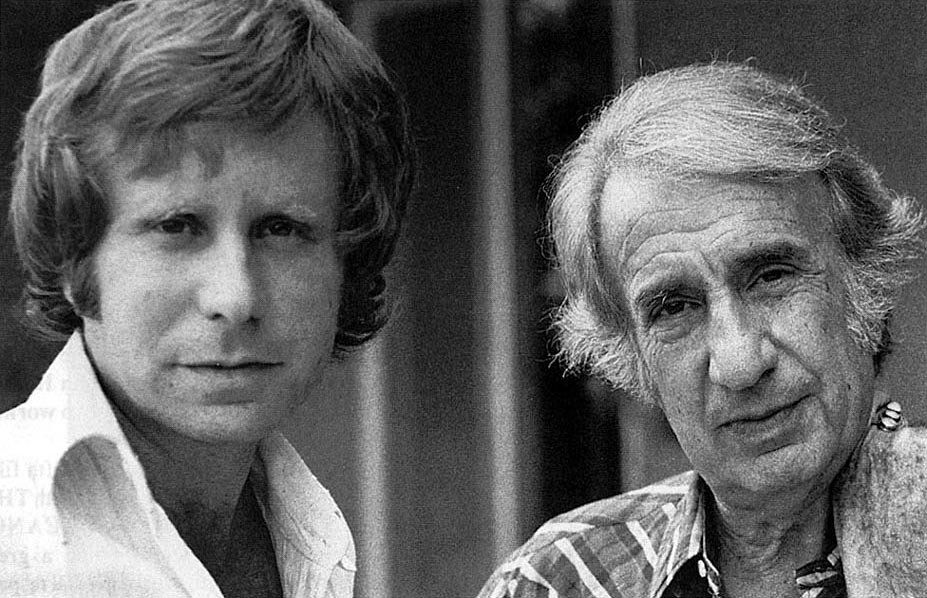

At the Festival I also saw North’s last film, THE LAST BUTTERFLY, and I was able to interview both Alex’s son, Steven, (who produced THE LAST BUTTERFLY) and his widow, the German-born Annemarie.

When your father was scoring THE LAST BUTTERFLY, did he discuss the music with you?

Steven North: THE LAST BUTTERFLY was originally conceived in 1981, as a picture with Marcel Marceau (the mime artist). My father had scored a film I had produced in 1973 called SHANKS with Marcel and he started thinking about the concept of the film 8 years before the actual film was scored. He came to Prague when the film was first planned in 1983, and worked with Karel Kachyna, the director, on concepts for the music and what kind of thematic ideas Karel had in mind. So he actually had a few years to think about the project. The project then collapsed financially and it took me another 6 or 7 years to put it together and of course he had stored away his notes, his scribblings.

When you see the film, you will see there are some ballet sequences, and there are certain things that are choreographed to music, so he had actually written the music for the choreographed portions of the film, that were going to be played on the piano while we were shooting, and then re-recorded in Prague at the end. So those themes had been written much earlier than the film was actually made. Eventually the film was set up, first with Ben Kingsley, but that didn’t work out and eventually with Tom Courtenay.

Did the director adapt his movie to the music?

Steven North: Some of the themes had been written, but then my father by 1989 was quite ill. So he worked with another composer, Milan Svoboda, who is a Czech composer. There was a collaboration, because he was not well enough by the end to write the big pieces that were finally used in the picture. The entire dramatic score is Alex North’s and the choreographed pieces are by Milan Svoboda.

Did you father talk to you about his music?

Steven North: We talked about it, but I left home when I was very young, so we didn’t have that much chance to talk about his later scores. One of my proudest moments was when John Williams, discussed the score for VIRGINIA WOOLF at my father’s funeral. I remember very distinctly being at the university at the time, and saying to my father that I thought that a baroque score with a guitar would work for the picture, because it took place on a college campus and my father – I guess – took that to heart and eventually wrote a very beautiful score for guitar.

North loved working for difficult, theatrical subjects…

Steven North: I think he loved working for the theatre, for plays that had been adapted. Arthur Miller always said that Alex North captured the spirit of Willy Loman in his score for DEATH OF A SALESMAN. And they were able to work again on THE MISFITS. He felt that he caught the spirit of Nevada, and the spirit of these lost souls. So he was always trying to establish in his music what the playwright or screenwriter was trying to establish with words.

This year they released the restored version of SPARTACUS.

Steven North: Sadly he never saw it. He was not well enough to go and see it. However SPARTACUS was one of his favorite scores for several reasons. First of all, Kubrick allowed him a year and a half to write the score, which is exceptional (the producers give a composer six weeks to write a score now), so he was actually working on it from the very beginning, but more importantly it was a novel by Howard Fast, who had been blacklisted; it had a screenplay by Dalton Trumbo, who had also been blacklisted; and my father was living in Paris and his passport had been taken away by the State Department. In fact he was given special permission to come to Brussels to write a ballet for the Brussels World Fair in 1958, so Brussels had a special meaning to him, and this picture broke the blacklist as it were, in that it brought him back to America. Together with Fast’s name and Trumbo’s name, it was a very important picture for him both politically and artistically.

Was your father politically motivated?

Steven North: Yes. In the 30’s he was very involved in left wing movements. He had been very close to Elia Kazan, but Kazan gave names, and my father refused to give names. From the day Kazan actually testified in front of the Un-American Activities Committee, my father never spoke to him again until the end of his life.

Your father was never under contract to a studio?

Steven North: He never signed a contract with a studio. He was asked various times in his life to join Twentieth Century Fox, to join CBS at one time. He wasn’t a joiner. I don’t think he was a member of a club, or a political party in his entire life. I think he voted republican, democratic or communist depending on who the candidate was. He never signed a contract with a studio, nor with anybody else. He kept his independence.

How did he react when a director asked for a certain kind of music? Did he give in or did he follow his own view?

Steven North: It’s interesting, that question, because, if you look at his career, with the exception of Martin Ritt and Daniel Mann, most of the directors he worked for, Zinnemann, Kubrick – Kazan he did 2 pictures for, but the reason they split was political- most directors he worked with only once, because he had a very independent view of how to score a picture and very often he rowed with the director. In fact Alex had barred Mike Nichols, the director of VIRGINIA WOOLF, from the stage at Warner Bros., because Mike wanted to continue to make changes in the score and my father was so convinced that he was right about the score that he wouldn’t allow Mike Nichols on the stage. Jack Warner actually came down and made sure Mike wasn’t allowed. It was Nichols’ first film, so at that point my father had some say. But he never worked with Mike Nichols again. He worked with directors like Lumet, Zinnemann, because he was very strong in his feelings about how things should be done.

He did work several times with director John Huston…

Steven North: Huston and Alex were very close. Huston he did 5 pictures for. John and Alex seemed to see things almost identically. In other words John would have an idea for a film, let’s say an operatic approach as in PRIZZI’S HONOR and my father would sit in the screening room and say to John before John mentioned anything: I think this should be done with an operatic approach and John would say: I can’t believe it Alex, that’s exactly what I had in mind. My father did THE MISFITS and then he didn’t work for John Huston for many years, because my father saw THE NIGHT OF THE IGUANA, which had been offered by John Huston and he told John he thought it was a terrible picture and didn’t want to score it, and John didn’t want to talk to him for several years. So he was very strong in his opinions.

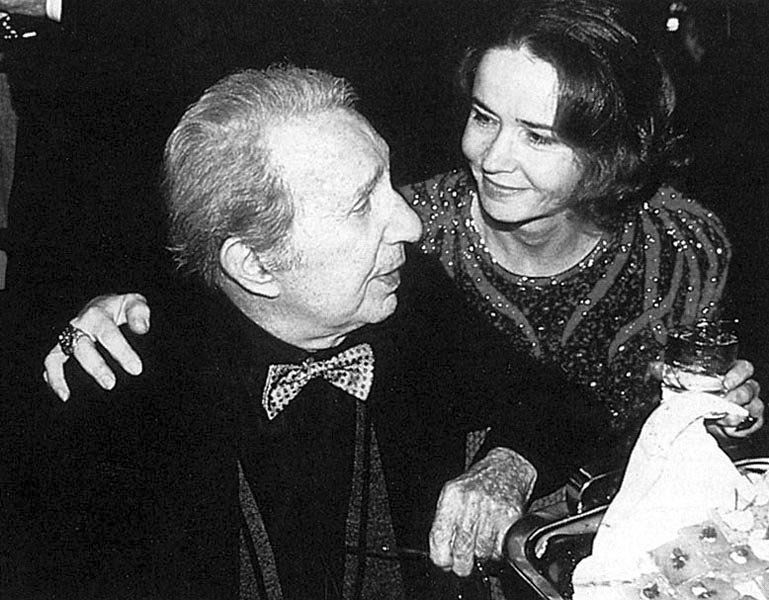

Mrs. North, how did you meet our husband?

Annemarie North: I met Alex North in 1967. I was working then for an orchestra called the Graunke Symphony Orchestra in Munich, which was then the only private symphony orchestra. It was very interesting working for them: I did secretarial work, translations, setting up concerts, film recordings. The orchestra needed the extra money, it wasn’t fully subsidized. Most of the big orchestras in Germany are, thank God, so they can survive. So we needed the film music and that was an input I had a lot to do with. And Alex came to do his AFRICA, that ABC had commissioned him to do and he had an enormous orchestra of 108 people. We had over a week time to do that, which was quite unheard of. Usually the composers from Hollywood would come and everything was set up and do it in a couple of sessions and it was always rushed. Not so with Alex. He took his time. He came in, everything was prepared and it worked beautifully. And the orchestra members had enormous respect for him.

Alex North wrote music for big orchestras, but he also wrote for small ensembles. Which did he prefer?

Annemarie North: I don’t think he had a preference. What he always wanted was to write music for films where he was able to relate to the characters. The big epics weren’t really his big love, although he got to be known for them. At one time it seemed he was the one to do SPARTACUS, CLEOPATRA and SHOES OF THE FISHERMAN, but he sure loved these small, little combinations, especially when he did A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, he always told the story that Ray Heindorf asked him, “What’s the matter with you, you have the big orchestra available. Use it. They are here for you.” He said, “No, I want to make a dramatic point, and I want a change.” He had a different concept and he used a very small group. And everyone knows that: the breakaway from wall-to-wall writing like the old Viennese school (Steiner, Korngold). He also tries to underline the characters musically in SPARTACUS. That’s the mark of any good composer.

Did he discuss the music with you when he was writing?

Annemarie North: No, not really. Most often he worked like this: he would always read the script and then go and look at the film. He really preferred to know what the story was about before he even met with Alex North Remembered the director. After he’d read the script and seen the film, they would discuss it. But he usually had a concept pretty much when he walked in, which way he would go and if he was lucky to find a director that would go along with him, then it was an easy ride. If he didn’t, it was a different story.

On THE LAST BUTTERFLY, the orchestrations were by Alexander Courage. Did he usually use an orchestrator, or did he prefer to do everything himself?

Annemarie North: No, he wrote it out before, absolutely. It was almost not necessary for him to have an orchestrator. But then again the copyist couldn’t take it out of the score; it had to be put together. There were very distinct directions although he did work with Courage, Maurice De Pakh, David Tamkin, and these are big names in the industry. They worked totally together and he appreciated their input very much. They always used to say that he almost didn’t need an orchestrator. The score was almost completely written.

Alex North received 14 nominations, but he never won an Oscar. Did he regret that?

Annemarie North: I don’t think he regretted it so much. It became almost a joke, you know! When you see the kind of competition he was up against at times… If a picture had a big song in it, then the majority would choose for that. The most important thing for Alex was that his peers respected him and after all you are being nominated by your peers. Being nominated is sometimes more important, because these people know what they are talking about. Also he refused to campaign. Other composers would campaign, go to parties, wine and dine with producers. If it was a picture for a big studio like Warner Bros. or Fox, and they had music and de it was very prestigious to them and they would go behind it and make a lot of hoopla. But Alex couldn’t deal with that. He was beyond that. Some of the industry made up for that when they gave him the Life Time Achievement Award Oscar in 1986, and he is the only composer so far to receive it.

Alex North kept working, in spite of his illness…

Annemarie North: It was an amazing feat that he was able to work at all. The week before he died he called his agent and said, “What’s the matter with you? Why don’t you get me a job, I need to work, I need to earn some bread for the family.” Indeed up to the very end he had offers; he was supposed to do THE GRIFTERS and GUILTY BY SUSPICION.

Steven North: Scorsese always said Alex was his favorite composer, but he never worked with him (laughs). He found THE GRIFTERS too violent.

Annemarie North: Not only that. The doctor said it would be too stressful for him.

He also felt DRAGONSLAYER was too violent…

Annemarie North: Not really. DRAGONSLAYER was a fairy tale. What he didn’t like was that Robbins, the young producer, wanted him to depict certain action on the screen with drum rolls and that kind of stuff. Alex said: “This may be a Disney picture, but we don’t have to mock it.”

What was his view on electronic film scoring?

Annemarie North: He thought certain effects were effective, but he didn’t really like it very much. Also the use of rock scores. You can’t really call it a score. They just use songs. But that is the trend in the industry and it sold a lot of records and consequently when the studios were taken over by the money people, the interest wasn’t in art any longer. A good artist like Alex would of course suffer by that.

CARNY had music by Robbie Robertson on one side…

Annemarie North: But Robbie Robertson at least is an artist. He knew what he was doing. It was a wonderful collaboration. They adored each other. There’s a wonderful story. I was sitting in the booth and they were doing the main title where Busey sits and makes up his face as a clown; Robbie Robertson and Busey were standing next to me and they didn’t know I was sitting there and was listening to what they were saying. Busey said, “Jesus, Robbie, listen to this. Look at me. I didn’t know I was that good. This is incredible.” And Robbie patted him on the shoulder and said, “Now you know why I wanted Alex.” It was just that innate, instinctive quality Alex had to bring out of these characters as he was underplaying them with music. It’s really a tremendous gift. Alex always said you had to work with the characters, and hit the subconscious of the audience, but not take it away. Let them do it.

Alex North usually conducted his own scores?

Annemarie North: It varied very much. Alex truly preferred to be in the booth and listen to what the input was, where he could control the engineer and he thought that was a better situation, rather than conducting and then coming back in listening and having to change it. It worked sometimes, sometimes it didn’t. I’ve also been in a position where I watched him where the conductor didn’t bring quite the quality he wanted and he had to go out and do it himself, and then they adjusted it in the booth. On the whole I would think he preferred not to conduct. That had also to do with his shyness. He didn’t like to go in front of a crowd. That was always difficult for him.

There were certain conductors he trusted, Alfred and Lionel Newman, for instance. For VIVA ZAPATA they worked on the main title for a whole week. It’s extraordinary the amount of time they had available then. Listen to SPARTACUS: its quality, the nuances, and the definition. You don’t hear that today. Now you record a score in 2 or 3 sessions and that is already too much. One cue, run through and the next one is a take. Well, look at THE MISFITS. The studio was pressing to have an early release, before Christmas, in order to get it for the Oscars and because 2 of the 3 actors had already died. They wanted to use all that publicity. And Alex said to John Huston, “I can’t do this picture justice. I can’t produce a score in such a short time,” and Huston was strong enough to say: “That’s all right, don’t worry, I’ll fix it.” And indeed he did. With a lesser known director it would have been a problem. Then again the quality would have suffered. Maybe Alex wouldn’t even have done the picture!

Did he work on the restoration of SPARTACUS?

Annemarie North: No. They did ask him but Alex felt there wasn’t really much he could do. When they were going to remix it, they called him up but he said: “The engineers are so good, it’s not really necessary for me.” He was quite sick then and mixing is a very tedious job.

Did he rewrite some of his scores for concert pieces?

Annemarie : There are only 2 or 3 that exist, unfortunately. He always meant to do it, but by the time he had finished one he was really quite bored with it. It’s a shame, because we get questions from the Boston Pops, the Cincinnati Pops. All these orchestras now have film music programs. His scores are not available now, but we’re trying to put that right. Christopher Palmer is going to make little suites out of various important scores. That’s our future project.