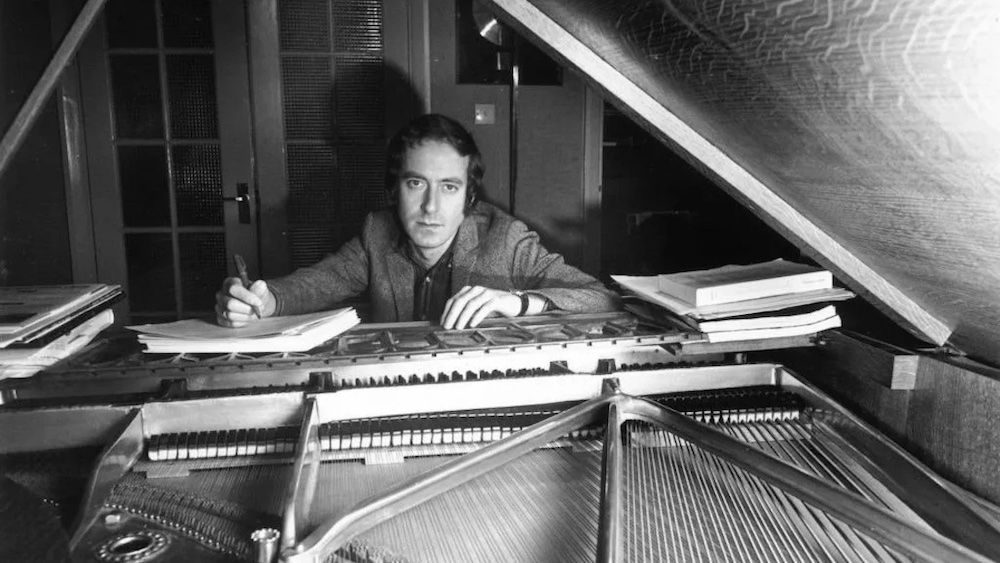

An Interview with John Barry

An Interview with John Barry by Daniel Mangodt

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.15 / No.58 / 1996

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

You have scored 11 out of the 18 James Bond films. Looking back on that period in your career, how do you feel about it?

I enjoyed doing it. If you do one movie you get one shot at it. It’s like having 11 shots at the same movie. So it was interesting, developing the style over a period of time. I think by the third movie, by the time I was doing GOLDFINGER, the style was consolidated; not only from the musical point of view, but also from the directorial point of view: the pre-title sequence, the main title sequence, the song idea, Ken Adam’s design… I think by GOLDFINGER everything fell into place. It was an exciting time, you know, the sixties. It was a hugely successful series; the most successful series in the history of the cinema. So it was very exciting to be associated with it.

You relied on several themes: the James Bond theme and the 007 theme, but each time you had to add something new.

Each movie had its new song theme, apart from the James Bond and the 007 theme, which we repeated down the line. We always had a new song and that song was developed throughout the movie, plus new material for the action sequences or whatever.

Parts of each score were based on a song for thematic material…

I always liked to have a song that one could develop and use throughout the score, rather than having a song stuck at the beginning of the movie that hadn’t any relationship really to the rest of the thematic material. I like the song to be an integral part of the whole picture. It must have a function; it must have a musical content.

The song is usually introduced over the main title sequence with the Maurice Binder graphics. What was your working relationship like with Mr. Binder?

It was to and fro. He used to show me rough cuts that he had done or rough footage of each shot and I would play him some of the music and we would settle on the idea of tempo. It was a back and forth thing and so finally the whole thing came together.

Each time there was a different singer, except in three cases: GOLDFINGER, DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER and MOONRAKER were all sung by Shirley Bassey.

At the time of GOLDFINGER, Shirley was the number one singer in London – she hadn’t reached an international audience, but she certainly was big in England. She did such a great job on GOLDFINGER, so when DIAMONDS came up, we decided to use her again. MOONRAKER was an accident actually. We had someone, very big, an American male singer, who sang the song first, but for some reason, it just didn’t work out and we were in a rush. We had a time problem. We recorded MOONRAKER in Paris and we were back in L.A. The following day when we decided this American singer was not working for us – through no fault of his, it’s just one of those things – I was having lunch in a Beverly Hills hotel and who should walk into the lounge? Shirley Bassey. I didn’t even know she was in town. I invited her and had Cubby Broccoli on the phone and we were in a studio within a week. It was virtually the same arrangement, everything the same and we were very pleased.

You worked with Lulu, Tom Jones and Nancy Sinatra. Did you adapt the song to the singing qualities of the performer?

When Leslie Bricusse and I worked on YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE, we didn’t have any idea who was going to sing it. I went to L.A., because Leslie was working there and we worked on the song. Nancy had that big hit: “These Boots are made for Walking” and we asked her to do it. We sent her a tape with the melody and she agreed to do it and she came to London. I remember – I’m sure she won’t mind me saying – there were quite a few edits. I think we used about 23 different takes. Through the miracles of technology we were able to put a song together and it worked out fine.

On the last couple of films you were not so pleased with the results…?

I was pleased with the Duran Duran, situation. It was the first time I worked that way, with a group. I usually would write the melody, and then bring in the lyricist. People would say: What comes first, the music or the lyrics? With Duran Duran it was the drums. That’s the way they work. They put the drum track down and then we worked in the studio together and we concocted the melody and Simon Le Bon wrote the lyric. Their way of working was unusual for me, but they were really a terrific group of guys and we were very happy with the result.

With a-ha that was really a difficult situation. They were doing concerts in London and we went to see them. They were just shrieking kids, but they were very successful and we met with them and they seemed very fine. But I found them very difficult. They refused to go to Pinewood to see the movie. I said to them: “Look, when we did” ‘We Have All the Time in the World’, Louis Armstrong had been in hospital for a year, he came out and we showed him the movie in New York. Everybody who had ever done a song has been willing to do that.” They had an attitude which I really didn’t like at all. It was not a pleasant experience.

My personal James Bond favourite is ON HIS MAJESTY’S SECRET SERVICE.

The action sequences were terrific. Peter Hunt (the former editor and second unit director) did a great job on it. They had a terrific drive. I like the score very much. If Mr. Lazenby could have been better…

You worked with Louis Armstrong on this movie.

It was wonderful to work with him. It was a line out of the book. Hal David wrote the lyric and when we were thinking who should do it, I proposed Louis Armstrong. It seemed a crazy idea, because we had always been working with younger artists. There is an irony about this song: ‘We have all the time in the world’ and it’s like when Walter Huston sang ‘September Song’. That kind of feeling, a different kind of reflection by an older person: We have all the time in the world when actually time is running out. So that was the thought behind that and we went to New York and recorded that with Louis Armstrong. It’s one of the most precious experiences I have ever had.

You didn’t score all the James Bond movies, some you didn’t want to work on, like NEVER SAY NEVER AGAIN.

I was asked to do that, but that was out of the camp.

What happened when GOLDENEYE came along?

That I didn’t do because I had commitments this past year: CRY, THE BELOVED COUNTRY and ACROSS THE SEA OF TIME, an IMAX 3D movie. Those were two projects I was really keen on and I just had a newly born son. So, I wanted to have time with him and enjoy that side of my life. I’ve been asked to do the next one, which I shall probably do.

Eric Serra’s score has been heavily criticized.

I saw the movie. They didn’t know who to go with. The producers talked to me about different composers. They mentioned Eric. I told them if they wanted to go in a different direction, they should do so. I had been away from the Bond movies about 5 years. So I said, try it. It might be fresh, but it’s a difficult thing when a certain style has been stamped on it.

On FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE you worked with Lionel Bart…

Lionel wrote the song. Lionel had just finished OLIVER, the stage musical, which was a huge success. My credentials at the time had been mostly as a musical director plus my instrumental hits, but nothing of a major nature. Saltzman and Broccoli wanted to have Lionel and I was happy with it. So Lionel wrote both words and music and I arranged and orchestrated it and we put the song into the orchestration, into the Bond vein.

You worked with Lionel Bart on several occasions: MAN IN THE MIDDLE and NEVER LET GO.

On MAN IN THE MIDDLE, he wrote a song and I wrote the rest of the score and on NEVER LET GO he wrote it under another name, John Maitland. It was a non-copyright version of ‘When Johnny Comes Marching Home’, which we adapted.

You worked with Bryan Forbes on six movies. What’s it like, working with him?

Working with Bryan was wonderful. It was nice to work with Bryan at the time I was doing the Bond movies. They were intertwined with Bryan’s movies which were totally in another area. I met Bryan when I did the jazz club sequences for THE L-SHAPED ROOM and used Brahms’s piano concerto as the main score and when I had finished that, he said he was planning a new movie next year with a strange kind of orchestration, SEANCE ON A WET AFTERNOON. I didn’t hear from him for a long time and then he sent me the script for SEANCE and I came up with this strange orchestra: four alto flutes, 4 cellos, I can’t remember how many basses I used, and percussion and vibraphones and just by that mix alone we got a very unique kind of sound; a very strange orchestra which worked very well for the movie.

KING RAT was the next, which was the first time I worked in Los Angeles. Bryan took me over there, much to Columbia’s dismay: “Why do you take this Limey composer to Hollywood, where we have so many good composers.” Bryan wanted to work with me. The difficulty was that I used an instrument called the cymbalom, a Hungarian gypsy instrument. It had a strange tone that I found appropriate for the movie; that with a string orchestra and woodwinds and we had this extraordinary player in London, John Leech, who was a wizard on the cymbalom and many other instruments. I remember asking the orchestral manager in Los Angeles if he had a good cymbalom player. Oh, yes. He had. Anyway, believe it or not, he was dreadful. I remember the first session we had, we didn’t get one minute of music in the can. It was very frustrating. We finally brought in a guitarist who gave us through the miracle of technology something bordering on the cymbalom sound. So don’t take anybody’s word for it. Always check it out.

You also did THE WHISPERERS…

That was an interesting project. I had a series of very successful records now and I went to see Mike Stewart, head of United Artists Music in New York and I asked him if he was going to put out this record. They would have to pay the re-use fees. I said: “Why don’t you put the re-use fees up front. Let me make the album of the music for the movie. Bryan would like to do that; he would like to have a score worked off the script.” So, we recorded the album before the film and we just made one or two adjustments in nature of the movie. The same happened on DEADFALL, with the romance for guitar and orchestra.

You also worked with Anthony Harvey on several occasions.

He was an editor. He edited some of Bryan’s movies and some of the Boulting brothers’ movies and he worked with Kubrick. He did a small film DUTCHMAN. He didn’t want any music in the movie at all and when he had finished it there were 3 areas where he wanted music: the beginning, an interlude and a closing section. It was virtually the same piece of music used 3 times.

THE LAST VALLEY and THE LION IN WINTER are two of my favourite Barry scores.

I’m sure I got THE LAST VALLEY because I had done THE LION IN WINTER. I love THE LION IN WINTER. That took me right back to my roots. I had studied harmony and counterpoint with the Master of Music at York Minster. People said: that’s strange, that’s different. Actually I went back to my roots.

You did the beautiful ‘Children’s Songs’ in THE LAST VALLEY.

Those were German texts. I had this gentleman in England called Edgar Fleet, who worked with various orchestras and on LION IN WINTER I asked him for various Latin texts. They were all old texts and I just set the music to them.

You worked with Richard Lester on THE KNACK, PETULIA and ROBIN AND MARIAN…

I had a strange relation with Richard Lester. I remember when I did THE KNACK, he said to me after I had done it: “You have done everything that I wouldn’t have done, but it works!”, which I thought was a nice kind of compliment. PETULIA was an interesting project. Nic Roeg was the lighting cameraman on that. I enjoyed PETULIA.

ROBIN AND MARIAN: Richard Lester had two scores by Michel Legrand: one was a double string concerto. I don’t know why, but under pressure from Columbia it was not the right score for this movie. Richard could not stay in Los Angeles, he had another movie he had started in London, and so it was telephone conversations. It was one of those rush jobs: I had literally (no time) from seeing the movie to recording it, because they had release dates. I had about four weeks to write it. I wrote it in the Beverly Hills Hotel, Bungalow 15 and I think Richard was happy with some of it and unhappy with other parts. It’s very difficult when you’re doing a movie and the director sits 6,000 miles away. Columbia were delighted with the score I did, a romantic adventure score.

The same happened with THE SCARLET LETTER.

I had 4 weeks for about one hour of music. One doesn’t like working like that. I happen to like THE SCARLET LETTER; I thought it was a good movie. Being a European I never read the book, but it’s an American classic and Americans have very strong feelings about the book, as I suppose the English do about Dickens. The happy ending shook a lot of Americans. The film had bad reviews, I think much unwarranted, and Demi Moore made some statement that nobody read the book anymore.

Some of your scores are sadly enough not available on record or CD, for example RAISE THE TITANIC, HAMMETT and HANOVER STREET.

If you look at that period of time, all those movies were done in the same period, the mid-seventies. It was a bad period for orchestral film music. The record companies were just not paying those kind of re-use fees for 80-piece orchestras. HAMMETT was a small orchestra, but RAISE THE TITANIC was a big orchestra and HANOVER STREET was done in England with a pretty large string orchestra.

Would you consider releasing them on disc yourself?

The company that did RAISE THE TITANIC no longer exists. HAMMETT I put together as an album. I really like that score, but it was done by Zoetrope, Coppola’s company. As for HANOVER STREET, I don’t think there would be a demand for the whole score.

Do you always conduct your own music?

Always, that’s all the fun of it. When you write, you write to specific timings, but when you finally get on the floor and you start to conduct and you have a 70-80 piece orchestra, certain things start to change, the orchestra breathes in a different way. Conducting your own music is so important. You can make all kinds of adjustments. I’m not talking about vast adjustments, but slight adjustments. You can move a moment a little forward or a little back. You have written the whole thing and feel that and know the picture backwards, you’re quick on your feet and do all those changes.

You wrote music for several commercials in the sixties.

I did. All the big directors were doing commercials in England. I did a commercial for toilet paper; Lester did one for Black Magic Chocolate. I learnt a lot in being given 30 seconds or one minute to make a statement. It really makes you tighten up. I found it a very interesting experience.

Can you tell us something about CRY, THE BELOVED COUNTRY?

Anant Singh, the producer, called me. It’s the first South-African movie since Apartheid ended and I knew the story, a terrifically powerful story. He came into New York and he said: “We don’t have a lot of money, but see if you like it. We can probably do some deal.” He brought the movie to New York and I saw it and I liked it very much. James Earl Jones was fantastic in it and so was Richard Harris. I said I would do it and I love very much what I have done for this movie.

The trailer has music by Enya. This song is not on the CD.

The song is at the end of the movie, but Enya’s company would not allow it to be on the CD.

In a few tracks you used a theme from ZULU.

It’s based on a Zulu hunting song. When I did ZULU, the director Cy Enfield brought back a lot of tapes with Zulu music and one of them is this chant (John Barry’s chanting) and then I did variations on that. So both these themes are based on a traditional Zulu hunting song, which is probably 200 years old.

Last question. What is the function of film music?

Oh, my God! It has different functions in different movies. I don’t think there is one overall function. You can have a movie like THE WISPERERS, which has a lot of dialogue and where the music is supportive or you can have a movie like OUT OF AFRICA where Sidney said, “You got to carry this movie. I have to step back and photograph these wonderful vistas and where the music has to carry the story.” With a lot of action movies today you cannot tell the difference between the sound effects and the music.