An Interview with Maurice Coignard

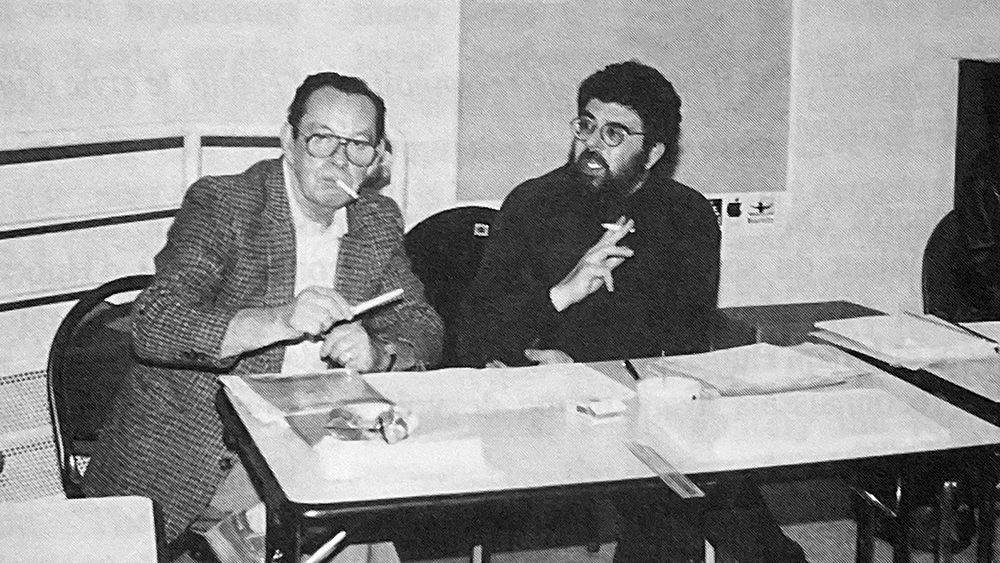

Maurice Coignard and Gabriel Yared in Biarritz

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.13 / No.50 / 1994

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

Maurice Coignard was Georges Garvarentz's closest collaborator for many years. As arranger and orchestrator on over 150 films, he continues to collaborate with France's leading composers. Invited to the “Écrans Sonores” Festival in Biarritz, he has drawn on this experience to write an educational book on the art and craft of composing and orchestrating film music. This unique work, with a preface by Gabriel Yared and Jean-Claude Petit, was published by Max Echig under the title “La Musique et l’Image”. Maurice Coignard was kind enough to invite us to talk about his profession and career.

Could you tell us about your musical background…

I began my studies at the Paris Conservatoire. My ambition was to take part in the Rome competitions and write oratorios and operas. But when I graduated with my diplomas under my arm, I realized that I'd made a mistake and that I didn't know how to do anything! Then I met a jazz conductor, Noël Chiboust, who gave me my first chance. So I did orchestrations for a Glenn Miller-style orchestra, and everything I'd learned at the Conservatoire was of no use to me. I'd studied harmony, counterpoint and fugue, and then I found myself swinging. But I liked it. Then I joined Chappell Editions, for whom I orchestrated all the American standards of the time over a four-year period. It was during this period that I met film music composers who asked me to work for them. That's how I found my way into film music, and I haven't stopped since.

How would you define the terms arranger and orchestrator?

The orchestrator is given a score in the form, for example, of a piano part on 3, 4 or 5 staves. All the music is written, harmonized and synchronized. All he has to do is agree with the composer on the choice of instruments and their timbres. There's no creative work involved, but it's exciting! The arranger, on the other hand, has a very complex job, all the more so when the composer is self-taught. Often, all he has to start with are snatches of themes, which he then has to develop and harmonize. In other words, he has to create all the background music for the film, based on elements he would rather not have had. That's what's known as being a “ghostwriter”, and it's not glorious. He stays in the shadows all the time, lending a hand to the “broken arms”. I've got out of that role and now only do orchestrations, and I'm very happy about that. If I have to compose, I prefer to do it for myself, but unfortunately I don't have the time.

How did you feel about working in the shadow of other composers?

Badly, of course! But I didn't have much choice. Having said that, for the past 10 years I've been lucky enough to work with composers who consider me a collaborator and mention me alongside them in credits and on CDs. Today, I can no longer consider myself to be in the shadows. Now that I'm experienced, I'm in a position to turn down uninteresting business. To get to this stage, it takes a few years and no longer chasing after a fee.

You say that composers now mention you alongside them. Do you think this is legitimate?

It's a nice thing to do, but it's not an obligation. And then, there are cases where the composer is supposed to have done everything and so we don't appear, so as not to offend certain sensitivities. But it's true that when that happens and my name is associated with one of the “greats”, I'm happy. It's a reward. There are other types of recognition too, such as the one I received for the film LES MILLE ET UNE NUITS when Gabriel Yared introduced me to the Orchestre de Paris, saying, “It was Maurice Coignard who orchestrated all the music, because I didn't have the time to do it.” Jean-Claude Petit and Pierre Porte are also at the same level, but not all of them are.

At what point do you intervene in the composer's work process?

Often, when the composer doesn't have enough time to do everything. In the end, I live off their delays! But in general, they're not philanthropists, and if they make me work, it's because they can't do otherwise. It also happens sometimes that they're not inspired by a given scene. That's when I write it. But I don't know any composer who's made me work because he was fed up with writing. They're all passionate when they're composers in their own right.

Do you ever go beyond the scope of your profession?

Yes, I have written for others. But then again, they didn't have the time. Among other things, I made a 6-hour TV movie. It was an important assignment, and the composer involved had asked me whether he should accept or refuse, even though he wouldn't be around to write it. I advised him to take the job and wrote it for him. I did him a favor, and as far as I'm concerned, it's legal. It's supply and demand, and the arranger gets paid for it anyway. You just have to make sure that it doesn't become systematic.

What is your working technique?

When I started out, I did music no.1, no.2 and so on, and I've completely changed my technique. Music no.1 often corresponds to the credits, and I write it at the end. What's important is to keep moving forward, because deadlines are often very tight and there's nothing more distressing than repeating the same piano phrase all day long with a theme that doesn't develop. Now I start with the music that works best. What you can't find on Monday will be easy on Tuesday.

How much time is usually needed?

I knew the “heroic” days when you only had 8 to 10 days to get everything done, at a rate of 18 hours a day. It was a real mess, but thank God it's turned around! You have to remember that the film has already been made, and the recording and mixing dates fixed in advance, with a very tight schedule before the musical score is written. Just imagine the work involved. For example, for STAR WARS, which contains millions of notes, they needed three months and five orchestrators - and there weren't too many of them! But in eight days you don’t have enough time to compose a good film score. Even less so with a large orchestra…

Is it easy for you to adapt to different musical trends and new sound techniques?

You always have to keep up-to-date with new trends. I started with the predecessor of the synthesizer, the Ondes Martenot. It's an instrument I'm particularly fond of. Unfortunately, it's been overtaken by synthesizers because it's monophonic. When I was asked by a composer to use Ondes Martenot in an orchestration, I used 4 of them to overcome this problem. This quartet was magnificent! The result was all the more surprising, as it was to play a bossa nova! As far as the synthesizer is concerned, I use it a lot, but it's a new element that shouldn't be used to replace a trumpet, a violin, etc. It's to be avoided. That's a no-go. On the other hand, it considerably widens the sound field and goes very well with the symphony orchestra.

Is there a genre in which you feel particularly comfortable?

Definitely the symphonic style. Ultimately, it's easy, because all the instruments you want are there. It's more difficult to write for a quartet, because you're limited in terms of timbre. It's one of the most complex forms... With a large orchestra, the sound palette is obviously richer, but it takes a lot of time to write the score.

Can you save a film?

Yes, I think so. But the opposite can also happen. It's worth pointing out that a good score will never save a mediocre scene; on the contrary, a thundering, old-fashioned score can do considerable harm to a good film, especially several years after its release.

Can you add anything special to a score?

I do everything along those lines. When I can add something interesting, I do it with the composer's agreement. That's what he expects of me, if it's necessary to make the result better.

Is it possible to recognize an orchestrator's style by listening?

Yes, but you need a trained ear. Sound engineer William Flageollet recognizes Hubert Bougis's style and mine without making a mistake. I too am rarely mistaken, and when Hubert Rostaing was orchestrating for Philippe Sarde, I recognized him even before seeing his name mentioned in the credits.

Does your profession have a future?

No, not at all! It's a profession that's disappearing. People no longer say, “I'm going to be a film music orchestrator.” Today, it's a group job. What I do in the symphonic niche no longer exists in France. There must be four or five orchestrators left. I'm part of the last guard, and what I'm trying to do is pass the baton to young composer-orchestrators, as I was given the opportunity to do at the Biarritz Festival. They're keen to learn how to do it, but there's no specific training in writing film music... To make up for this shortcoming, I wrote an educational book entitled La Musique à l'image, published in March 1994 by Editions Max Eschig.

Can you tell us a little about this book?

It's a checklist that covers everything: the instruments, their tessituras, their possibilities... There are examples of the most diverse musical styles, from Viennese waltz to Hollywood style. You need to know how to write and orchestrate all these things, for which there are techniques and examples. There are other things too, such as how to orchestrate a piano phrase for several instruments. I also talk about all the possible combinations of timbres, as well as what not to do. Even if there are no rules in this field, it's still possible to give advice.

What advice did you give your students at the last Biarritz Festival, and what do you remember about it?

I have excellent memories of it, of course. It was the second time I'd been there. The idea for my book came from the notes I'd prepared for the classes the previous year. I already have plans for next year. The trainees have all been enthusiastic, and I'm always delighted to bring them something. I pass on to them what I've learned from experience and explain all the blunders I made when I was starting out, so that they don't make mistakes.

What would you say to young people considering this profession?

That there are two fundamental axioms. (1) All orchestral timbres are beautiful. (2) All compositions must be written in such a way as to be easy to perform. The study of orchestration comes after the study of harmony, counterpoint and fugue. After that, the best schooling is to read and listen to the works of the great masters. Organizations such as SACEM should be encouraged to provide a specialized film music room, complete with scores and CDs. The mistake young people make is to buy a synthesizer and think they're a great composer within 8 days. As Gabriel Yared says, “If you learn the alphabet, which has 26 letters, you can make the effort to learn music, which only has 7 notes”!